Tokyo in Transition: Woodblock Prints Cast an Ambiguous Light on Japan’s Modernization

A collection of works by the great Eastern modernist Kobayashi Kiyochika are on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum

In the artwork, “Sumida River by Night,” a man and a woman stand on a shoreline, shrouded by twilight, in 19th- century Japan. Their silhouettes are dark against the rippling water as they stare across its depths at the vanishing city of Edo, already well on its way toward becoming a bustling, modernized Tokyo. The female, a geisha, wears flowing robes and a traditional hairstyle. Her companion, however, is outfitted in Western apparel; a bowler hat is perched on his head, and his suit’s sharp angles cast the aura of a worldly gentleman. Is the man’s garb a sign of sophistication? Or is it a cynical sign that he’s “trying on” a foreign identity that’s not really his own?

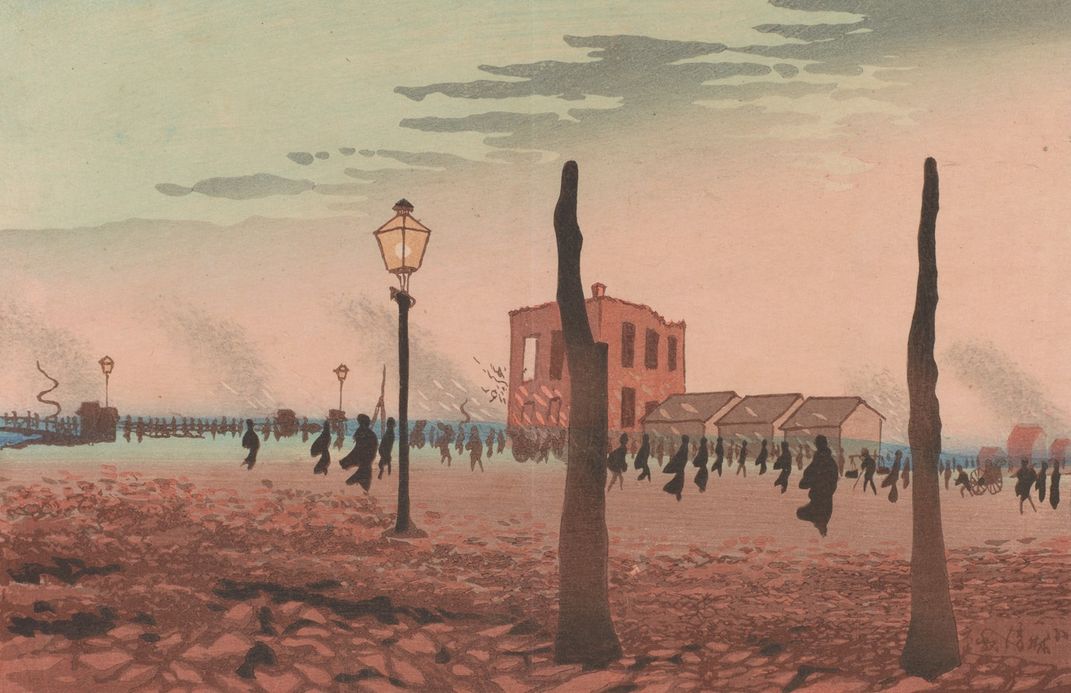

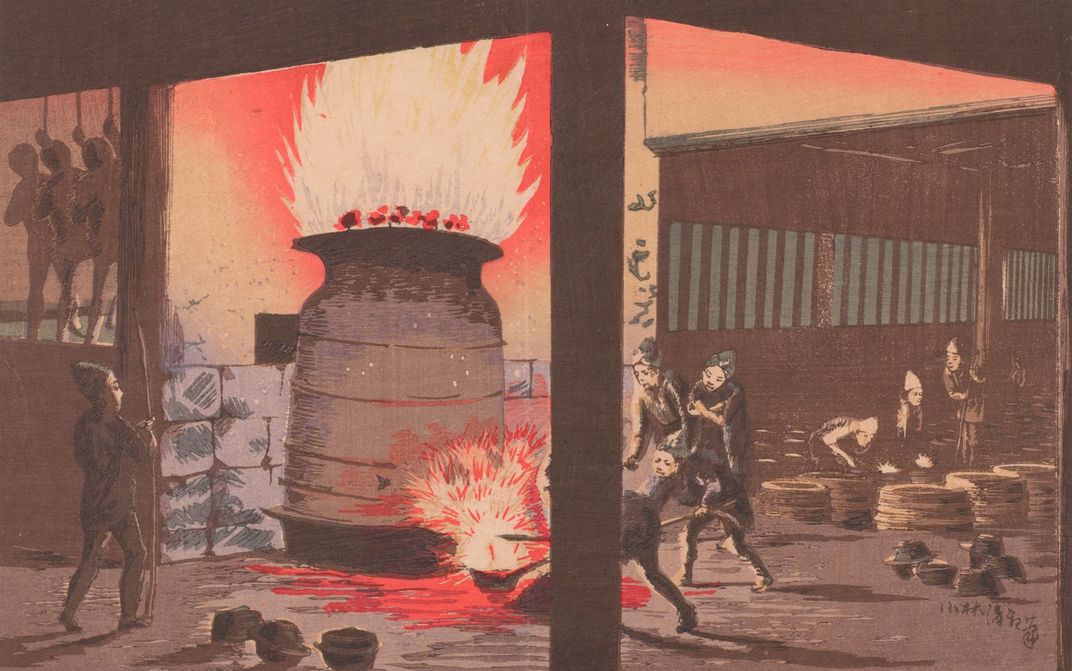

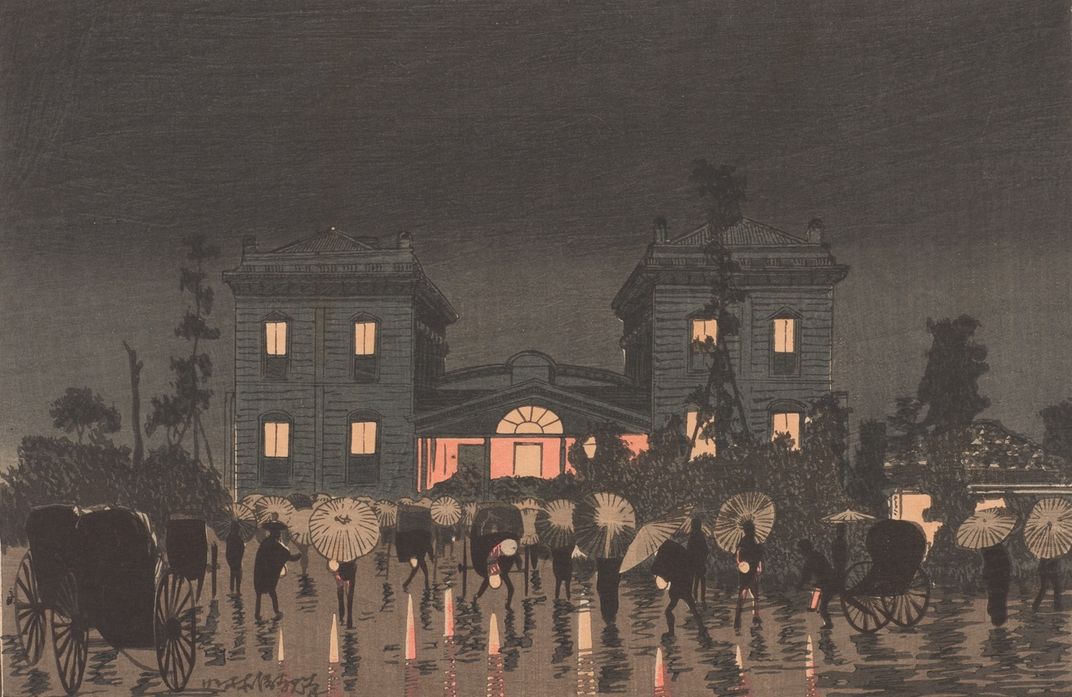

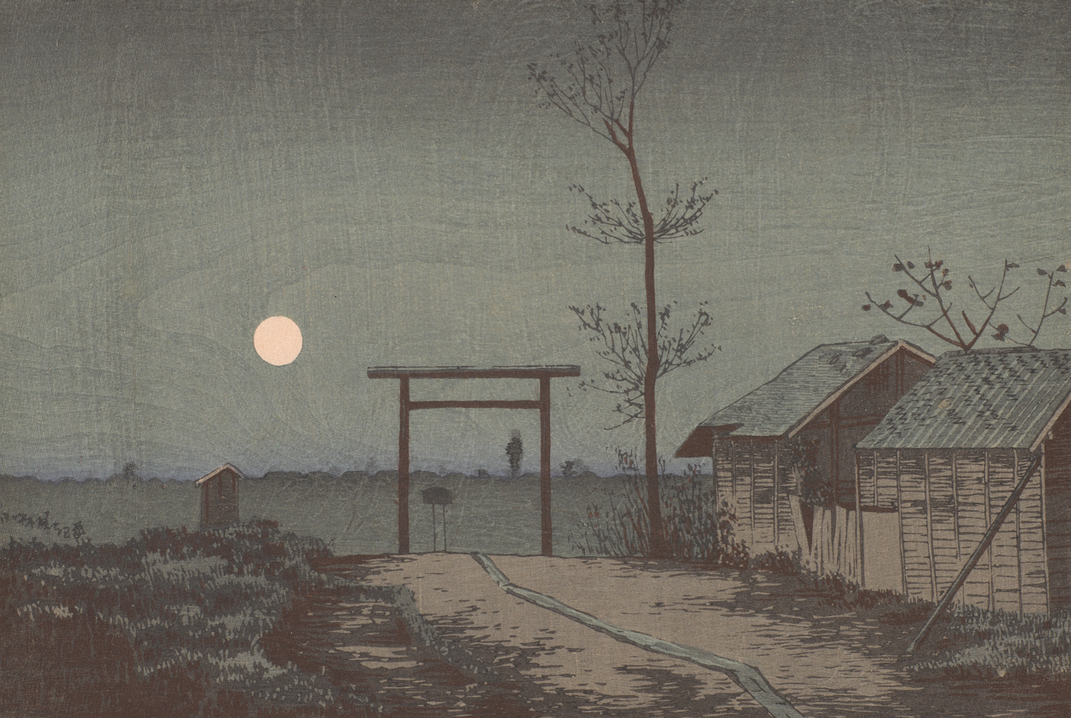

Created by Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), whose work primarily depicts the atmospherics and happenings during the dusk and dawn of the day, this woodblock print is featured along with more than 40 of the artist's urban landscapes in the current exhibition, “Kiyochika: Master of the Night.” Kiyochika’s woodblock prints have been described as “studies in shadow and light”—a dichotomy that suits the artist, who is often described as both Japan’s last great woodblock print master and one of its first great modernists. The artist's works are also ambiguous in mood and intent. “You don’t know whether he’s excited and praising [his modernizing surroundings], or being sardonic,” says James Ulak, a curator at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

Kiyochika came of age during the fall of the shogun and the rise of the Emperor Meiji. A son of a minor government official, the young Kiyochika was exiled from his birth city, Edo, during the country’s civil war. Rechristened “Tokyo,” or “Eastern Capital,” Edo transformed from a sleepy feudal outpost into an industrial capital teeming with horse-drawn carriages, gaslights and telegraph lines. Six years later, Kiyochika came home to his old city—and a new world. “You could probably almost say it was a Rip van Winkle moment,” says Ulak. “He walked in, and all these changes were happening. How do you memorialize them? How do you visualize them?”

Little has been recorded about Kiyochika’s life, but scholars believe that he was a self-taught artist who dabbled in photography, printmaking and Western-style and traditional painting. So in response to his country’s rapid modernization, Kiyochika set out to record the changes in Tokyo in a series of woodcuts unlike any seen before in Japan.

While most woodcuts were celebratory and colorful, Kiyochika’s were moody and dark. They featured Japanese imagery, but also incorporated crosshatching and other techniques that appear to have been influenced by Western lithographs. Most importantly, though, many of the woodcuts depicted the introduction of new innovations, like railroads, brick buildings and block towers. The artist’s sense of wonder is palpable, as is his unease.

“Kiyochika was as curious as he was pessimistic,” says François Lachaud, a professor of Japanese Studies at the French School of the Far East in Paris who helped curate “Kiyochika: Master of the Night.”

“He learned Western techniques of representation, not to celebrate the famous sites of the new capital, but to question modern bureaucratic aesthetics.”

The woodblock prints portray a country on the precipice of historic change. But they aren’t condemning; just observant. “If Kiyochika was a man of strong political convictions, he never was, nor intended to be, a ‘political artist,’” says Lachaud.

Kiyochika aspired to create 100 prints, but his plan was cut short by two large fires that obliterated much of Tokyo in 1881. Kiyochika’s studio burned down; after completing 93 images in his series, he returned to a more traditional style of art. By then, however, he’d become Japan’s first transnational artist, and had invented a new way to represent the country’s modern industrial centers.

“Traditionally, the whole idea of cityscapes in Japanese art was to celebrate something—for example, the rebirth of a city after an earthquake or a fire,” says Ulak. “Sometimes what was depicted was not necessarily true to fact. In Kiyochika’s series, he’s showing Tokyo like he sees it. It’s not a documentary take; it’s an interpretive one.”

"Kiyochika: Master of the Night" is on view daily, 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., through July 12, at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1050 Independence Ave. SW.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)