Two Museum Directors Say It’s Time to Tell the Unvarnished History of the U.S.

History isn’t pretty and sometimes it is vastly different than what we’ve been taught, say Lonnie Bunch and Kevin Gover

:focal(3616x1184:3617x1185)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/bd/cabdc41e-ebe1-4f11-bb76-9db6ca2de197/panel_20180303_mmmm_304.jpg)

“History matters because it has contemporary consequence,” declared historian Jennifer Guiliano, explaining to an audience how stereotypes affect children of all races. “In fact, what psychological studies have found, is when you take a small child out to a game and let them look at racist images for two hours at a time they then begin to have racist thoughts.”

The assistant professor affiliated with American Indian Programs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis went on to explain what that means to parents who have taken their kid for a family-oriented excursion to a sporting event with a racist mascot.

“We’re taking children who are very young, exposing them to racist symbology and then saying ‘But don’t be a racist when you grow up,’” Guiliano says. “This is the irony of sort of how we train and educate children. When we think about these issues of bringing children up, of thinking about the impact of these things, this is why history matters.”

Guiliano was among the speakers at a day-long symposium, “Mascots, Myths, Monuments and Memory,” examining racist mascots, the fate of Confederate statues and the politics of memory. The program was held in Washington, D.C. at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in partnership with the National Museum of the American Indian.

Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the African American History museum, says this all came about after a conversation with his counterpart Kevin Gover at the American Indian museum. Bunch says he learned that the creation of Confederate monuments and the rise of racist Indian mascots in sporting events occurred during the same period in American history, between the 1890s and 1915. This gathering was one way to help people understand the how and why between that overlap.

“It’s all about white supremacy and racism. The notion of people, that you’re concerned about African-American and Native people, reducing them so they are no longer human,” Bunch explains. “So for African-Americans these monuments were really created as examples of white supremacy—to remind people of that status where African-Americans should be—not where African-Americans wanted to be. For Native people, rather than see them as humans to grapple with, reduce them to mascots, so therefore you can make them caricatures and they fall outside of the narrative of history.”

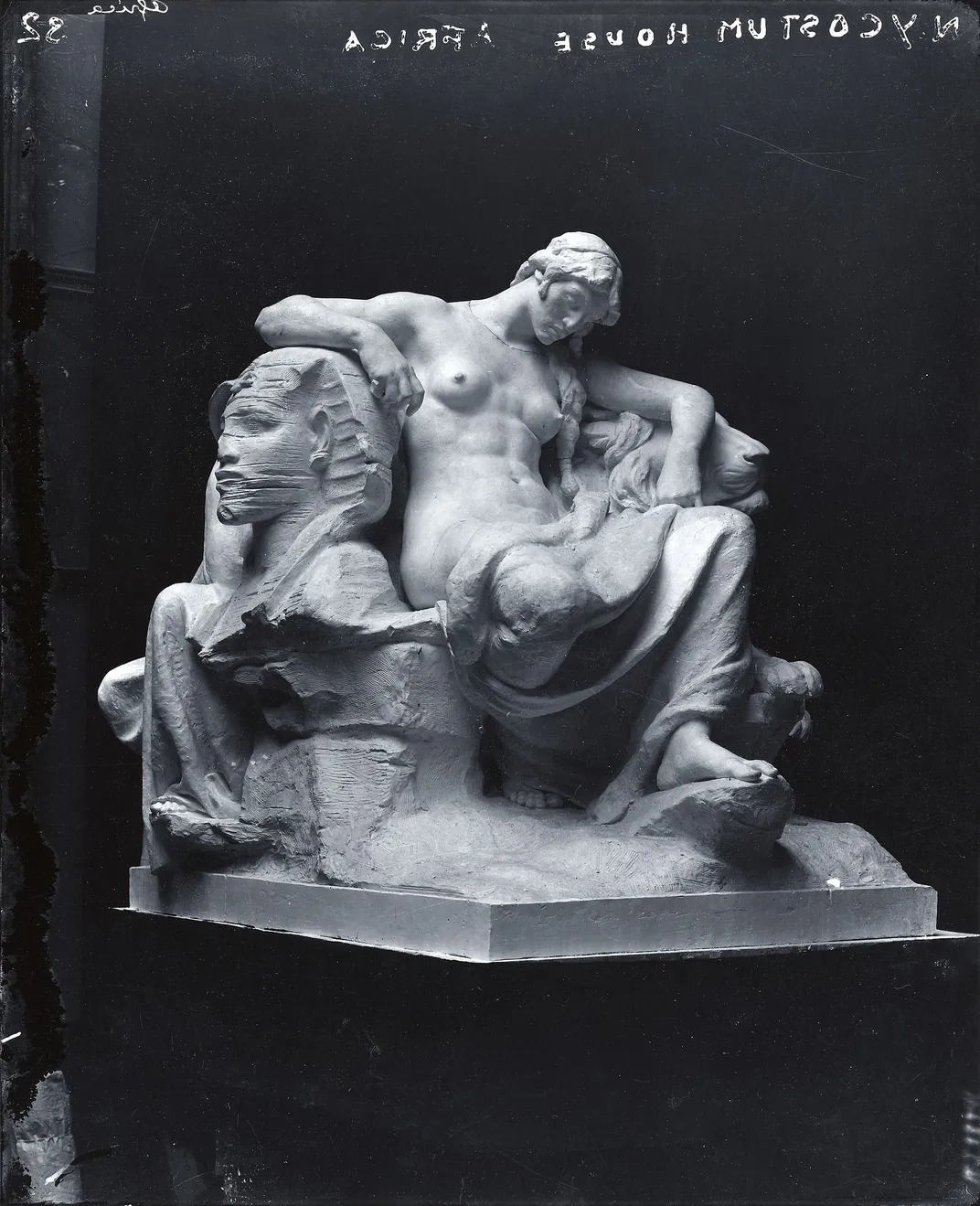

American Indian museum director Kevin Gover took the audience on a riveting trip through several 19th-century monuments, including four by Daniel Chester French that adorn the exterior of the 1907 Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, now home to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. The French sculptures, female figures representing the four continents and entitled, America, Asia, Europe and Africa, says Gover, send disturbing messages to the public.

“You can see that America is rising from her chair, leaning forward, looking far into the distance. The very symbol of progress. Bold. Surging. Productive. . . . Behind America is this depiction of an Indian. . . . . But here, what we really see is this Indian being led to civilization,” he says.

Gover describes the Europe figure as regal and confident, with an arm resting on the globe that she conquered. The figure representing Asia, he explains, is depicted as inscrutable and dangerous, resting on a throne of skulls from those murdered throughout the Asian empire. Then, there’s the female figure representing Africa.

“As you can see, Africa is asleep. It’s unclear whether she is exhausted or merely lazy. The lion to her left is also asleep. To the right is the Sphinx, which is of course in decay, indicating that Africa’s best days were behind her,” Gover says, adding that the sculptor was racist, but no more so than the rest of the American culture at that time that agreed with these stereotypes. Near the end of his career, French designed the statue of Abraham Lincoln that sits within the Lincoln Memorial, just a short walk from where the symposium was held.

Such public monuments were created in the same period that mascots came into being, such as the Cleveland Indians baseball team which got its name in 1915. Gover notes that it is one of the few mascots that became more racist over time, culminating in the insanely grinning, red-faced, Chief Wahoo. Beginning next year, Major League Baseball says the team will stop using what many find to be an offensive logo on its uniforms, saying that the popular symbol is no longer appropriate for use on the field.

Most universities, have stopped using Native American team names, including the University of North Dakota which changed its name from the Fighting Sioux to the Fighting Hawks in 2015.

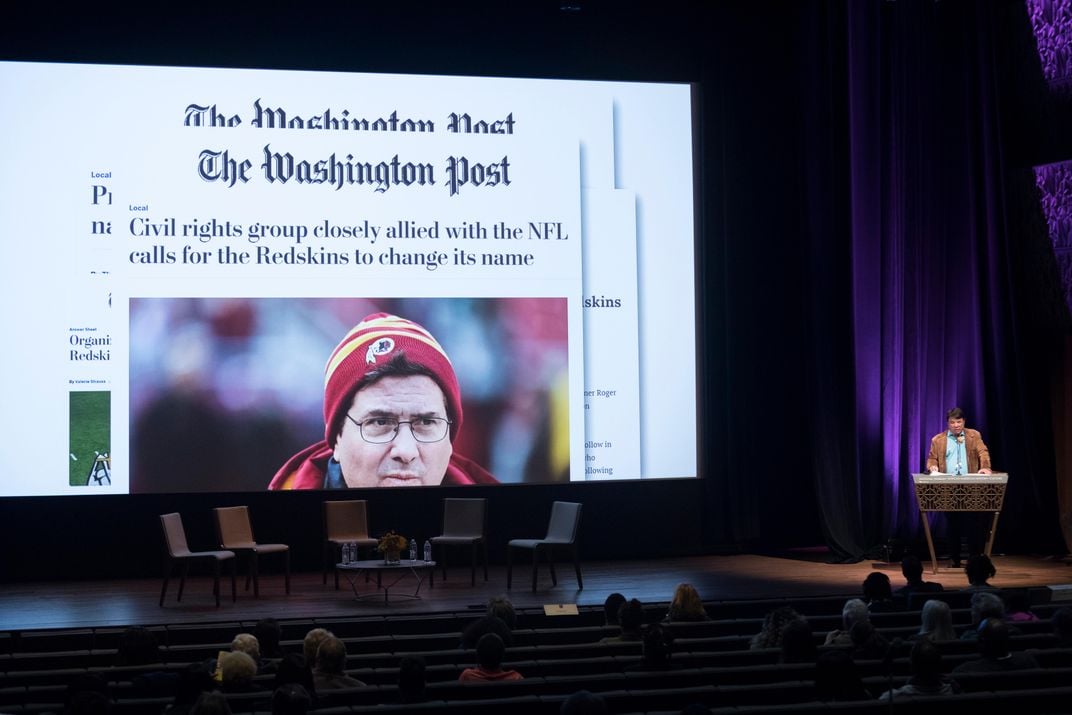

But many other teams, including the N.F.L.’s team in Washington D.C., have resisted increasing pressure to do so. Gover has been vocal in his opposition.

Team owner Daniel Snyder has vowed never to change its name, despite a suggestion from President Barack Obama that he do so, claiming it is actually a tribute. In fact, a 2016 Washington Post poll found that nine out of ten Native Americans were not bothered by the name activists refer to as the R-word. Ray Halbritter, whose Oneida Indian Nation is the driving force behind the Change the Mascot campaign, explains why he finds the term offensive.

“Racism and bigotry are not simply expressions of hate and animosity. They are instruments of broad political power. Those with political power understand that dehumanizing different groups is a way to marginalize them, disenfranchise them, and keep them down,” Halbritter says, adding that the name originated with one of the team's previous owners, George Preston Marshall, who held segregationist views. He notes that the team was the very last to sign African-American players, and that its name remains offensive to many, but particularly to Native Americans.

“This team’s name was an epithet screamed at Native American people as they were dragged at gunpoint off their lands,” Halbritter explains. “The name was not given to the team to honor us. It was given to the team as a way to denigrate us.”

Historian Guiliano pointed out that at the start, before 1920, colleges and universities as well as sports teams began taking on names ranging from the “Indians” and the “Warriors.” But she says they didn’t become tied to a physical mascot, performing and dancing until the late 1920s and early 1930s.

“When you look across the nation, there’s sort of this groundswell beginning in 1926, and really by the early 1950s it proliferates everywhere,” Guiliano explains. “When those images are getting created. . . they’re doing it to create fans, to bring students to games, to get donors. But they’re drawing on a lot older imagery. . . . You can literally take one of these Indian-head images we use as mascots and you can find newspaper advertisements from the early 1800s when they’re using those symbols as advertisements for the bounties the federal government put on Indian people.”

She says the federal government had a program where it offered rewards for scalps for men, women and children, and the Indian-head symbols were signs that you could turn in your scalp here and be paid.

The movement to take down Confederate monuments is obviously mired in the pain of the memory and lingering effects of slavery, and has become more urgent as of late. Such was the case when white supremacists gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of an equestrian statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, clashing with anti-racist protestors and killing a woman in the process.

The symposium’s keynote speaker, American University professor and director of the anti-racist research and policy center, Ibram X. Kendi, described what it was like moving from Queens, New York, to Manassas, Virginia, as an African-American high school sophomore. He remembers tourists swarming to Manassas National Battlefield Park to relive Confederate victories. Appropriately, Kendi titled his keynote “The Unloaded Guns of Racial Violence.”

“I started to feel unsettled when people who despised my existence walked around me with unloaded guns. I knew these guns could not kill me,” Kendi explains. “But my historical memory of how many people like me these guns had killed sapped my comfort, injected me with anxiety, which sometimes went away. But most times it turned into fear of racial violence.”

He says he thought about what it felt like to be surrounded by so many Confederate monuments, and what it felt like to literally watch people cheer for mascots that are a desecration of their people. He also considered the relationship between racist ideas and racist policies.

“I found . . . that powerful people have instituted racist policies typically out of cultural, political and economic self interest. And then those policies then led to the creation of racist ideas to defend those policies,” Kendi says. “Historically, when racist ideas won’t subdue black people racial violence is oftentimes next. . . . So those who adore Confederate monuments, those who cheer for the mascot are effectively cheering for racial violence.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/27/fa27c5ff-5e29-4d26-9166-4edb548beef6/panel_20180303_mmmm_037.jpg)

Some at the symposium wondered whether Confederate monuments should be removed or covered, as they have been in some of the nation’s cities. But the African-American museum’s director Bunch isn’t sure that is the way to handle the controversy.

“I think as a historian of black America whose history has been erased I don’t ever want to erase history. I think you can prune history. However, I think the notion of taking down some of the sculptures is absolutely right. . . . I also think it is important to say some of these monuments need to stand, but they need to be reinterpreted,” Bunch says. “They need to be contextualized. They need people to understand that these monuments tell us less about a Civil War and more about an uncivil peace.”

One way to do that, Bunch said, would be to place them in a park, as Budapest did after the fall of the Soviet Union. Gover doesn’t think that’s the way to go about it. But he thinks events like this one are part of a growing movement, in which institutions like this take a more active role in understanding the nation’s history differently.

Asked if the symposium represented a new path forward for museums to be more involved in hot-button topics of the day, Gover agreed that museums have much to share on these issues.

“The obvious thing to me was that when you have a platform like a Smithsonian museum dedicated to the interest of Native Americans you are to use it to their advantage and tell stories in ways that are advantageous to them. I know you know Lonnie (Bunch) feels the same way about the African American museum,” Gover says. “This notion that museums and scholars and experts of all types are objective, that’s nonsense. None of us is objective and it’s just nice that now some of these institutions are able to produce excellent scholarship that tells a vastly different story from what most Americans learn.”

Gover says some museums have to live under the demand of telling a pretty story. But he thinks now institutions that aren’t associated with a particular ethnic group, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, will now start moving in the same direction as the Native American and African American institutions.

“When you’ve created an American Indian and an African American museum, “Gover says with a laugh, “what Congress was really saying is, ‘Okay. Look. Tell us the truth.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)