These Letters Written by Famous Artists Reveal the Lost Intimacy of Putting Pen to Paper

Many of the letters included in a new book provide snapshots of especially poignant moments in the lives of American artists

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/0b/d10b0e9a-a463-459e-8968-5a4b888efc45/ahmotherwellsuppweb.jpg)

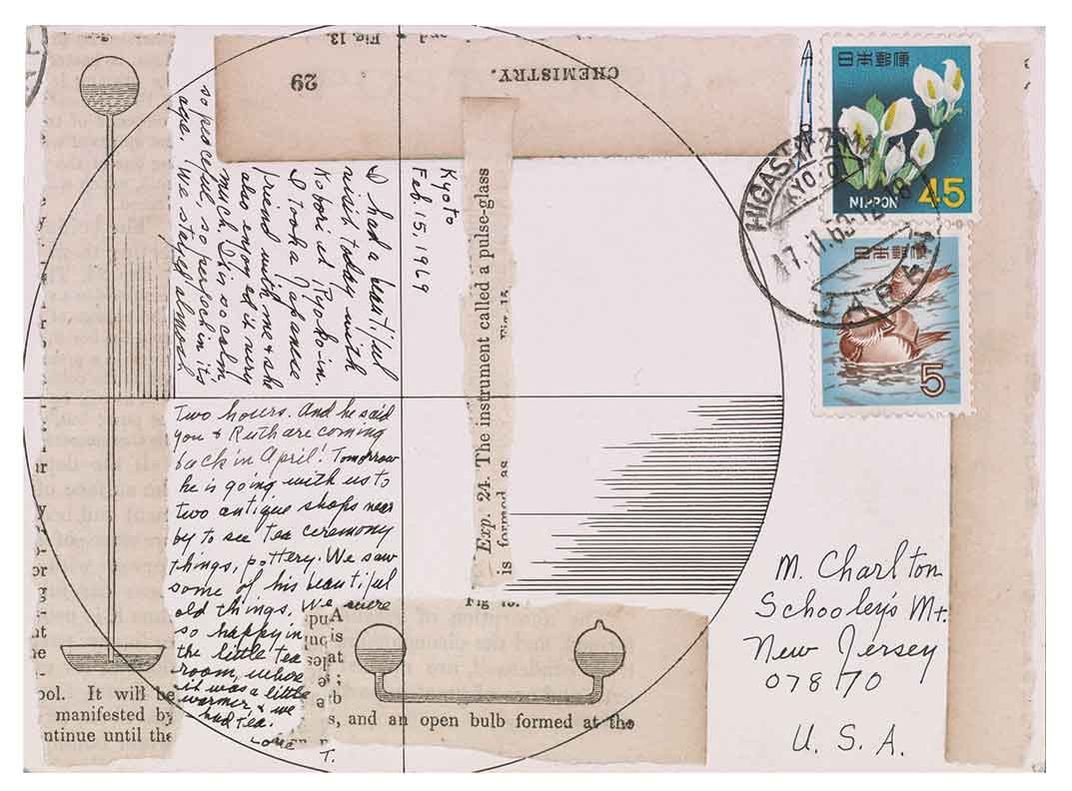

From time immemorial, handwritten correspondence has ranked among the most intimate and vibrant modes of human communication. To the letter writer, an unfilled folio is an empty receptacle, a vessel waiting to be infused with idle observations, snarky gossip, confessions of love, political speculations, soul-searching reflections, warm thanks, or whatever else might spring to mind.

Through the simple act of populating a page with words, punctuation, and images, the author of a letter, whether aware of it or not, manifests in the world a truly original, idiosyncratic expression of the self—a work of art. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, whose inventory is composed largely of artists’ handwritten messages and other ephemera of their lives.

These missives, which touch on topics as variegated as the personalities of their authors, served as the inspiration for the recently released book, Pen to Paper: Artists’ Handwritten Letters edited by curator of manuscripts Mary Savig.

Aiming to link word-strewn pages with paint-flecked canvas, and sculpted majuscule characters with sculpted metal statuary, Savig also reveals a distinctly human side to the giants of the American art world. One sees how the artistry latent within them permeated even the most seemingly banal facets of their lives.

The book owes its existence to the unmistakable handwriting of minimalist painter Ad Reinhardt, whose flowing, calligraphic phrases seamlessly blend emphatic lines and breezy arcs.

Savig recalls the moment when she and her colleagues, assembled for a staff meeting, realized that “almost everybody could identify Reinhardt’s handwritten words from across the room.” A lightbulb went off, one which would burn for the many months of deep exploration and engagement.

Karen Weiss, the Archives’ head of digital operations, was the first to suggest that adequately exploring the significance of artists’ individuated handwriting would require a concerted research effort. Savig began plumbing the depths of this country’s art community, seeking out students and scholars, curators and historians, professors and practitioners, up-and-comers and old hands alike, to weigh in on the writings of artists in whom they had personal interest.

One of Savig’s goals in crafting Pen to Paper was to remind readers that “art history is an active field, an interdisciplinary field, and there are many different ways of approaching American art.”

Allowing the book’s myriad of contributors leeway in their commentaries on the assembled letters was, from Savig’s perspective, essential: “I wanted to leave it up to them,” she recalls, “so they could show what they know about the subject, rather than trying to ask them to write specifically about something they might not feel as interested in speaking on.”

The results of this endeavor are striking. Every few pages of Pen to Paper, readers are presented with high-quality images of a new artist’s handwritten letters, and are treated to a fresh commenter’s pithy analysis, printed alongside.

These deconstructions range from the technically fastidious to the holistically biographical.

“The big curvaceous signature ‘Eero’ [Saarinen] resembles the boldly curved shapes in his Ingalls Rink at Yale, TWA terminal at JFK Airport, and Dulles Airport,” wrote architectural historian Jayne Merkel.

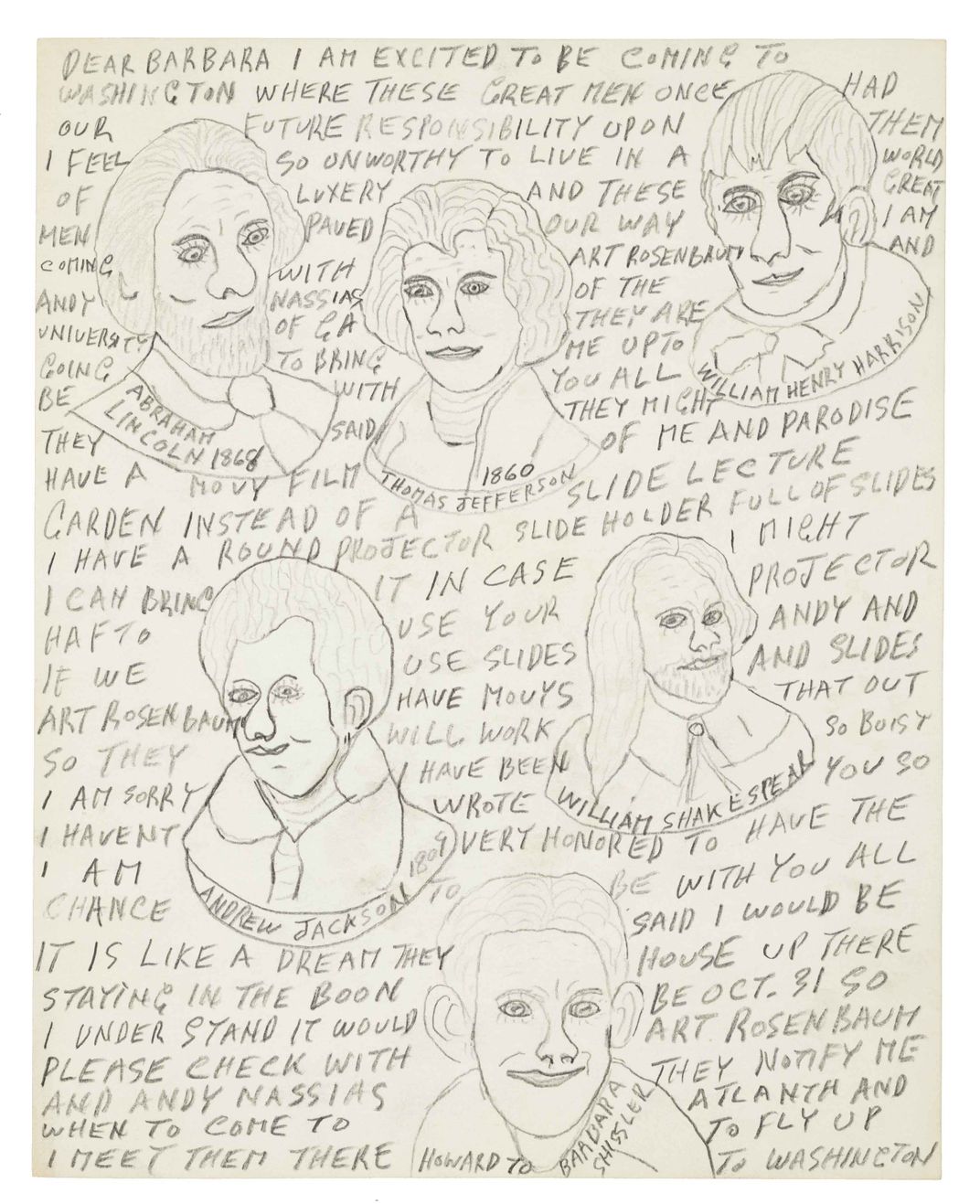

And for Leslie Umberger, the Smithsonian's curator of folk and self-taught art, legibility “falls increasingly by the wayside as [Grandma] Moses attempts to negotiate a demanding schedule, a high volume of family news, and a limited amount of space in which to write.”

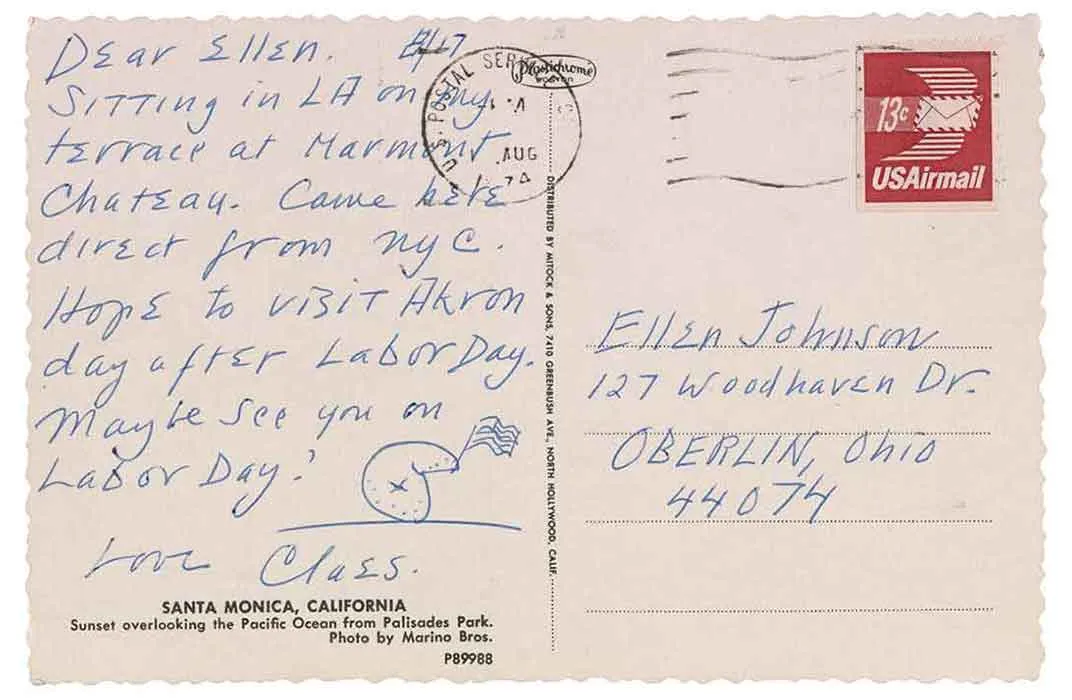

Many of the letters included in the compendium provide snapshots of especially poignant moments in their writers’ lives, highlighting for readers how a simple handwritten message can, in the words of Savig, “become this vestige of a person and a place.”

Take, for instance, Lee Krasner’s transatlantic Aerogram to longtime friend and lover Jackson Pollock, whose life would be lost in an auto accident shortly after he received her message. Knowing Pollock was struggling with emotional issues and alcohol, Krasner suffused her tidy letter with humor and cheer, at one point confiding in him that the painting in Paris “is unbelievably bad.” Confined by her medium, Krasner felt moved to end her note with a simple, heartfelt query, wedged in the lower right-hand corner and framed by a pair of outsized parentheses: “How are you Jackson?”

She would never receive a reply.

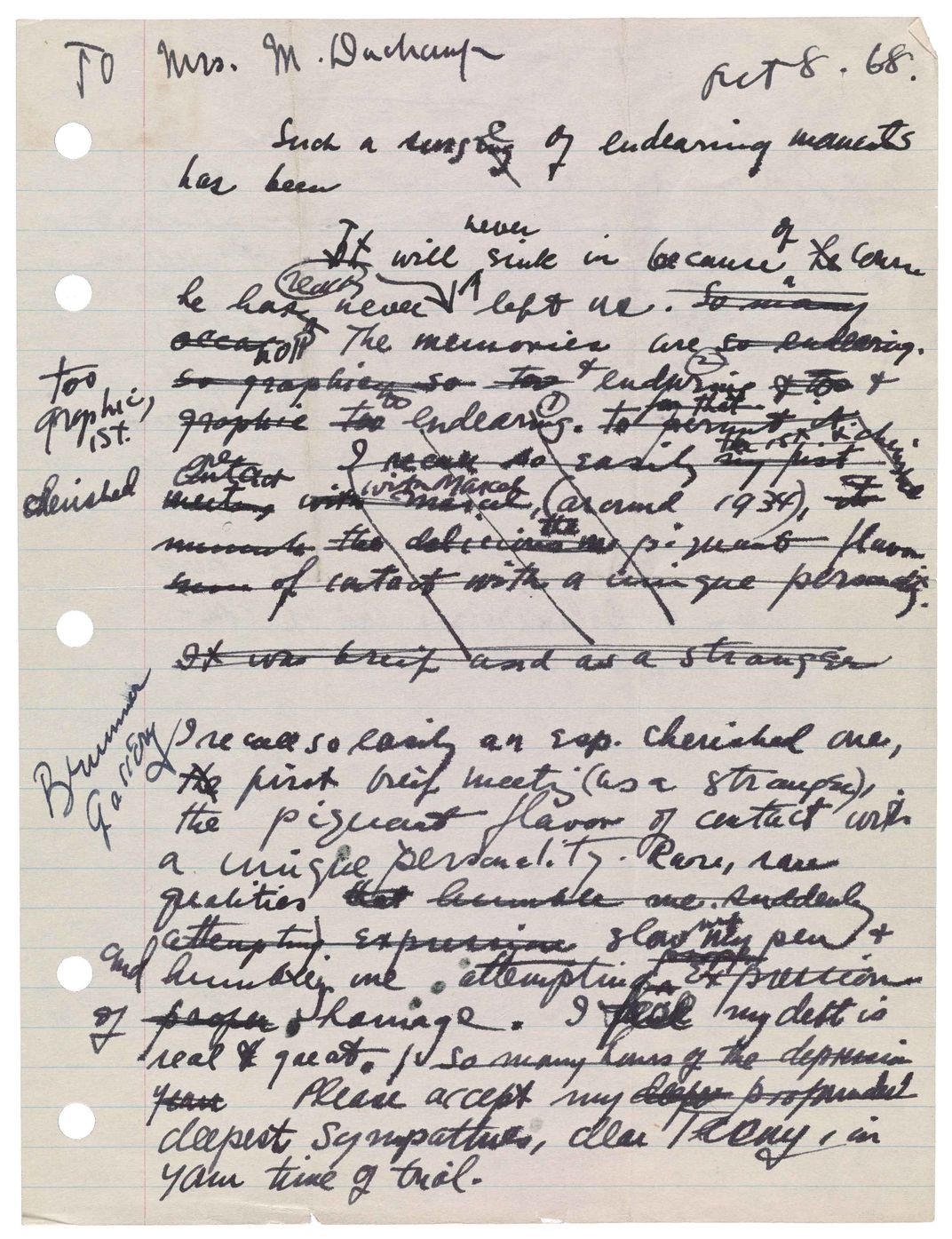

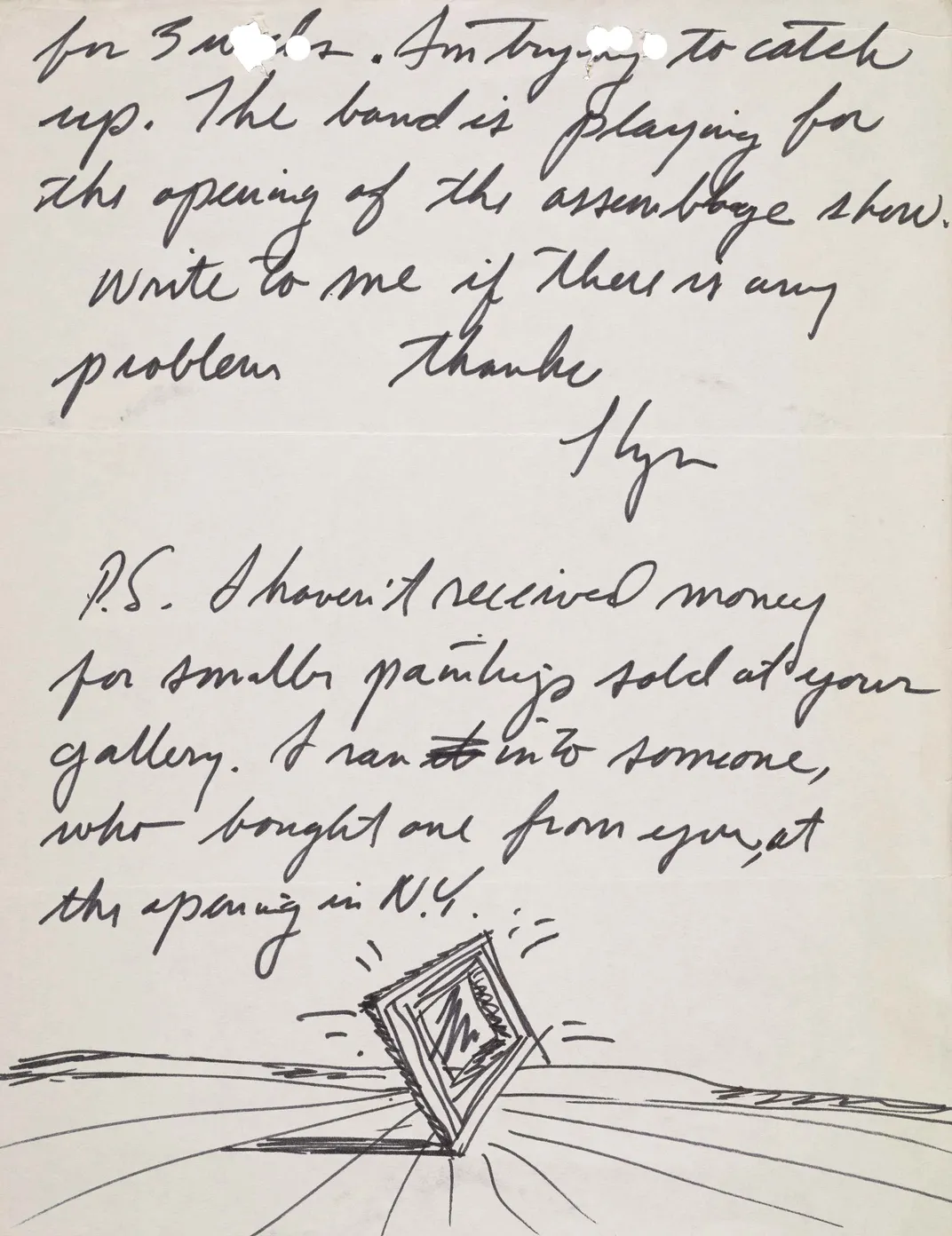

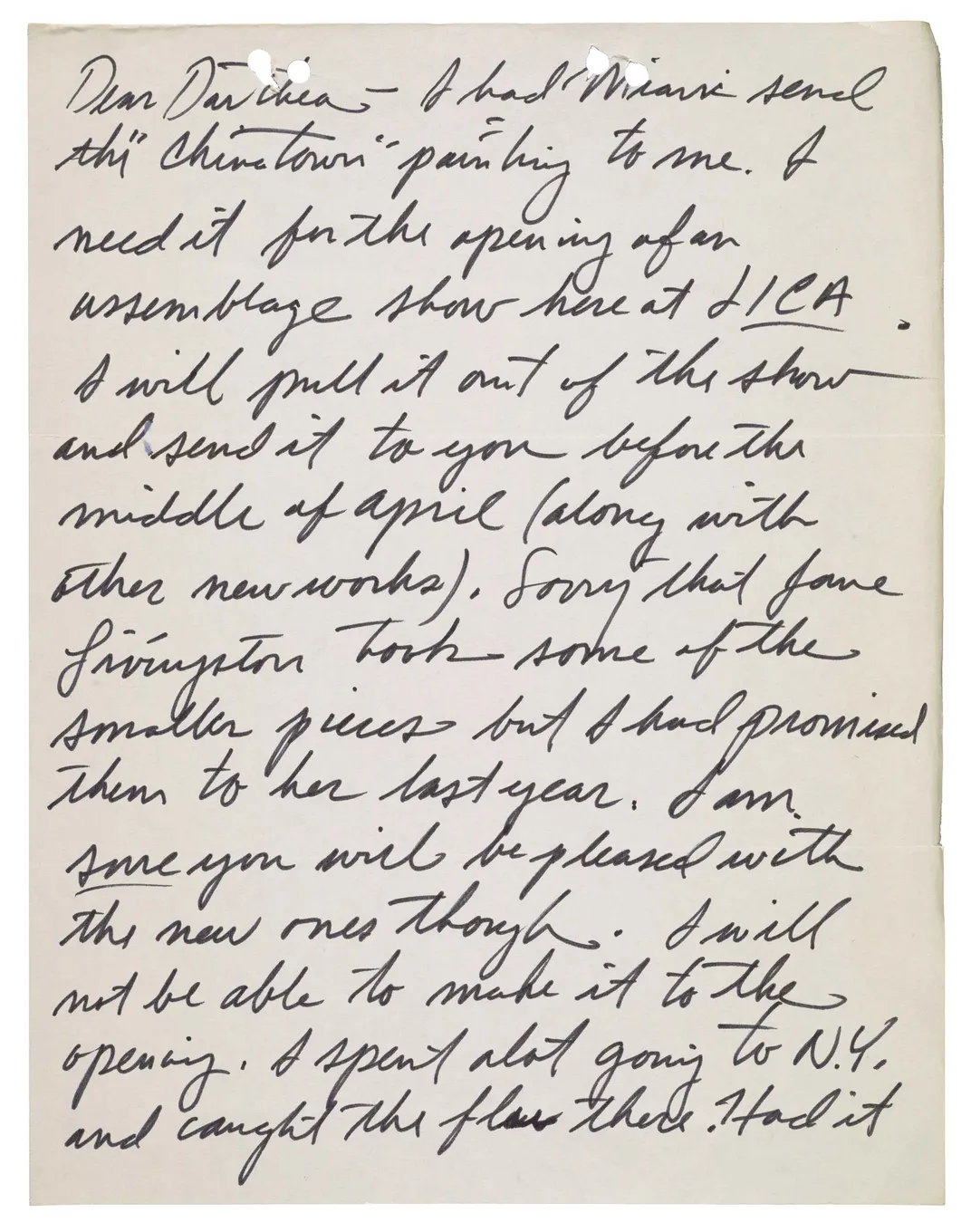

Similarly moving are the drafts of multimedia artist Joseph Cornell’s 1968 letter of condolence to the widow of his mentor and hero, Marcel Duchamp. Rife with ugly cross-outs and repeated attempts at rewording, the text on the page bespeaks the gravity of Cornell’s loss, the final and perhaps most damaging in a string of devastating deaths. “Receiving the news on Thursday, October 3,” curator Lynda Roscoe Hartigan says, “created a ‘turbulence’ that prevented [Cornell] from leaving his house until the following Wednesday, when he posted the condolence letter.”

Whereas some texts shed light on the tribulations of individual artists navigating their lives, other missives draw the reader’s attention to more wide-ranging, global struggles. For instance, in a 1922 note to an acquaintance at the Carnegie Institute, superstar impressionist Mary Cassatt attempts to come to terms with Edgar Degas’s assertion that “No woman has a right to draw like that,” a gibe elicited by Cassatt’s now instantly recognizable oil, Young Women Picking Fruit.

Unbowed, Cassatt succinctly rebuffed the Frenchman, employing a cursive script described by Williams College curator Nancy Mowll Mathews as “forceful”—the artist’s flagging vision notwithstanding.

“If [Young Women Picking Fruit] has stood the test of time & is well drawn,” Cassatt wrote, “its place in a Museum might show the present generation that we worked and learnt our profession, which isn’t a bad thing.” To this day, the pioneering American painter remains a role model for aspirant artists all across the globe—female and male alike.

In terms just as personal, African-American artist Jacob Lawrence used the epistolary medium to grapple with the specter of racist hatred in his homeland. Serving in the United States Coast Guard and stationed in St. Augustine, Florida, Lawrence was acutely attuned to the animus of those around him. “In the North,” he wrote in 1944, “one hears much of Democracy and the Four Freedoms, [but] down here you realize that there are a very small percentage of people who try to practice democracy.”

In an incisive interrogation of Lawrence’s handwriting, Boston University art history professor Patricia Hills calls attention to his blossoming capital I’s, which “appear to morph into his initials, JL.” Carving out a personal identity amidst the soul-effacing atmosphere of the Jim Crow era was a mighty challenge for Lawrence and his African-American contemporaries; their resoluteness in the face of incredible adversity is reflected in Lawrence’s confident yet occasionally faltering pen strokes, as well as in his eloquent words.

Including diverse perspectives such as those of Cassatt and Lawrence was, in the eyes of Savig, vital to the integrity of the Pen to Paper project. If issues of race, gender and sexuality were consequential enough for the profiled artists to wrestle with in their private correspondence, then, according to Savig, it was “important for a lot of the authors to touch on [them] too.”

In many respects, then, Pen to Paper stands as a testimony to the resilience of the artist’s creative spirit in a harsh and stifling world. In places, though, the reader is treated to expressions of unbridled elation—suggestions of a light at the end of the tunnel.

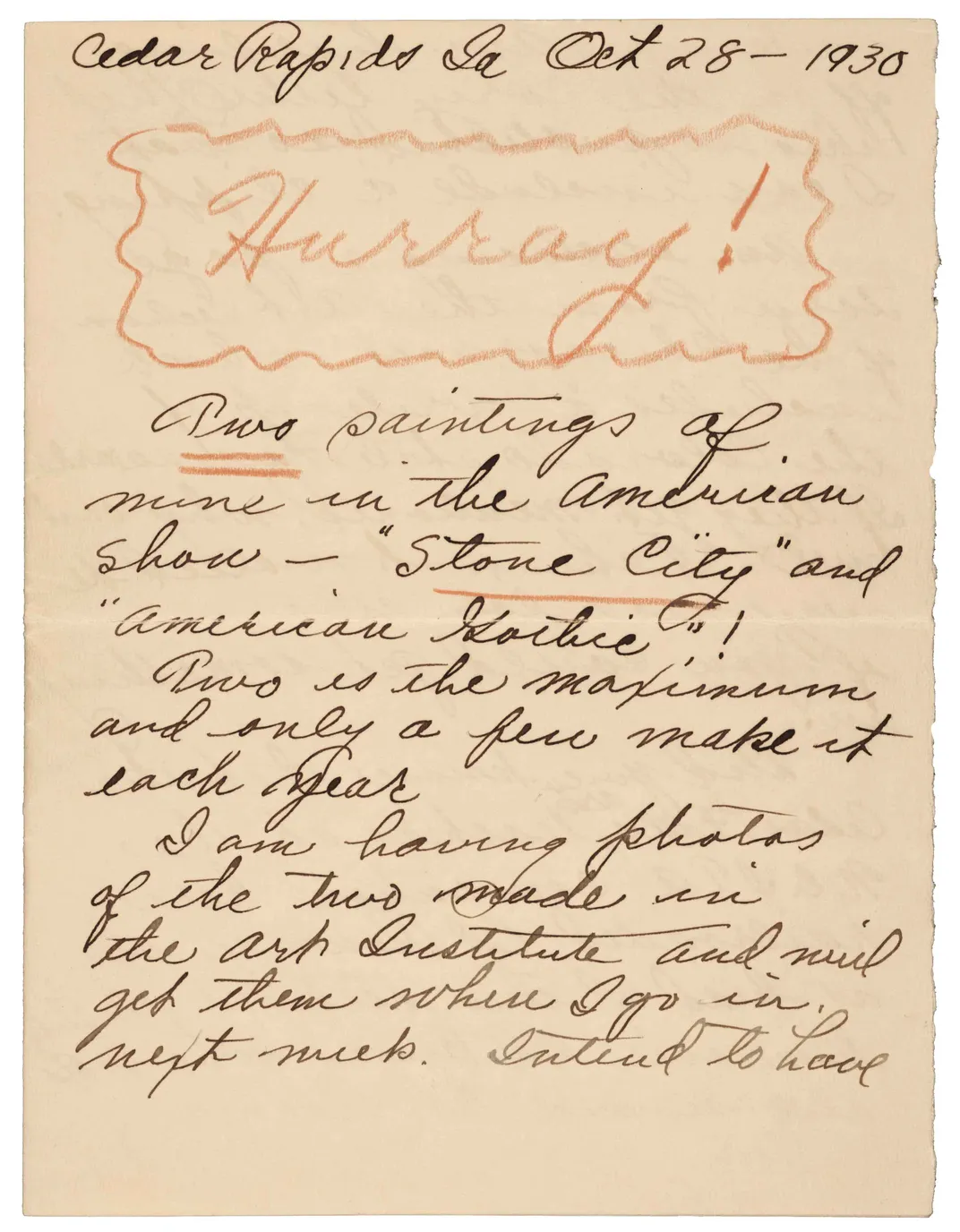

Take the very last letter in the collection, joyously scribbled by American Gothic creator Grant Wood, an unassuming Iowan who in 1930 found himself suddenly and irrevocably thrust into the national spotlight. Upon learning that two of his canvases, theretofore seen by no one outside his home state, would be given wall space at a prestigious Chicago Art Institute exhibition, Wood could scarcely contain his enthusiasm. As Stanford art expert Wanda M. Corn puts it, “Wood is so exuberant he forgoes a salutation. ‘Hurray!’ he exclaims in large red-pencil letters, surrounded by a hand-drawn frame.” Wood’s infectious glee complements perfectly the more somber tone of some of his coevals’ writings, providing a yin to their yang.

In sum, Pen to Paper, presented alphabetically, is an A-Z volume in every sense of the phrase. The book is a vibrant pastiche, an all-inclusive grab bag which reminds us that the artists under discussion are human beings too—“like People magazine!,” Savig gushes. At the end of the day, these great innovators are fundamentally just like us, and we, as equals, may feel free to draw on their examples in our own moments of need.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)