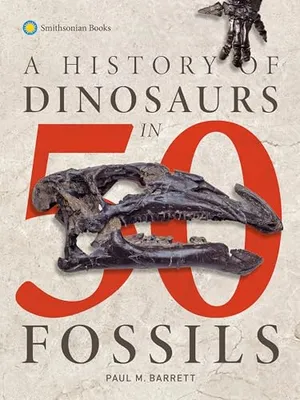

Dinosaurs thrived on our planet for many millions of years. Scaly and feathery, toothy and armored, the reptiles evolved into a magnificent array of forms that paleontologists are still uncovering year by year. Encapsulating such longevity and variety is a challenging task, but paleontologist Paul M. Barrett does just that in the new release from Smithsonian Books, A History of Dinosaurs in 50 Fossils.

Humans were awed by dinosaurs before we even had a name for them. Petroglyphs made by Indigenous cultures alongside dinosaur tracks, or even fashioned to look like footprints left by three-toed dinosaurs, indicate that people have been fascinated with dinosaur fossils for centuries, if not millennia.

European scholars first had to realize that the Earth is far older than any text, an awakening that only began to take hold in the 17th century, and that fossils are remains of once-living creatures rather than just curious rocks. By the dawn of the 19th century, European naturalists were beginning to realize that Earth’s rocks were full of fossils representing unknown, extinct species, including reptiles larger than anyone had ever seen. The English naturalist William Buckland was one of the scholars who’d become transfixed by fossils, and on February 20, 1824, he described one such creature from bones and teeth found in Stonesfield. Megalosaurus, as he named it, was an enormous reptile that we now recognize as the first dinosaur to receive a scientific name.

Barrett begins the book with the discovery of Megalosaurus and the question of “What is a dinosaur?” before taking readers on a Mesozoic tour of dozens more dinosaurs that inform our 21st-century understanding of what these reptiles were like. Favorites such as Triceratops and Stegosaurus populate the pages, visualized with photos of fossils at the Natural History Museum in London, where Barrett works, but readers will undoubtedly meet some unfamiliar species, too. The small, poorly known Nyasasaurus from Tanzania stands out as the best candidate for the earliest known dinosaur, while the long-necked Haestasaurus gives a close-up look at dinosaur skin, and the big-eyed Haplocheirus suggests that some dinosaurs were nocturnal.

“Rather than being strictly chronological or dealing with things in historical order, I wanted to introduce the subject by first explaining what dinosaurs actually are and where they fit into the overall tree of life,” Barrett says. The resulting dinosaur list became what Barrett refers to as a dramatis personae, the fossils that would best represent our ever-changing understanding of the “terrible lizards.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ec/82/ec825b49-31d3-44d0-b78f-dcada4827b7c/triceratops.png)

The book’s focus on fossils lets each piece of dinosaur history tell its own story. “It roots the study in tangible things, which allows the book to go beyond stereotypical stories and highlights all kinds of connections that might otherwise have been missed,” says King’s College London science historian Chris Manias.

Naturally, picking only 50 fossils to represent the big picture of dinosaur science required great care. “I had to make a number of tough choices when thinking of which dinosaurs to include,” Barrett says. The book had to cover the vast diversity of dinosaur groups and forms through time and also represent various aspects of dinosaur biology. We know more about dinosaurs than ever before, from their coloration to their social behavior, represented by such a large volume of fossil finds. Making a shortlist of species can be painful for a dinosaur specialist.

To navigate the task, Barrett split the selected dinosaurs between sentimental and representative fossils from around the world. “The choices are largely personal,” Barrett says, “dinosaurs I’ve worked on, look after in the museum, or that are particular favorites.” To pay tribute to the growing international nature of paleontology, Barrett also chose some fossils found and displayed far from London. “It was important to mention dinosaurs from every continent, and to include a number of key animals that reveal new information about dinosaur biology or behavior.” And while birds receive a brief mention given the fact that they are dinosaurs, too, Barrett keeps his focus on non-avian species from the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous heyday of the dinosaurs. “Extinct birds are deserving of a book in their own right,” he says.

Naturally, compiling a shortlist of 50 dinosaurs required that even some favorite species had to be left off. “I’d really liked to have said more about Scelidosaurus,” an armored dinosaur that “is known from several beautiful and almost complete skeletons from the U.K.,” Barrett says. At about 191 million years old, Scelidosaurus sits near the origin of the armored dinosaur lineages that led to the plated, spike-tailed Stegosaurus and later, club-tailed Ankylosaurus, standing out from more fragmentary finds as one of the best-preserved dinosaurs from England. Given that a new dinosaur species is described about every two weeks, there will always be more dinosaur species to discuss than there is space to include in such books.

Even so, Barrett did not only focus on celebrity species such as Spinosaurus or famous specimens like “Dippy” the Diplodocus. Some fossils included in the new book have never even been fully described by experts. “One of the least familiar fossils in the book is an amazingly preserved dinosaur braincase that includes natural molds of the brain, cranial nerves and inner ears,” Barrett says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b3/98/b3980445-93ea-4c78-9b25-9a97a346de39/stegosaurus.png)

“It struck me just how amazing some of our less famous fossils can be,” he notes, adding that many fossils around the world either await a full scientific description or may even still be encased in plaster jackets from the field. In fact, Barrett says, the book includes a dinosaur egg that was until recently mistaken for an agate. Sometimes the latest dinosaur discoveries don’t come from the field, but from museum shelves where fossils have been waiting for a researcher to take another look at them.

Such finds are constantly changing what we think about dinosaurs, and the new book flows from decades of discoveries that have dramatically altered our image of dinosaur lives. If the same book had been written 25 years ago, for example, dinosaurs that we now know had feathers would have been illustrated as wholly scaly, and paleontologists would have said that we’ll never know original dinosaur colors, a line of research that is now growing. The ways dinosaurs grew up, reproduced and made nests used to be treated as mysteries, Manias notes, but now can be presented in detail.

“Many of the advances made over the past 25 years, roughly the length of my career, have been due to amazing technological developments in imaging and geochemistry, as well as a surge of new fieldwork,” Barrett says.

Dinosaurs have come a long way since that February day when Buckland named his mysterious Megalosaurus, and Barrett’s new book helps set the stage for future discoveries that will certainly keep coming. “That’s the beauty of science,” Barrett says. “It keeps building on what was there before.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(659x559:660x560)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c8/8b/c88be6c8-ae40-4049-88cb-99d882f8323c/allosaurus.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)