Two Smithsonian Scientists Retrace the Mysterious Circumstances of an 1866 Death and Change History

Did the 19th-century naturalist Robert Kennicott die of his own hand?

:focal(1142x450:1143x451)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/ba/86ba6708-9c5f-4ae0-803e-1740ebe414d2/mah43604crop.jpg)

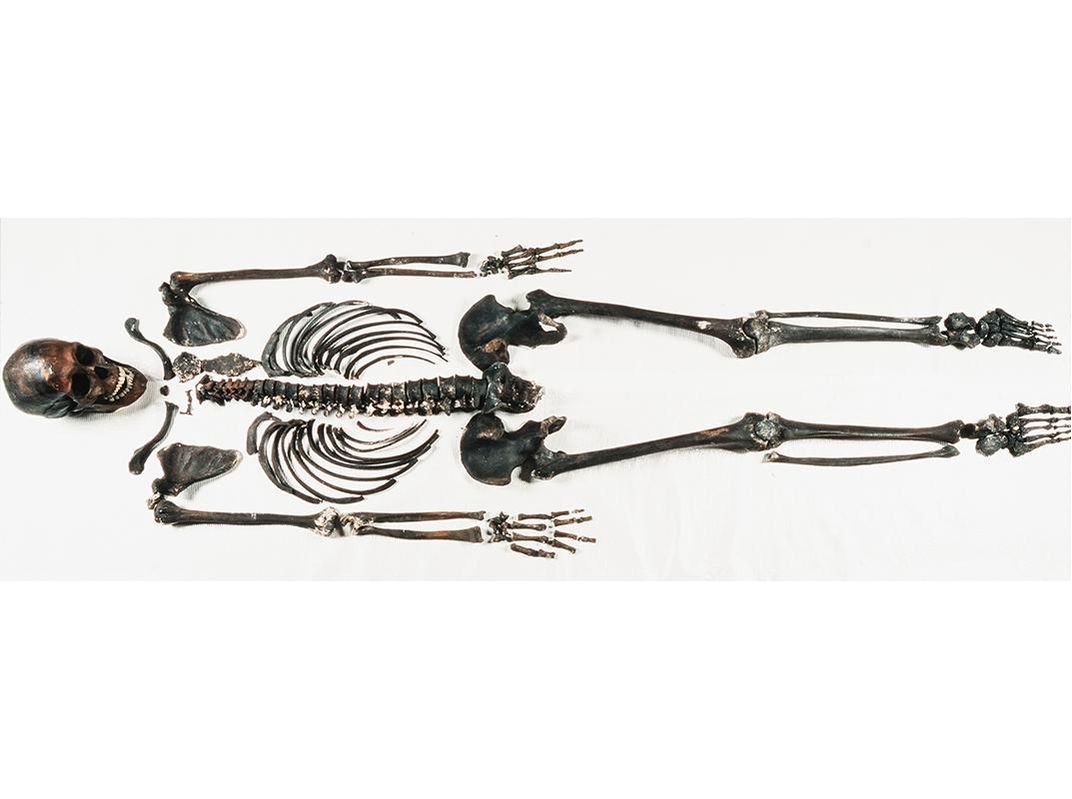

It all began with the opening of the cast iron coffin. Because it was an air-tight environment, the scientists hoped to find Robert Kennicott’s body in good condition, with well preserved clothing, soft body tissue, hair, fingernails and toenails. All of those things would allow for a variety of chemical tests to be done, and to answer questions that the skeleton alone could not.

Kennicott was born in 1835, and grew up on the prairie north of Chicago. While he was still a teenager, and the Smithsonian was only six years in the making, he was already sending extensive specimens to the Washington, D.C. institution.

By the time Kennicott was 21, he was one of the founders of the Chicago Academy of Sciences, and Spencer Baird, the Smithsonian’s assistant secretary, was training him and recruiting him to begin collecting specimens for the institution.

Kennicott’s skeleton, now held in the research collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, along with some of the many objects he collected, will go on view in the upcoming exhibition “Objects of Wonder,” opening March 10. The museum’s research collection is the most extensive in the world, and contains more than 145 million artifacts and specimens. Kennicott contributed hundreds of pieces during his short life, and the exhibition examines how scientists use the museum’s collections to illuminate understanding of nature and human culture. But Kennicott will be there also, in bones, if not in spirit, too.

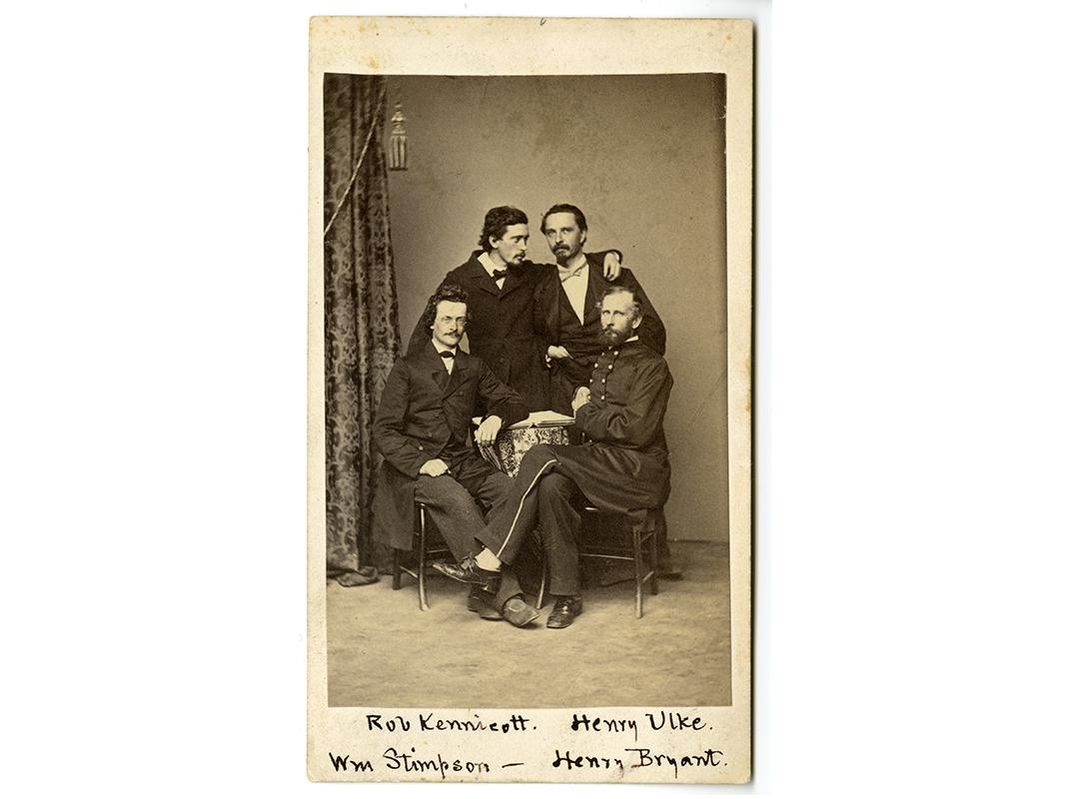

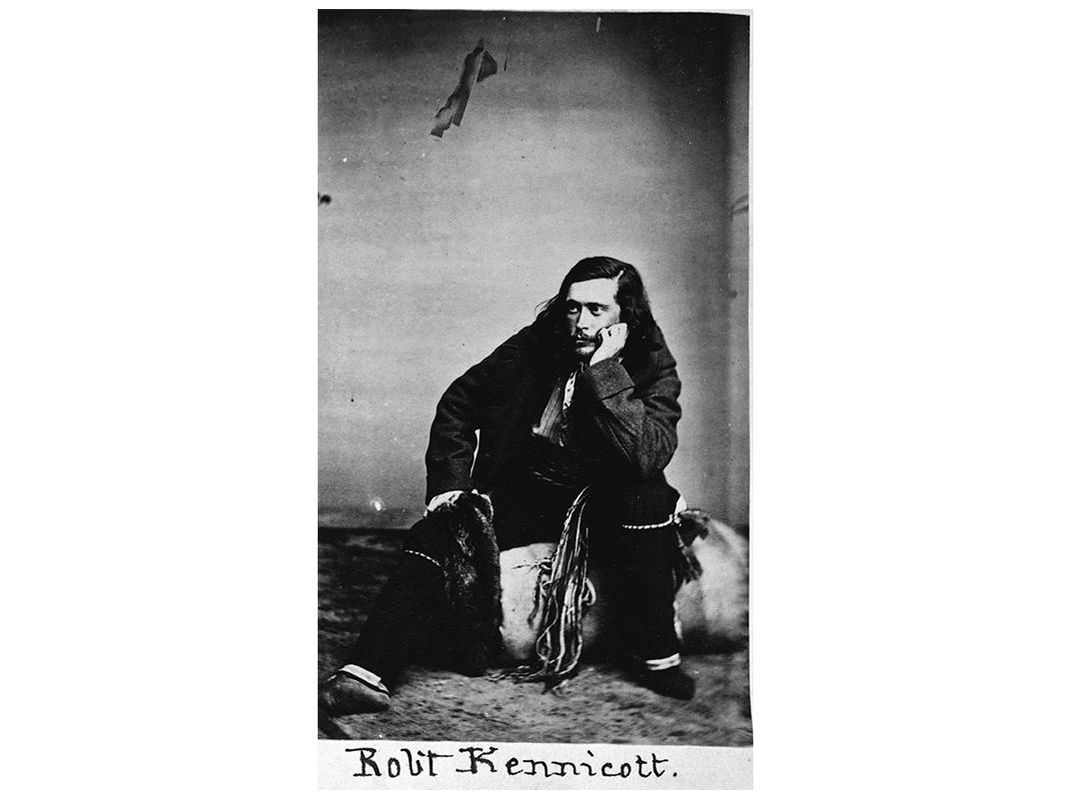

In photos, Kennicott has flowing hair, piercing eyes and strong features. He stares intently into the camera, wearing what looks like trapping gear—or thoughtfully off to the side in his Western Union uniform.

If a movie were ever made about the life of the young swashbuckling scientist, the consensus around the physical anthropology department at the museum is that the moody and intense actor, Johnny Depp, should play his character.

“All of the women in our office believe that,” laughs Kari Bruwelheide, a physical and forensic anthropologist at the Natural History Museum. She sits in her office, surrounded by various skeletons laid out neatly on a long table, some still in labeled plastic bags. “Robert was a special person, and somewhat emblematic of curators at the Smithsonian even today, because he was so dedicated to his work. It was everything to him. It was not necessarily a job but a way of life that began when he was just a child, and continued until his death at the age of 30.”

Bruwelheide says the objects Kennicott collected are still used today to conduct research.

“It’s like everything comes full circle and it’s a wonderful story,” she muses. Bruwelheide and her colleague, Doug Owsley, curator and the museum’s division head for physical anthropology, were tasked at the request of Kennicott’s family and the museum, with finding out how Kennicott died in 1866. Owsley and Bruwelheide’s work on the Kennicott case is being published this month in a volume by Cambridge University Press.

There were rumors that he had committed suicide, but Kennicott’s family wasn’t so sure. In 2001, Owsley and Bruwelheide traveled to his boyhood home, The Grove in Glenview, Illinois, to open Kennicott’s casket and determine the cause of his death. The Grove is now a national landmark education and nature center. Owsley and Bruwelheide were excited to help solve a mystery involving a man who contributed so much to science in life—and in death.

“He epitomizes the young person who is enthralled with natural history and follows his passion and is mentored by scientists which is exactly what we do today,” Bruwelheide says. “His story took place at the very origins of the Smithsonian Institution.”

Kennicott came to the Smithsonian in 1858, and lived at the institution’s iconic red brick castle on the National Mall, the Smithsonian’s only building at the time. He lived with other naturalists and they formed a fraternity-like group called the Megatherium Club. Using the imaginary call, "How! How!" of their mascot, an extinct ground sloth, they played games at night among the collections, running three-legged sack races through the great hall, drinking ale in the cellar and sharing smoked oysters. The club's motto was "Never let your evening's amusement be the subject of your morning's reflections."

Kennicott, one club member recalled, was "always bubbling over with fun."

A year later, Baird sent Kennicott on a three-year mission through central British America (now Canada) that ended at Fort Yukon in western Russian America (now Alaska). He traveled by dogsled, canoe and on foot, and brought back hundreds of animal and plant specimens, as well as Native American clothing and weapons, and compiled some of the earliest dictionaries of tribal languages. Kennicott’s exploration and the papers he sent home after his final expedition played a major role in the United States’ eventual purchase of the Alaskan Territory.

“He collected everything that fascinated him, from mammals (230) to birds (282) to eggs to fossils. . . . He was just kind of the Renaissance naturalist of that time period,” says Bruwelheide, who calls the Kennicott case “the most complicated and interesting mystery we have ever encountered.”

The mystery begins with Kennicott’s death on May 13, 1866. He had been on another long mission to the Yukon—this time for the Western Union Telegraph. He was the only person who had lived in Russian America, and was to help that company find a route to lay a cable connecting the United States with Europe via the Bering Strait. Kennicott and two fellow naturalists also planned to collect rare specimens, but they arrived just below the Arctic Circle as winter began in 1865. They made a grueling trip to Fort Nulato on the Yukon River, 500 miles from any other fort, in temperatures as low as 60 below zero.

By spring, Kennicott intended to begin his own work as a naturalist. But he didn’t show up for breakfast that day, and his men found him dead by the bank of the river near the fort. Rumors began that he had committed suicide by swallowing the strychnine he often carried to preserve specimens. His friends spent eight months on a journey to bring Kennicott’s body back. He was buried in January 1867 at The Grove, in an airtight metal coffin.

Owsley and Bruwelheide, two of the world’s foremost experts in examining the contents of iron coffins, were the obvious choice for solving the mystery. Not only had the two already helped identify those killed in the Waco siege and in the terror attacks of 9/11, they’ve been involved with mummies, Civil War soldiers and are currently working on early Jamestown inhabitants.

“I think it is absolutely one of our most challenging cases because it required so much research. This continued tracking of all of these leads, pulling information out of letters, it has continued for years. It’s very methodical and very systematic,” Owsley says. “I can’t think of any investigation that has been so comprehensive. It is how we work. We don’t take on every project we’re asked to investigate as we do it so carefully and very methodically. But from my perspective, we look at it as to whether it is a good question.”

The scientists had Kennicott’s bones but they also had a huge trove of historical information thanks to Sandra Spatz Schlachtmeyer. The skilled archivist amassed so much historical information about Kennicott, from eyewitness accounts of his death to communications from his family and friends, that she was inspired to write a book, A Death Decoded: Robert Kennicott and the Alaska Telegraph. Her work gave the anthropologists an extraordinary tool in helping to decode the physical findings they had to work with.

“Her research was incredibly important to our final analysis,” Bruwelheide says.

The faceplate on Kennicott’s airtight coffin unfortunately had been broken, and although his face could be seen, it had been partially filled with water.

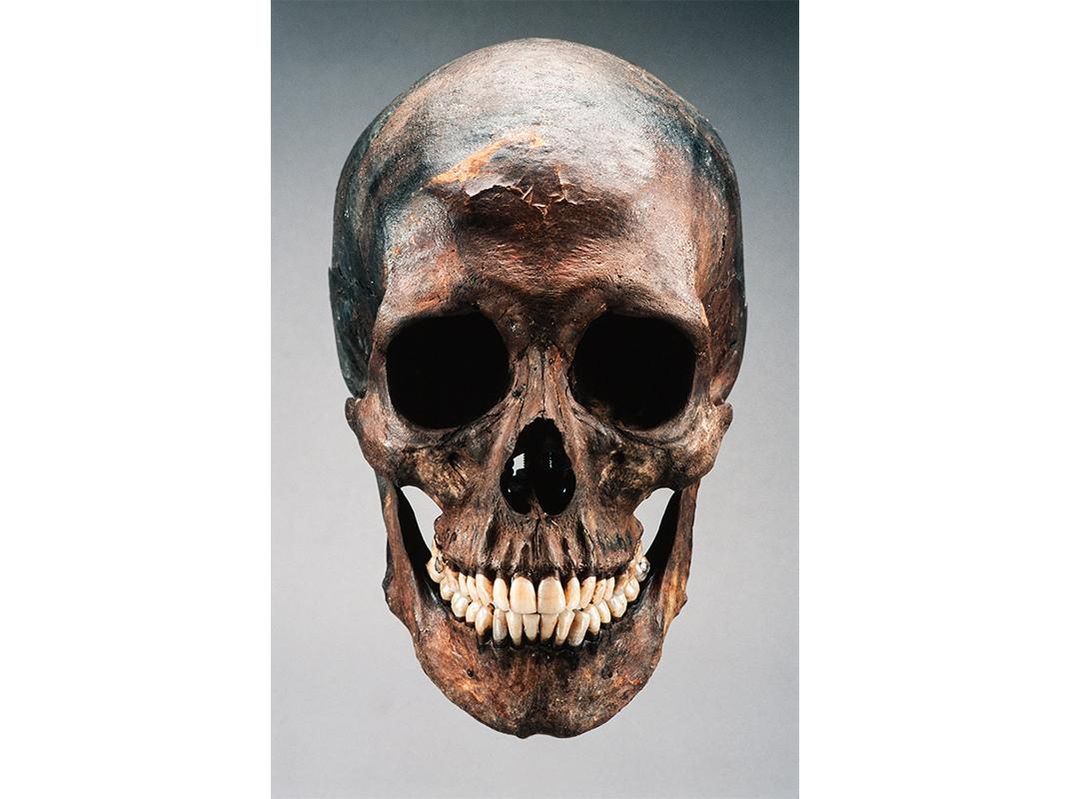

“But when we first opened it, we did notice there was a lot preserved. All that fabulous hair. It’s hard to describe seeing something for the first time after 100 years,” Bruwelheide recalls. “In this case, the clothing that he was buried in was still mostly intact. You could see the gold that was in the buttons on his coat. The moment of opening it up was really an exciting moment with the hope that we could answer the question that the family wanted us to answer—what was his cause of death?”

Among the questions the forensic anthropologists and two pathologists on the case had to answer, were if Kennicott hadn’t committed suicide, what types of medical conditions might he suffer from?

Owsley notes that the two years of research uncovered information he calls “critical” to understanding Kennicott’s childhood history as well as evidence of fainting spells he had had that pointed to possible heart disease. Also, eyewitness accounts of the condition of Kennicott’s body when it was found by the river, discounted the rumors that he had poisoned himself with strychnine.

“The body was found 500 yards from the fort. His positioning—how the brim of his hat was resting against the top of the head—his arms were folded,” Owsley explains. “There was no comment on the disturbed movement of the earth around him. If you had purported strychnine poisoning, really strong muscle spasms would have been in evidence.”

It had been rumored that Kennicott had rheumatic fever, which could lead to the scarring of heart tissues. Bruwelheide says it is also a cause of death for young adults who suffered from that illness as children. She hoped that the tissues of Kennicott’s heart were preserved, but they were not. Then the scientists moved to chemical analysis.

“The skeleton itself was beautifully preserved. He had no fractures, no healed injuries in life. He was described as relatively frail, but he had excellent bone density and excellent muscle markings,” Bruwelheide says, but adds that it did not offer any clues to his cause of death. “We decided to do several tests looking at the composition of his bones, his hair, his fingernails and his toenails to see if we could identify any poisons that might correlate with the rumors of suicide or more importantly, the use of medications in his lifetime.”

Archival research of communications between Kennicott and his family indicated that he suffered from fatigue, heart conditions and depression. That meant he began taking mercury at a young age, which was a common treatment for depression at the time. Bruwelheide pointed out that President Abraham Lincoln also took mercury, which stimulated bodily organs and increased the heart rate though it is known today as a toxin.

“A lot of the techniques we used in our forensic casework are the same ones that you would use to look at materials that are potentially hundreds of years old, things like analyzing the hair for certain drugs and heavy metals,” Bruwelheide explains, adding that they were looking not only for mercury but the strychnine Kennicott was known to carry on his collecting trips to get specimens of the animals. It was used as an insecticide to preserve the skins on the hides. At the time it was also used as a medical treatment in various forms to treat several of the conditions Kennicott said that he suffered from in his letters. Kennicott’s father was a medical doctor who had prescribed strychnine to other patients, and it was known that Kennicott carried a personal vial with him.

Lead was also a big health factor in the 1800s as it is today, and can be ingested accidentally or it enters the body through other ways. Bruwelheide says in addition, scientists looked at arsenic, a toxin that was not only common in medical use at the time, but more importantly was used by Kennicott and his men to preserve specimens. So the scientists had to decipher toxins he was exposed to during his life and discover whether they contributed to his death, as well as figure out whether they were used to preserve Kennicott’s body for a journey of thousands of miles back to Illinois.

“What we found was there was a high level of mercury—not enough to contribute to his death but he was ingesting mercury during his life. . . .You have few opportunities to evaluate medical use in the 19th century and this was a rare test where we could actually do that,” Bruwelheide says. “The lead contamination was post-mortem. He did have extremely high levels of lead but we believe that came in through the coffin environment.”

Not only were coffins at that time painted on the inside with a lead white paint, but the Western Union uniform Kennicott was wearing and such coats and blankets at the time were treated with lead acetate as a water proofing mechanism. The scientists also discovered that Kennicott had high levels of strychnine, particularly in his brain tissue, and found that he had ingested it during his lifetime. But the peaceful position of his body when it was found made it unlikely that he had used strychnine in a suicide.

“Strychnine was present, but it wasn’t the factor responsible for his death,” Owsley says with conviction.

The descriptions of Kennicott’s behavior prior to his death were very consistent with periodic evidence related to heart disease. Just before he left San Francisco for Alaska on his final expedition, Kennicott lost consciousness briefly. A colleague, William Dall wrote that: “while sitting on his bed, talking to one of his companions, the color suddenly left his cheeks and he fell back pulse less for several minutes on his bed.” That condition, Bruwelheide explains, is suffered by people with heart disease, and usually results in eventual death.

“So those historic incidents we were able to interpret and piece together . . . determine that it was heart conditions that eventually led to his death,” Bruwelheide says. “That’s not to say he didn’t ingest the toxins during his life, but he had no intention—we believe—of ending his life.”

“This is what I love about this work! It’s really a mystery that you are tasked to solve and you don’t know what types of analysis you are going to need to solve the case,” Bruwelheide explains. “You go down various avenues, not just looking strictly at bone studies or at chemical analysis, but you incorporate historic documents, historic research . . . even mortuary practices and you combine all of these different kinds of information to solve this mystery you are presented with.”

Owsley stresses that without the huge innovations in their field, some of the research they are doing now, including examinations of the 17th-century settlers in Jamestown, would be impossible.

“We’re able to figure out their diet, whether they were born and raised in Europe and came over here and promptly died, whether someone born over there came here and lived for 20 years. We can track people back to their homes by testing oxygen isotopes, determine their drinking water, how much wheat they ate versus corn,” Owsley says. “It’s just a wealth of knowledge we have today—the ability to image and different types of radiography—so unbelievable! It’s a world that when you really get into it – that’s fascinating.”

“Objects of Wonder: From the Collections of the National Museum of Natural History” is on view March 10, 2017 through 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)