Truth Is Stranger Than Fiction With Horten’s All-Wing Aircraft Design

New research dispels some of the myths behind the world’s first jet-powered flying wing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/5b/065b342f-8eb0-4202-bd48-9593f472f4c8/https___airandspacesiedu_webimages_collections_full_a19600324000cp08jpg.jpg)

In the 2011 movie Captain America: The First Avenger, the eponymous hero battles the evil Nazi Red Scull onboard a sleek, menacing all-wing aircraft in the waning days of World War II. The future of freedom hangs in the balance as the sophisticated jet plane zooms toward New York City with a payload of super weapons intended for total annihilation.

Of course, it’s all Hollywood CGI and comic-book action rolled into a blockbuster film—the stuff of dreams and star-studded spectaculars. All made up, that is, except for one thing: the huge bomber. While it is certainly the product of a director’s hyperactive imagination, it is strikingly similar to the Ho 229 V3, the first jet-powered flying wing, preserved and on display at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

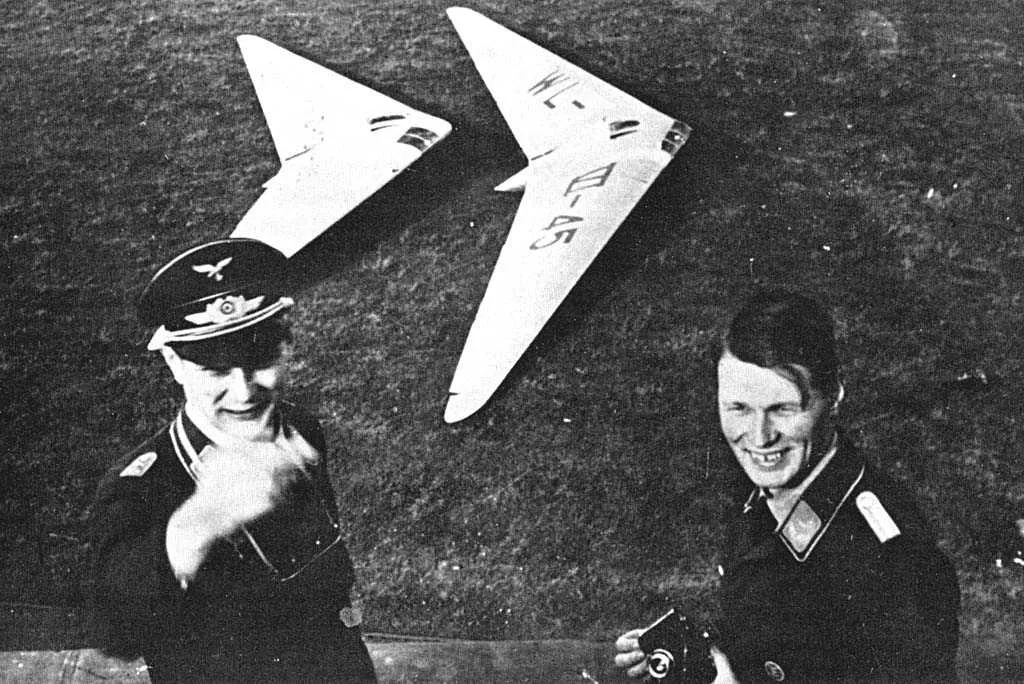

That’s because this conceptualization comes directly from the promising prototypes and plans of Germany’s Horten brothers, Reimer and Walter, who conceived and developed the idea of an all-wing aircraft before and during World War II. Their work on dozens of creations of large winged gliders and jet-powered planes, including a four-engine bomber akin to the one in the film, primed the creative juices of future engineers who would eventually develop the Northrop Grumman B-2 stealth bomber and similar aircraft.

“Reimar was a brilliant designer and Walter was a fighter pilot,” says Russell E. Lee, curator in the aeronautics department of the National Air and Space Museum. “One of the lessons they took from the Battle of Britain was the need for a new fighter aircraft. Walter thought the all-wing plane was the answer to Germany’s needs. In about 1942, both brothers put pen to paper and designed something that eventually became the Horten 229.”

Only the Wing: Reimar Horten's Epic Quest to Stabilize and Control the All-Wing Aircraft / With a New Introduction

In the late 1920s, Reimar Horten began experimenting with flying models equipped with fuselages, stabilizers, rudders and elevators, but his life’s work involved systematically removing these components from models until he could achieve flight with only the wing. Russell E. Lee is a curator in the aeronautics division at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Lee wrote the book—literally—on that aircraft, its development and Reimer Horten's career. Originally published in 2011, a second edition of Only the Wing: Reimar Horten’s Epic Quest to Stabilize and Control the All-Wing Aircraft was released last month. It includes a new introduction that discusses recent developments and dispels some of the myths that have taken root over time.

One such legend was the Ho 229’s stealth capability. It was fueled by the aircraft’s unique design—a cross between a “Star Wars” Snowspeeder and U-2 Spy Plane with its wings bent back at a sharp angle. Comments made by Reimar Horten after the war led enthusiasts to speculate that the plane could elude radar and fly undetected by enemy observers.

“Reimar argued that he understood the chemistry of stealth coatings and was going to, or had, added this material into the Ho 229 V3,” Lee says. “So this whole mythology developed about it being the first stealth fighter. A good portion of the new introduction to my book is looking at what our wonderful team of conservators, led by Lauren Horelick, did to very scientifically determine whether or not there was a stealth coating.”

The aircraft’s aerodynamic shape made it somewhat less visible to radar because its smooth surfaces and lack of sharp angles could deflect some of those waves, Lee notes. The Smithsonian team wanted to be sure, so it examined the plane and even took samples of coatings to make a determination. Its conclusion?

“While somewhat ambiguous, they fall on the side that there was not an intentional plan to make it stealthy,” Lee says.

Regardless of Horten’s hopes, this airplane was definitely ahead of its time. With a 50-foot wingspan pitched at a 32-degree angle and no tail, it looked unlike any other aircraft of its day. On paper, it could outmaneuver the German Me 262, the first operational jet fighter, while achieving speeds in excess of 600 miles per hour. By comparison, it could easily outpace the American P-51 Mustang at 437 mph and British Supermarine Spitfire at 330 mph—both powered by piston-driven engines.

All-wing aircraft had been a goal of designers since the dawn of crewed flight. Reimar and Walter Horten were among the first to develop a workable model that showed the promise of being able to do what had been envisioned for decades.

The brothers grew up between the two world wars at a time when Germany was restricted in developing motorized aircraft by the Treaty of Versailles. Reimar experimented with all-wing gliders and created several prototypes with low drag coefficients and impressive lift distribution.

Because of his lack of aeronautical training, Reimar was snubbed by other designers and worked independently on his innovative concepts for flight. When World War II erupted, the brothers began thinking about a jet-powered all-wing fighter. One idea so impressed Luftwaffe Supreme Commander Hermann Göring that he allotted 500,000 Reichsmarks for the development of three prototypes.

Reimar named it the H.IX, later dubbed Ho 229 by the German air force. The three prototypes became V1, V2 and V3. All versions closely resembled each other with minor modifications for improved performance. Each included elevons, spoilers, drag rudders, flaps and speed brakes along with extremely long wings and no tail.

Featuring steel-tube frames with laminated and layered wood surfaces, the planes were equipped with tricycle landing gear.

“In terms of just getting it to fly, it’s a groundbreaker,” Lee says. “There was nothing else like it in all the air forces in the world at the time. However, a huge, huge amount of work had to be done to make it go to the next step and become a practical airplane that could do the job.”

The V1, a glider model, took to the air on February 28, 1944 and went through several successful test flights, though there were some small accidents with the revolutionary design. Reimar quickly began building a powered version with two Junkers 004 turbojet engines.

The V2 flew three times, beginning with its first flight on February 2, 1945. On the second flight a few days later, it was damaged during a crash landing and required extensive repairs. While the V2 performed well, there were still serious problems that needed to be worked out.

“It was an experimental aircraft,” Lee says. “You can experiment very, very carefully with an airplane that is far from practical as long as it’s reasonably safe for the test pilot, but this wasn’t even close to that point.”

The third flight on February 18 proved disastrous. The V2 took off without issue but soon there was a problem. Test pilot Lieutenant Erwin Ziller was killed when the aircraft spiraled into the ground. It was later determined that one of the engines had failed and there was also speculation that Ziller had been overcome by fumes. Walter believed the plane had been sabotaged.

“It was an awful event,” he later said. “All our work was over at this moment.”

Development did continue with the Ho 229 V3. This version never flew. Later versions were to be equipped with two 30 mm cannons. The war in Europe ended nearly three months later and this half-completed prototype, along with three other unfinished models, were captured by General George S. Patton’s Third Army. The Allies never found a working version of the H.XVIII, the huge intercontinental bomber that inspired the Captain America movie.

“It only got to sketches and brief reports,” Lee says. “There was never any wood or metal construction. It was just hypothetical. That’s another thing that grew up to be mythology—that they were going to build this Amerika bomber—but it wasn’t very far along at all.”

Military officials brought the all-wing jetfighter to America for study with hopes of discovering its secrets. The U.S. Air Force donated the V3 and several early Horten gliders to what became the National Air and Space Museum in 1952, though preservation work did not begin until 2011.

After World War II, the brothers went their separate ways. Walter remained in Germany and became an officer in the country’s newly reconstituted air force. Reimar emigrated to Argentina, where he continued his research into all-wing aircraft but never equaled the success he had with the Ho 229. The aircraft designer died in 1994 and his brother in 1998.

“Reimar had fallen on hard times in the 1950s,” Lee says. “At that time, Argentina did not have the aeronautical resources of the United States. I don’t think he realized that until after he got there. If things had gone differently, who knows what he could have accomplished?”

Today, the experimental aircraft is on display in the museum’s Boeing Aviation Hangar in an exhibit that features the center section of the plane standing on its landing gear with cockpit and jet engines clearly visible. The wings with Balkenkreuz—the German cross insignia—are stored nearby.

Conservators had their work cut out for them. The Ho 229 V3 showed considerable deterioration after being stored outdoors for many years. The laminated wood was separating, paint flaking and metal rusty. Still, peering at its sleek design and advanced aerodynamics, it was easy to see why this aircraft captured the imagination of aviation designers and enthusiasts around the world.

“It’s the only one of its kind,” Lee says. “We’ve taken the time and effort to preserve it and save it and now display it for our public. It’s just one of nearly 400 aircraft in our collection that are all significant and all have incredible stories to tell. It’s part of one of the world’s greatest aeronautical collections, if not the greatest.”

Editor's Note: 10/21/2020: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the pilot flew the aircraft in a prone position. We regret the error.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)