Through the Eye of the Needle: Views of the Holocaust at Ripley Center

A Holocaust survivor’s story is told through a visually stunning new exhibition of fabric art at the S. Dillon Ripley Center

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111128031004krinitz-panel-27-small.jpg)

For years, Holocaust survivor Esther Nisenthal Krinitz sought a way to show pictures to her daughters that told the story of her childhood. At the age of 50, she picked up her needle and began sewing.

“She decided that she wanted my sister and me to see what her house and her family had looked like. She had never been trained in art, but she could sew anything,” says her daughter Bernice Steinhardt. “And so she took a piece of fabric, and she sketched out her home.”

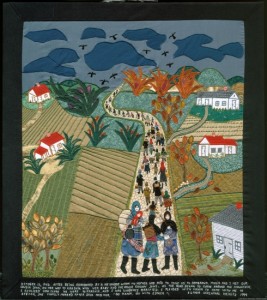

Krinitz stitched her childhood village of Mniszek, near what is today known as Annapol, in rich detail on a large fabric panel, including the Polish settlement’s houses, fields, animals and members of her family. Pleased with the results, she created a companion piece so there would be one for each of her daughters. But as time went on, she couldn’t stop stitching into fabric the images of her childhood, making a new panel for each episode of a story she wanted to tell. Eventually, she would add captions, stitching the words into the works. And over time, she produced works that grew in composition and complexity.

Thirty-six panels later, Krinitz’ story is stunningly visualized at the newly opened “Fabric of Survival” exhibition in the Ripley Center. In the tradition of the graphic novel Maus, Krinitz brings a horrifying story to life in an unidealized, accessible way. The large-scale artworks envelop the viewer, with bold depictions and vivid colors, evoking the emotions of a childhood disrupted by unthinkable trauma.

Krinitz was born in 1927, and enjoyed an idyllic rural childhood until Germany invaded Poland in 1939. “They occupied her village for three years,” Steinhardt says. “In 1942, they ordered all the Jews from the area to leave their homes. They were essentially being deported.”

At the age of 12 15—and somehow aware that complying with Nazi orders could mean certain death—Krinitz decided to take her fate in her own hands. “She pleaded with her parents to think of somebody that she could go to work for, a non-Jew.” says Steinhardt. “She actually left with her sister and they wound up spending the rest of the war under these assumed identities of Polish Catholic girls.” From the entire family, the only members that survived the war were Esther and her sister Mania.

The panels on display document Krinitz’ six-year-long saga as she survived the dangers of concealing her identity under Nazi rule. Many convey the terrors she experienced as a child—in one, German soldiers arrive in the night to her family’s house and force them to line up in their pajamas at gunpoint. In another, Krinitz and her sister are turned away from a friend’s house and spend the night hiding in a pile of farm debris.

But other images capture the boldness and playfulness that Krinitz exhibited even as a child during the Holocaust. Once, while suffering a terrible toothache, she posed as a German child and entered a Nazi camp to have the dentist remove her tooth. Other panels show the simple joys of baking traditional food during Jewish holidays and walking through the fields near her home village.

The works also show Krinitz’ evolving skill, over the years, as an artist. “She created the memory pictures completely out of order, she skipped around,” says Steinhardt. “So you can see the changing design and amount of complexity as you walk through the gallery.” While some of the early works, in terms of date of creation, are more simply designed, the latter ones are incredibly thorough in detail and sophisticated in their composition.

“Fabric of Survival” is especially useful in telling a difficult story to young people. In 2003, Steinhardt and her sister Helene McQuade created Art & Remembrance, an organization that seeks to use art such as Krinitz’ to engage young people in thinking about injustice and oppression. Art & Remembrance uses the works in the exhibition in school-based workshops, where students learn about the Holocaust and illustrate their own stories.

The full set of panels is viewable via a gallery on the organization’s website, but seeing the works in person is a wholly different experience from looking at images online. Up close a remarkable level of detail is revealed—individual stitches represent blades of grass and dozens of villagers can be identified by their distinguishing characteristics.

The story concludes with the final panels, which document Krinitz’ liberation as Russian infantrymen arrived in Poland and her subsequent journey to America. She had planned to make several more pieces to illustrate other anecdotes that occurred during her period of hiding, but was unable to finish the project before she died in 2001 at the age of 74.

Looking through the overwhelming library of fabric art she created, though, one can’t help but feel she completed her mission. “She understood that the world must not forget the Holocaust,” says Steinhardt. “She recognized the power of her pictures to carry her message, and knew that these would be her legacy.”

“Fabric of Survival: The Art of Esther Nisenthal Krinitz” is on display at the Ripley Center through January 29. The world premiere of the documentary based on Krinitz’ story, “Through the Eye of the Needle,” is part of the Washington Jewish Film Festival on Monday, December 5.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)