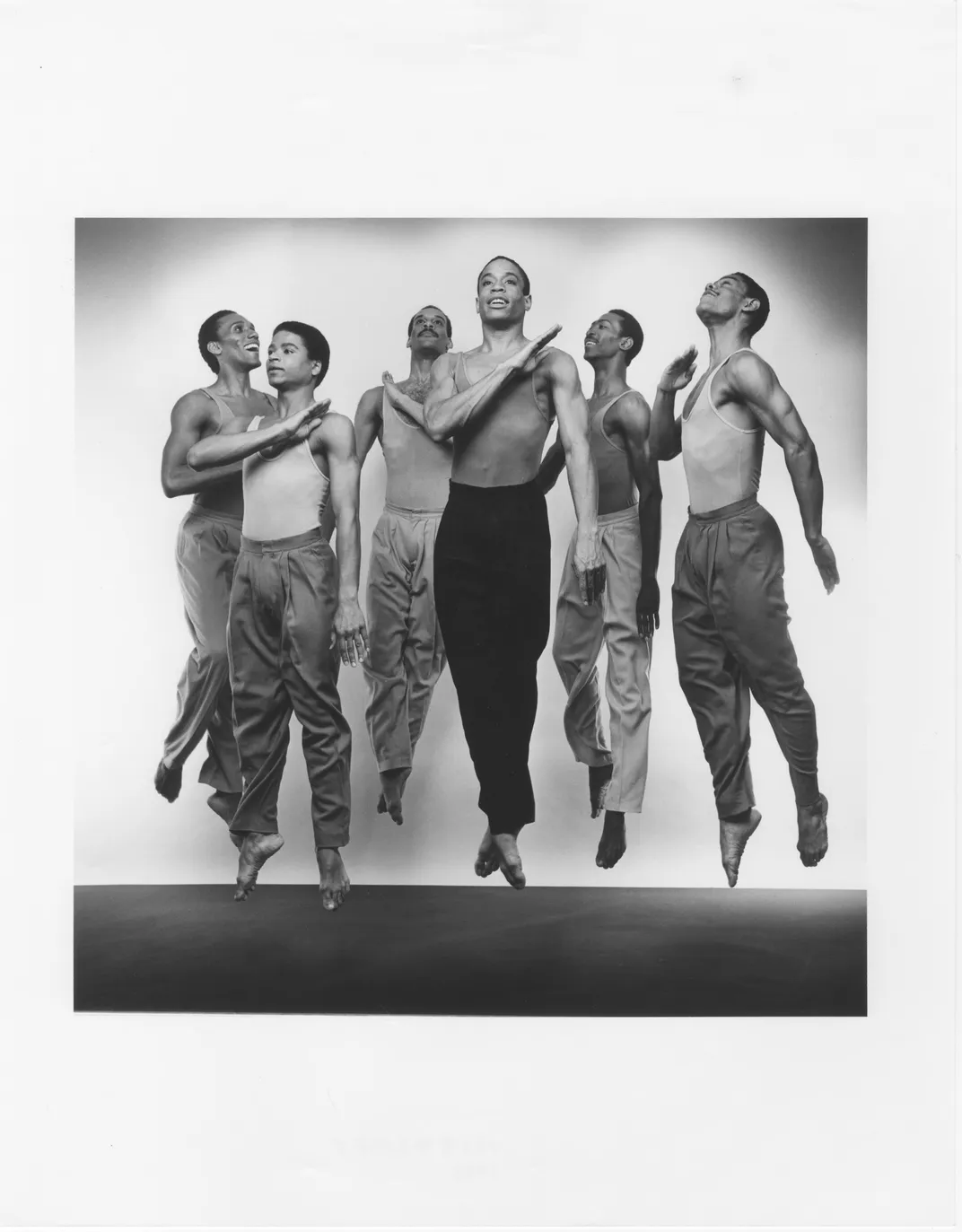

Modern dance impresario Alvin Ailey once asked photographer Jack Mitchell to shoot publicity images of his dancers for their next performance without even knowing the title of their new work. Seeing “choreography” in the images Mitchell produced, Ailey leapt into an ongoing professional relationship with Mitchell.

“I think that speaks to the trust that they had in one another,” says Rhea Combs, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Ailey “knew it would work out somehow, some way.”

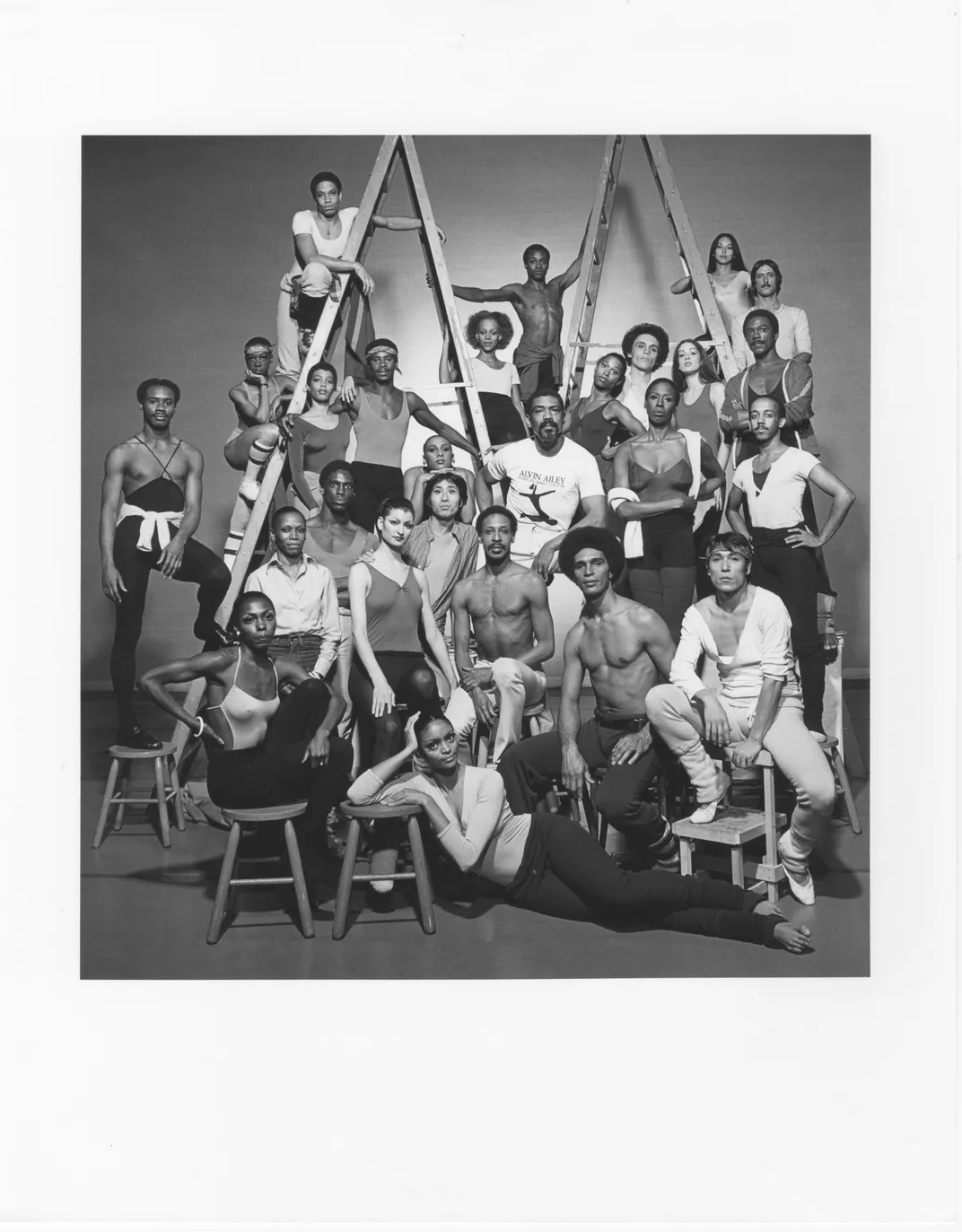

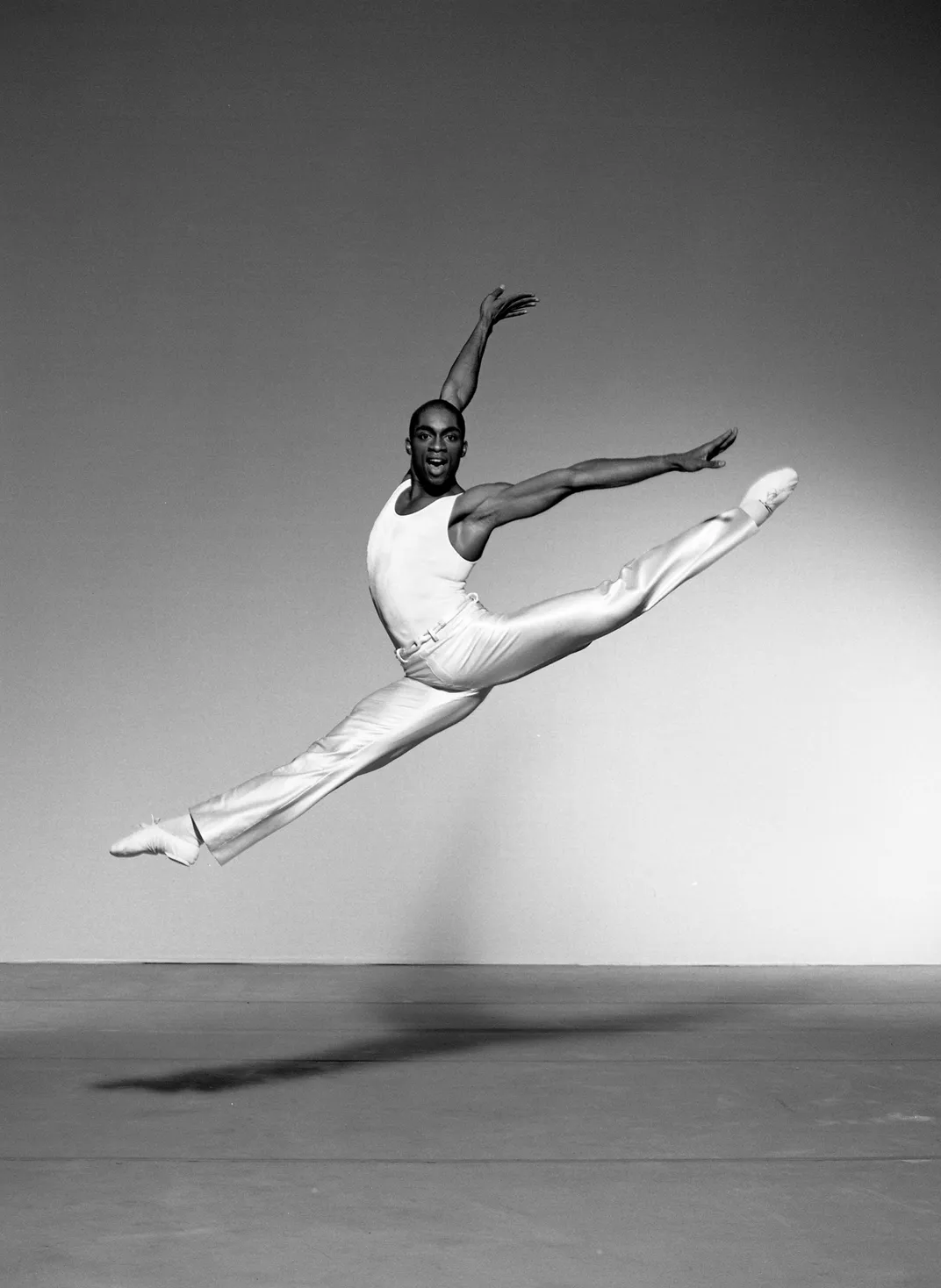

This partnership, which began in the 1960s, led to the production of more than 10,000 memorable images, and the museum has now made those photos available online. The Jack Mitchell Photography of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection allows viewers to see 8,288 black-and-white negatives, 2,106 color slides and transparencies, and 339 black-and-white prints from private photo sessions. The collection became jointly owned by the Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation and the museum in 2013. Afterwards, the museum began the tedious effort to digitize, document and catalogue the images.

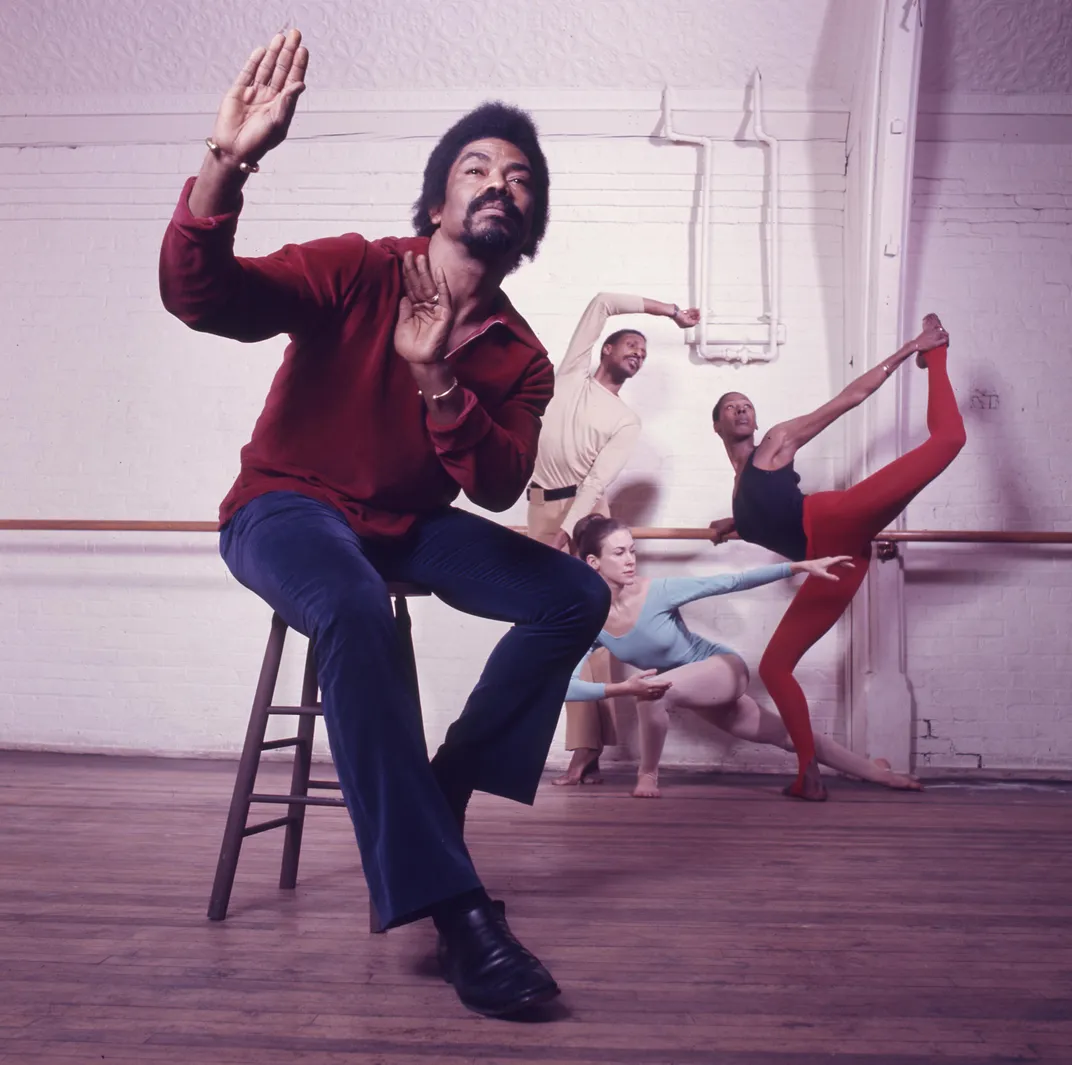

The partnership between Ailey and Mitchell was consequential for Ailey’s career: Biographer Jennifer Dunning, writes that Mitchell’s work “helped to sell the company early on.” Combs believes that is true. “Ailey was not only an amazing dancer and choreographer . . . .He had to be an entrepreneur, a businessperson,” she says. In other words, he had to market his work.

This was a partnership between two artists at the “top of their game,” Combs notes. The fact that “they found a common language through the art of dance is really a testament to the ways in which art can be used as a way of bringing together people, ideas, subjects and backgrounds . . . in a very seamless and beautiful way.”

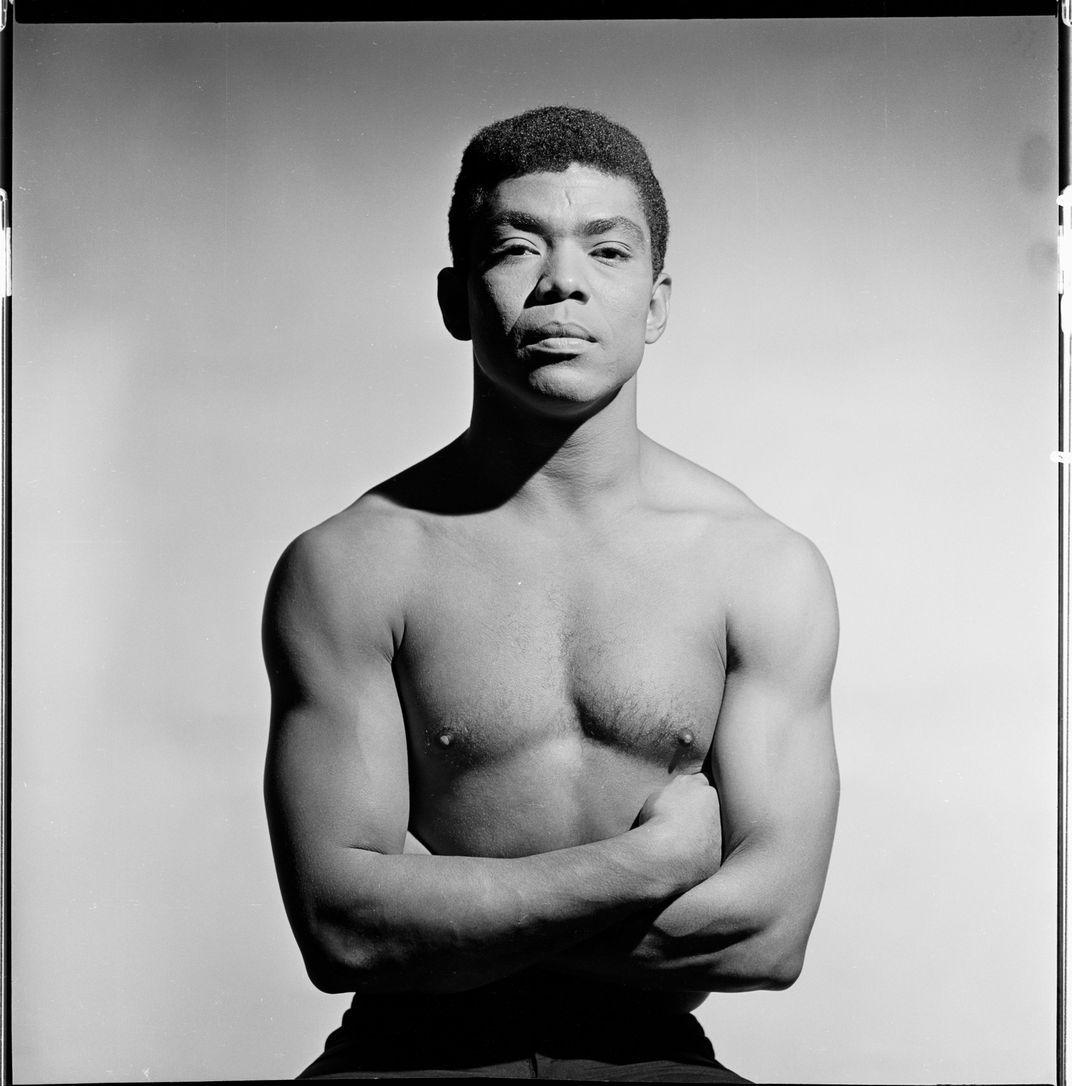

Alvin Ailey spent the early years of his childhood in Texas before moving to Los Angeles, where he saw the Ballet Ruse de Monte Carlo perform and begin considering a career in dance. He studied modern dance with Lester Horton and became part of Horton’s dance company in 1950 at the age of 19. After Horton’s sudden death in 1953, Ailey moved to New York, where he made his Broadway debut in 1954’s House of Flowers, a musical based on a Truman Capote short story. The show boasted a wealth of African American talent, including actress and singers Pearl Bailey and Diahann Carroll.

Ailey established the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1958. Beginning as a dancer in his own company, he gradually diminished and eventually ceased his own performances to make more time for choreographing programs. As a New York Times reporter wrote in 1969, “four years ago, Ailey, then 34, a daring young man stepping off the flying trapeze switched from tights to tuxedo to take his opening night bow.” For Ailey, choreography was “mentally draining,” but he said that he found rewards in “creating something where before there was nothing.”

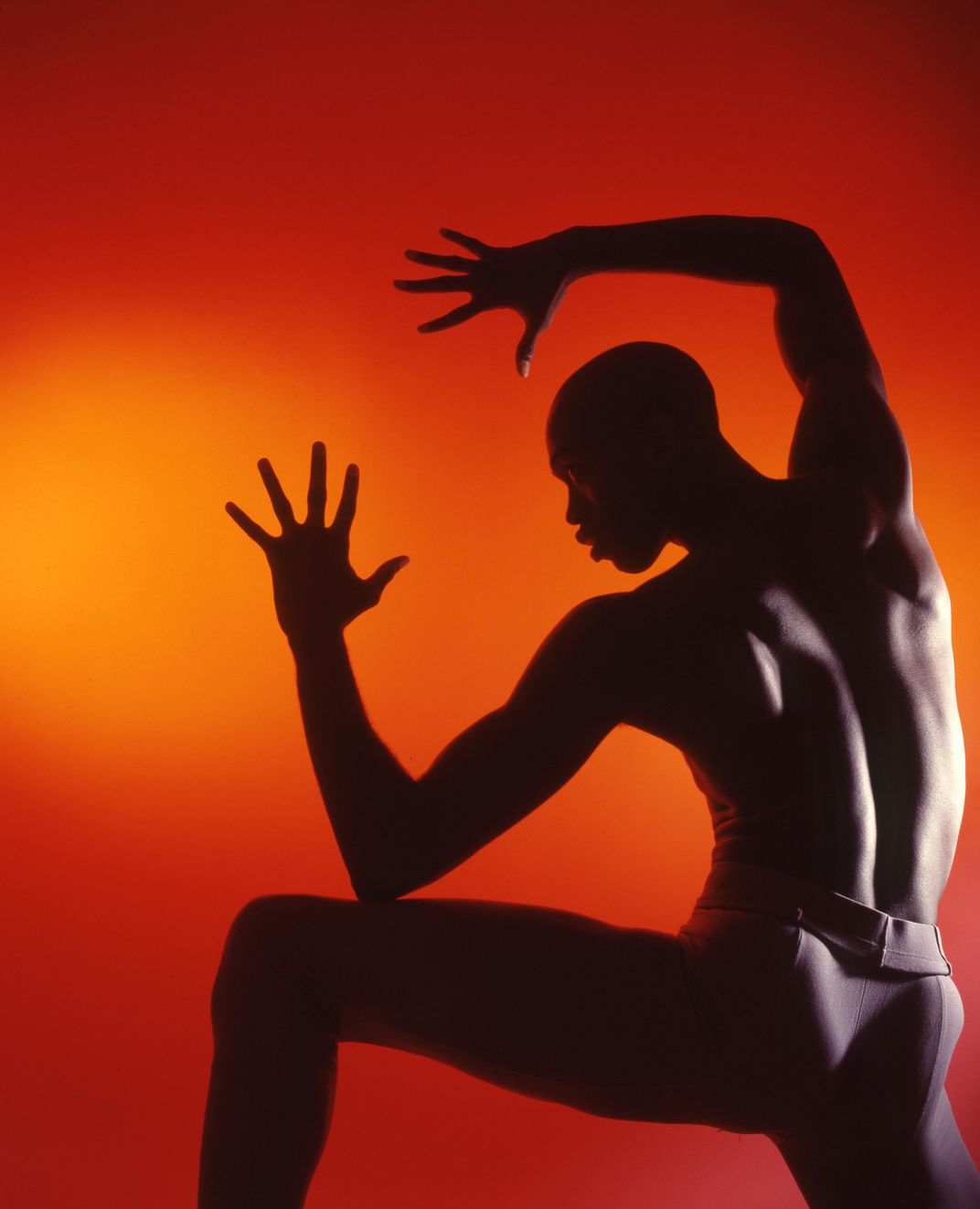

Combs says Ailey was able to create “a range of different cultural gestures in a way that was unique and powerful and evocative.”

Ailey began with a solely African American ensemble, as he set out to represent black culture in American life. “The cultural heritage of the American Negro is one of America’s richest treasures,” he wrote in one set of program notes. “From his roots as a slave, the American Negro—sometimes sorrowing, sometimes jubilant but always hopeful—has touched, illuminated, and influenced the most remote preserves of world civilization. I and my dance theater celebrate this trembling beauty.”

He highlighted the “rich heritage of African Americans within this culture,” placing that history at “the root” of America, says Combs. “He really was utilizing the dance form as a way to celebrate all of the riches and all of the traditions,” She argues that he was able to show that “through some of the pain, through some of the sorrow, we still are able to extract tremendous joy.”

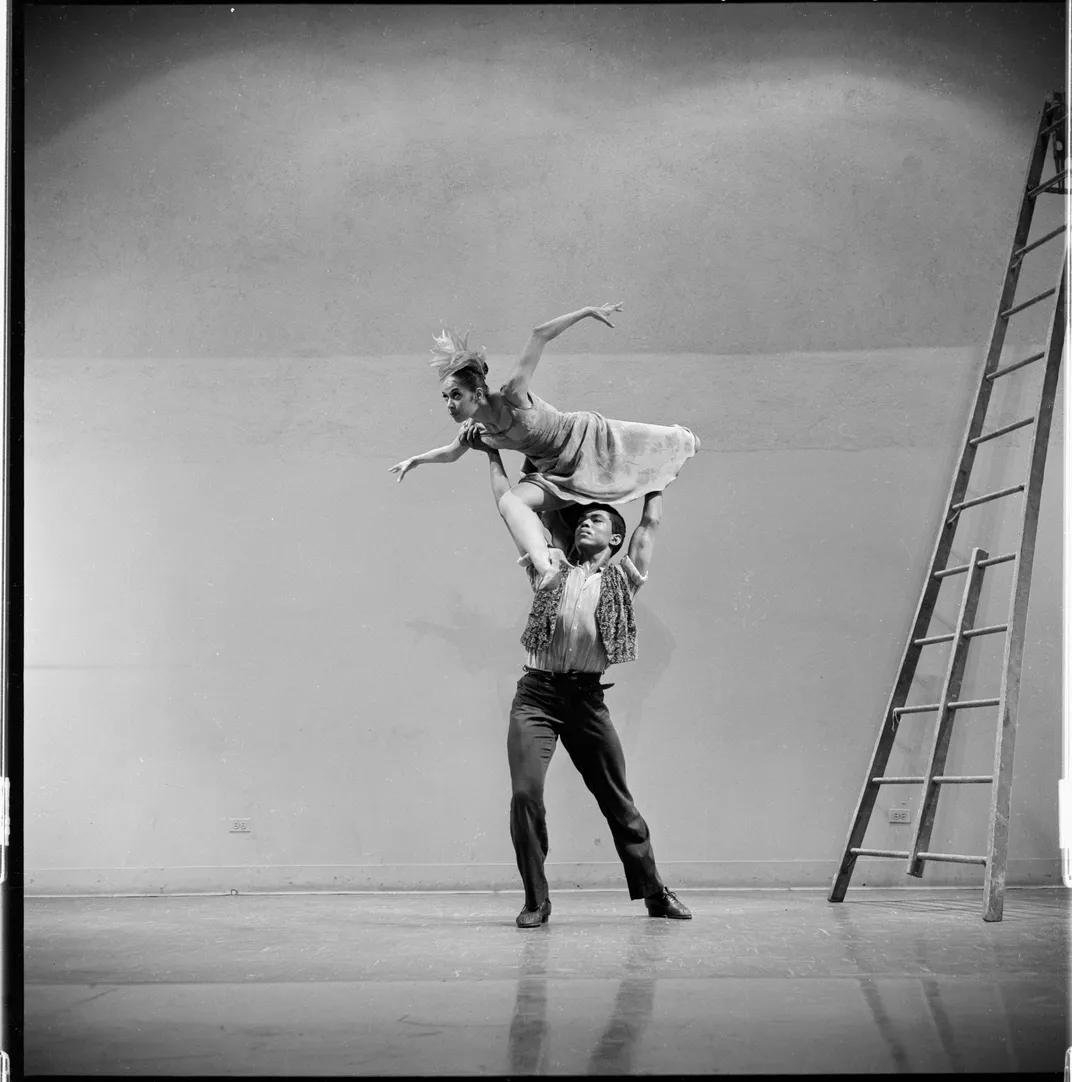

Though Ailey never abandoned the goal of celebrating African American culture, he welcomed performers of other ethnicities over time. In his autobiography, Revelations, he noted, “I got flak from some black groups who resented it.” He later said, “I am trying to show the world we are all human beings, that color is not important, that what is important is the quality of our work, of a culture in which the young are not afraid to take chances and can hold onto their values and self-esteem, especially in the arts and in dance.” Combs believes Ailey was trying to reflect America’s good intentions by providing “examples of harmonious interracial experiences.”

Ailey’s most revered work was “Revelations,” which debuted in 1960. It traced the African American journey from slavery to the last half of the 2oth century and relied on the kind of church spirituals he had heard as a child. In his career, he created about 80 ballets, including works for the American Ballet Theatre, the Joffrey Ballet and the LaScala Opera Ballet.

Shortly before he died of AIDS complications in 1989, Ailey said, “No other company around [today] does what we do, requires the same range, challenges both the dancers and the audience to the same degree.” After his death, ballet star Mikhail Baryshnikov said, “He was a friend, and he had a big heart and a tremendous love of the dance. . . .His work made an important contribution to American culture.” Composer and performer Wynton Marsalis saluted Ailey, saying “he knew that African-American culture was fundamentally located in the heart of American culture and that to love one did not mean that you didn’t love the other.” Dancer Judith Jamison, who was Ailey’s star and muse for years and ultimately replaced him as choreographer, recalled, “He gave me legs until I could stand on my own as a dancer and a choreographer. He made us believe we could fly.”

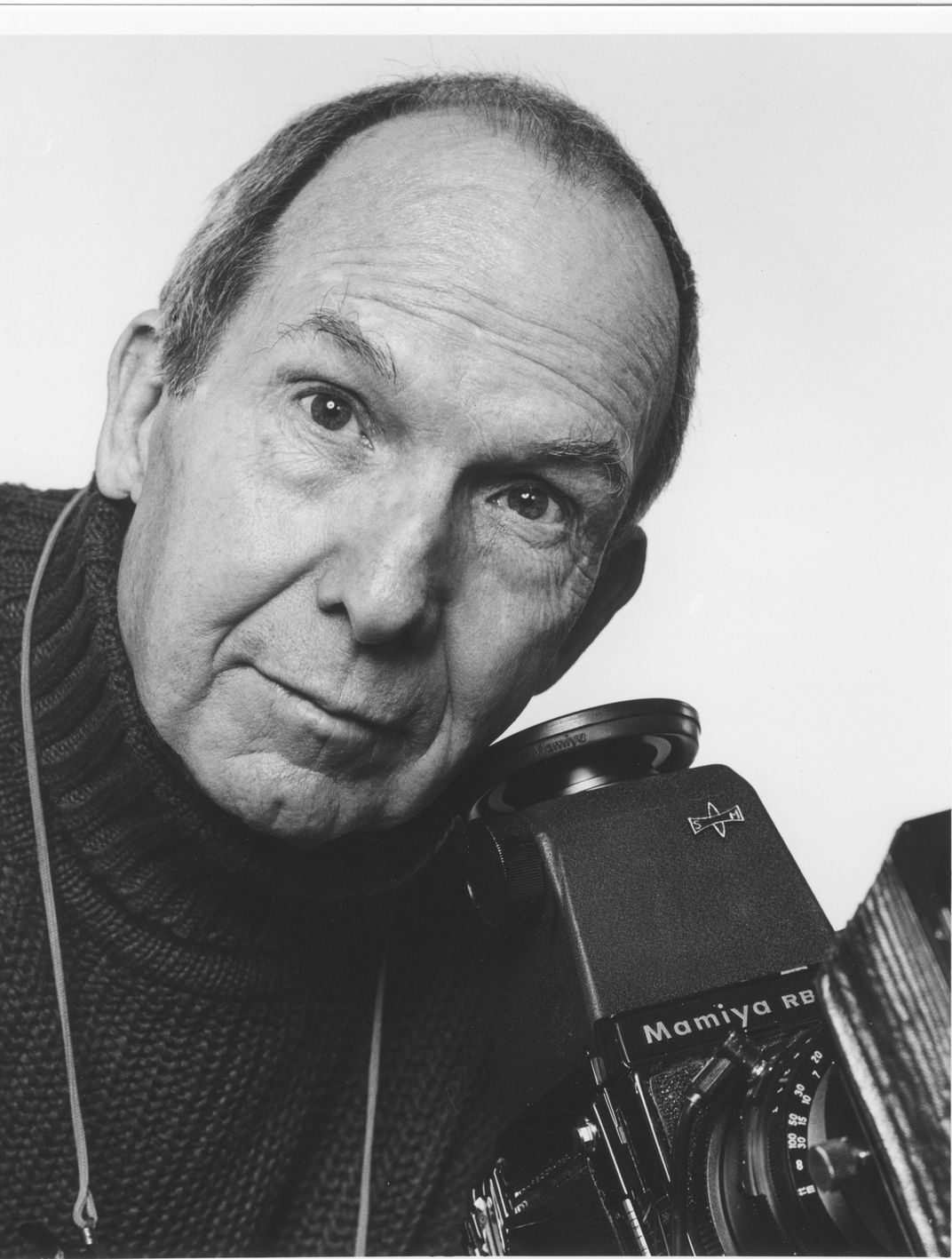

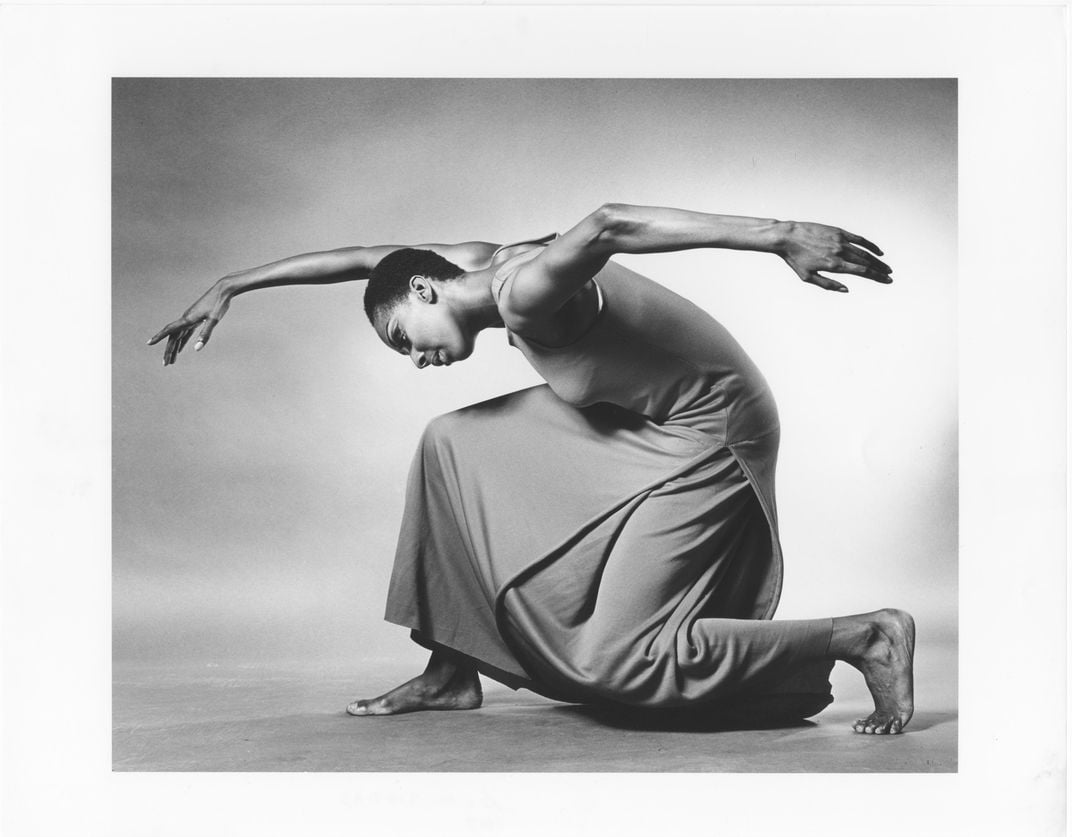

When Ailey died, Mitchell’s long career was nearing its end. His career had begun in a flash after his father gave him a camera during his adolescence. He became a professional photographer at 16, and by the time he was 24, he had begun capturing images of dancers. As he developed expertise in dance photography, he created a name for what he was seeking to capture—“moving stills.” This form of artistry “embodies the difficult nature of what he was capturing” in photos, Combs argues. Acknowledging that ballet sometimes seems to defy “the laws of physics,” she praises Mitchell’s ability “to capture that within a single frame, to allow our eyes an opportunity to gaze on again, the grace of this movement, of this motion. . . hold it in the air, in space, in time.”

By 1961 when he began working with Ailey, Mitchell said he had started “to think of photography more as a preconceived interpretation and statement than as a record.” The working partnership between Mitchell and the company lasted more than three decades.

Known for his skill in lighting, Mitchell developed a reputation for photographing celebrities, primarily in black and white. Some fans described him as someone who could provide insight into the character of his subject. He devoted 10 years to a continuing study of actress Gloria Swanson and captured a well-known image of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Writing the foreword for Mitchell’s 1998 book, Icons and Idols, playwright Edward Albee asked, “How can Jack Mitchell see with my eye, how can he let me see, touch, even smell my experiences? Well, simply enough, he is an amazing artist.”

Mitchell retired in 1995 at 70. Over the course of his career, he accepted 5,240 assignments in black-and-white photography alone. He made no effort to count color assignments, but he created 163 cover images for Dance Magazine and filled four books with highlights of his work. He died at 88 in 2013.

In 1962, Alvin Ailey’s company began traveling the world to represent the American arts on State Department-financed tours sponsored by President John F. Kennedy’s President’s Special International Exchange Program for Cultural Presentations. By 2019, the company had performed for approximately 25 million people in 71 nations on six continents. The group’s travels included a 10-country African tour in 1967, a visit to the Soviet Union three years later, and a ground-breaking Chinese tour in 1985. Ailey’s corps of dancers has performed at the White House multiple times and at the opening ceremonies of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. In 2008, longtime Ailey friend and dancer Carmen de Lavallade declared that “today the name Alvin Ailey might as well be Coca-Cola; it’s known all over the world.” He became, in Combs’s words, “an international figure able to take very personal experiences of his background, his life, and his culture . . . and connect with folks all over the world.”

The work Mitchell produced in his association with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater lives on in digital images available to the world through the museum’s website. “Their collaborative work was a tantamount example of this magic that can happen through art,” says Combs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/e6/b3e60158-bf8c-4357-9261-61b86de6efe3/beth_img_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/25/7c25ea75-f792-4ebe-a1d8-1085ce7a0387/a2013_245_1_2_4_15_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)