This Stunning New Atlas Explores Humanity’s Ancient Relationship With Space and the Universe

Written by the former chief historian of NASA, the book examines the evolution of our cosmic understanding—from early civilizations to the present day

:focal(1087x1884:1088x1885)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/70/bd/70bd51a5-28c4-40fb-b6cb-18be20134e6c/stsci-01ggf8h15vz09met9hfbrqx4s3_copy.png)

Since the dawn of civilization, our fascination with the universe has driven constant exploration. From viewing the skies as religious symbols, to astronomer Galileo Galilei’s groundbreaking discoveries, to NASA’s recent Europa Clipper mission, humanity’s intrigue with the cosmos has remained relentless.

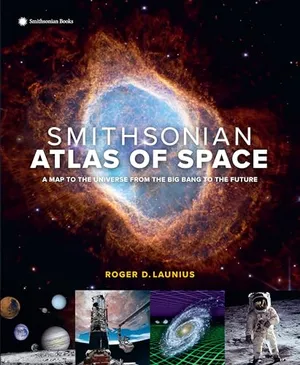

Roger Launius, former chief historian of NASA and former associate director of collections and curatorial affairs at the National Air and Space Museum, captures humanity’s cosmic journey in his new book, Smithsonian Atlas of Space, which serves as a map “from the Big Bang to the future.”

“The planets of the solar system, their moons, lots of asteroids—are places,” he says. “They are worlds, and each of them are different from each other.” And because of that, we’ve had to adapt our own understanding of them, he adds.

The atlas covers the expanse of the universe and the inner solar system, and it cycles through the lives and deaths of stars. It flings readers out to Neptune and Uranus, the farthest of the Jovian planets, only approached by Voyager 2 in the 1980s, and shows how our knowledge of Earth has shifted with the rise of spaceflight, allowing us to observe changes over time. The atlas even reflects on the future of space exploration, from the moon to Mars.

Smithsonian Atlas of Space: A Map to the Universe from the Big Bang to the Future

Journey to the farthest corners of the universe in this visually stunning coffee-table atlas by the former chief historian of NASA

As Launius writes in the introduction of the book, the atlas represents “a significant effort to place what we know about this beautiful universe, and how we know it.”

Launius notes that the book is a “progress report” on what we’ve learned so far. He plays little games, he says, asking himself, “What will be correct about this particular book 100 years from now? And what will have been superseded by new information? And what will have been proven to be just totally wrong?”

He hopes that readers come away with an understanding that the book is not a final word, and that they marvel at how much humanity has learned over a long period of time.

Before the mid-1990s, scientists knew very little about the planets beyond our solar system. Since then, they’ve discovered thousands. Launius writes that by this March, well over 5,000 exoplanets “had been confirmed by two or more separate sets of observations.” That number continues to grow.

“Something as dynamic as the scientific pursuit of knowledge about the universe changes almost daily,” he says.

The book also examines ancient beliefs about the universe, detailing how early civilizations developed ideas of the cosmos and what those ideas represent. Here, we explore some of these ancient beliefs and their evolution into what we know today about the universe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/81/31/81315b40-020d-412c-b8db-e12b354b254f/pia19419.jpg)

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians were characterized by their religious and astronomical structures, like this astronomical observatory from the sixth century B.C.E. found in the city of Kafr El-Sheikh. The observatory has a specific L shape with columns resembling Egyptian temples that show ancient astronomy’s ties with religious matters.

Like other ancient civilizations, the Egyptians also developed sophisticated calendars for timekeeping. They mapped individual stars and constellations in the sky. Many ideas developed by ancient Egyptians are considered advanced for their time, such as the hieroglyphs found in a 4,400-year-old pyramid that suggest they might’ve understood the origins of meteorites.

Babylonians

In Mesopotamia, the ancient Babylonians believed the sky acted like a dome where the sun, moon and stars crossed it slowly from east to west. And although these explanations don’t work in the context of what we understand of the universe today, some of the practices in Babylonian astronomy do, including cataloging stars and constellations, and regular observations of celestial events.

Certain aspects of these efforts to understand the cosmos had implications for daily activities, such as farming, Launius says: “When do you plant crops? When do you harvest crops? When will there be a new moon? When will there not?” Like other ancient civilizations, they were interested in calculating everything.

Ancient China

In ancient China, the explanation of the cosmos came from a mix of night-sky observations and religious and philosophical ideas. Some of the oldest star maps and earliest known records of sunspots were produced in China, starting around 1200 B.C.E.

One of the ancient Chinese systems includes the Han astronomical system (Han li), which predicted celestial events, from solstices and equinoxes to the motions of the planets, using the best instruments available and a staff of skywatchers. Adopted in 85 C.E., the system could calculate all the solar, lunar and planetary data for any year afterward, Launius explains in the book.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/57/c7570037-eb32-41f1-ab96-dd2fa5a30db1/stsci-01ga76q01d09hfev174svmqdmv_copy.png)

Maya civilization

Beliefs about the universe in the Maya civilization of Mesoamerica were defined by “cosmic trees.” The Maya believed in a stable universe with the Earth at the center. In the skies, they saw a heaven with 13 layers that encompassed the sun, moon and stars, Launius writes in the book. Each layer was represented by a different god.

The Maya also thought of a cyclical cosmos that was ruled by numbers and chronology. Their solar cycle calendar had 365 days and “still forms a model for the present calendar,” Launius writes.

Greeks and Romans

Greco-Roman ideas about the universe were the “linchpin” for most Western thinking, Launius says. In one of the ancient Greek systems, the universe was part of a great sphere split in two—an outer and inner realm—by the orbit of the moon.

A once-prominent idea about the universe was the geocentric Ptolemaic planetary system, created by the astronomer Ptolemy, positioning Earth at the center. People weren’t trying to deceive each other, Launius says, but “the tools, the instruments, the scientific knowledge that they had at the time gave them these sorts of answers.” It took about 1,500 years for the model to be replaced by the heliocentric Copernican system, formulated by astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, that described the sun in the central position.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/headshot_2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/headshot_2_thumbnail.png)