Three Generations of Inuit Women Defy Exploitation by Visualizing Resilience and Love

A grandmother, a mother and a daughter, all took up pen and ink to tell their stories

Andrea R. Hanley had long been an admirer of Annie Pootoogook’s pen and colored pencil drawings of contemporary Inuit home life. She was also aware of Pootoogook's impressive forebears—three generations of artists, influencing and impacting one another and their community and the art world in the process.

"Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait," a new exhibition on view at Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian at the Heye Center in New York City, traces the art and influences of an Inuk grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona (1904–1983), a mother Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002) and a daughter Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016).

The show features just 18 works total from the three prolific artists, but conveys a vast range of styles and expressions of life in their remote Eastern Arctic community on Dorset Island, Nunavut, Canada.

“It’s an amazing conversation that you hear and see,” says Hanley, the exhibition’s curator and the membership and program manager at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, where the show originated. “The discourse and dialog between these three are so powerful that it shows that [the number of works doesn’t] need to be enormous in order to really pack a punch.”

Each artist commands an impressive career and is “a master in her own right,” according to Hanley, and could have anchored her own solo exhibition. But for this show, the curators sought to tell a more nuanced story about tradition, legacy and family bonds, and how these shift over time—a word in the show’s title, akunnittinni, translates to “between us.”

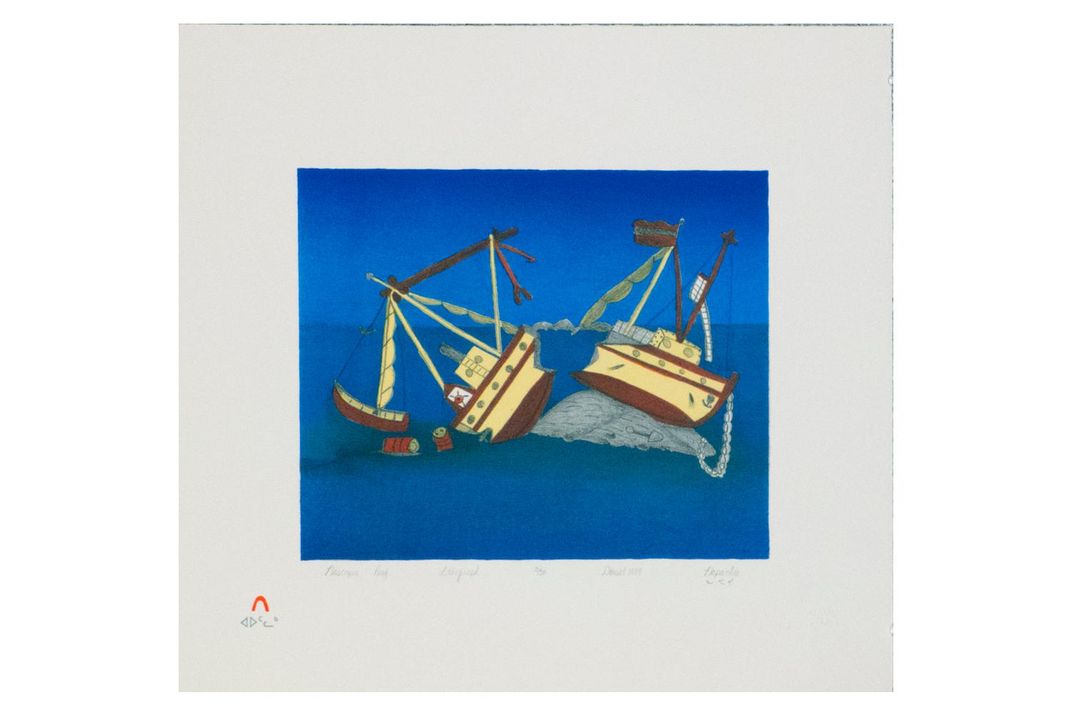

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/1b/7c1b9f27-1e58-44af-b139-8d3acec30b31/whalers_exchange_napachie_pootoogook.jpg)

“The grandmother painted more romanticized versions of the story she heard—of how the culture used to be,” says Patsy Phillips, director of IAIA. “The mother drew more of the darker side of the stories she heard [while] the daughter’s were much more current.”

The concept for the show took off when Hanley and Phillips visited the Yonkers, New York, apartment of Edward J. Guarino—an esteemed collector and archivist of Inuit art.

“He began pulling out large archival boxes of these amazingly beautiful prints,” says Hanley. “It was just one piece after the other that was a masterpiece.”

She was particularly interested in the connections of the three generations of the family. Her Navajo ancestry also helped drive her interest.

“Coming from a matriarchal tribe I was really drawn to this idea of these three generations of native women all from one family, this very strong family voice, coming from a tribal context,” says Hanley.

While the show tells the story of a specific family, it also reflects the larger story of the Cape Dorset arts community. Since the 1950s, Cape Dorset has called itself the “Capital of Inuit Art,” with printmaking and carving replacing the fur trade as the main local industry. A decade ago, it was declared the “most artistic municipality” in Canada, with 22.7 percent of its workers employed in the arts—at the time, that meant 110 artists in the 485-person labor force.

Pitseolak Ashoona embodies this shift in the region. After her husband passed away in the early 1940s, she became a single mother with 17 children to care for. Seeking a way to express her grief, and a way to earn money, she began creating art. First she sewed and embroidered goods and then made drawings, using graphite pencil, colored pencil and felt-tipped pens. It proved prolific as well as it created a profitable career—in the two decades she worked as an artist, Ashoona created more than 7,000 images.

A significant market for Inuit art was evolving in mainland Canada, facilitated in large part by Canadian artist James Houston, who lived in Cape Dorset. Houston introduced printmaking there, and helped promote and sell the crafts and art to the wider North American market.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/b3/45b3affd-2ebb-41c2-85f7-493c305aaa12/eating_his_mothers_remains_napachie_pootoogook.jpg)

Beginning in 1958, this practice became a formal co-operative with a print shop where artist-members produced stonecut prints, etchings and crafts, which were then sold through the Dorset Fine Arts center in Toronto. Eventually the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative established a sustainable art industry that continues to thrive. Its printmaking program, now known as Kinngait Studios, continues to release an annual catalogued collection of several dozen images as well as many commissions and special releases.

“They didn’t work in just one type of printmaking—they experimented with all types, like lithography, silk screen, the list goes on,” says Phillips.

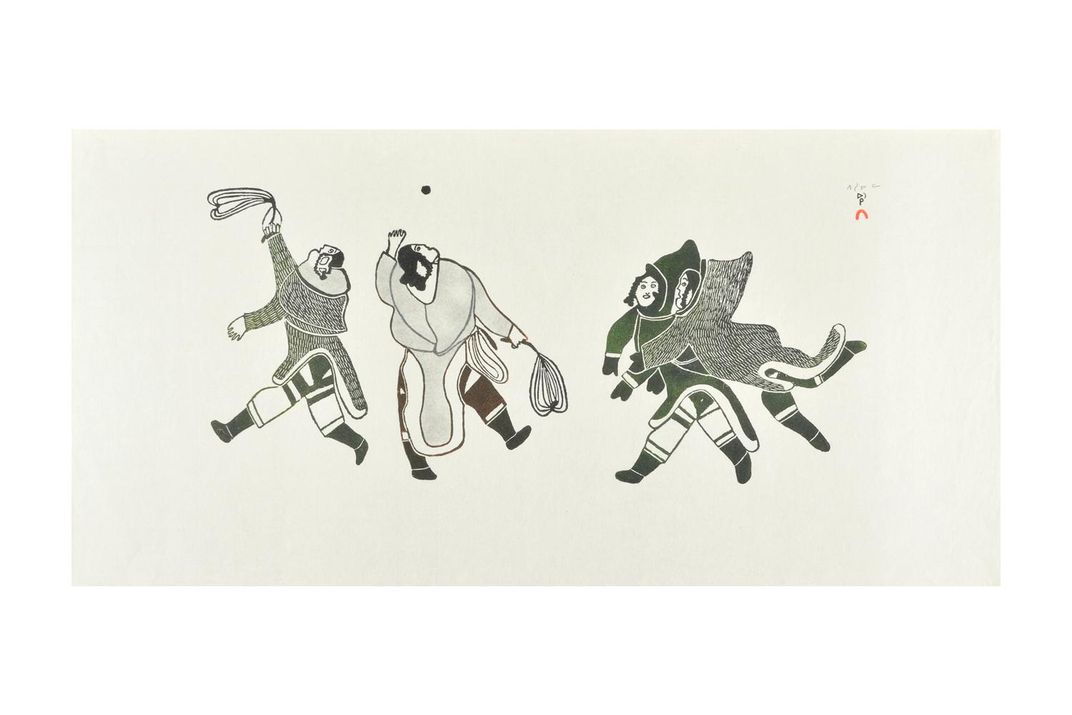

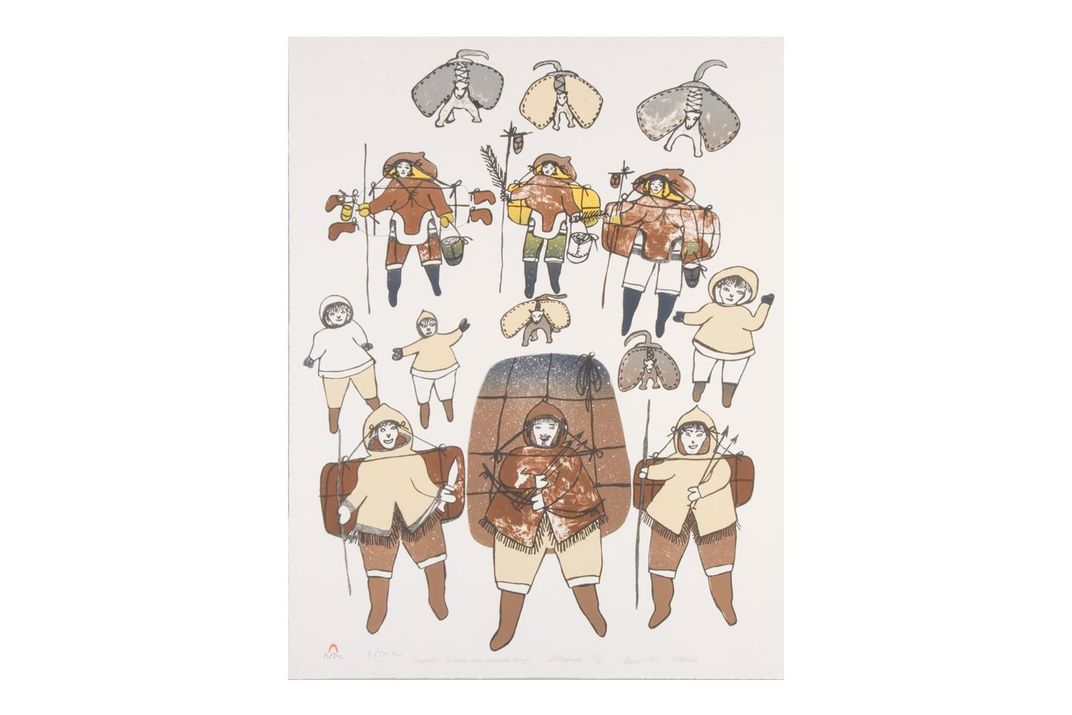

Ashoona was one of the pillars of this early Cape Dorset art industry. Her works in the show convey the lively style that appealed to a broad audience, and presents some of her typical subjects—spirits and monsters as well as sometimes idyllic treatments of daily life doing "the things we did long ago before there were many white men,” as the artist described it.

Hanley points to Pitseolak’s piece Migration towards Our Summer Camp, created in 1983, the year she passed away. It shows the family as they move to their summer home. Everyone has a smile on his or her face—seemingly even the dogs—and it reflects the bonds and warmth between members of the community.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/2f/cb2fb1bf-0b14-4c81-95d1-f824b89e1abe/trading_women_for_supplies_napachie_pootoogook.jpg)

“It’s looking toward this really great time in their lives,” Hanley says.

Besides working until her final months of life, Ashoona also raised artists, including sons Qaqaq, Kiawak, and Kumwartok who all became sculptors, and daughter Napatchie, who produced more than 5,000 artworks of her own from the time she began creating works in her mid-20s to her death at 64.

Napachie Pootoogook’s graphic art, using acrylic paint and colored pencils, reflects a distinct shift from her mother’s style of prints recording traditional Inuit life. From the 1970s on her work included darker themes such as abuse, alcoholism, rape and even cannibalism.

One of the drawings in the exhibition, Trading Women for Supplies, reflects the harsh suffering and exploitation faced by members of the community, particularly women.

“It’s contemporary indigenous feminist discourse at its truest,” says Hanley. “What these women go through and have gone through—their resilience, their strength, their struggle, their heartbreak, their love, and the family and what that means.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/86/3086595b-554b-43b0-bed6-9a3f9d5465c5/watching_the_simpsons_on_tv_annie_pootoogook.jpg)

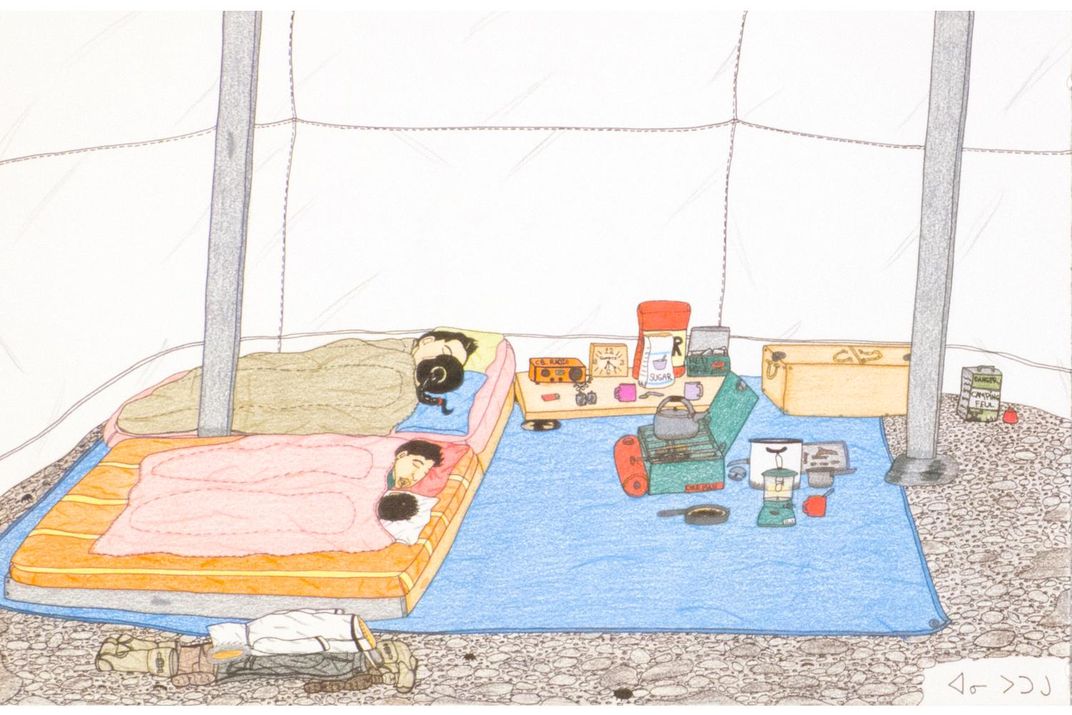

Annie Pootoogook, born when her mother was 21, began creating art in 1997 with the support of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative and rapidly established herself as a leading Inuit artist. She was less interested in the Arctic animals or icy landscapes of traditional Inuit artists, and instead used her pens and colored pencils to capture scenes of interior home life, drawing televisions, ATM cash machines, and her own furniture. Her simple, unsparing line drawings challenged what typically was thought of as “Inuit art.”

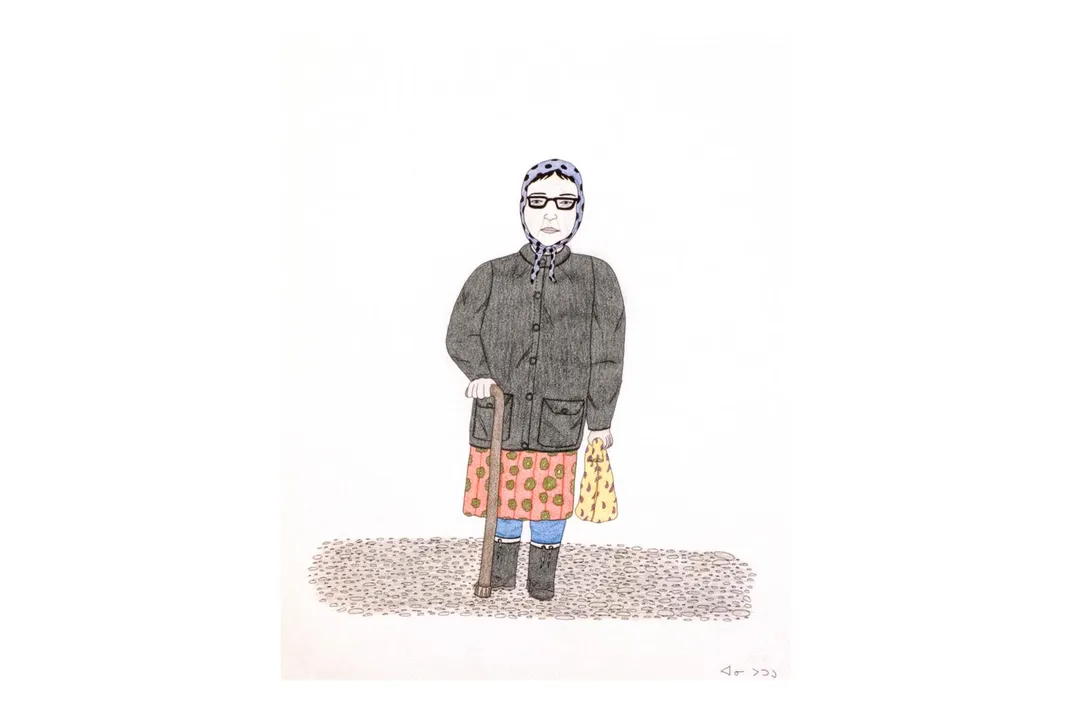

Akunnittinni includes works such as Family Sleeping in a Tent and Watching The Simpsons, which capture how mainstream culture and technology have impacted Inuit life. It also includes a drawing of her grandmother’s glasses, and a portrait of Pitseolak herself. “It captures a very contemporary moment in time,” says Hanley. “There are a lot of different references, but those glasses stand alone in their gracefulness.”

Just three years after releasing her first print in 2003, in quick succession, Annie Pootoogook held a solo exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, She was awarded the Canadian Sobey Art Award, saw her work included in the high-profile Documenta 12 and Montreal Biennale exhibitions, and received numerous other honors. But as her prestige rose, and her impact on Inuit and Canadian art more broadly began to be felt, the artist herself was suffering. By 2016, she was living in Ottawa, selling her drawings for beer money. Her body was found in Ottawa’s Rideau River last September. She was 47 years old.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/84/6c84a305-bc3c-4e89-8fb8-0a8cf385c3d1/pitseolaks_glasses_annie_pootoogook.jpg)

The artist’s tragic death and the wider suffering at the center of many of the works in Akunnittinni pervades much of the show. But while the exhibition does not shy from these painful subjects, ultimately it aims to keep the focus on how the bonds between grandmother, mother and daughter enriched and shaped one another.

“Hopefully people walk away with a new perspective on indigenous women and their lives and livelihood,” says Hanley. “The complexity of these women’s lives coming from such a remote island. This really shows the history and story of indigenous women in Canada, and in general, their struggle and resilience.”

"Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait" runs through January 8, 2018 at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian at the Heye Center in New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/c7/86c7c5ca-4859-4786-9d0a-7fedd0988f4a/pitseolak_ashoona_inuit-3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)