Some 50 congregants gathered by the windows of Vernon AME Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma, one of the largest of the city’s Black-run religious organizations. The image by an unidentified photographer was taken in 1919, just two years before the community would suffer the nation’s deadliest racial massacre, devastating the Black neighborhood of Greenwood and leaving businesses and homes destroyed and some 300 Black Americans brutally murdered. The historic image of the congregation’s members, many standing shoulder to shoulder, documents a vibrant community and an influential Black church, growing and thriving.

In another image, a Black nun, likely the Reverend Consuella York, known as the “Jail Preacher,” engages in pastoral care during a prison ministry visit in Cook County, Illinois, in the late 20th century. Her head is bent, and her fingers gently touch the neck of an imprisoned young man.

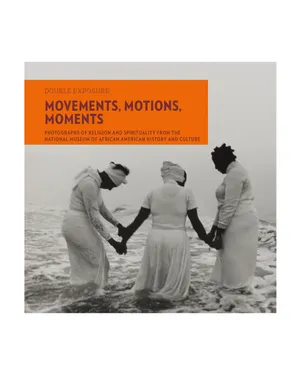

These evocative photographs are among 65 featured in Movements, Motions, Moments, a new volume of images and essays that depict and analyze the many facets of religion in Black life. The publication is rich with images of an attendant preparing wine for communion; a young female usher passing out cardboard fans to parishioners on a warm summer Sunday; baptisms, weddings, bar mitzvahs and funerals.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/ac/fbace71e-b3ca-436c-9d76-e72b6adf0f26/37_2014_75_40_001.jpg)

The new volume, out in January, marks the eighth installment of the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Double Exposure series, which for nearly a decade has showcased the museum’s photographic collections to the public. The series’ tiny but consequential volumes explore Black American life, with past collections featuring women’s impact, a spotlight on children and the courage and dignity of military service.

Movements, Motions, Moments offers a visual journey from the early 1870s to the present, depicting the story of how African Americans take action in sacred worship, ministry or ceremony according to their beliefs. Notable photographers featured in the book include Lola Flash, Kenneth Royster, James Van Der Zee, Milton Williams, Jason Miccolo Johnson, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Lloyd W. Yearwood and Chester Higgins.

The decision to delve into religion and spirituality for the eighth volume stemmed in part from the research and expertise of the museum’s curator of religion, Eric Lewis Williams. “Not only are photographers chroniclers of time and human experience, but the images they capture present to the world mirrors for self-examination, reflection and discovery,” Williams writes in the book’s lead essay.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a0/d7/a0d7e18b-620d-43c9-bd0f-706983822c49/48_2016_118_16_001.jpg)

Co-editors Michèle Gates Moresi and Laura Coyle, who immersed themselves in the museum’s collection for the project, emphasize religion’s role as a catalyst for change and a tool for empowering individuals, uplifting communities and even fighting systems that oppress African Americans, including racism and classism.

“We really wanted to convey the agency of African Americans through these stories, and we wanted to ensure that they meet our standards,” Gates Moresi says. “The photographs are compelling to look at, but the content is also rich to tell layered stories. We really want to ensure that we’re pulling people in and providing a message that they’re learning something new, and the Black experience is beautiful.”

Movements, Motions, Moments celebrates the diversity of spiritual practices among African Americans, from the Nation of Islam to the Church of God in Christ, Black Jews and Spiritualists. A Black rabbi of the Commandment Keepers who built an all-Black Jewish congregation in Harlem, New York, in the early 1900s is seen leading a Rosh Hashanah celebration. The minority ethnic group remains active on the East Coast and in the Midwest today. The editors were also intentional about centering a major group who are often excluded from the spiritual conversation: women.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5c/5d/5c5d5113-9c98-458d-98b0-c85dd101b101/71_2012_141_3_001.jpg)

To that end, the book’s cover features the photojournalist Chester Higgins’ powerful 1995 photograph Ancestral Memorial, Coney Island, a black-and-white image depicting women dressed in white, knee-deep in the waters of Coney Island Bay, intimately joining hands in prayer. They are perhaps praying for or acknowledging the Maafa, the Swahili word for “terrible occurrence” or “great tragedy” that is used to refer to the enslavement of Africans. The sacred ground where the women stand is a memorial site established by the People of the Sun Middle Passage Collective to commemorate the estimated two million enslaved Africans who did not survive the horrific conditions aboard the slave ships in their forced voyage known as the Middle Passage.

“What you’re looking at in that picture is an indication of a new space, a new spiritual space that had been opened,” says Higgins. “These three women made a universal, natural church a sacred moment. We’re all after a sacred moment.”

Along with showcasing diversity, the book’s editors emphasize respect for the emotion often felt during acts of Black religion and spirituality. Although considered a common theme among photographers, spirited responses remain powerful and impactful to those who witness them or view them in a camera frame. A photograph taken during a service at Carolina Baptist Church shows a woman standing among seated congregants with her hand outstretched and lifted, crying out. She is likely what many Black churchgoers would call “in the Spirit” or having the “Holy Ghost.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9b/5d/9b5d1121-58d0-482b-900c-8ff19ad3bfc7/35_2021_115_5_001.jpg)

The new volume also explores how worshipers exhibit flexibility in response to global circumstances. “Religion and spiritual practices are constantly changing,” says Coyle, “They are adaptable like the rest of the American public.”

“African Americans have become more secular in their beliefs, or they identify less frequently with a particular religion or community, but that doesn’t mean that they’ve given up religion or spirituality,” she adds. “They’re finding it in different ways.”

Perhaps what manifested adaptability in spirituality and religion most recently is the rise of Covid-19. The pandemic unfolded during the planning stages of the book, and the editorial team found themselves exploring its wide-reaching effects. Rather than complicate the project, it added even more depth.

No longer able to meet in person, the team compiled digital files of photos virtually, and they intentionally sought out photos that told the story of worship and spirituality during a pandemic, including how Black people had to adjust to find community when houses of worship were not available.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/e5/dee511d8-4142-4926-825a-a84c6bd1a8ba/36_2019_28_37_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/60/5260f7f3-7d83-4c1c-ab90-897d0db95cb2/36_2020_26_13_001.jpg)

The pandemic embedded itself into every area of our lives, including our sacred lives. A 2020 photo shows then-Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory, whom Pope Francis elevated to cardinal later that year, wearing a “Love Thy Neighbor” mask along with his regalia. Coyle suggests the safety protocol encapsulated the spirit of the pandemic at a very isolating time.

“He’s so decked out in the garments of power for the church, yet he’s boiling it down to this very basic message that is universal for almost all religions,” Coyle says. “Treat other people as you would treat yourself and to love thy neighbor. … How hard that can be, to remember to love your neighbors, when you can’t see them and be with them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/6e/786e3c0f-6e7b-4c8f-b8b2-df658388ae40/41_2021_31_65_001.jpg)

A common theme uncovered in the book is ministry and spirituality as forms of service to others. Black religion, politics and activism have always intersected and continue to do so. Movements, Motions, Moments reflects that activity through photos of Hiram Rhodes Revels, the nation’s first Black senator, who was also an African Methodist Episcopal Church minister. It also features the Reverend Henry Highland Garnet, whose ministry propelled him to become a speaker at the 1843 National Negro Convention and deliver the first sermon by a Black clergyman before the House of Representatives, in 1865.

The wide range of images tell the story of what’s often overlooked, according to Coyle. She describes religion as a “subversive force in the United States” that can “help a people that have been marginalized or oppressed deal with the hand they were dealt.”

“Activism and uplift are connected to religion in the Black community in a really powerful way,” Coyle says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/ae/6baef7ce-bcab-49ba-8bc0-95456a7702a5/57_2021_112_2_001.jpg)

Some photos’ subjects are familiar, she says, such as Martin Luther King Jr. But newer leaders are also featured, including Janaya Khan, co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto. Pictured leading a massive protest in Hollywood in 2020, Khan carries on the legacy of Black activism today by employing the tradition of sacred rhetoric.

“The book really tried to capture that range of photographs,” Coyle says.

The editors hope readers, even those who consider themselves familiar with the museum’s work, will gain new perspectives through this volume of Double Exposure.

“People may not be so aware, at least people outside the religious communities might not be so aware of how big of an impact that community can have on the people in the community in helping them understand their own humanity, when there are so many forces trying to take their humanity away,” Coyle adds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/81/9f/819fd34a-8447-4f37-829e-aa1947425625/67_2010_38_10.jpg)

Continual threats to that humanity lead to more communities forming to engage and find healing together. One such outgrowth is Harriet’s Apothecary, a multi-identity women’s group dedicated to Black bodies in motion. In one of only a handful of full-color photographs in the book, Neshima Vitale-Penniman captures a healing village session at a farm in New York. A facilitator guides members through an exercise as they sit on the lawn, positioned across from each other, touching hands to “pull back layers of injustices,” according to the description.

Gates Moresi says this volume can provide a different perspective for readers.

“We want them to think about the historical context, and the historical and cultural significance of what they’re looking at to be able to, perhaps, read a photograph, deeper than what you just saw,” she says. “Ultimately, what they get is that African American religious faith is just as multifaceted as America, and maybe they can see a little bit of themselves in the book.”

:focal(1500x1043:1501x1044)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8c/16/8c160cc8-141c-4222-a0e1-857d46b5b96f/80_2015_227_16_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_5575-edited.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_5575-edited.png)