This Locket Memorializes a Black Activist Couple Murdered in a Christmas 1951 Bombing

Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore attracted the KKK’s ire for their tireless promotion of civil rights in the Jim Crow South

:focal(640x440:641x441)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/21/6221106b-a8c2-4e0f-9ba1-e06ac14da85c/locket.jpg)

Open the locket, and two faces appear: Harriette V. Moore, a young Black woman seen gazing into the distance against a backdrop of tree branches, and her husband, Harry T. Moore, who looks directly into the camera. Taken during the early to mid-20th century, when Black Americans in the Jim Crow South endured segregation, discrimination and unremitting racial violence, the photographs testify to the civil rights activists’ tender partnership—and offer a glimpse of two lives cut short by a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) bombing on Christmas 1951.

December 25 marked both Christmas Day and the Moores’ 25th wedding anniversary. The couple, who’d dedicated much of their married lives to fighting for racial equality, celebrated with a slice of leftover holiday cake before retiring for the night in their Mims, Florida, home. A bomb hidden beneath their bedroom floorboards exploded around 10:20 p.m., fatally injuring both in a blast that could be heard several miles away. Harry died en route to the hospital; his wife succumbed to her injuries nine days after the attack. The Moores’ oldest daughter, Annie Rosalea, or “Peaches,” and Harry’s mother were in the house but survived without sustaining serious injuries.

Despite multiple investigations spanning decades, no one was ever arrested or tried for the murders. A 2008 review of the case by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) named four renegade Klansmen as the likely conspirators, but all were dead by the time they were identified. The Department of Justice closed the Moores’ file in 2011.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/a6/4ea63328-6800-414b-bd29-f33da020606a/gettyimages-494781192.jpg)

The Moores “are early unsung heroes of the civil rights movement,” says Spencer Crew, emeritus interim director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). William Pretzer, a senior curator at the museum, agrees that both were trailblazers. While most surviving documents carry Harry’s signature, “they operated as a couple,” says Pretzer. “He was, obviously, the most prominent, but she was his partner in every way possible.”

Harry gave the locket to his wife as a keepsake at an unknown point in their relationship. Their daughter Evangeline later donated it, along with watches and a wallet, to NMAAHC, where the objects are on display. (The youngest of the couple’s two children, Evangeline was working as a clerk typist in Washington, D.C. when the attack occurred and only learned of her parents’ injuries upon arriving in Florida two days after Christmas.) Pretzer deems the pendant “the most poignant artifact” included in the donation. The museum also houses as-yet-unprocessed papers belonging to the Moores, including the contents of a briefcase apparently taken by the FBI at the beginning of the 1951 investigation and rediscovered decades later.

Seventy years after the bombing, the Moores’ story is lesser known in the annals of the civil rights movement. Pretzer attributes this oversight partly to the long-standing idea that the campaign to expand African American rights took place between 1954 and 1968. That kind of thinking acts as a “filter,” making it difficult to recognize the achievements of earlier generations, he says. The curator also points out that events prior to 1954 were often seen as local or regional issues rather than as part of a national movement. At the time, adds Crew, the NAACP focused more attention on what was happening nationally than on events at the grassroots level.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3f/24/3f24d3a2-9045-4832-892c-ff33a6e1201b/gettyimages-136110022.jpg)

In recent years, younger scholars familiar with the well-covered stories of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. have demonstrated an eagerness to flesh out new truths from an earlier era, according to Pretzer. The Moores’ story is one of many such accounts now experiencing a resurgence in interest.

Born in Houston, Florida, in 1905, Harry lived in Jacksonville with three aunts—a nurse, a school principal and a teacher—following his father’s death in 1914. The trio instilled in him a lifelong passion for learning. After graduating from high school, he began teaching at a segregated school in Brevard County, where he met his future wife. After the couple wed in 1926, Harry became a principal. The couple’s first child, Annie Rosalea, was born in 1928. Evangeline followed in 1930. Eventually, both Moores earned college degrees from Bethune-Cookman College.

At work, the couple fought to improve conditions for Black teachers. Supplies and learning materials were shabby, and teachers received less pay than their counterparts at all-white schools. In 1937, with the assistance of NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, Harry filed the Deep South’s first lawsuit calling for equal pay for teachers. The suit didn’t move forward in state court, but it sparked other challenges in federal court that eventually equalized salaries for Florida’s teachers.

Harry, who’d started working for the NAACP in 1934, rose to the rank of executive secretary of the Florida Conference of NAACP branches by 1941. His wife worked by his side both at school and in the budding movement to expand African American rights. Together, the pair helped the Florida NAACP grow to more than 10,000 members across 60 chapters.

In addition to advocating for equal pay, the Moores worked to expand Black voting rights. A 1944 Supreme Court ruling declared that all-white primary elections were unconstitutional, paving the way for Harry’s establishment of the Florida Progressive Voters League that same year. He made Black votes count: Only 5 percent of Florida’s eligible African American residents were registered to vote in 1934. By 1950, this figure had risen to 31 percent. According to the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Cultural Complex, Harry’s organization helped register more than 100,000 Black voters.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/2b/6e2b1286-d785-4640-9b3b-5754a8050e0a/asdfasf.jpg)

In 1946, the Moores’ school district declined to renew their teaching contracts—a “common tactic of intimidation used to silence those who fought for civil rights,” as attorney William E. Nolan wrote in a 2011 notice recommending the closure of the couple’s murder case. Blackballed from securing another teaching position, Harry decided to become a full-time organizer for the Florida NAACP.

Between 1880 and 1940, Florida had the highest number of lynchings per capita of any U.S. state. As part of his efforts to combat this campaign of racial terror, Harry took a stand in the 1949 Groveland Four case, which found a 17-year-old white woman accusing four Black men of raping her. A white mob hunted down and killed one of the accused. The other three were found guilty but had their convictions overturned by the Supreme Court in 1951. Before the retrial, Sheriff Willis B. McCall shot two of the men, claiming they’d tried to escape from his car while still handcuffed. One died, while the other survived by pretending to be dead. The Stetson-wearing McCall faced no criminal charges.

Harry supported the defendants and accused McCall and other law enforcement officers of perpetuating racial violence. “He wrote to the governors, he wrote to the national offices of the NAACP seeking their intervention, he wrote to the president ..., he wrote to the Department of Justice, anyone who he thought could bring aid and attention to these situations,” said historian Tameka Bradley Hobbs, author of Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home: Racial Violence in Florida, in a 2018 documentary about the case. A judge finally exonerated the Groveland Four this November.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ac/59/ac596107-23cd-45cd-a21d-633bb55badcf/home_of_assassinated_florida_naacp_president_harry_moore_mims_fl.jpeg)

In his speeches and letters, Harry tried to steer the consciences of white leaders who looked the other way when Black Americans suffered and died at the hands of racists. “You need to parse your words carefully,” says Crew, “because if you just get them angry, you’ve lost. So you’ve got to ... try to appeal to their sense of humanity, if it exists, in the hopes that it’ll cause them to act differently.”

Harry quickly gained a reputation as both an agitator and a threat to white control. Like her husband, Harriette delivered speeches around Florida promoting equal rights. During her time as a teacher, she shared Black literature with her students instead of relying on outdated books that celebrated a white-centric view of history and culture.

The NAACP fired Harry as executive secretary in 1951, just weeks before his death. National leaders blamed him—instead of a doubling of dues—for a decline in membership. This setback coincided with an uptick in KKK activity in Florida. In response to growing pressure for change from people like the Moores, the local Klan leader declared war on the Catholic Church, the NAACP, B’nai B’rith, the Federal Council of Churches and other organizations that he identified as “hate groups.” This campaign, known as the Florida Terror, led to attacks on Catholic churches, synagogues and a Black housing project. It culminated in the murder of the outspoken Moores.

What made the couple assassination targets? “Black people got murdered for doing a hell of a lot less than Harry Moore,” says Pretzer. Moreover, the Moores “created a voting bloc. They gave African Americans in Florida agency, and they called into question the legal system.”

In 1952, Harry posthumously received the NAACP’s highest honor, the Spingarn Medal. Around the same time, poet Langston Hughes penned “The Ballad of Harry Moore,” a tribute that was later adapted into a song by a capella group Sweet Honey in the Rock.

Though the Moores’ deaths galvanized the civil rights movement more than a decade before the 1963 murder of Medgar Evers, their sacrifices were overlooked for decades. The couple do not appear on Alabama’s Civil Rights Memorial, which was dedicated in 1989 and includes the names of martyrs killed between 1954 and 1968. Renewed recognition only arrived in the early 2000s, when the Moore Cultural Complex opened in Mims. In 2013, the post office in Cocoa, Florida, was renamed in honor of Harry and Harriette, and three years later, both Moores received honorary doctorates from their alma mater, now called Bethune-Cookman University.

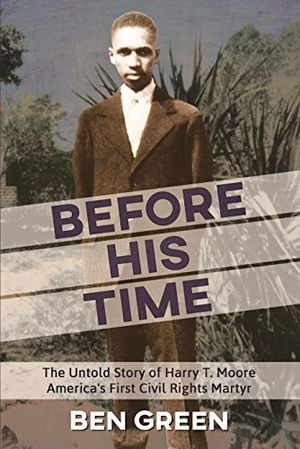

Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore, America's First Civil Rights Martyr

The sound of the bomb could be heard three miles away in the neighboring town of Titusville, but what resonates today is the memory of the important civil rights work accomplished by Moore.

Lack of knowledge about the Moores’ work extended into their own family. The couple’s grandson, Skip Pagan, says that his mother, Evangeline, and her sister, Annie, agreed not to let their pain show at their parents’ funeral and didn’t talk about the bombing for a long time. Pagan learned the vague outline of his grandparents’ lives and deaths as a child but says he was at least 40 “when I first heard the full story” by reading author Ben Green’s Before His Time: The Untold Story of Harry T. Moore, America’s First Civil Rights Martyr. Later, Pagan gained a clearer understanding of Florida officials’ oft-omitted role in persecuting Black Americans: The state “had a vested interest in protecting their legacy as a paradise for tourism.” Politics drove an effort to cover up the state’s dark past.

Over the years, Evangeline told Pagan stories about traveling across Florida with her father to deliver speeches he had written. “She talked about the experience of coming out in the dark and getting in the car and starting their passage home, only to see lights come on behind them, and then being trailed,” Pagan recalls. “She said sometimes it was for a couple of blocks, sometimes a couple of miles, sometimes it could actually be to the city limits or the county limits before they would just go dark.”

Memories of her father’s courage in the face of danger led Evangeline to dedicate her last years to preserving her parents’ story. “That was clearly what her mission was in life,” says Pagan, who took over for his mother following her death in 2015.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)