These Two Scientists Turned Data From the Sun Into a Work of Art

After collecting real-time data from the sun, two astrophysicists got to tinkering with video game components and the outcome is breathtaking

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/e1/94e19bc0-32b9-4911-b440-494a5545263f/dsc3967web.jpg)

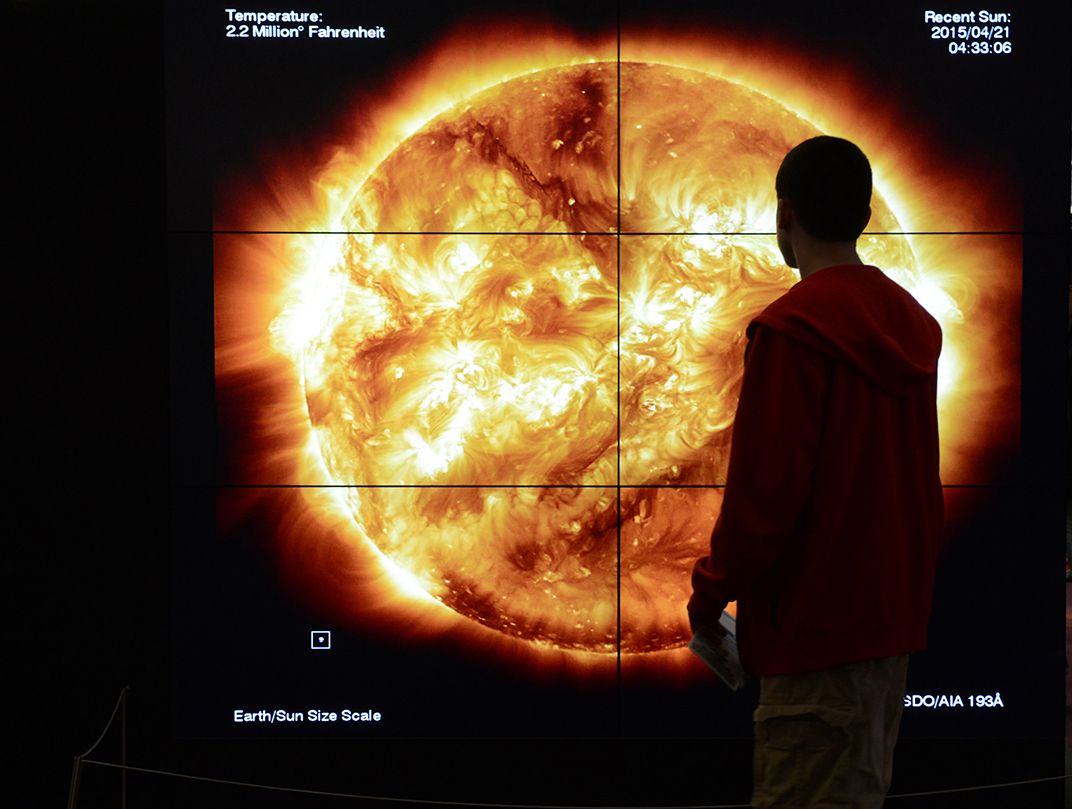

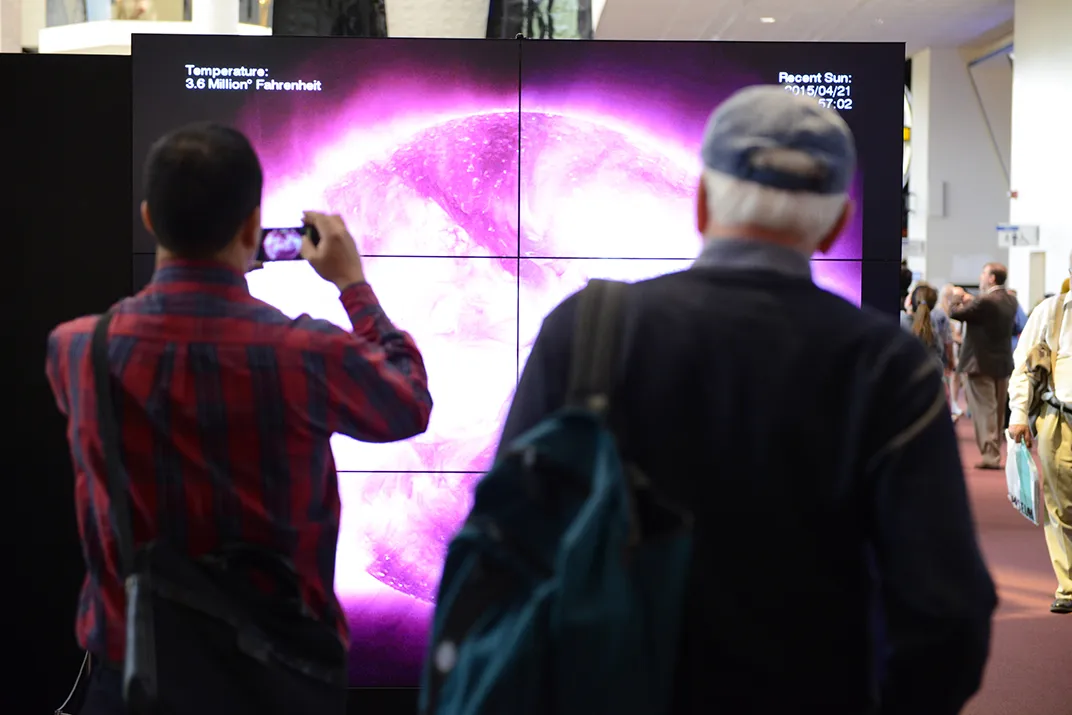

The sun is life-giving, powerful, distant and a bit of an unknown to most of us. But now the ethereal beauty —and the potent fury—of our solar system’s largest star can be experienced closely, in super-high definition and eye-popping color, thanks to a video installation that is part science lesson and part performance art.

The 7-by-6-foot video wall at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum closes the 93 million mile gap between the Earth and the Sun. The display resolution, at 4,096 by 4,096 pixels, is more than double that of the typical high-definition TV. The video, shown in loops, is an amalgamation of an astonishing amount of real-time data; viewers of the “Dynamic Sun” installation get to witness coronal loops, sunspots, solar flares and other solar activities within 24 hours of their occurrence.

The technological feat is the brainchild of two Smithsonian astrophysicists who decided that there was no reason that science couldn’t also be artful.

“I think it’s engaging even if you don’t understand what you’re seeing,” says Henry “Trae” Winter III — the lead architect of the project—of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. When someone takes in the display, “it transcends knowledge and really hits at the human experience,” he says.

“A visual like this is always good for getting that sense of wonder out of people,” says Winter’s colleague and co-architect Mark Weber.

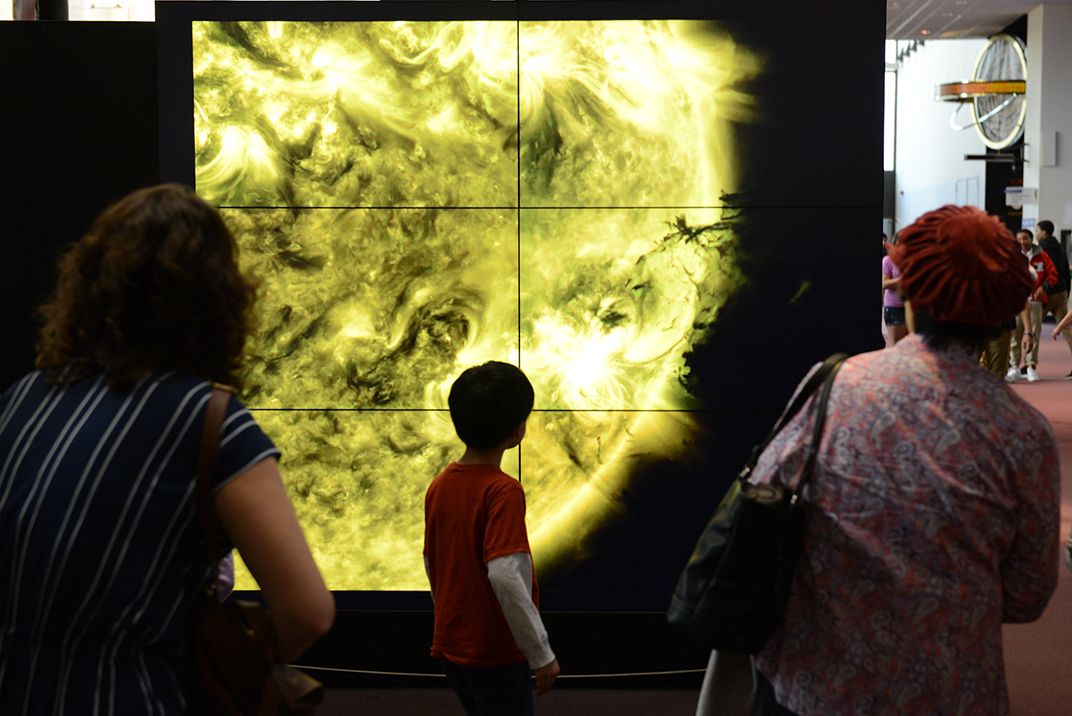

But he also wants them to see the ever-changing and dynamic aspects of the Sun. “Visually, people have a very flat view of the Sun,” Weber says. The goal is to have them “replace that picture in their mind and understand that there’s this whole other aspect of the sun that’s beautiful and complicated.”

He and Winter want to spread that gospel and reach as many people as possible. The video wall at the Air and Space Museum will be on display through 2019, they are building another to be delivered in 2018 for the opening of the rebuilt Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and they are lining up funding for a wall at the Cambridge Public Library in Massachusetts.

Taking a card from video gamers

Winter has always been a tinkerer. When budgets have gotten tight—as they tend to do—Winter has made do with what he could scrounge and scrape together.

The advent of the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) presented a new set of challenges. The AIA—built jointly by Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Technology Center and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory—is a powerful set of four parallel telescopes that are capable of taking photos of the sun every 10 seconds, on 10 different channels.

The device was mounted onto NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory, an orbiter launched in 2010.

The Observatory is a feat itself. It is in an orbit—called geosynchronous, some 22,000 miles above the Earth—that allows continuous observation of the Sun and simultaneous continuous download of its data. The goal is to give scientists more information on the Sun’s influence on the Earth and the AIA’s images are giving them a huge window into the Sun’s lifecycle and its idiosyncrasies. It’s also the fullest picture ever.

Unlike past missions, which only gave partial views of the Sun, “You get to see all of the Sun all of the time,” Weber says.

The Smithsonian astrophysicists needed to make sense of that huge picture; the AIA spits out some two terabytes of data a day, says Weber. It also has to be integrated with observations from other solar satellites, and, as per NASA’s charter, shared with scientists around the world. They decided to create a command console for use at the Smithsonian Astrophysics Observatory: the first video wall.

There wasn’t any official money to do that, so Winter built it himself using the tools available to the average gamer. “I could buy these video cards for hundreds of dollars and do the jobs of a ten-thousand-dollar computer,” says Winter.

“The cards have become so powerful and inexpensive that I can run a huge number of streams that are synched together perfectly,” he says. The finished product was “one beautiful canvas.”

It also caught the eye of a visiting Smithsonian official who noted that it would be great to have one installed at one of the Institution’s flagship museums on the National Mall in Washington.

This time, there was a small amount of money—$200,000 from Smithsonian and NASA grants—but Winter and Weber still had to cobble together time and resources to make the Air and Space Museum video wall a reality.

A lot of effort has also gone into figuring out how to compress the data into movie files and move those files around the world without crashing a server, says Weber. He and Winter, along with some colleagues, developed software that made it possible to transmit the movies and to automate the entire process. Still, it takes almost 12 hours to download a single movie (which contains multiple video loops) to the Air and Space Museum servers each day. It’s always done overnight to avoid any daytime crashes.

The movie is the endpoint of a multi-step process that starts with the data gathered by the AIA. The telescope sends isolated data parcels continuously to a lab in White Sands, New Mexico. That lab then sends discrete packets to Stanford, where they are reassembled into an image format. Stanford automatically archives the images and gives them to researchers upon request. Since there is so much data, there are multiple server hubs around the world—and the Smithsonian Observatory is a crucial hub for sharing the data with colleagues. Winter and Weber also directly tap the river of data to assemble the daily movies.

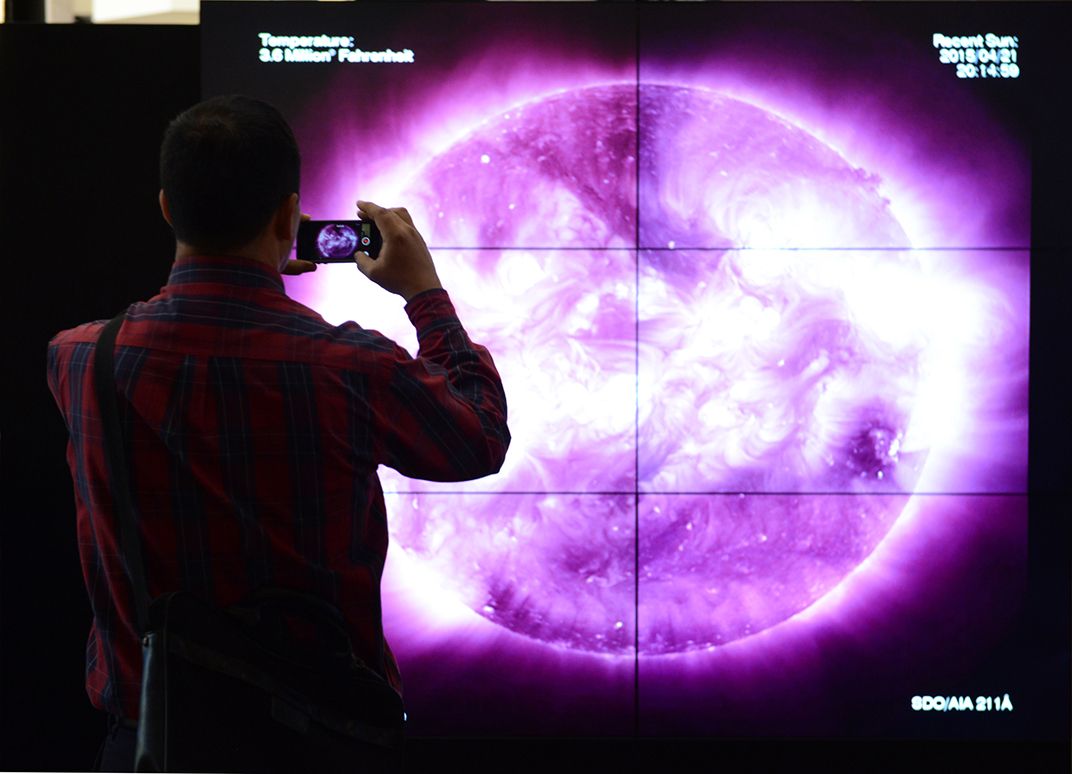

Winter and Weber share the data with their partners around the globe, and they also begin assembling the movies for the Air and Space Museum video wall. That involves “colorizing” the images — adding red, yellow, purple or green to represent different temperatures.

The Sun is a huge ball of gas, but it can be many different temperatures at the same time, ranging from 10,000–27 million degrees Fahrenheit. The AIA captures the wavelengths that correspond with those temperatures, but there are no colors associated with them. So, scientists add color as a key to aid in their research and understanding.

The colors also happen to make for some pretty intense visuals. As the video moves through the temperatures, it creates a kaleidoscope of shifting colors.

But, says Weber, “Just because the color is arbitrary, doesn’t mean the image is arbitrary.” He doesn’t want viewers to think they are only computer-generated graphics; they are the real deal with color added for interest.

The two scientists also have added a true-to-scale representation of the Earth; the Sun’s diameter is 109 times the Earth’s, which means something like one million Earths could fit inside the Sun.

It’s stunning because the Earth is just a tiny speck in the bottom corner of the video. “You understand a little better our place in the universe,” says Winter.

An artistic endeavor

And that is the nature of art—to cause us to question our experience, wonder about our humanity and inspire us to know more.

Winter is being increasingly asked to comment on Dynamic Sun as a work of art. In April, he participated in a Harvard seminar, “Art, Technology, Psyche,” giving a talk entitled, “Big Data to Big Art.”

“I’ve started wearing a beret,” he says half-jokingly, because he does consider himself an artist. The passion and creativity between art and science are shared, he says, adding, “Science is actually beautiful.”

The Dynamic Sun video wall is unquestionably art, says Matilda McQuaid, a curator at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. She and a co-curator basically stumbled on the video wall when they were looking for things to put in an exhibit to reopen the Cooper Hewitt after a three-year renovation. They were seeking out pieces from the Smithsonian’s collection and were intrigued with the Astrophysics Observatory. On a visit to the Observatory, they saw Winter and Weber’s in-house video wall.

It was “the most beautiful piece we’d seen in a long time,” says McQuaid. The Cooper Hewitt commissioned Winter and Weber to make a new video wall, and told them that “Dynamic Sun” would be the centerpiece of the “Tools: Extending Our Reach” exhibit, which opened in December 2014.

The 7-by-6-foot installation was placed next to a piece called “Controller of the Universe” which featured an assemblage of hand tools that gave the museumgoer the sense of being the master of their domain. But, turning around, they saw the tiny Earth next to the huge Sun. “You understand that we are not controller of the universe,” McQuaid says. “It’s very humbling—how small we are.”

The visual appeal of the wall (the exhibition is now closed) was “instantaneous,” she says. It was not as readily apparent as to why it was considered a tool; there was little explanatory text. But the text did tell visitors that the data that went into the videos was a tool to help astrophysicists link changes on the Sun to events on Earth.

Many people don’t understand that linkage, says David DeVorkin, a co-investigator on Dynamic Sun who is also a curator at the Air and Space Museum. “When the Sun burps or hiccups, the Earth catches a cold,” he says.

In 1859, for instance, a flare observed by British astronomer Richard Carrington led to a huge magnetic pulse that destroyed telegraph systems and created colorful auroras all over the planet. There have been other flares since, knocking out telephone service and electric power plants.

This type of link to the Dynamic Sun exhibition—and the back story on how it was developed—has not been made at the Air and Space Museum, but will be, eventually.

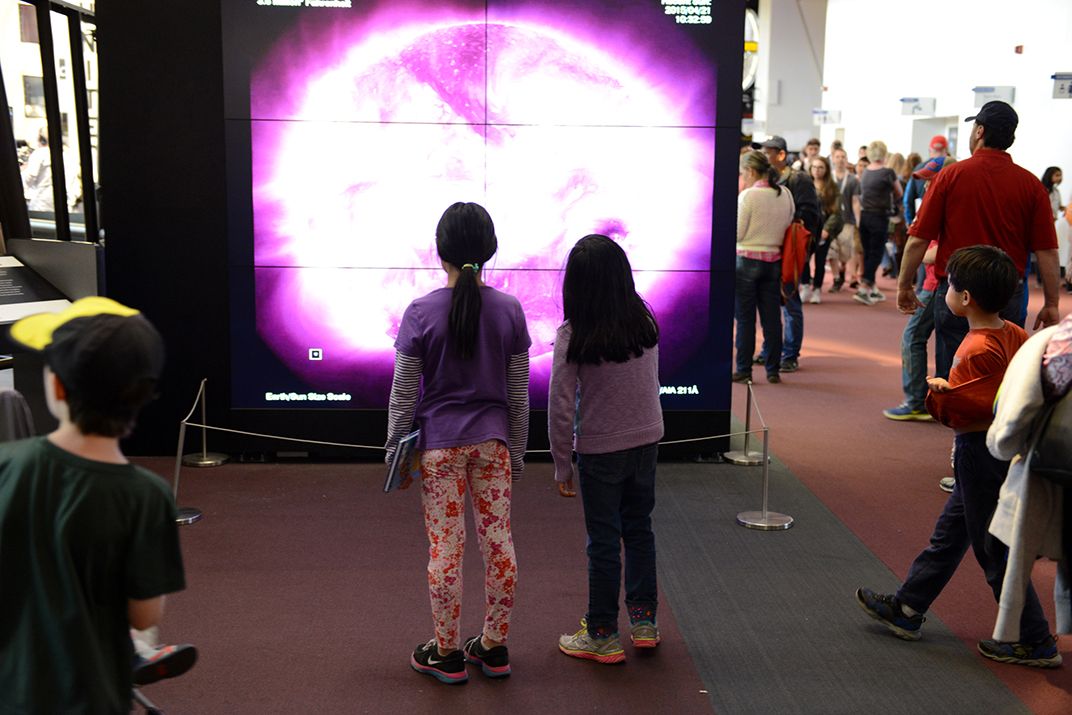

Even without the educational component, visitors are entranced. The Museum is normally chaotic with a lot of energetic children. The most someone spends on any particular item is 30 seconds, says DeVorkin. But with the Dynamic Sun, “the linger time is longer than what we normally see—it goes up sometimes to a few minutes.”

That’s exciting to Weber and Winter. For Weber, it’s all about finding ways to engage people in science. Having Dynamic Sun at the Air and Space Museum will hugely boost that engagement. “So many eyeballs are going to see it,” he says.

Winter says that Dynamic Sun “has been a passion project,” adding, “I definitely didn’t do it for the mad video-wall-money out there.” Having it displayed at Air and Space, which he calls “one of the most awe-inspiring places on the planet,” is, he says, “the achievement of a lifetime.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)