The True History of Luke Skywalker’s Monastic Retreat

A Smithsonian Librarian delves into centuries of maps and manuscripts to discover ancient stories of this sacred place and sanctuary

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/11/3211040f-4559-494e-a97b-9f396b7c00fe/scanimage004-wr.jpg)

The Skellig Islands are more stunning and other-worldly than any of the special effects of the past two Star Wars movies. Long before Luke Skywalker arrived on the scene, the real-life towering rock outcroppings glimpsed in the closing moments of the 2015 film The Force Awakens and now playing a starring role in the blockbuster, The Last Jedi, have been a sacred place of retreat, pilgrimage and sanctuary.

Although the Great Skellig, also known as Skellig Michael and Sceilig Mhichíl, and the Lesser (or Little) Skellig appear to be in a galaxy far, far away, they are in fact about eight miles off the dramatic southwest Atlantic coast of Ireland.

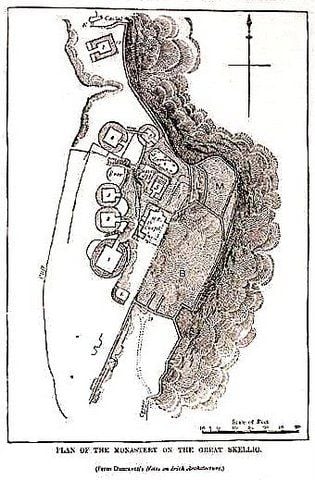

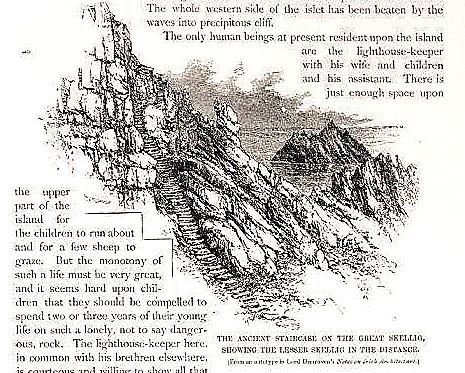

Trekking up 618 steps cut into the sea-bitten cliffs, a visitor arrives at Great Skellig’s ancient monastery near its 715-foot summit. Several structures have miraculously survived Viking raids, relentless gales and the test of time. Inspired by the Coptic Church of Egypt and Libya, and St. Anthony in the Desert, Gaelic Christian monks sought extreme solitude here beginning sometime in the 6th to 8th centuries and lasting through the late 12th or early 13th century.

There one can find the remains of an abbey, with a later medieval church built upon it, two oratory chapels, a cemetery with stone crosses, and, on the southern of the two peaks, the remnants of a hermitage with three separate terraces. Six complete drystone beehive cells, or dwelling houses, were home to an estimated 12 monks and an abbot. The church, unlike the beehive dwellings, was erected with mortar and dedicated at least in the 11th century to Saint Michael.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries in 1578, the islands passed to the private ownership of the Butler family. The Irish Government took possession in the 1820s to erect two lighthouses. One became automated in the 1980s, maintaining a still much-needed beacon on the Atlantic side, where the seas are unpredictable and often turbulent. Since 1880, the Irish Office of Public Works took over maintenance of the archaeological site.

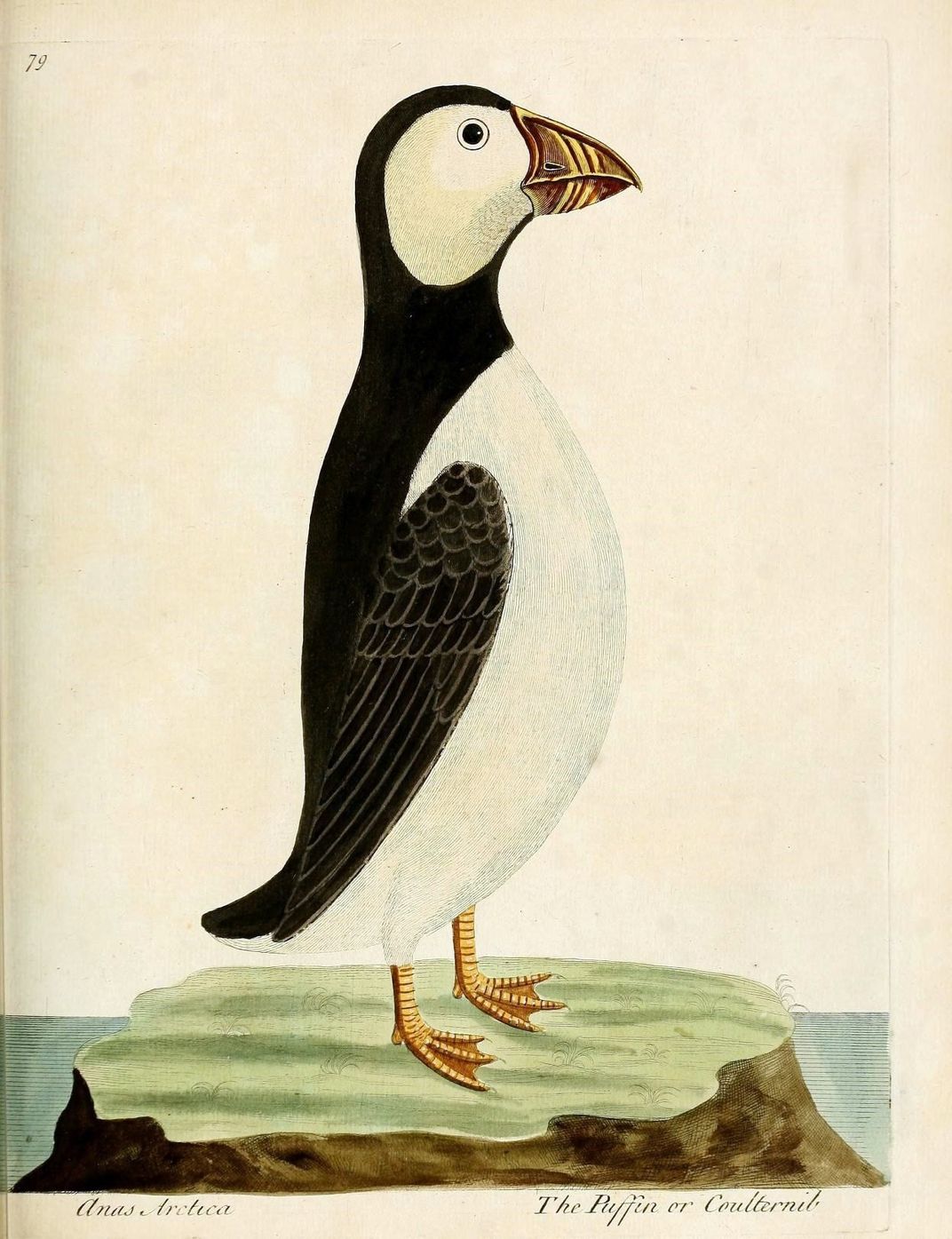

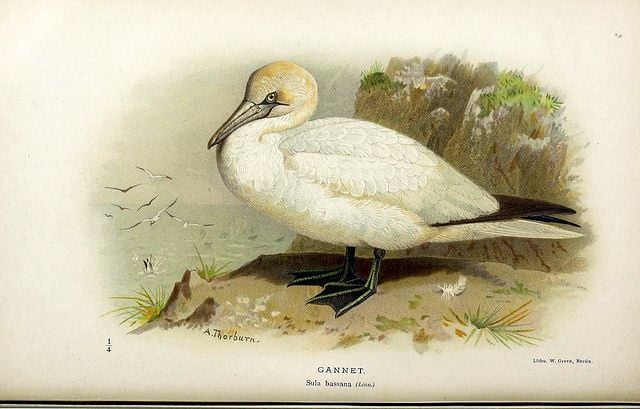

Little Skellig, where boats are not allowed to land, is a seabird sanctuary to one of the largest colonies in the world of northern gannets. The islands are also protected habitats for Manx shearwaters, northern fulmar, black-legged kittiwake, razorbill, guillemot, peregrine falcon and storm petrel. But the area is best known for the colorful-beaked puffins.

Thousands of the birds make their home on the island to nest and rear their young during a short summer season. Sturdy and looking like they sport a cap and cloak, the seabirds have short wings that are designed for swimming underwater, yet can also carry the puffin long distances in flight.

The puffins of Skellig Michael are said to be the inspiration for those too-cute-by-far porgs, the indigenous inhabitants of Luke Skywalker’s island, named Ahch-To in the films. But the porgs have nothing on the almost comical puffin.

The record of the Skellig Islands is long and can be traced in libraries and archives. The death of a monk is noted in the Martyrology of Tallaght, a manuscript dating from the end of the 8th century. The rock formations appear in charts from the 14th century and are referenced in contemporary accounts of the 1588 Spanish Armada. The first modern description of Skellig Michael is in Charles Smith’s Antient and Present State of the County of Kerry of 1756.

Some accounts in the 18th and 19th centuries erroneously note that the Skelligs were made up of three separate islands, as the craggy peaks appear when viewed at a distance from the mainland, and to be made of marble. The legend is that the monastery was founded by St. Finnian of Clonard, one of the fathers of Irish monasticism, although there is no evidence of this. Nicholas Carlisle’s A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London, 1810) repeats these claims. What the various books all emphasize is the Skelligs’ remoteness and spiritual nature.

There is a lyrical, almost mystical, description in Ireland Illustrated with Pen and Pencil (1891) by Richard Lovett.

It is good for the soul to be thus lifted out of and away from all the mean and petty detail of life, to escape from the wearing friction of the selfish every-day life, and to be alone with the noblest natural features—the wide sky, the broad and health-giving ocean, the immovable rock, so firmly rooted that through countless generations the Atlantic surges have vainly thundered against it.

Lovett also informs of the features of the site, some (notably crosses and carved slabs) which have collapsed with time:

Half way up the ascent is a little valley between the two peaks, in shape something like a saddle, and known as ‘Christ’s Saddle,’ or the Garden of the Passion. From this place what is known as the Way of the Cross rises up, and at one part a rock has been shaped into the form of a rude cross.

This author also details enclosing walls, two wells, five places of entombment, and the Monks’ Garden. There were several cisterns for collecting rain water. The retaining walls created a micro-climate for growing vegetables and herbs. During a recent excavation, the garden was discovered to have peaty soil.

While inhabited for an incredibly lengthy period, the monastery was abandoned probably by the early 13th century, while remaining as a place of periodic penitence and continued pilgrimage. Nathaniel Parker Willis in The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland relates the monks’ relocation to the more hospitable nearby coast:

The Skellig Islands, which lie outside the bay of Ballinskellig, have some of the romance of antiquity hanging round them … An abbey was founded … but the bleakness of the situation and the difficulty of access, induced the residences to remove in after times to the mainland, where the monastery of Ballinskellig still marks the circumstances of their change of place. (volume 2, page 102).

This relocation was also due to the monastic life in Ireland moving away from the ascetic Celtic model with its emphasis on solitude to the more engaged Augustinian Church.

The enigmatic island of hermetic monks, devoted to a life of prayer and study, has long been venerated, serving as a place of sacred pilgrimage since the medieval period, and a site to study bird life without much human interference. But can Skellig Michael survive a new type of pilgrim, the legions of Star Wars fans?

The island was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. The importance of protecting the seabird nesting habitat has long been recognized. Fragile both architecturally and topographically, visitor access has been limited and only licensed boat operators can bring passengers to disembark on the island.

Despite the restrictions, the distance from the mainland, and the difficulty of the often-rough seas and arduous climb only for the able-bodied (three tourists have fallen to their deaths since 1995), the number of access permits has been recently increased to accommodate demand. There are fears the remote location is becoming a “Disneyesque theme site.” Skellig Michael is now facing the not-uncommon issues of preservation versus the impact of popularity.

There are centuries of maps, manuscripts, works of art, and books preserved in repositories such as the Smithsonian and digitized in the Biodiversity Heritage Library to stand testament to the mystical Skelligs and their astounding natural life. Surely there must be some written legend of a sea monster like the one that appears cavorting in the background in one scene in The Last Jedi?

And about those sacred Jedi texts—wonderfully bound books and scrolls shelved in that tree library on the island. Like Luke, they are “the last of the Jedi religion.” Spoiler alert: the collection was apparently moved by Rey to the Millennium Falcon. Maybe a librarian will enter the scene in the next movie installment, ensuring the volumes are properly cataloged, conserved and disseminated for the preservation of the Force.

A version of this article appeared on the Smithsonian Libraries blog “Unbound.”