These Glowing Plants Could One Day Light Our Homes

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum gives us a glimpse into a world where we read by a natural greenish glow

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/1d/0d1d6adc-bb0a-4d42-ae77-5296fd1dce70/mit-glowing-plants.jpg)

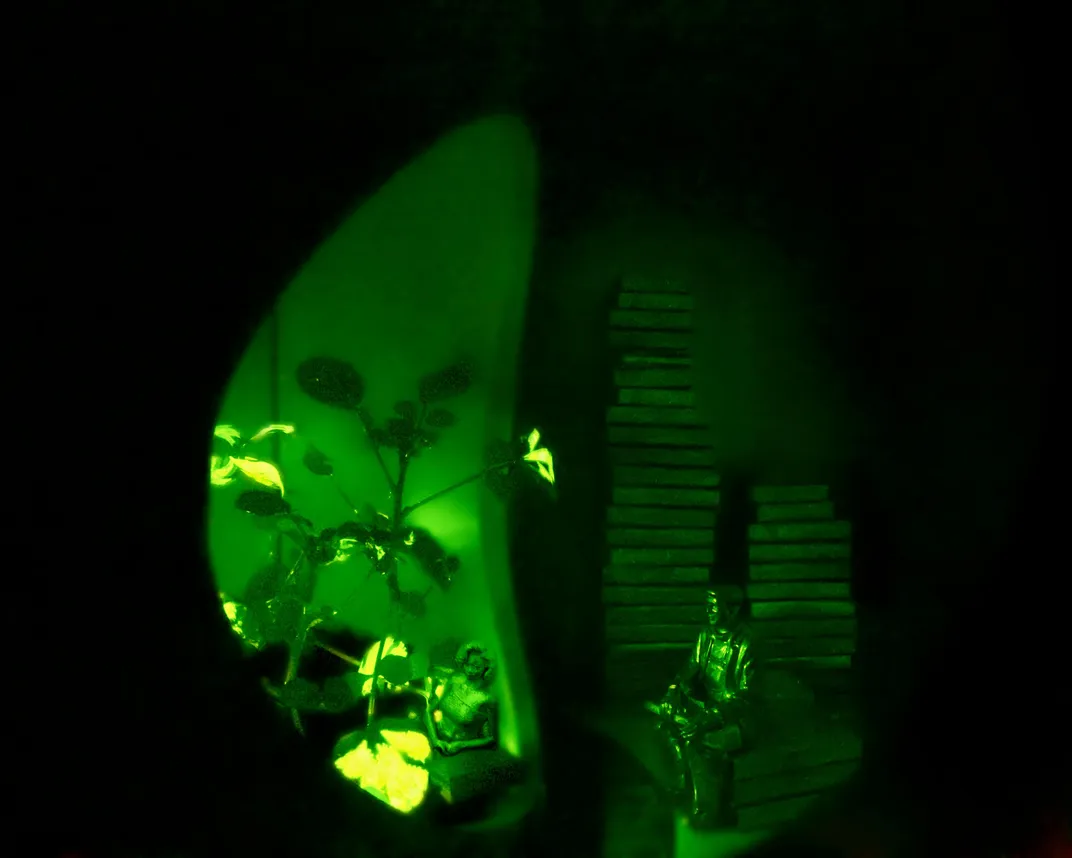

In the apartment in the brick tenement building, the people are having a party. They’re smiling and chatting with each other; they’re drinking cocktails and munching snacks. But the mood lighting is a bit strange. No candles or twinkly Christmas lights here. Instead, the light comes from enormous green-glowing plants in the center of the table.

What?

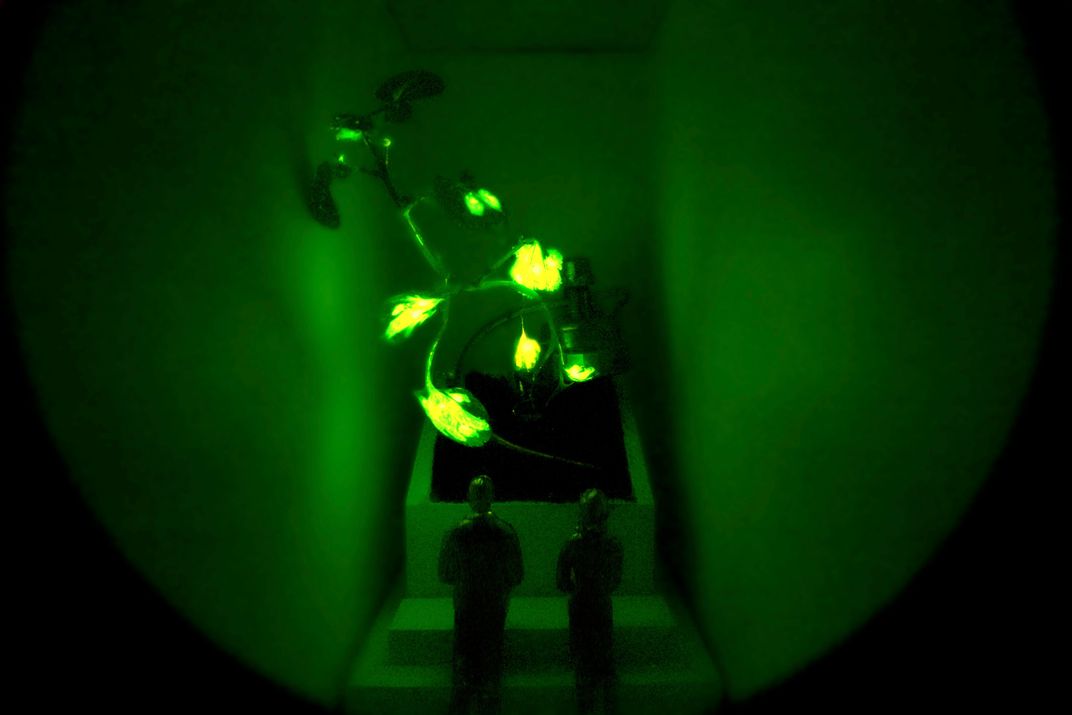

We should explain: This is a model, part of an exhibit inside the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. The “people” are small silver figurines. But the plants are real. They’re watercress embedded with nanoparticles that turn their stored energy into light. It’s a technology developed several years ago by MIT chemical engineer Michael Strano. Now, Strano has partnered with an architect, Sheila Kennedy, to explore how these plants might be part of our sustainable energy future.

The pair is one of 62 design teams involved in the Cooper Hewitt’s Design Triennial, which highlights innovative ways humans are engaging with nature. It runs through January 2020.

The plants in the exhibit are newer, brighter versions of the watercress plants Strano developed in 2017. Their glow is based on an enzyme called luciferase, which is what gives fireflies their light. Strano and his colleagues, who have applied for a patent, put luciferase and two molecules that allow it to work inside a nanoparticle carrier. They then immersed plants in a liquid solution containing the particles, and added high pressure. The pressure pushed the particles into the leaves through tiny pores.

In the exhibit, Kennedy and Strano envision a future world of limited resources, a world where sustainability is a priority. In this world, glowing plants might be not just a source of electricity, but a central part of our homes and lives.

“For the last two decades, plants have been a part of architecture, but they’ve always been relegated to being very obedient and conforming to the geometries and surfaces of architecture—green walls, green roofs,” Kennedy says. “We wanted to challenge that a little bit.”

The plants in Kennedy’s models don’t grow neatly in confined spaces. They fill entire rooms, their leaves and stems going wherever they choose. The rooms, which can be viewed through a peephole in the model tenement building, conform to the plants rather than the other way around. There’s an oval reading nook illuminated by a plant as high as its ceiling. There’s a shrine where two people pray in front of a plant many times larger than themselves. There’s the “party room,” where guests mingle beneath the leaves. There's even a mock "soil auction," an event for a world where dirt is like gold.

Visitors are encouraged to snap photos of the plants through the peephole and upload them to Instagram, tagging the MIT lab, @plantproperties. It’s a crowdsourced method of monitoring growth, as well as a way to get people excited about the idea.

Kennedy, who is a professor of architecture at MIT and principal at Kennedy and Violich Architecture, is known for her work with clean energy. For her, the project of bringing plants front-and-center in architecture was an interesting design challenge. She and her team had to figure out how to get enough light into an old-fashioned building, how to bring in sufficient water, and where to put and contain enormous amounts of soil. The resulting model rooms have modifications like lightwells cut in the ceilings, ports to allow in pollinating insects, and retaining walls to hold in dirt.

“We depend on plants for oxygen, for nutrition, for medicine,” Kennedy says. “We’re just adding one more dependency, which is light.”

Bringing living plants into a museum was its own design challenge. The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum houses fragile, light-sensitive paper and textile objects, so windows have UV-blocking film. But plants need UV light, so Kennedy and Strano’s team had to be extra-creative with their building design to get enough light in. The museum was also concerned about insects from the dirt, which could damage collections.

“It’s very challenging for a museum that traditionally shows design and decorative arts to show living objects,” says Caitlin Condell, a curator at the museum who worked on the Triennial. “But the designers were really eager to find a way to make that work.”

Kennedy and Strano’s team will periodically come down to Boston to check on the plants and swap them with new ones.

The nanobiotic plants are one of several exhibits in the Triennial that showcase organic energy; another piece is a lamp made of light-up bacteria. The dim glow of such inventions invites people to consider what living with electricity-free light might feel like.

“We come home every day and take for granted that we can turn on an electrical lamp and have the room fully illuminated as much as we want,” Condell says. “But if you are bound to nature for light, would you be willing to consider a different experience of illumination?”

The team is currently working on making the plants brighter and embedding light particles in larger plants such as trees. They’re also looking at adding what they call “capacitator particles” to the plants, which will store spikes in light generation and emit them slowly over time. This could extend the duration of a plant’s light from hours to days or weeks.

If humans depended on plants for light, perhaps we would nurture them better, Kennedy muses.

“If a plant dies for any reason—old age, neglect, whatever the reason may be, the light also dies,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)