A Tweet Is Just a Ritz Cracker, But an IMAX Film Is a Steak Dinner

That’s what astronaut Terry Virts says about the new IMAX film he helped to make

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/9c/e39cb192-a08b-43fc-a958-8d5502ca3a6a/bahama_reefs_imax10480_cc.jpg)

When producers for the TIME and PBS documentary “A Year in Space” interviewed astronaut Terry Virts from space, the self-declared camera guy, who at age 10 was already the owner of his first Konica 35mm SLR, knew they were using Canon C100 or C300 cameras.

“When I told them I was using the C500, the camera guys got really jealous,” he says.

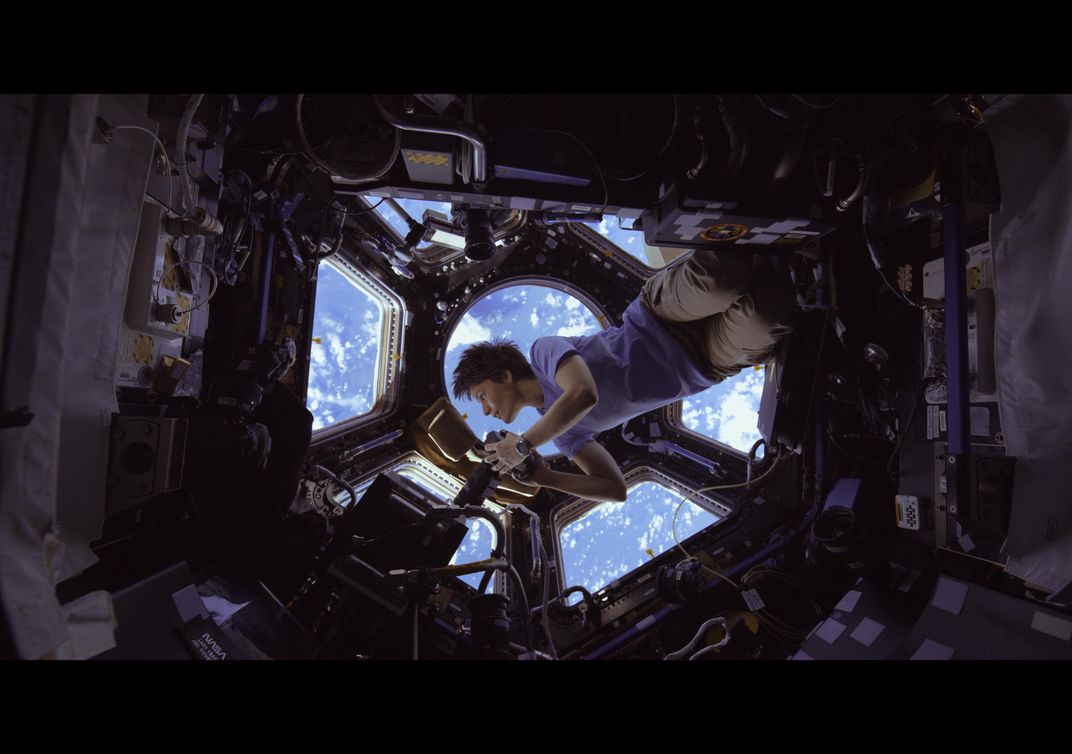

Virts was doing his own camerawork during his six-month stint on the International Space Station, where six astronauts orbit Earth every 90 minutes. The roughly 500,000 still photos and extensive video footage that he shot—the most, he says, of any astronaut—form the basis of the new IMAX film “A Beautiful Planet,” now showing at the IMAX Theaters at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

And the cameras that IMAX flew out to the station impressed not only the documentary producers, but also Hollywood royalty. “I was talking to James Cameron, and he saw my Red [camera],” Virts says. “He said, ‘I filmed Avatar with that camera.’”

Virts cares deeply about educating the public about what it’s like to be an astronaut. And as @AstroTerry on Twitter, he has 225,000 followers. “A Tweet is like a Ritz cracker or a cookie,” he says. “An IMAX movie is a four-course steak dinner. It’s a different way to experience for people who will never get to go to the space station, which is 7 billion of us on earth.”

“This IMAX film was the biggest accomplishment of my space career, because it’s the way that millions of people across the world will see it and get to experience space,” he says.

Another benefit of the equipment that IMAX flew out to the space, in addition to its Hollywood quality, was that it allowed Virts to film at night, where previous cameras required daylight. He was able to showcase some of the most visually arresting sequences of the film: lightning storms, the northern aurora lights, and major world cities illuminated at night. Political borders, however omnipresent on Earth, don’t appear from space, with the exception of the heavily guarded India-Pakistan border, and the utter blackness of North Korea compared to the much brighter South Korea—one of several sobering reflections of the film.

Among the lighter moments are astronauts hanging a stuffed Olaf character, of Frozen fame, from the ceiling of the space station, and anticipating Santa Claus’ arrival through an airlock, because it’s most like a chimney. The movie also captures the tweaks that astronauts make in space to shower, drink espresso, cut their hair, and go about their daily lives in as similar a manner as is possible to living on Earth.

That juxtaposition of both light moments and discussions about political borders and environmental concerns, was intentional, says director Toni Myers, for whom space has been a frequent subject. And a lot of it was driven by the astronauts’ decisions of what to film and to talk about. “I did not stipulate anything about Santa, although I said on my shopping list of desirable scenes … that I’d like to capture a holiday scene,” she says. “They like to surprise you with their creativity. I didn’t give them any guidance about that.”

Virts says he specifically asked that Myers insert the sequence about how the Chesapeake Bay has proven a conservation success story. “I remember that as a kid, not being able to fish,” the Baltimore native says. But the Chesapeake today, after much conservation, is experiencing a record crop, according to Virts. “This is one example of how we can fix things,” he says. “It provides hope. It’s not just doom and gloom.”

The uplifting message comes through in the film, as Virts has trained the camera on the Chesapeake. It’s one of many shots that are so incredibly realistic that viewers are liable to forget that they are in a theater.

At the edges of your vision, one may find that the the spacecraft parts that jut out in one’s 3D glasses are as real as the theater's stairs and banisters leading to your seat. And viewers prone to claustrophobia may struggle watching the astronauts crawl through tight space station corridors. It’s that realistic.

The film, which boasts IMAX’s new laser projection technology, is so crisp that it may remind viewers who wear glasses of donning their first pair, or the way the world looks when a prescription has been tweaked. Both Myers and projectionists keep referring to the new technology’s capacity to create blacker blacks and whiter whites. But that’s only half the story.

The physical tools themselves are revolutionizing the industry in several ways. Chatting in the Air and Space Museum booth following a screening, Pierre Devaux, a 12-year Smithsonian projection veteran, and Dean Fick, technical manager of theaters, recall having to pick up 200-pound films from the loading dock and lug them up the steep staircase leading to the booth. (“I’ve carried 80-pound boxes up those stairs to mount on a projector. Now all you have is a little hard drive,” Myers says.) Fick jokes that he’s put on weight since the switch to digital projections, where films arrive not via truck, but in a digital, encrypted file. Gesturing toward a control panel, Fick clicks on “select show,” calls up A Beautiful Planet, and in a second, he’s ready to go.

“That’s as hard as it is now,” he says. “Before, it took lots of specialized skills to be a projectionist. You had to know how to handle film, so that it didn’t get scratched. You had to know how to splice it and combine the reels together, and how to thread it through the projector without damaging it.” Now the set-up is as easy for projectionists as it is for you to watch a YouTube clip from your home computer.

The new and lighter tools were particularly important in space, where weight comes at a premium. “The shooting in space was orders of magnitude easier,” Myers says. Previously, there was a ceiling of about three minutes of film, and there were no opportunities for second takes. With the new tools, Virts and fellow astronauts could downlink their photos directly to staff on Earth, and when video files were too large, they sent portable hard drives down in cargo shuttles.

“When they’re up there for six months, it’s much more relaxed,” Myers says. And being able to communicate directly with astronauts made things even easier. “You know how it can take 10 emails to accomplish what you can do in one conversation?” she says. Myers was also able to view the footage and send PowerPoints back to Virts, with arrows pointing out aspects of shots that she wanted to discuss.

Back on earth, viewing the finished film on the new IMAX technology represents the “Rolls Royce, no compromise,” says Fick, who oversees Smithsonian theaters. He predicts hundreds of theaters will be using the new projectors by year’s end.

Think of it like a change in the projector’s “light bulb” to a laser one, says Barry Walker, professor of physics and astronomy at University of Delaware, who studies lasers. “This application probably builds on the new, less-expensive and more robust, powerful laser diodes to generate the light,” he says. “It should make the IMAX more portable and cheaper and give other improved specifications like contrast ratio—bright vs. dark—and saturation.”

The equipment, which runs “in excess of $1 million,” according to Fick, involves a filter on the lenses, which allows just the right wavelength for each eye to come through. Each of two projectors puts a slightly different color-balanced wavelength. “The amount of difference between the whitest white and the blackest black is a large part of what fools your brain into thinking that it’s extremely realistic,” he says.

That, it turns out, is the perfect way to view stunning shots of earth from space. “It’s a great universe, but there’s nothing like earth,” Virts says in the film. When he’s reminded in an interview that he mentions “a beautiful planet” in one of his quotes in the film, Virts reflects, “I wonder if I named the movie, or if I said that after I knew the name?” He thinks for a second. “I should see if IMAX will double my royalties,” he says laughing. “They’d probably be willing to do that no problem. They’ll probably triple them.”

Tickets for A Beautiful Planet are available online or at the box offices of the Lockheed Martin IMAX Theater at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Airbus IMAX Theater at the Steven F. Udvar-hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)