To Truly Experience Robert Irwin, You Simply Must View His Artworks in Person

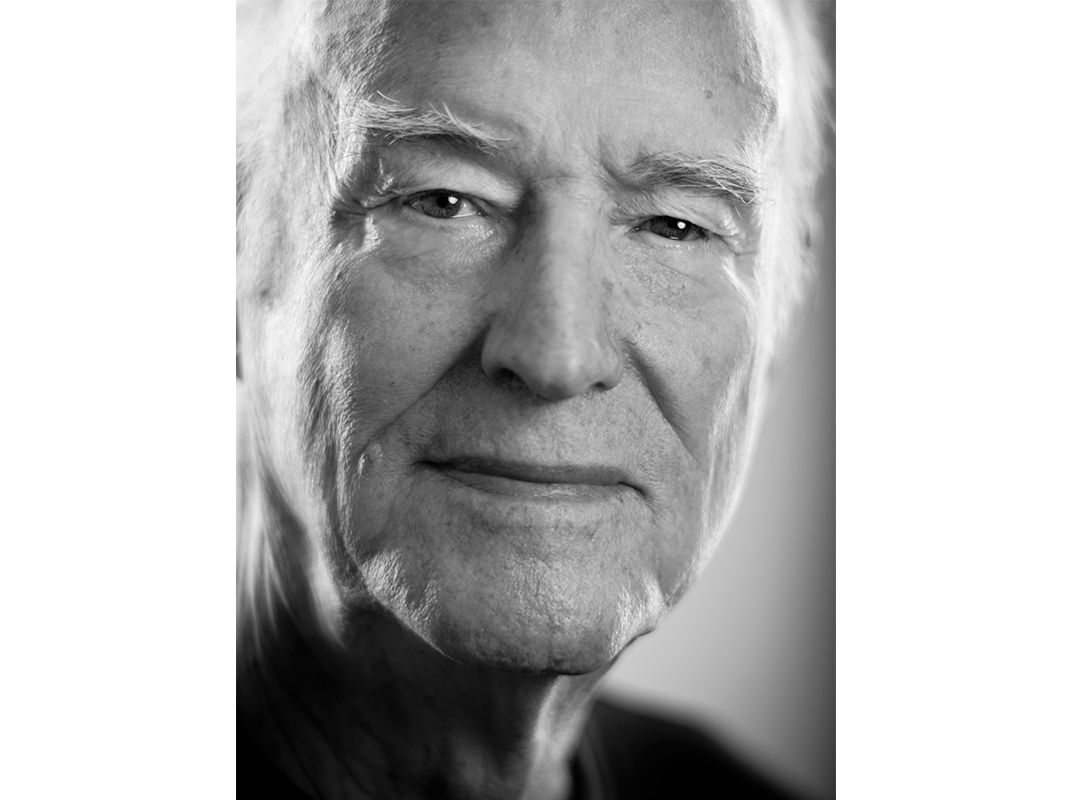

Part visionary, part magician, Irwin makes art that breaks all the rules

The new Robert Irwin survey at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., is a kind of a disappearing act.

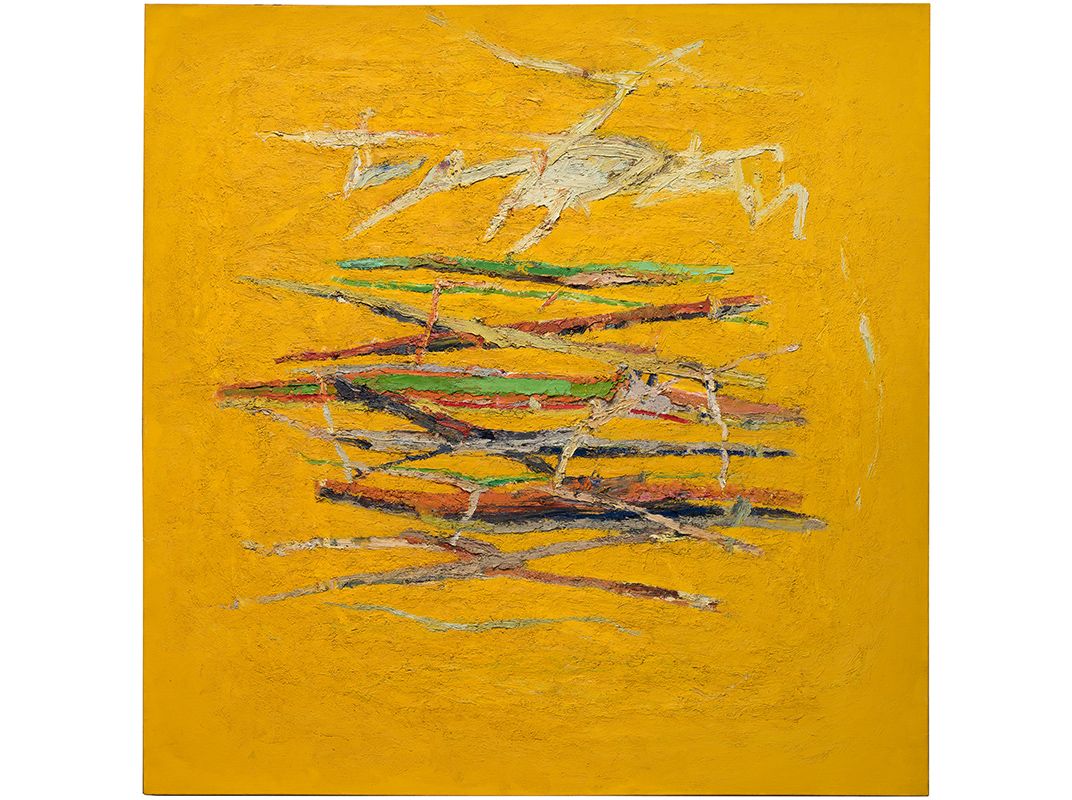

Throughout his influential career, the California artist has tried to find ways to undermine every convention of the art world. First, he eliminated the need for walls around his abstract paintings by making them purposely “hand-held,” to be admired and examined as they were handled by viewers. Then he eliminated the slashes of the abstract expressionism that was drawing him some early attention, reducing the content to cool, austere lines on canvases.

Then, came the elimination of canvases themselves. Just before he ditched his studio entirely in 1970, he began to concentrate on cool discs of aluminum or plastic, whose interplay with shadows seemed to blur edges such that one was never sure where the object began or ended. And finally, for a time, he refused to allow his works to even be photographed.

It figures, then, that “Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change,” the first U.S. museum survey of the artist outside of California in nearly four decades, which is on view through September 5, 2016, begins with one of his sleek, untitled discs, commanding its own space, hovering in place amid unblinking spotlights.

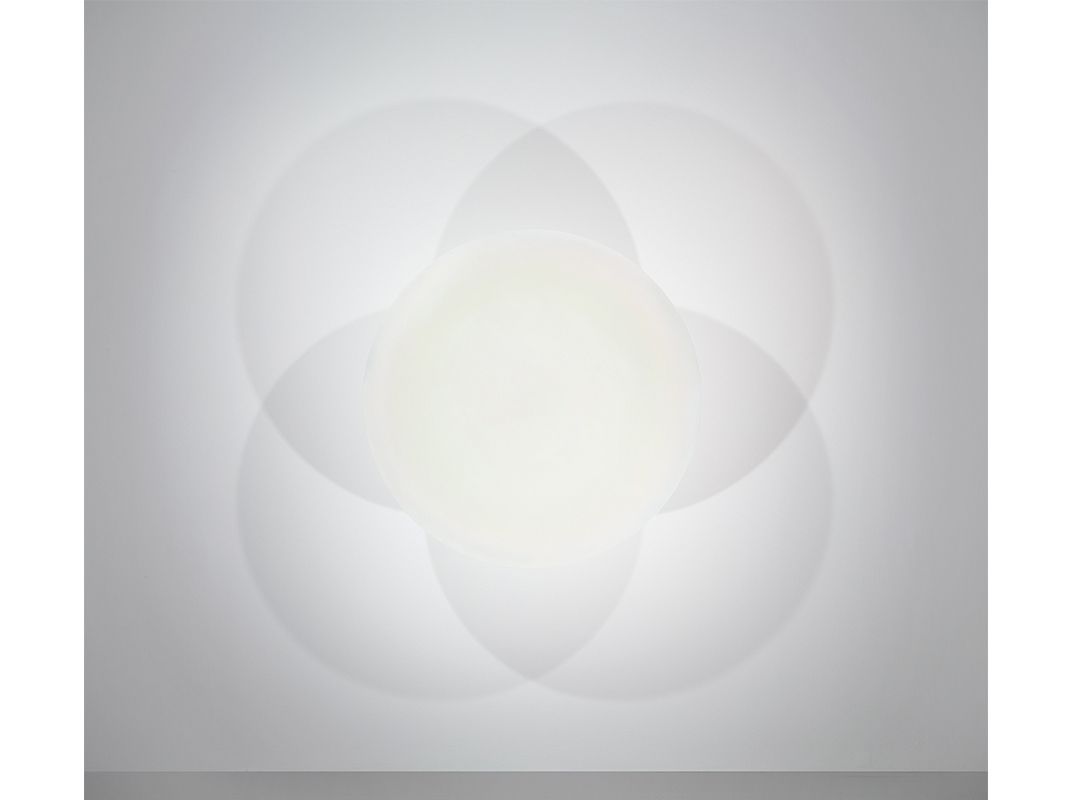

The circular galleries of the Gordon Bunshaft-designed Hirshhorn seem perfectly suited for Irwin’s work; one begins not far from where one ends. But Irwin, still very active at 87, also plays with the space for his latest large-scale installation—one so subtle one might not think it’s there at all. Opposite one long expanse of the curved, freshly painted walls (in a tempered gray, not white) he’s installed one of his eye-fooling floor-to-ceiling stretches of straight white scrim, more than 100 feet of it.

The most immediately discerned aspect of the installation is a rectangle of light surrounding the outlined doorway to the interior hall. Special lighting? No, it’s courtesy of light shining in from the courtyard windows beyond.

More significant in the piece titled Square the Circle is that the building’s very structure, curving around, is straightened such that its hidden rounded corner becomes barely discernible through the scrim. It’s seen as if through a cloud, dissolving, much like the edges of the discs nearby, into ether.

After having eliminated paint, canvas and even object in his career, Irwin succeeds in eliminating aspects of the museum as well.

The full act of elimination, though, came when his initial plans for a Hirshhorn installation first submitted three years ago, involving a series of outdoor scrims in the museum’s plaza in the underpinnings of Bunshaft’s famed building, were scrapped.

Because it would be exposed to D.C.’s unpredictable weather, it did not pass the muster of a year-long feasibility study that involved architects and structural engineers from the Smithsonian’s Office of Facilities Engineering and Operations and the staff of the University of Maryland’s Glenn L. Martin Wind Tunnel, as well as aerodynamics experts from the nearby National Air and Space Museum.

“Ultimately,” says show curator Evelyn Hankins, “a design satisfying all requirements could not be achieved, and plans for Irwin’s outdoor installation were abandoned.”

The subsequent indoor Square the Circle leaps ahead more than four decades past the concentration of the survey which otherwise covers 1958 to 1970. But it isn’t the only thing that provides a modern representation of the longtime artist.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/57/fb57d4e8-9e40-4e8f-894a-1b5a6bb8408c/irwin-studio-1970-web-resize.jpg)

His two nearly 16-feet tall clear acrylic columns, which take advantage of another window that shines into the exhibition space, have an unusual completion date that spans decades—1969 to 2011.

That means the work was conceived in the last century, but it wasn’t until more recently that the technology existed to successfully manufacture acrylic columns that tall. A Hirshhorn-owned Irwin column (not in the show) is 12-feet tall, but was made from two six-foot lengths laminated together. Seams detracted from a work that was meant to not call attention to itself but to fan and refract light into its dedicated gallery, which the tall ones do now.

Considering Irwin’s strict involvement in every aspect of the exhibit design, though, one might consider the austere layout of "All the Rules Will Change" as a second example of one of his modern installations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/59/d7592cb0-4cae-4396-8a5d-1ad5eca29909/robert-irwin_131-2-3_hirshhorn-web-resize.jpg)

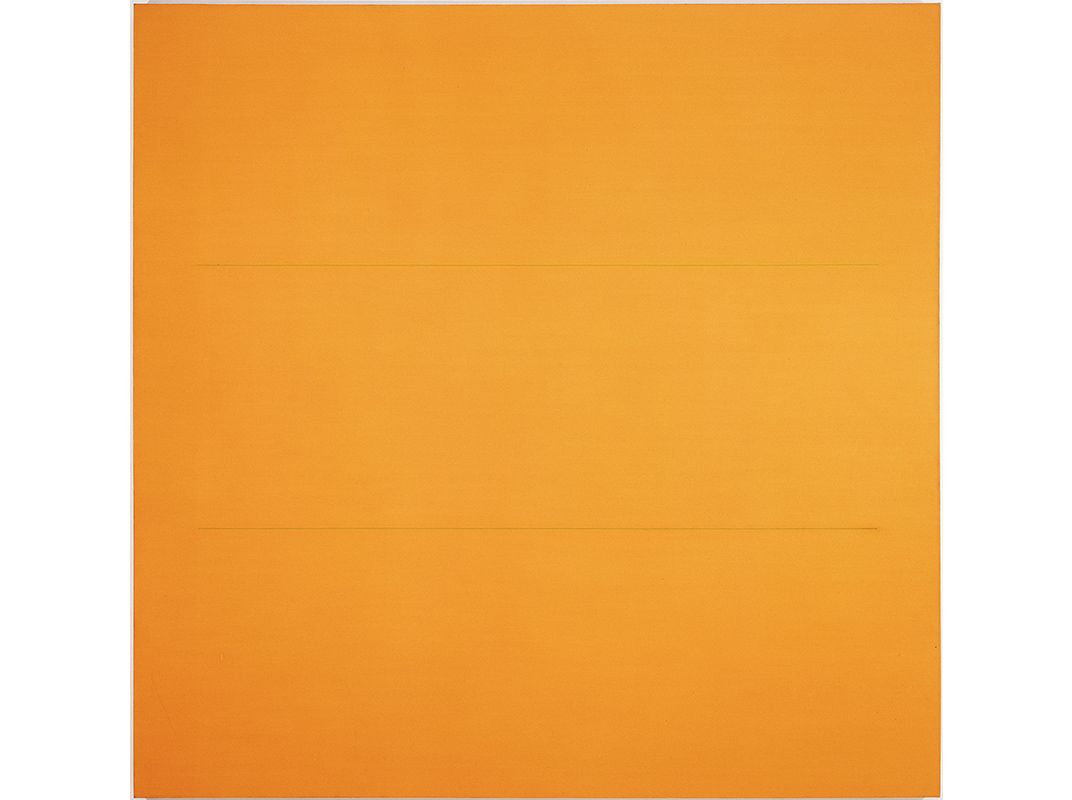

In a number of the galleries of the generally chronological overview, the larger earlier abstract paintings hang two to the gallery—one opposite another. There one can see the works with a series of slashes that gave them the name “pick-up sticks paintings” gradually evolve to the more coolly composed abstracts of a few horizontal lines.

The line paintings become more subtle as time goes on, their initially contrasting colors giving way to harder to perceive contrasts against near identical background fields in an optical exercise worthy of Ad Reinhardt.

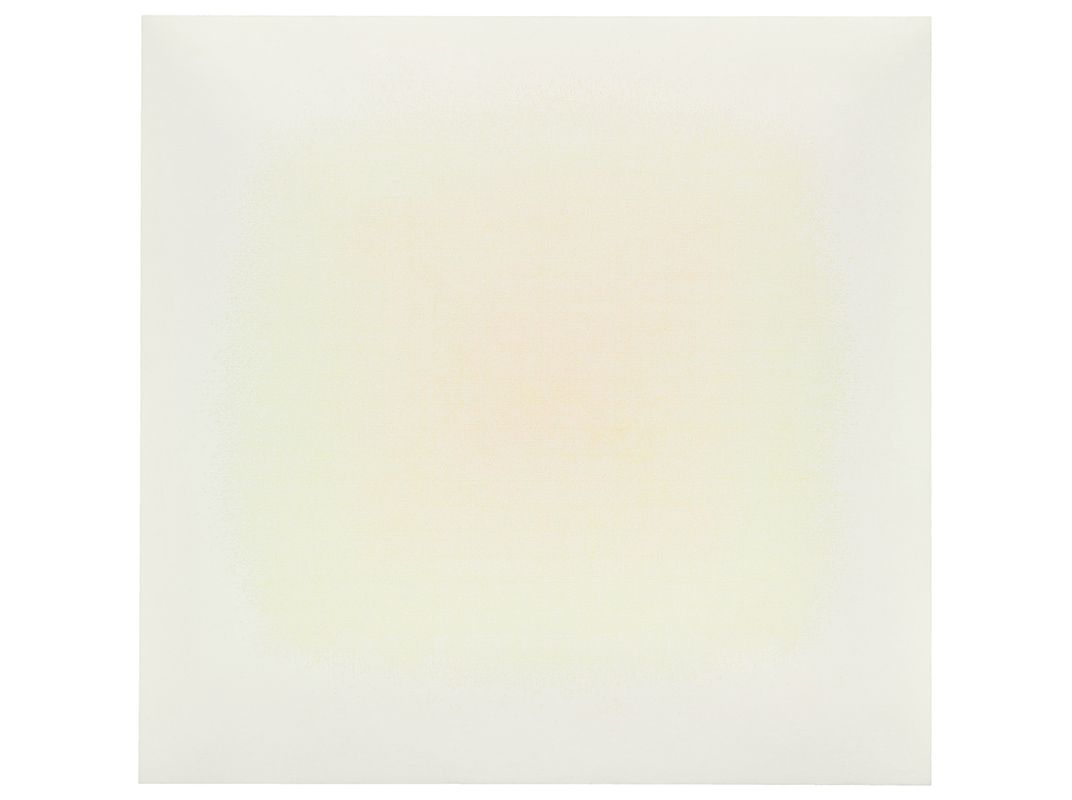

Then, for the Dot paintings, the lines drop away altogether (in fact, the floor demarcation that keeps viewers a safe distance from the Dot paintings at first looks like an Irwin line that has fully slid to the ground).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/6a/066a3de2-491f-43af-961f-642fe3b15a72/irwin_131-2-18_hirshhorn-web-resize.jpg)

At first looking like barely perceptible, cloud-like variations in tone, the paintings are true to their name. We learn from a Susan Lake essay in the exhibition catalog, they are made instead of thousands of small dots, often of differing complementary colors, administered uniformly but of erratic shape and applied by the spikes beneath a cashier’s mat dipped in paint.

Not only does the gauzy cloud of changed color point toward his upcoming disc works, so does their shape. The canvases jut out from the wall and curve convexly to the viewers, as if coming out to meet them halfway.

The eventual discs will soon provide a similar experience, using entirely different space age materials.

From the time he was doing line paintings, Irwin earned some notoriety for refusing to have his work photographed. Photos never convey the experience of seeing art in person, he maintained, until he realized the very act of refusing cameras took attention away from the work as well.

“The ban itself had never been the point, and yet that is what I was becoming known for, which is silly,” Irwin told author Lawrence Weschler in the monograph Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees. (Both Irwin and Weschler will speak at the museum at separate events in conjunction with the exhibit).

Though Irwin abandoned the photo rule, he eventually began making pieces that mere photographs simply could not convey.

They are works that, according to Hankins, “because of their extremely subtle nature, demand in-person viewing.”

“Irwin’s art becomes fully present,” she says, “only when you are standing in the physical space, experiencing it over an extended period of time.”

Says museum director Melissa Chiu, “The Hirshhorn is honored to introduce Irwin’s intellectually rigorous and indescribably beautiful work to a new generation of viewers.”

“Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change” continues through September 5, 2016 at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

UPDATE 4/12/2016: This article contains additional information about the acrylic columns.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)