The Topsy-Turvy Worldview of Georg Baselitz

Upside-down paintings are part of a 60-year survey of the German painter and sculptor, who makes a return to the Hirshhorn

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/c2/b6c2e32c-d41f-4c28-a38e-a6f5dc727ba7/gb_m_2006_07_25.jpg)

Encountering the first upside down figure in the massive retrospective of German artist Georg Baselitz may seem at first to an unaware visitor to be an installation lapse. But walk a little farther into Baselitz: Six Decades at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, and the inverted figures begin to multiply.

There are enough such canvases—dozens—amid the more than 100 works in the show, his first major U.S. survey in 20 years, to begin to create a topsy-turvy world view.

A working artist since the late 1950s in Berlin, Baselitz was heavily influenced by the freeing expressionism of Willem de Kooning after seeing a traveling U.S. exhibition there. The artist first drew widespread attention with his army of upside downs in the 1970s. All along, it’s been more than a matter of inverting canvases, says Stéphane Aquin, the Hirshhorn curator who helped organize the survey.

“To all the questions that you may have,” Aquin begins with, as he walks through the exhibition, “Baselitz paints like this. He does not paint them right side up and turn them upside down. He paints them upside down.”

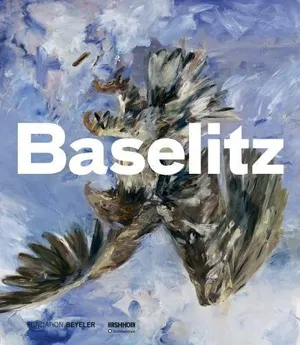

Georg Baselitz

On the occasion of the 80th birthday of Georg Baselitz (born 1938)―one of the most influential painters and sculptors of our time―the Fondation Beyeler is devoting an extensive retrospective to the artist, gathering many of Baselitz’s most important paintings and sculptures from the past six decades for the first time.

Using photographs as a model, he finds a new way to perceive the figure, Aquin says. In doing so, “he defeats the purpose of iconography by inverting the image.”

“Turning the motif upside down gave me the freedom to tackle the problems of paintings,” Baselitz once said.

It was a method to further distance him from reality, according to the show’s wall text, “reducing the images to the base formal qualities of line, shape and color.”

First seen in 1969 on a variation of a 19th-century landscape by Ferdinand von Rayski, the inverted images of Baselitz raised his profile. It’s an approach to which he has returned in recent decades. But as the show makes clear, the German expressionist has had a knack of getting attention since his earliest days.

Indeed, his very first artwork received front page headlines when German authorities confiscated his 1962 painting The Naked Man for obscenity. “Baselitz’ career starts with major, major scandal,” Aquin says. “And it has sort of defined his career to be always against systems, against authority, against any forms of imposed order.”

As a young artist raised in East Germany, he learned about freedom and flouting authority from a traveling exhibition of American expressionism that came to Berlin in 1958. “The power of that exhibition was incredible,” Baselitz says through an interpreter at a Hirshhorn artist’s talk. “The most important artist was [Jackson] Pollock—he was already dead, but he was towering over everything. But the other artist that made a big impression was De Kooning.” The freedom of De Kooning’s brush stroke left an impression in the bold strokes Baselitz would also use. But at the same time, he was determined to forge his own course.

After shaking up the German art world with his first show, he did a series of portraits, “Heroes,” that put the German experience in context before he began his topsy-turvy phase.

He was asked to come to the U.S. after his monumental three-dimensional wooden work, Model for a Sculpture, the sole representative of Germany in the 39th Venice Biennale in 1980 got a lot of attention (again for the wrong reasons: some thought the figure with an upraised hand was doing a Nazi salute).

But it was the sight of six upside down Baselitz canvases at the 2015 Biennale that led to the current exhibition, Aquin says. “It was striking to see this man who was there [so long ago] come up with strong, strong works.”

“I knew Baselitz’ work and had followed his influence on American painters in the 1980s,” says Hirshhorn director Melissa Chiu. “But here was an artist who was painting on such a scale and with such an attention to humanity that it was time to review his work.”

In fact, his last major U.S. survey, organized by the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1995, traveled to the Hirshhorn in 1996. The current show, though, covers half again as many years of work, with many of the pieces painted in the last 20 years and receiving their first appearances in the U.S. Baselitz may still be best known for being such a direct inspiration for the New York painter Jean-Michel Basquiat. Aquin calls his inverted 1981 series Orange Eater “Basquiat before Basquiat.”

Baselitz never accepted the connection. Still, getting that Guggenheim retrospective in 1995 “was like being in heaven,” he says. With the new Hirshhorn exhibition, he added, it is a feeling “that has continued until today.”

Baselitz: Six Decades, curated by Stéphane Aquine with the assistance of Sandy Guttman, continues through September 16, 2018 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)