Time Capsule: A Peek Back to the Day When Elvis Made It Big

On this day in 1956, Elvis appeared on the CBS program, The Stage Show, to skeptical critics and enthused audiences

![]()

Elvis Presley appeared on The Stage Show six times in early 1956, driving his popularity even higher. Shown here on March 17, 1956.

The headline couldn’t have been more dismissive. “Fantastic Hillbilly Groaner is Making a Quick Fortune as Newest and Zaniest Hero of Rock ‘n’ Roll Set.” That was how the Chicago Daily Tribune would characterize Elvis Presley’s performances despite his skyrocketing popularity in the summer of 1956. Even as Elvis-mania was sweeping the country, the critics still weren’t sure what to say about this “hillbilly groaner,” who some labeled as “nothing more than a burlesque dancer.” Still, after a slew of performances on national television, the appeal of the singer was undeniable.

Though it is his September appearance on the Ed Sullivan show that is most widely known now, on this day in 1956—just one day after releasing “Heartbreak Hotel” as a single—Presley began a string of six appearances on The Stage Show on CBS that would mark his debut on the national television stage. He performed three songs, “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” “Flip, Flop and Fly” and “I Got a Woman.” Though Presley had been touring the country for well over a year, it was the first time many had seen the musician in performance.

“Elvis shows up on television,” says music historian Charlie McGovern, who is a senior research fellow at the Smithsonian, “and what does he look like? ‘I don’t look like nobody,’” says McGovern, referencing the young singer’s famous response to a Sun Records employee when asked about his sound.

McGovern, who helped curate the exhibit, “Rock ‘n’ Soul: Social Crossroads,” on view in Memphis, Tennessee, says Presley was able to hit on every nerve of post-war America. Television in particular served to electrify his unconventional image, despite the fact that many in the television world were critical of, and even openly mocked, his sound and popularity.

Sun Records Studio where Elvis Presley got his break. Photo by Carol Highsmith, courtesy of the Library of Congress

“Elvis makes his first recordings in early July of 1954. Literally as Brown v Board is becoming law of the land, he’s in the studio in effect doing a different kind of integration,” explains McGovern. Starting out at Sun Records in Memphis, Presley worked with Sam Phillips, known for recording blues artists like Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. Phillips cut somewhat of an unusual figure in Memphis, says McGovern, for his appreciation of black musicians and black music. “A lot of the black artists found their way to Sam or he found his way to them, before he ever played the white kids like Elvis Presley.”

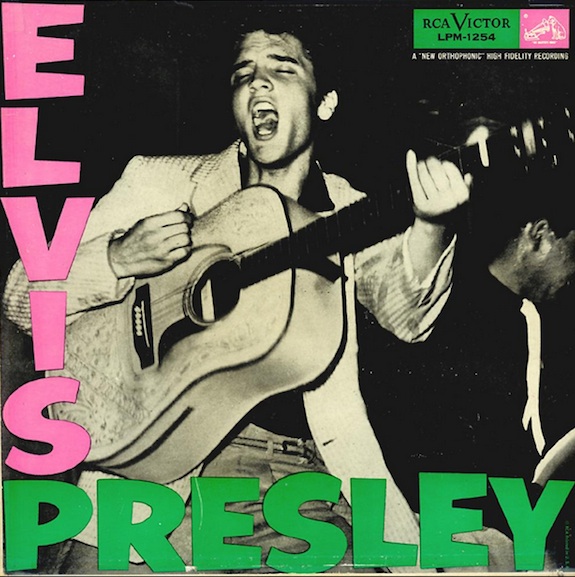

But being on a regional label meant distribution was a challenge. A hit could often put a small company further back than a flop, explains McGovern, because the capital to ramp up distribution simply wasn’t available. Presley toured the south and into the north and eventually, in late 1955, he signed with the national label, RCA Victor, for an unprecedented $40,000. Now with a major label, Elvis began a television tour that would formally introduce him to the country, whether they were ready for it or not.

“Television in 1956 has reached a great number of American homes,” says McGovern. “By the end of the decade, more than 90 percent of American homes have television as compared to a pretty small percentage in 1948 when it’s really first introduced.” Being able to get a gig on the Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show represented a whole new level of visibility for the singer, one that his manager, Colonel Tom Parker made sure to manage carefully. “Getting Elvis on television gets him exposed to more people than he could have done with live performances, and it enables Parker and his folks to package Elvis in a certain way as a kind of product.”

Being on a national label elevated Elvis mania to new highs. Courtesy of the American History Museum

With his background in carnivals, circuses and live performance, Parker understood balancing saturation and demand. McGovern says, “The old-school carnie-type entertainers are all about leaving the audience wanting more, you promise more than you give so that they come back.”

True to Parker’s mission, the audience could not seem to get enough. The critics, on the other hand, had had quite enough. Even the house band on The Stage Show greeted Presley with skepticism as an unschooled, unkempt kid.

“He’s primarily a hip-tossing contortionist,” wrote William Leonard in the Chicago Daily Tribune. Leonard called the reaction Presley inspired in young girls, “sheer violence.” Noting his flamboyant fashion–shirts and pants of every shade that often prompted people to remark, “You mean you can buy stuff like that in regular stores?”–Leonard continued, “He’s young and he sings, but he’s no Johnnie Ray and he’s no Frank Sinatra.”

Much of the criticism centered on Presley’s ambiguous cultural status. “In the mid-1950s, what are Americans worried about,” asks McGovern, “They’re worried about juvenile delinquency; this is a country now awash with kids but the demands on those kids have changed. They’re worried about sex; this is tied to delinquency. And in many places, they’re worried about race and the prospects of integration.” Presley came to represent all of these concerns with his dancing, mixing of genres and styles. “His singing registers black, his dance moves register sex and he’s Southern and there’s a kind of gender ambiguity about him.”

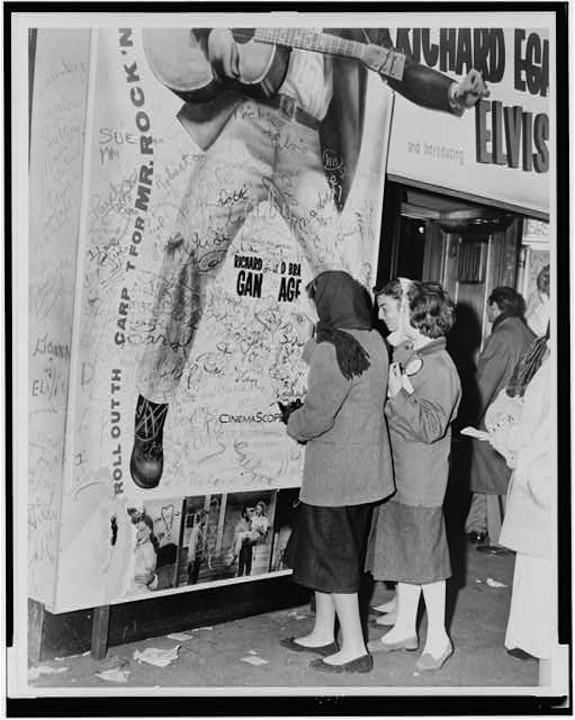

Teenage girls add to graffiti on bottom of Elvis movie poster. Photo by Phil Stanziola, 1965, courtesy of the Library of Congress

As odd as it was to critics, his appearance and identity resonated with many Americans. After the large internal migrations of the Dust Bowl, the Great Migration and the post-war integration of returning soldiers who had served with people from around the country, there was a new visibility of regional cultures. With the rise of a leisure class, Americans and so-called protectors of taste began to worry about how people would fill their time.

Nonetheless, after his six appearances on CBS, other programs knew they needed to get in on the Elvis phenomenon, even prompting Ed Sullivan to book him despite his belief that he was unfit for family viewing. It was only after Steve Allen beat him to the punch on NBC and beat him in the ratings that Sullivan reconsidered.

Even as they clamored to get him on their shows, hosts like Allen didn’t quite know what to do with Presley, says McGovern. “He puts him in top hat and tails and makes him sing Hound Dog to a basset dog,” McGovern says. “If you think about it, it is so contemptuous and so freaking degrading.”

“They’re all making fun of this thing that none of them really understand and none of them, least of all Elvis, feel that they’re in control of,” he says.

“When Elvis tells Sam Phillips, I don’t sing like nobody else, he wasn’t bragging, as much as I think he was sort of stating pretty accurately that what he sang represented gospel music, white and black, it represented country music, blues music he had heard and it represented pop music.”

For more about Elvis Presley, including his appearance on the Stage Show, check out Last Train to Memphis by Peter Guralnick.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)