A Scholar Follows a Trail of Dead Mice and Discovers a Lesson in Why Museum Collections Matter

A former Smithsonian curator authors a new book, Inside the Lost Museum

:focal(1139x478:1140x479)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/0c/160c0158-4e53-4457-8dd7-5701e6620440/newcropdsc9951.jpg)

The big jar of mice stopped me cold. John Whipple Potter Jenks had collected these mice 160 years ago. He had probably followed Spencer Baird's 1850 instructions: keep a small keg handy, partially filled with liquor, and throw the mice in alive; this would make for “a speedy and little painful death” and “the animal will be more apt to keep sound.”

The mice had been transferred to a new jar and they had been retagged. But here they were. I had been following Jenks’ trail for several years, and suddenly felt that I was, oddly, in his presence.

On September 26, 1894, naturalist, taxidermist, popular science writer and beloved professor John Wipple Potter Jenks died on the steps of his museum at Brown University. "He had lunched, perhaps too heavily, . . . and expired without a moment's sickness or suffering," one of his students would write.

The Jenks Museum offered students and local visitors glass cases packed with taxidermied animals, ethnographic items from around the world, and other museum-worthy "curiosities"—some 50,000 items. But even before his death the museum had come to seem old-fashioned.

Brown University closed the museum in 1915 and discarded most of its collections in the university dump in 1945. For many years I was a museum curator at the Smithsonian. Now, I'm a professor of American studies at Brown, and the mostly forgotten Jenks Museum has long fascinated me. I've made it the framework of my new book, Inside the Lost Museum. Through the lens of Jenks' lost museum, my book details the valuable work that goes on in museums today: collecting, preserving, displaying, and studying art, artifacts and natural history specimens.

In 1850, when the Smithsonian Institution issued a call for natural history specimens—in particular for “small quadrupeds, as field mice, shrews, moles, bats, squirrels, weasels”—Jenks was one of many naturalists who responded. He sent Baird (who would later become the Institution's second secretary) hundreds of mice, voles, shrews, weasels, muskrats and skunks, along with one rat and two foxes.

“I interested my pupils and others to bring them into me till he cried enough,” Jenks wrote in his autobiography. (Jenks paid them six cents per mouse.)

Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present

In this volume, Steven Lubar, among the most thoughtful scholars and professionals in the field, turns "museum" into a verb, taking us behind the scenes to show how collecting, exhibiting, and programming are conceived and organized. His clear, straightforward, and insightful account provides case studies as well as a larger framework for understanding museological practices, choices, historical trends, controversies, and possible futures. The treatment of art, science, and history museums and occupational roles from director and curator to exhibition designer and educator make this required reading for everyone in the museum field.

The Smithsonian’s Annual Report thanked him for his work: “One of the most important contributions to the geographical collections of the institution has been the series of mammals of eastern Massachusetts received from Mr. J. W. P. Jenks of Middleboro.”

Baird analyzed the specimens he received for his 1857 compendium, The Mammals of North America: The Descriptions of Species Based Chiefly on the Collections in the Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

When Baird finished looking at and measuring Jenks’ “varmints,” they were stored at the Smithsonian along with all of the other animals Baird had used for his Mammals.

They were also made available for other scientists to use for their work.

In 1866 Joel Asaph Allen, a curator at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), began work on his Catalogue of the Mammals of Massachusetts. This 1869 catalog was based mostly on Allen’s own collecting in Springfield, but Allen knew about Jenks’ collections at the Smithsonian from Baird’s book, and he wanted to examine them.

On June 24, 1866, the Smithsonian shipped them to the MCZ, not too far from their first home in Middleboro, for Allen to work on. Allen learned new things from Jenks’ mammals and offered this appreciation of his work: “No one has done more to increase our knowledge of their history than Mr. J. W. P. Jenks, of Middleboro.”

Jenks’ mice would continue to show up in taxonomic texts, but they would also serve another purpose. In February 1876 the MCZ received a shipment of rodents from the Smithsonian, among them several of Jenks' specimens. In its role as the national museum, the Smithsonian distributed identified sets of specimens like these to museums across the country. Jenks’ mice found new homes at, among other places, the University of Michigan, the Chicago Academy of Sciences, and Women’s College, Baltimore (now Goucher College).

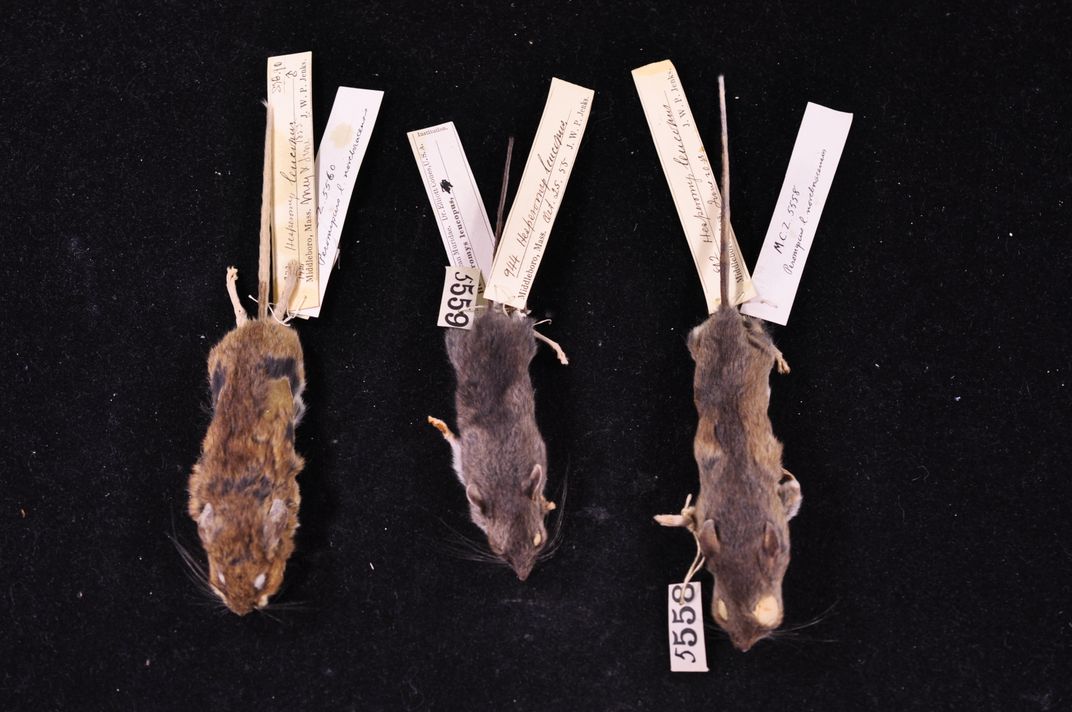

Jenks’ mice were useful. Scientists examined them and measured them—a dozen or more measurements for each mouse—built taxonomies with them, and used them in other types of research. That’s why they were collected, and that’s why they have been preserved. Many of Jenks’ mice are still at the Smithsonian and the MCZ and other museums across the country, awaiting further use. I wanted to see them. That's when I found the large jar at MCZ.

Jenks’ mice tell a traditional story of scientific collections. They weren’t collected for display, have never been on display, and probably never will be. Neither will 99.9 percent of the world’s 3 billion natural history specimens.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/14/5f14af10-31e7-49d2-a8b2-a9afedda5a59/lubarfig0401web.jpg)

But that doesn’t mean they aren’t useful. Look behind the scenes, and you see them put to use.

Anthropologist Margaret Mead led a virtual tour of the American Museum of Natural History in her 1965 Anthropologists and What They Do.

“Up here, on the curators’ floor, the long halls are lined with tall wood and metal cabinets and the air has a curious smell—a little stale, a little chemical—a compound of fumigating substances and mixed smells of actual specimens, bones, feathers, samples of soils and minerals,” she wrote. You might get the idea that a museum is “a place filled with specimens smelling of formaldehyde, all rather musty and dated and dead.”

But then you open a door into a curator’s office: “A curator’s office is a workshop. Here he spreads out new specimens to catalogue or old ones to study. Here he makes selections for exhibits, comparing his field notes and his field photographs with objects collected on a recent field trip or perhaps a half-century ago.” The researcher gives the specimen new life.

Richard Fortey, a paleontologist at London’s Natural History Museum, leads us on another behind-the-scenes tour. He shows us “the natural habitat of the curator,” the “warren of corridors, obsolete galleries, offices, libraries and above all, collections.”

There are endless drawers of fossils, arranged taxonomically, like the mammals at the MCZ. Each is labeled with its Latin name, the rock formation from which it was recovered, its geological era, location and the name of the collector, and, sometimes, where it was published. This is where Fortey does his work, assigning names to new species, comparing examples to understand systematics (the relationships between species), and generalizing about evolution and geological and climate change. “The basic justification of research in the reference collections of a natural history museum,” writes Fortey, “is taxonomic.”

Natural history collections have been the basis of the most important biological breakthroughs from Georges Louis Leclerc Buffon’s 1749 Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière to Georges Cuvier’s theories of animal anatomy in the early 19th century, and from Darwin’s 1859 theory of evolution to Ernst Mayr’s mid-20th-century evolutionary synthesis.

Gathering together and ordering specimens in museums made it easier to learn from them. It became simpler to compare and to build theories from them. “How much finer things are in composition than alone,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson after a visit to the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in 1833. Emerson saw there “the upheaving principle of life every where incipient,” the organization of the universe.

Similarly, scientists could find principles of organization useful to their work. Science historian Bruno Strasser writes, “When objects become accessible in a single place, in a single format, they can be arranged to make similarities, differences, and patterns apparent to the eye of a single human investigator; collections concentrate the world, making it accessible to the limited human field of view.” As Buffon put it in 1749, “The more you see, the more you know.”

Collecting for scientific ends has always been central to American museums. The goal of Charles Wilson Peale’s Philadelphia museum, established in 1786, was the promotion of useful knowledge. That was also the goal of the nearby American Philosophical Society, the Smithsonian when it was founded in 1846, and of natural history museums across the United States in the 19th century. They built collections for researchers. They published volumes of scientific papers. Outreach—exhibits, lectures, popular education—was a secondary goal for much of their history.

Taxonomy and systematics—the identification and classification of plants and animals—was, until the 20th century, the most important work of biology, and put natural history museums at the center of the field. Taxonomy, explains Harvard’s Edward O. Wilson, another denizen of the museum storeroom, “is a craft and a body of knowledge that builds in the head of a biologist only through years of monkish labor. . . . A skilled taxonomist is not just a museum labeler. . . . He is steward and spokesman for a hundred, or a thousand, species.”

But by the middle of the 20th century, biology based in the museum seemed less important than biology based in the laboratory. Experimental and analytical sciences—genetics, biochemistry, crystallography, and eventually molecular biology—made natural history seem old fashioned.

Function seemed more important than form, chemistry more important than taxonomy, behavior more important than appearance. Collections were out of fashion.

The museum biologists fought back. Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology was one of the places this battle—Wilson called it “the molecular wars”—was fought. He wrote: “The molecularists were confident that the future belonged to them. If evolutionary biology was to survive at all, they thought, it would have to be changed into something very different. They or their students would do it, working upward from the molecule through the cell to the organism. The message was clear: Let the stamp collectors return to their museums.”

Bruno Strasser points out that the natural historians who worked in museums had always collected more than just specimens of animals and plants. They had also collected, starting in the 19th century, seeds, blood, tissues and cells. More important, they had also collected data: locations, descriptions, drawings.

All those measurements of Jenks’ mice were part of a vast database that included not just the collection of skins and skeletons but also information about the creatures.

This proved useful for answering new questions. Joseph Grinnell, founding director of Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, emphasized the importance of this data for the new biology of the early 20th century: “The museum curator only a few years since was satisfied to gather and arrange his research collections with very little reference to their source or to the conditions under which they were obtained. . . . The modern method, and the one adopted and being carried out more and more in detail by our California museum, is to make the record of each individual acquired.”

Grinnell’s California collection included not only 100,000 specimens but also 74,000 pages of field notes and 10,000 images. “These field notes and photographs are filed so as to be as readily accessible to the student as are the specimens themselves.”

Grinnell thought that this data might end up being more important than the specimens.

When scientists like Wilson became interested in theoretical questions of population ecology in the 1970s, the collections and the data about them proved essential. When issues of pollution and environmental contamination became important in the 1980s, or climate change in the 2000s, the collections were useful.

Museums have pivoted from a focus on systematics to biodiversity as they look for new ways to take advantage of their hard-won collections. Biodiversity research relies on systematics; you can’t know what’s going extinct unless you know what you have.

The 1998 Presidential Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystems called for digitizing collections data as a vital first step—a call that was answered over the next 20 years with systems like the ones that allowed me to find Jenks’ mice scattered across the country.

Over the past decade there have been many arguments for the practical value of natural history collections. Collections are useful in tracking invasive species as well as documenting, for example, the presence of DDT (measuring the thickness of eggs from museum collections) and mercury contamination (using bird and fish specimens). Collections are useful in the study of pathogens and disease vectors; millions of mosquito specimens collected over the course of a century provide information on the spread of malaria, West Nile virus and other diseases. The invasive Asian long-horned beetle was identified from a specimen in the Cornell entomology collections.

The molecular revolution of the 2000s unlocked even more information from the collections. It’s possible to extract DNA from some specimens, not only to improve taxonomy but also to learn about diseases and even the evolution of viruses.

Researchers have used material from collections to trace the history of the 1918 influenza virus. An analysis of the 1990s hantavirus outbreak using museum rodent collections was useful to public health officials in predicting new outbreaks—and researchers argue that had there been good collections from Africa, the recent Ebola outbreak would have been easier to understand and control.

Natural history museums continue to serve as what the director of the Smithsonian's U.S. National Museum once called a “great reference library of material objects.” Pulled from across time and space, they pose—and answer—old questions and new.

<style type="text/css">p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 16.0px Georgia; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 16.0px 'Times New Roman'; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000} span.s1 {font-kerning: none} </style>

Extract adapted from Inside the Lost Museum by Steven Lubar, published by Harvard University Press, $35.00. Copyright © 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.