These Rarely Seen Images Show Jazz Greats Pouring Out Their Hearts

Frank Wolff’s gritty portraits, the hallmark of Blue Note Records, became a visual catalog of jazz in action

In the jargon of jazz, a “blue note” is one that deviates from the expected–an improvisational twist, a tickle in the ear. It is fitting that Blue Note Records, founded in New York by German expat Alfred Lion back in 1939, took its name from this artifact of genre, for throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the institution was continually surprising (and delighting) its audience.

From boogie-woogie and bebop to solo stylings and the avant-garde, Lion’s label left no tone unturned. The undisputed quality of Blue Note’s output was the direct result of its creator’s willingness to meet the artists on their level, to embrace the quirks and curveballs that make jazz music what it is. As an early Blue Note brochure put it:

“Hot jazz… is expression and communication, a musical and social manifestation, and Blue Note Records are concerned with identifying its impulse, not its sensational and commercial adornments.”

Little wonder that such luminaries as John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, and Miles Davis were drawn into the fold: Blue Note treated its artists with the utmost respect and camaraderie, and pushed them to produce original, visceral jazz of the sort attainable only with time and hard work. The music that arose in this atmosphere was like no other.

Perhaps just as powerful as the recordings themselves, however, were the striking black-and-white rehearsal photographs captured by Lion’s childhood friend and fellow German national, Francis “Frank” Wolff—a selection of which, including images of jazz greats Art Blakey, John Coltrane and Ron Carter, is on view through July 1, 2016 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Wolff, after finagling an eleventh-hour escape from the Nazi regime in 1939, rejoined his confrere in the States, where Lion recruited the young photog and jazz enthusiast as his partner at Blue Note Records.

Initially, Wolff’s duties consisted primarily in managing the business side of the company, but by the time the late '40s rolled around, the shutterbug was actively snapping shots at the recording studio, which often took the form of a small Hackensack house owned by the parents of sound engineer Rudy van Gelder.

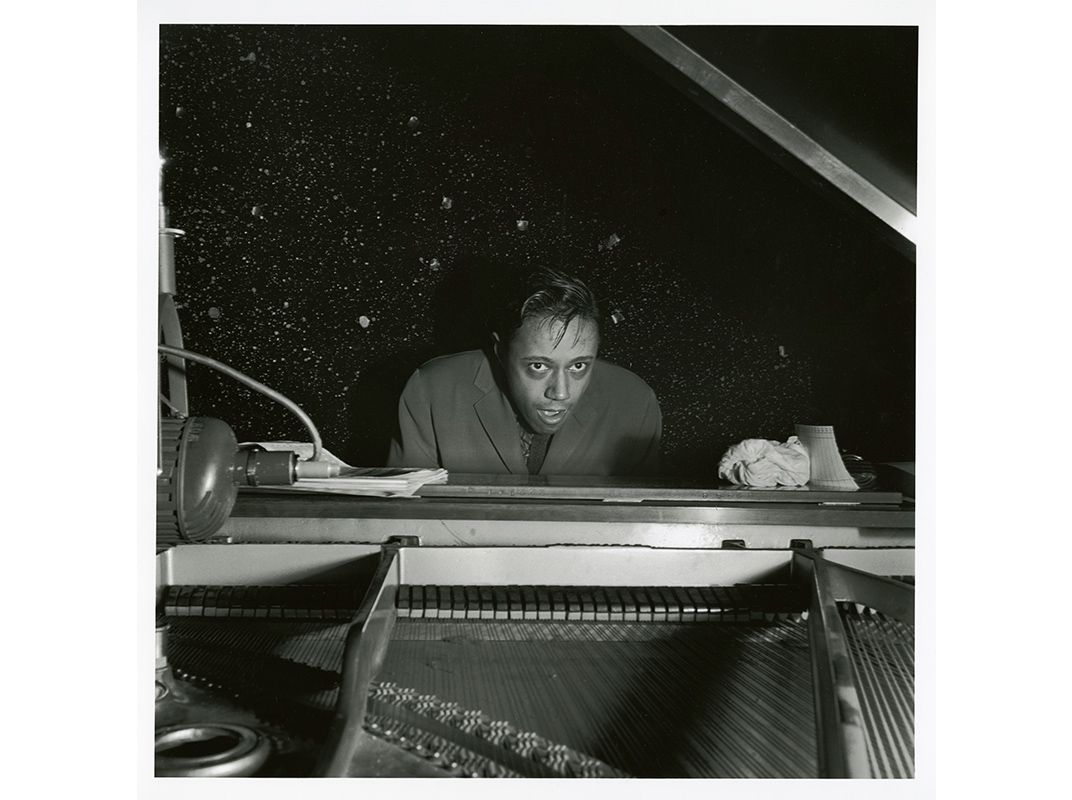

Wolff’s images are something to behold, largely by dint of the sheer expressive candor of the subjects they depict. As Herbie Hancock has noted, “You weren’t aware he was taking pictures—they were never posed shots.” We see in Wolff’s oeuvre tightly closed eyes, sweat-smothered brows and taut muscles; cracked, wrinkled fingers dancing over faithful, time-scarred instruments; smoke rising sensually above gleaming brass trumpets; heads bowed in devotion.

We also perceive contrast of the starkest sort. Indeed, the illuminated artists in Wolff’s work are frequently set against pitch-black, cosmic backgrounds, an effect achievable through shrewd employment of an off-camera flash. In individual portraits of this nature, we see lone musicians pouring their hearts into the void. In other images, the light is evenly shared among collaborators whose aim is mutual betterment. In this way, Wolff gets at the fundamental yin-yang of jazz: the solo vs. the shared melody, the shine of personal achievement vs. the warmth of symbiotic feedback.

Wolff’s visual catalog of jazz in action was far from incidental to the success of Blue Note’s brand. With the advent of the 12-inch long-playing record, his images found a perfect home: album sleeves, which were suddenly large enough to accommodate ambitious, eye-catching designs.

His gritty portraiture rapidly became a hallmark of the Blue Note aesthetic, as did the typographical and formatting flourishes of graphic designer Reid Miles. In Wolff’s own words, “We established a style, including recordings, pressings and covers. The details made the difference.”

Beyond the fact that his photographs were featured on iconic album covers, it is the sheer size of Wolff’s body of work—comprising thousands of images captured over the span of two decades—that cements its status as a groundbreaking cultural inventory. Curiously, had Blue Note not gone out of its way to pay its artists for rehearsal time (a truly innovative concept), Wolff’s prolificness would likely have been much diminished, since the noise of a snapping camera was generally unwelcome in the context of a bona fide recording session.

David Haberstich, curator of photography at the National Museum of American History, highlighted the above point when interviewed, stressing that, by virtue of the largesse of Alfred Lion’s label, musicians were often afforded three or more rehearsals before each recording session—giving Francis Wolff precious opportunities in which to, as Haberstich put it, “click away.”

In sum, it was the artistically vibrant climate engendered by Blue Note Records that precipitated both the masterpiece albums and vital jazz photographs we are so fortunate to have access to today. Blue Note classics are liable to be found in any record store imaginable, but the rare opportunity to view Francis Wolff’s compelling images lasts but a few months at the Smithsonian.

“The Blue Note Photographs of Francis Wolff” is on view through July 2, 2016 at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Enjoy other events and happenings as the museum celebrates Jazz Appreciation Month.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/e8/54e8c18f-cf93-40c5-a9a5-e99fe9d7050c/ac1238-0000025-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/00/d600d790-5679-4bf5-a942-a78e1a3de796/ac1238-0000023-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/6f/6c6f32dd-c1e9-4f76-8e43-5950645a0918/ac1238-0000017-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/87/a1870a25-7267-43ad-9d7d-c0be7515d8b2/ac1238-0000006-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/08/c708aebf-8a8c-4043-9584-3d5e2e2724d6/ac1238-0000003-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/99/3e99ef66-778e-4255-b748-48b93c97d32f/ac1238-0000001-web-resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/d4/23d42686-ed84-4866-808b-9f70840589b0/ac1238-0000011resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/5f/9f5f79a2-4ef4-4d92-8ff2-bcd0bd5ab686/ac1238-0000007resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/7f/147f9b31-9ddb-4467-a074-465df44d35b7/ac1238-0000008resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/49/a749794c-115c-4373-bf4f-b9e7f7b2ba3e/ac1238-0000022resize.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)