How John Glenn’s Encore Space Flight Lifted U.S. Spirits

Two cameras tell the tale of the first American to orbit Earth and his return to space 36 years later

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/2a/d02a8c3a-adb0-45fb-83f4-f3d5b14bf443/johnglenn_cameras.jpg)

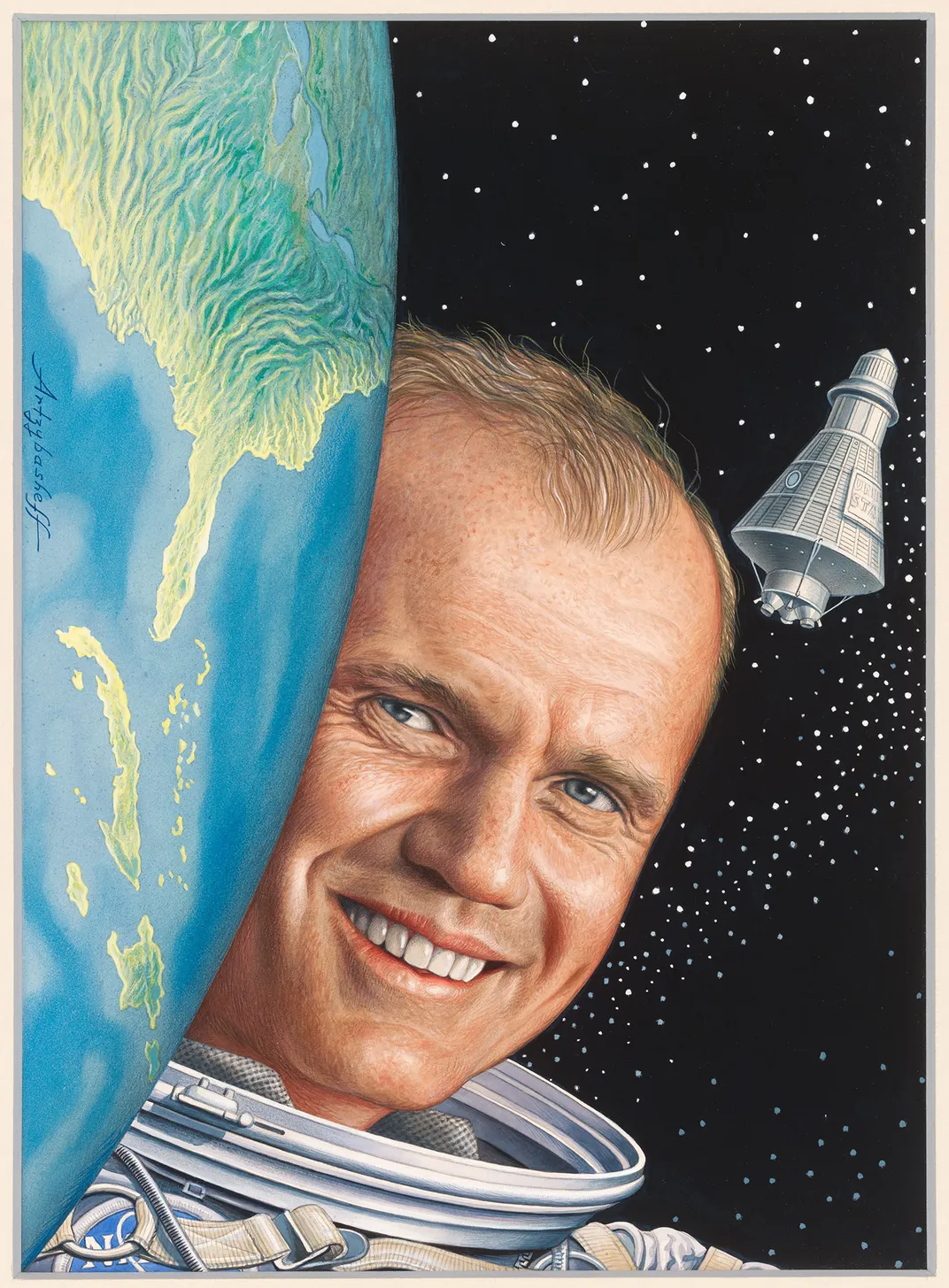

Before astronaut John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962, scientists thought a weightless man might not be able to swallow. They worried that his eyeballs might change shape and damage eyesight. Some feared that weightlessness might be so intoxicating that an astronaut might refuse to return to Earth. No one, but a few secretive Soviet scientists who had already sent two men into orbit, knew what to expect. After Glenn’s flight of less than five hours, all of these questions and many more had been answered by a U.S. Marine who was, at age 40, the oldest Mercury astronaut.

When Glenn first rocketed into orbit, America held its breath. Millions of Americans, from feeble World War I veterans to frisky first-graders, followed his original flight. The TV networks broadcast continuous coverage, including the sound of his surprisingly steady heartbeat. He was attempting something terrifying and wonderful, and awe was the order of the day.

On that flight, he took with him an Ansco Autoset camera that he bought in a Cocoa Beach drug store. NASA engineers hacked the camera so that he could use it wearing his astronaut gloves and attached a grip with buttons to advance the film and to control the shutter. With it, Glenn was the first to take color stills of Earth during his trip into space. That battered 35 mm camera is now held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., along with the Mercury Friendship 7 and other artifacts from Glenn's three-orbit mission.

After his return, fans filled the streets to watch parades in Washington D.C. and New York City. A joint session of Congress gave him a standing ovation. Noting the country’s affection for the famed astronaut, President John F. Kennedy quietly told NASA officials that Glenn’s life was too valuable to risk on another flight. With no opportunity to fly, Glenn left NASA in 1964, heading into business and politics.

Twenty years ago this month and 36 years after that first flight, U.S. senator John Glenn once again donned a spacesuit and soared into orbit. As before, on October 29, 1998, Americans were laser-focused on that venture when the 77-year-old grandfather flew aboard the space shuttle Discovery. And as before, he took a camera with him.

During his months of training, Glenn had enjoyed photography classes, especially after a geologist and geographer told the astronauts what kinds of images they would like to see. He treasured the opportunity to look at the Earth and loved using a Nikon digital camera. That sleek state-of-the-art (at the time) model, which other crew members used, was easily operated with interchangeable lenses. It also resides in the museum’s collections, along with the Space Shuttle Discovery and a host of other artifacts from that mission, known as STS-95.

For that mission, new generations cheered, as senior citizen Glenn again became America’s most-watched explorer. As Joe Dirik of the Cleveland Plain Dealer wrote, “It is certainly no knock on Ohio’s senior senator to note that he is not exactly a natural-born politician. He was always better at his first job. Being an American hero.”

Three years earlier, Glenn began his relentless battle to orbit the Earth again. As a member of the Senate’s Special Committee on Aging, he urged NASA head Dan Goldin to make him a guinea pig in a study of the similarities between the symptoms of aging and the effects of weightlessness. Goldin was skeptical, but eventually he told Glenn in January 1998, “You’ve passed all the physicals, the science is good, and we’ve called a news conference tomorrow to announce that John Glenn’s going back into space.”

Glenn wanted to show Americans that age need not be a restriction. “On behalf of everyone my age and older, and those who are about to be our age before too many years have gone, I can guarantee you I’ll give it my very best shot,” he said. He hoped such experiments could lessen “the frailties of old age that plague so many people.”

Glenn hadn’t told his family about his campaign until Christmas 1997. His wife and two middle-aged children were not thrilled. Images of the explosion of space shuttle Challenger after liftoff in 1986 haunted his son Dave, now a father himself.

But despite his family’s objections, Glenn planned to join six crewmates for the nine-day mission. In preparation, he underwent eight months of both physical and technological training. In one exercise, the septuagenarian did a nine- to 10-foot free fall into a pool while weighted down by a parachute and survival equipment.

On launch day, the crowd at Cape Canaveral included at least 2,500 journalists and more than 250,000 spectators—some of whom had been there on February 20, 1962, when he first journeyed into the unknown.

The Smithsonian’s Michael Neufield, senior curator of space history, recalls the excitement at the Air and Space museum that day: “They had TVs up, and they were just packed with people watching the launch. . . . Most of them were too young to ever remember the original [flight].” Neufeld thinks part of the interest sprang from Glenn’s age and the feeling “that you and I could deal with going into space if a 77-year-old guy could do it.” The museum took part in the Glenn hoopla by collecting more than 18,000 electronic postcards addressed to the senator/astronaut from people all over the world. “Thank you so much for the reminder that the only limits in this life are the ones you impose upon yourself—that with hard work and a little luck anything is possible,” said one. Another noted that “your mission is a great inspiration to the kids I mentor at Gen Milam School in Grand Prairie, TX.”

Glenn’s Discovery crewmates were Commander Curtis L. Brown; pilot Steven W. Lindsey; mission specialists Scott E. Parazynski, Stephen K. Robinson, plus astronaut Pedro Duque from Spain and payload specialist Chiaki Mukai from Japan. But for most Americans, the other astronauts’ names were mere footnotes to Glenn’s. After 90 successful shuttle flights, the public had become blasé about the hundreds of men and women who climbed aboard the spacecraft.

Glenn participated in several shuttle-to-Earth communication events with other crew members. He answered students’ questions, spoke to Japan’s prime minister, did a live interview with the Tonight Show’s Jay Leno, and took part in NASA’s 40th anniversary luncheon in Houston by speaking to Goldin and newscaster Walter Cronkite, who had anchored coverage of Glenn’s first flight and joyously had come out of retirement to cover this flight for CNN.

In Glenn’s Mercury capsule, there were no bathroom facilities, so he wore a condom connected to rubber tubing and a collection bag attached to the back of one leg in case he needed to urinate. Discovery’s facilities offered privacy and relative ease in eliminating bodily waste. During liftoff and landing, Glenn and his crewmates wore diapers to accommodate emergencies.

While in orbit, Glenn underwent many tests. Ten blood samples and 16 urine samples were taken to gauge the effects of weightlessness. Each day, he completed a back pain questionnaire, and he and crewmate Mukai tracked their food consumption. Even when he slept, Glenn was tested. At one designated bedtime, he swallowed a thermistor capsule that recorded his body’s core temperature. During some sleep periods, he and Mukai wore an electrode net cap connected to a device tracking respiration, body and eye movements, muscle tension and brain waves. To judge how astronaut sleep disturbances affected cognitive skills, both underwent computerized exams.

John Charles, who was the flight’s project scientist and is now scientist in residency at Space Center Houston, says no huge discovery emerged from Glenn’s tests because it was impossible to make generalizations based on samples from a single elderly American. However, Charles says examination of the crew’s readings did generate one unexpected conclusion: Despite a dramatic age difference (the oldest of his crewmates was 9 when Glenn orbited in 1962), his readings were remarkably similar to those of his colleagues.

Discovery’s mission was not limited to medical tests. The crew conducted more than 80 experiments in all. The biggest was launching and retrieving Spartan, a satellite that studied solar winds. When the flight ended November 7 with a safe landing at Kennedy Space Center, Glenn could have been carried from the shuttle to minimize the shock of a return to normal gravity. He insisted on walking, but later admitted that during landing, he suffered repeated vomiting, delaying the crew’s emergence from Discovery.

While some critics saw the senator’s second flight as a NASA publicity stunt, Glenn again felt American adulation through letters, requests for appearances and parades in his honor. Some children felt a special affection for this grandfatherly figure, while many senior citizens found his achievement inspiring. Glenn again found himself at the center of a New York City tickertape parade before a sparce crowd of a mere 500,000—compared with his 1962 parade, which attracted four million. Nevertheless, as the New York Times reported, “There were many cheerful scenes of people enjoying themselves during their brush with history. Fathers hoisted children on their shoulders, children waved American flags and people lined up to buy commemorative T-shirts.”

In orbit, Glenn had repeated the words he had used in 1962 to describe weightlessness, “Zero-g and I feel fine.” He watched the beautiful planet below, an image he had thought he would never see again with his own eyes, and a tear materialized in his eye—and just settled there. “In zero gravity,” he recalled later, “a tear doesn’t roll down your cheek. It just sits there until it evaporates.”

John Glenn: America's Astronaut

In February 1962, he became the first American to orbit the Earth. Since then John Herschel Glenn Jr. has stood in the popular imagination as a quintessentially American hero. In John Glenn: America's Astronaut, a special edition e-book featuring 45 stunning photographs as well as a video, Andrew Chaikin explores Glenn's path to greatness.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)