Thirty Years Ago, an Artificial Heart Helped Save a Grocery Store Manager

The Smithsonian, home to the Jarvik 7 and a host of modern chest-pumping technologies, has a lot of (artificial) heart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/1c/af1c04e0-592a-40a5-a069-b0d334eee751/jarvik7web.jpg)

Judy Chelnick still remembers the first time she held an artificial heart. Having just begun working at the Smithsonian Institution in the fall of 1987, she donned her curatorial gloves and felt the museum’s newly acquired Jarvik 7, which was part of an exhibition celebrating the National Institutes of Health’s centennial. The heart, which looks like a pair of Minions' goggles, was lighter and smoother than she’d anticipated.

“That was my first Smithsonian ‘Oh wow’ moment—holding the Jarvik 7,” says Chelnick, a curator of medicine and science at the National Museum of American History. “To hold it was an absolute thrill,” she says.

Through the gloves, the Jarvik 7 felt “almost like a piece of Tupperware,” Chelnick says. And the two ventricles on the artificial heart are held together by Velcro, a peculiarity that “always strikes people as different, interesting and strange,” she adds.

Robert Jarvik, president and CEO of Jarvik Heart (founded in 1988), created and produced the total artificial heart in the mid-1970s with University of Utah researchers. In addition to the artificial heart, Jarvik invented the battery-size Jarvik 2000 blood pump.

The particular heart which Chelnick handled was implanted 30 years ago this week in the patient Michael Drummond, an assistant manager at a Phoenix grocery store. On Aug. 29, 1985, the 25-year-old became the sixth recipient and the youngest at the time to receive an artificial heart. It was the first time a heart pump was used as a "bridge transplant" to prolong life until a human heart could be found. Drummond received a human heart nine days later. He lived nearly another five years.

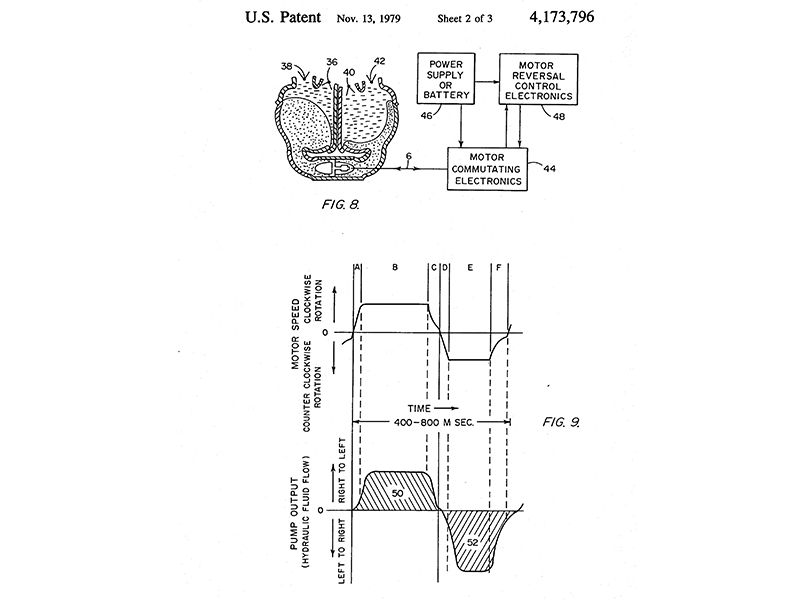

With the approach of the anniversary of that heart transplant, the American History Museum very recently received a donation from the Tucson, Arizona company SynCardia of a duo of modern hearts—a SynCardia 70cc Total Artificial Heart and a SynCardia 50cc Total Artificial Heart, along with a slice of the 70cc model which allows visitors to see the inside of the ventricle—a backpack and a portable driver. The latter, which is external to the body, powers the heart. Jarvik's 1977 prototype of his famous artificial heart is currently on view in the museum's new exhibition "Inventing in America," a collaboration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

The first successful human heart transplant was performed by South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard on Louis Washkansky on Dec. 3, 1967; the patient, a Cape Town grocery store owner, lived another 18 days. Nearly 15 years later, surgeon William DeVries implanted a Jarvik 7 artificial heart in dentist Barney Clark at University of Utah Hospital on Dec. 2, 1982. That procedure, after which Clark lived 112 days, was the first permanent artificial heart implanted in a patient.

The Jarvik 7 that Drummond received nearly three years later was history’s first authorized, successful transplant of an artificial heart as a “bridge” to a human heart. The word “authorized” is also important, as another 1969 artificial heart transplant remains shrouded in controversy; that patient lived less than two days following the transplant. The New York Times called the tension between the doctors, who had collaborated on the technology, in which one lifted the artificial heart from his former partner’s lab without the partner or the university’s permission, “medicine’s most famous feud—and certainly one of its longest-lived.”

The artificial heart that Drummond received was the product of a company that was first Kolff Medical (Robert Jarvik was CEO); in 1983 it was renamed Symbion; in 1990 the FDA shuttered Symbion (for violations of FDA guidelines and regulations), and its artificial heart technology was transferred to CardioWest; in 2001, the company became SynCardia.

Thirty years after Drummond received his heart, artificial hearts haven’t changed all that much, says Craig Selzman, chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at University of Utah, the site of Barney Clark's 1982 transplant.

“Interestingly, the Jarvik 7 is quite similar to the FDA-approved Total Artificial Heart (TAH) that is now owned by SynCardia,” Selzman says. “Of course, there are a few modifications over the last 30 years, but it is functionally very similar to the device that Barney Clark and Michael Drummond received.” Despite the NIH’s efforts to move the field along, “the Jarvik-7 still is the essential design that is on the shelf today,” he adds.

Artificial hearts and other artifacts found in the museum's medical collections are donated by businesses, institutions, medical facilities and families because they are historically significant. (Drummond's Jarvik 7 was later donated to the Smithsonian by the University Medical Center of the University of Arizona, where his surgery took place.)

“Sometimes there's the yuck factor, but you get that a lot with our collection in general,” says Chelnick. But, she adds, most visitors who see the artificial hearts on exhibit and in education programs are fascinated by them. “Many are in awe that this mechanical device can be implanted in someone’s body and take the place of a native heart,” she says. In demonstrations, museum staff blow into the ventricle (via a tube) and cause the diaphragm to contract and expand.

Selzman believes that keeping the history of heart transplants alive is both essential for students of the field and provides future generations with “incentive to innovate for our patients.”

“The history of the development of mechanical support for these extremely ill heart patients is one of the most fascinating stories in all of medicine,” he says, admitting a bias. “But it carries intrigue, personality clashes and larger-than-life pioneers that span engineering, surgery, medicine, and of course the courageous patients. I challenge you to find more compelling stories than those that surround this field.”

One of the new hearts recently donated can be viewed on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Saturday, at 11 a.m. and 2:30, at the National Museum of American History's Wallace H. Coulter Performance Plaza Stage in the presention "How to Fix a Broken Heart?"

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)