Following the tragedies that took place on September 11, 2001, curators at the Smithsonian Institution recognized the urgency of documenting this unprecedented moment in American history. After Congress designated the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History as the official repository for all related objects, photographs and documents, staff focused their attention on three areas: the attacks themselves, first responders and recovery efforts. As time passed, curators expanded their purview to include the nation’s response to the tragedy, recording 9/11’s reverberations across the country.

“This effectively put a net over the story, covering what happened on that day, then plus one month, plus one year,” says Cedric Yeh, curator of the museum’s National September 11 Collection. “But [this net] had a lot of holes. I don’t mean holes in the curators’ work, but [rather], there were areas not covered because it was impossible to cover the entirety of the story.”

Twenty years later, as the first generation with no firsthand memories of 9/11 comes of age, the American History Museum is adopting a new approach, shifting away from preserving what happened on that day to discussing the events’ long-term effects on the nation. “This is the time to start looking to create more context, to look more broadly, to be more inclusive,” says Yeh. “We want our audience to tell us what 9/11 means to them, not necessarily just for remembrance’s sake, but also to hear some of these stories that have not been heard.” (Learn more about how the Smithsonian is commemorating the 20th anniversary of 9/11 here.)

Today, hundreds of objects linked to the attacks, from office supplies recovered at the World Trade Center to firefighters’ gear used at the Pentagon to fragments pulled from the crash site of Flight 93, reside in the national collection. “After two decades, we continue to feel the lasting and complex personal, national, and global ramifications of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001,” says the museum’s director, Anthea M. Hartig, in a statement. She adds that the museum is committed “to keeping the memory of that day alive by working with a wide range of communities to actively expand the stories of Americans in a post-September 11 world.”

Below, read about 31 Smithsonian artifacts (listed in bold) that help unravel the complex story of 9/11 and its aftermath.

Maria Cecilia Benavente’s sandals

Ahead of the first anniversary of 9/11, associate curator David Shayt offered Smithsonian magazine a preview of the museum exhibition “September 11: Bearing Witness to History.” Most of the 50 or so artifacts on display, he said, were “perfectly ordinary, everyday objects we might otherwise not collect, except for the extraordinary nature of their context.”

Among these items was a pair of backless sandals owned by Maria Cecilia Benavente, who worked at Aon Risk Services, Inc., located on the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center’s South Tower. When American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower at 8:46 a.m., Benavente evacuated quickly, winding her way down 25 flights of stairs to an express elevator on the 78th floor. As she descended, she found herself slowed by her shoes—sandals with two-inch heels. Removing them, Benavente made the rest of the journey barefoot, clutching her discarded sandals closely until she reached a co-worker’s parents’ home more than 15 miles away in Queens. There, she received a replacement pair of flip-flops.

A second hijacked plane—United Airlines Flight 175—crashed into the South Tower at 9:03 a.m., trapping everyone above the 78th floor. Fifty-six minutes later, the building collapsed, killing almost 180 of Benavente’s co-workers.

By September 2002, Benavente had relocated from New York to Chicago. Haunted by memories of 9/11, she replaced the long skirts and fashionable sandals she’d previously sported with pants and practical footwear that could, as she told Smithsonian, “take her places rapidly.”

Window washer Jan Demczur’s squeegee handle

On 9/11, this unassuming squeegee tool saved the lives of six men. As Smithsonian recounted in July 2002, window washer Jan Demczur and five others were riding an elevator in the World Trade Center’s North Tower when their ride suddenly started careening down. Pressing the emergency stop button, the men managed to halt the elevator’s plunge at the building’s 50th floor. Upon opening the compartment’s doors, however, they found their escape route blocked by a thick wall of Sheetrock.

The only sharp object at hand was Demczur’s squeegee blade. Taking turns, the men scraped away at the drywall, slowly carving an exit. “We just started working,” Demczur told Smithsonian. “Focused on this way to get out. We knew we had only one chance.” Then, disaster struck: Demczur dropped the blade down the elevator shift, leaving the group with only the squeegee handle. But the men persevered, using the small metal tool to continue pushing through the Sheetrock. They emerged in a men’s bathroom and raced down the tower’s stairs, escaping the building just a few minutes before it collapsed.

After the attacks, Shayt decided to track down Demczur:

I called Jan in December—after some difficulties, I found him in Jersey City—met with him and asked him the big question: Did you hang onto the handle, do you still have that squeegee handle? He left the room and came back with something wrapped in a red handkerchief. Turned out to be the handle. He had kept the handle without realizing it. In his blind escape, he had somehow stuffed it in his pocket rather than put it in the bucket that he dropped later. His wife found it, rolled up in his dirty uniform, weeks later.

Demczur donated both the handle and the debris-covered outfit he’d worn in the elevator to the Smithsonian.

Bill Biggart’s photographs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/ed/cfedc62f-b07a-4be5-913b-b4a98f1d725e/screen_shot_2021-09-02_at_112932_am.png)

Bill Biggart, a 54-year-old freelance photojournalist, was walking his dogs with his wife, Wendy Doremus, when a passing taxi driver informed them that a plane had just crashed into the World Trade Center. Biggart rushed home, retrieved three cameras and made his way to Ground Zero, where he started snapping photographs of the burning Twin Towers. Shortly after the South Tower fell, he spoke to his wife on the phone, telling her, “I’m safe. I’m with the firemen.” But some 20 minutes later, the North Tower collapsed, crushing Biggart under a mountain of debris. He was the only professional photographer killed while covering the 9/11 attacks.

Recovery workers found Biggart’s body, as well as his cameras, film cartridges, press credentials and equipment, four days after his death. A colleague managed to retrieve more than 150 images from his Canon’s memory card, revealing a final snapshot timestamped just seconds before the North Tower’s collapse: “a wall of smoke, looming over the wreckage” of the South Tower,” according to Smithsonian.

“I am certain if Bill had come home at the end of that day, he would have had many stories to tell us, as he always did,” writes Doremus on a memorial website dedicated to Biggart. “And had we asked how it really was, he would have said, ‘Take my advice, don’t stand under any tall buildings that have just been hit by airplanes.’”

Cell phone used by Mayor Rudy Giuliani

Embroiled today in legal and financial troubles, politician and lawyer Rudy Giuliani won accolades in 2001 for his leadership in a time of tragedy. Then at the end of his seven-year stint as New York City’s mayor, Giuliani used this Motorola i1000plus cell phone to coordinate emergency efforts on that September day. Arriving at a command center on the 23rd floor of World Trade Center Building 7 just after the second plane hit, he was evacuated as debris threatened to topple the building. Giuliani “remained at the center of the crisis for the next [16] hours,” according to the museum, which also houses the mayor’s windbreaker, boots, coat and cap in its collections.

Giuliani’s cell phone isn’t the only one in the museum’s 9/11 collection: A bright green Nokia phone used by Long Island Railroad commuter Roe Bianculli-Taylor and a boxy Ericsson T28 used by Bob Boyle, who worked near the World Trade Center, both testify to the importance of communication during a crisis.

“Cell phones were not as ubiquitous in 2001 as they are now,” says Yeh. “And they certainly did not provide the relief that one might imagine, for instance, in New York City, where cell towers went down. With millions of people trying to call, it was impossible to communicate. And not everyone had cell phones, so this sense of chaos and terror was made worse.”

Melted coins recovered from the World Trade Center

When Flights 11 and 175 struck the World Trade Center’s North and South Towers, respectively, their jet fuel sparked intense, multi-floor fires that reached temperatures of up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit. “The contents of the building[s]—desks, papers, carpets, ceiling tiles and even paint—fueled the fire,” according to the museum. “After the collapse, the fires continued to burn for weeks.”

Among the warped, melted objects found in the towers’ debris was this clump of coins. A similarly charred tin filled with melted coins and burned paper was recovered from a damaged office at the Pentagon. Fused together by the flames, the pile mirrors the “twisting, wrenching and tortured steel” and aluminum fragments similarly recovered from the wreckage, said Shayt in a curator reflection.

“It took five or six trips to finally find the steel that we now have,” Shayt added. “Steel that is manageable in size and yet robust enough to reflect the size and grandeur of the World Trade Center. Also steel that could be identified by its tower and its floor level.”

Sweatshirt worn by first responder Ivonne Coppola Sanchez

A more recent addition to the collection, this sweatshirt was worn by Ivonne Coppola Sanchez, a New York Fire Department Emergency Medical Services worker, as she searched for survivors at Ground Zero. Later, when Coppola Sanchez was working at a makeshift morgue, she encountered photographer Joel Meyerowitz, who snapped a portrait of her wearing the sweater.

A few years after 9/11, the nonprofit New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health (NYCOSH) featured Meyerowitz’s photo of Coppola Sanchez in a bilingual ad campaign encouraging first responders and volunteers to seek compensation for health issues linked to the attacks. (According to the World Trade Center Health Program, which provides medical monitoring and treatment for survivors and responders, conditions reported by those at Ground Zero range from asthma to cancer to post-traumatic stress disorder.)

The Spanish-language subway ad featured in NMAH’s collections speaks “to one personal story of being a first responder working at Ground Zero,” says Yeh. “To tie it all together, [Coppola Sanchez] later fell ill herself.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/b6/e8b60b28-53dc-4393-a52c-d5f55033ed02/screen_shot_2021-08-26_at_24730_pm.png)

Apron from Nino’s Restaurant in New York City

Two days after 9/11, Nino’s Restaurant, a family-run business on Manhattan’s Canal Street, began offering free meals to World Trade Center recovery workers. For the next seven months or so, the restaurant remained open around the clock, serving thousands and acting as a place of refuge for weary first responders. “We’ve made a commitment to keep our doors open until our city is rebuilt, healed and up-and-running,” said owner Antonio “Nino” Vendome at the time. “Constant donations of food and the time of volunteer chefs and waiters” ensured that the restaurant could keep its commitment, Vendome added.

When Shayt visited Nino’s, he noticed three aprons hanging behind the bar, all “loaded like pizzas with patches—from Canada, and England, and the U.S.—small towns and large.” Each patch represented a firefighter, police officer, Red Cross worker or other first responder who’d donated a piece of their uniform as a token of thanks.

After getting to know Vendome, Shayt asked if he’d be interested in donating one of the aprons to the museum. Vendome readily agreed.

“The aprons, even one apron, unified that story for us very well,” Shayt later said. “There are 65 patches on that apron, from towns like Dayton, Ohio, and Boston, Los Angeles, and Boise, Idaho. Fire, rescue, even civilian work. Patches from Con Ed, from the FBI and the Customs Service, left at Nino’s.”

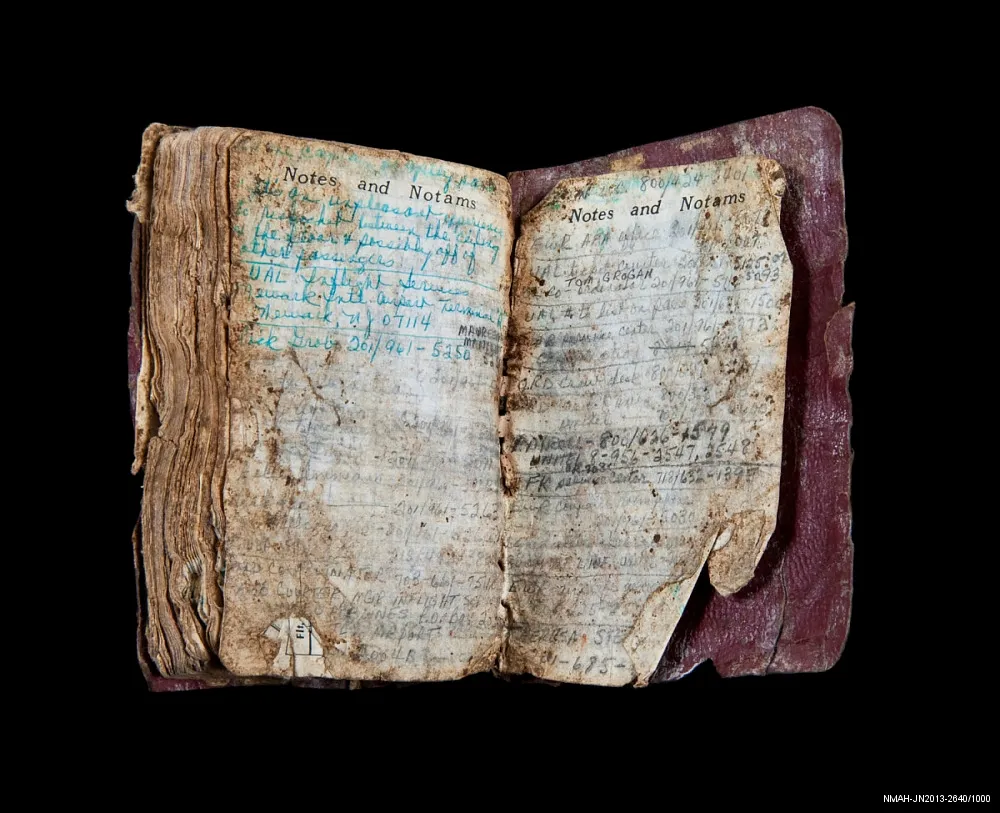

Lorraine Bay’s Flight 93 logbook and in-flight manual

Curators tasked with collecting objects related to United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, on the morning of September 11, faced an obvious obstacle: As curator Peter Liebhold later reflected, “There really was not much left, so it was very difficult to collect what did transpire, and the bulk of material was related to the public response to the events.”

The few surviving tangible traces of the hijacked flight include a crew log and an in-flight manual owned by Lorraine Bay, a 58-year-old flight attendant with 37 years of experience. In the logbook, Bay recorded the details of each trip she flew, penciling in flight numbers, dates and other information in blue link. The Philadelphia native took similar care with her in-flight manual, covering the guide in personalized notes indicating what to do in case of an emergency. Among the nine pages recovered from the wreckage is a list of instructions for responding to bomb threats—a fitting discovery, as Flight 93’s hijackers had threatened passengers by stating they had a bomb on board.

“Lorraine is here … because we wanted to show the importance of flight attendants in travel, that they are highly experienced, highly trained individuals,” says Yeh. “They’re not just there to help you board or give you drinks. And that’s where the flight manual comes in.” (Outside of these documents, a small number of passengers’ personal effects—a wedding ring, jewelry, photos, wallets and more—survived the crash and were returned to victims’ families.)

Of the four planes hijacked on 9/11, Flight 93 was the only one that failed to reach its intended target. Exactly what happened that morning remains unclear, but cockpit voice recordings and phone calls made by those on board suggest they collectively decided to fight back. None of the flight’s 33 passengers or 7 crew members survived the crash.

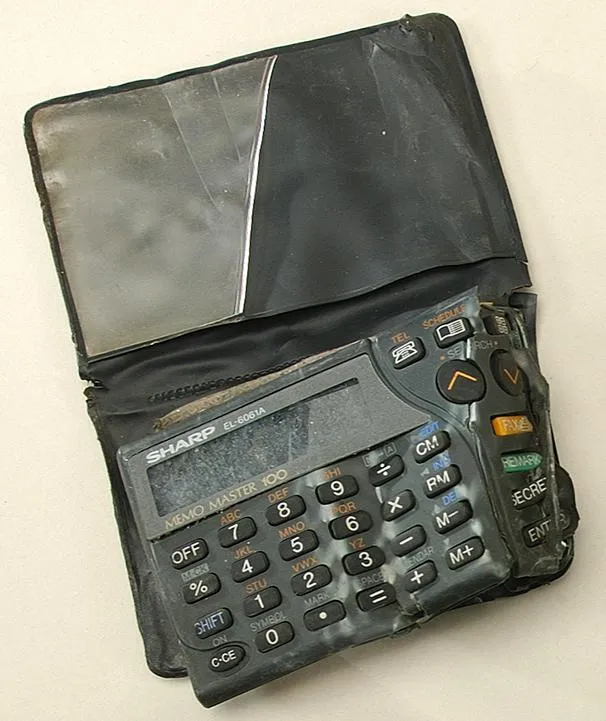

Pentagon office supplies

American Airlines Flight 77 struck the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m. on September 11, killing all 64 passengers and 125 people inside the Department of Defense headquarters. The impact knocked this clock, which hung on a wall at the Pentagon helipad firehouse, to the ground, stopping its hands at 9:32 a.m. (The clock was apparently several minutes behind.) Dennis Young, a firefighter who’d been trapped by debris when the firehouse’s ceiling collapsed, later donated the eerily frozen clock to the museum.

Other everyday items recovered from the wreckage at the Pentagon include a partially melted pocket calculator, a baseball desk ornament inscribed with the phrase “Sometimes you just have to play hardball,” a pocket New Testament, singed postage stamps and a copy of Soldiers magazine.

“I think objects tend to have the ability to connect people in an emotional and perhaps a visceral way with an event in the past,” said curator William Yeingst after the attacks. “In this case, these objects … from the Pentagon were in a sense witnesses to this larger event in American history.”

Uniform worn by Pentagon rescuer Isaac Ho‘opi‘i

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/5f/125fecbc-eb8d-40cb-b6c8-22eebc9f6bac/jn2023-00275.jpg)

Isaac Ho‘opi‘i, a K-9 police officer at the Pentagon, was taking his canine companion, Vito, to the vet when he received an unexpected call over the radio: “Emergency. Emergency! This is not a drill. A plane has crashed into the side of the Pentagon.” Blaring his cruiser’s siren, the Hawaii native headed back to Arlington, driving so fast that he actually blew out his transmission.

Ho‘opi‘i carried eight people—some dead, others still hanging on—out of the burning building. But flames and “thick black smoke billowing everywhere” soon made it impossible to enter the Pentagon again, according to Yeh.

“People trying to escape the building got turned around and couldn’t find their way out,” the curator adds. To guide them, Ho‘opi‘i used his powerful baritone, standing at an exit and shouting for those in hearing distance to follow his voice. “Many people remember hearing that voice in the darkness and following his voice to safety,” says Yeh. Today, the museum houses Ho‘opi‘i’s uniform, as well as Vito’s collar and shield, in its collection.

Flight 77 airplane fragment in patriotic box

The morning of September 11 found Penny Elgas, then an employee at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, on her way to work. Stuck in traffic on a highway right by the Pentagon, she spotted a plane flying low overhead, “floating as if it were a paper glider.” As Elgas watched in horror, it “gently rocked and slowly glided straight into the [building],” leaving the “entire area … awash in thick black smoke.”

Upon arriving home, Elgas realized that a piece of the plane had landed in her car’s backseat, perhaps dropping in through the sunroof or flying in via an open window. Measuring 22 inches long and 15 inches wide, it was “all plastic and fiberglass” and appeared to be part of the Boeing 757’s tail. A layer of white paint covered its surface.

According to the museum, Elgas felt it was “her patriotic duty to preserve the fragment as a relic, [so] she crafted a special box and lined it with red, white and blue material.” Elgas later donated the artifact—complete with her specially crafted container—to the Smithsonian.

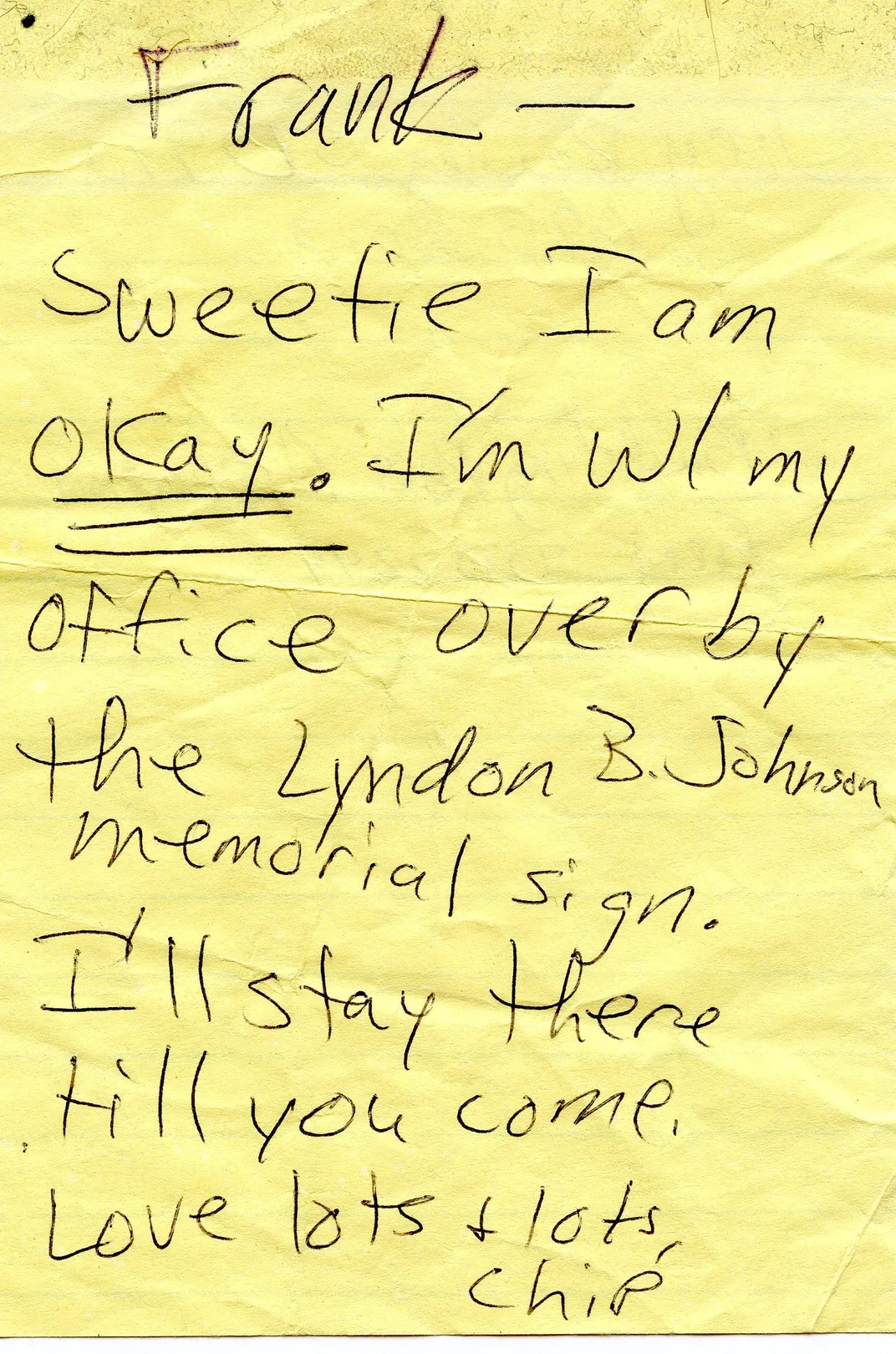

Note from Daria Gaillard to her husband, Frank

In the event of an emergency, Daria “Chip” Gaillard and her husband, Frank—both members of the Air Force who worked at the Pentagon—had agreed to meet in the parking lot by their car. On 9/11, Daria reached the couple’s car first; unable to remain in the parking lot due to safety concerns, she left her husband a brief note: “Frank—Sweetie I am okay. I’m w/ my office over by the Lyndon B. Johnson Memorial Sign. I’ll stay there till you come. Love lots & lots, Chip.” She underlined “okay” three times.

“It’s a very simple handwritten note,” says Yeh. “It speaks to how we communicate during emergencies and disasters, and what happens if your familiar tools”—like the ubiquitous cell phones of today—“are not available.”

After finding Daria’s note, Frank successfully reunited with his wife. Per a museum blog post, the couple dedicated the rest of the day to aiding the evacuation of the Pentagon’s daycare center.

Balbir Singh Sodhi's Sikh turban

Four days after 9/11, a gunman fatally shot Balbir Singh Sodhi, an Indian immigrant who owned a gas station and convenience store in Mesa, Arizona. Seeing Sodhi’s turban, the killer had assumed his victim was Muslim. In fact, the 52-year-old was a follower of the Sikh faith. Shortly before his death, he’d made a heartbreakingly prescient prediction about people’s inability to differentiate between Sikhs and Muslims, both of whom faced an uptick in hate crimes following the attacks.

“All Sikhs will be in trouble soon,” Sodhi’s brother recalled him saying. “The man they suspect, the one they show on television, has a similar face to us, and people don’t understand the difference.”

According to the museum, which houses one of Sodhi’s turbans in its “American Enterprise” exhibition, Sodhi immigrated to the U.S. at age 36. He initially settled in California, where he made a living as a taxi driver, but later relocated to Arizona, where he and his brother pooled their money to buy their own business. Sodhi was planting flowers in front of his gas station when the gunman drove by, shooting him in the back five times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/e7/dee71296-d705-402f-96d0-2d2bb4b3c2d8/mobile_911.jpg)

:focal(605x308:606x309)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/ae/9aaeb296-1689-411c-8aef-8ca19a409433/crew_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)