The Unbreakable Spirit of American Paralympians Is Embodied in These Artifacts

Smithsonian’s Sports History collections honor the indomitable innovators of the Paralympic community

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/f3/64f39e59-0973-4b06-93f0-22d8b6eeb269/image_5.jpg)

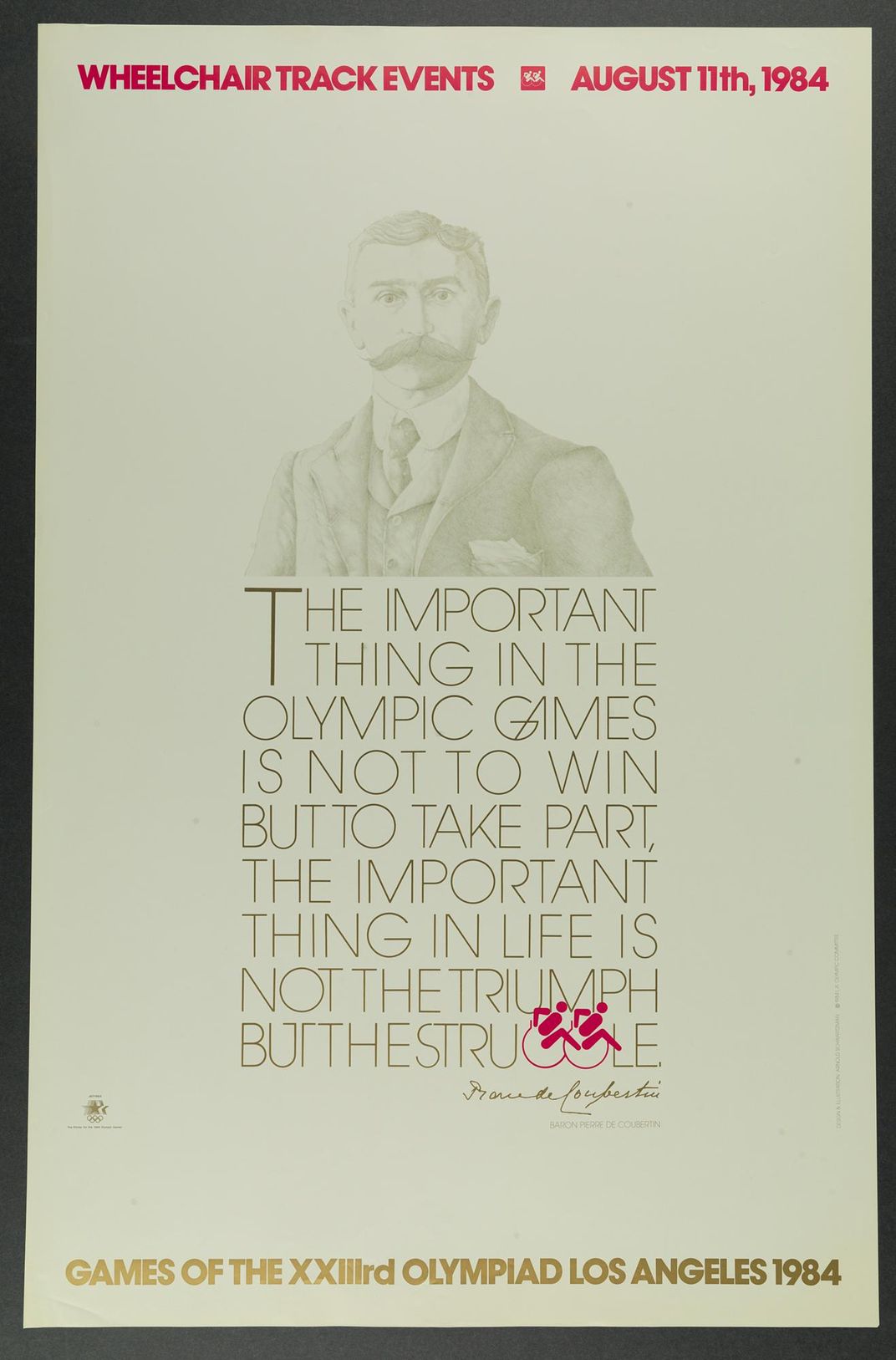

For those not familiar with the Paralympic Games, they are the Olympic competition for athletes with physical disabilities. The word “Paralympic” comes from the Greek prefix “para-,” which means beside or alongside. Since the first Summer Paralympic Games were held in Rome in 1960, both Olympic and Paralympic Games have been held within a few weeks of each other.

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, those of us in charge of the sports history collections have the opportunity to collect objects from some of these unique and gifted athletes.

Often referred to as adaptive athletes, these competitors are constantly having to alter themselves, their equipment and/or their prosthetics to their sport and to their specific disability. Most would argue that their disability is not a serious impediment, and all enjoy the chance to compete on as level a playing field as possible.

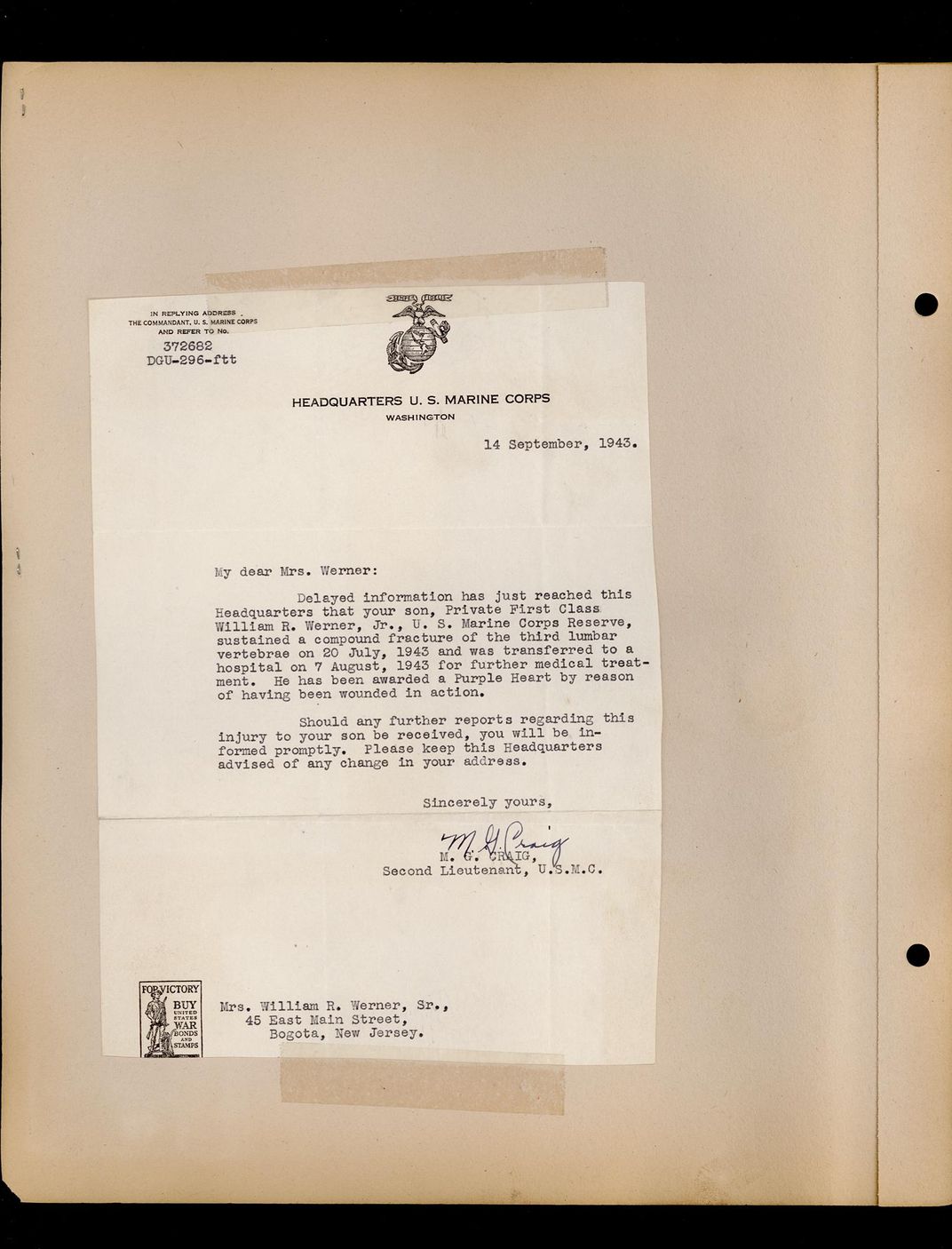

Always looking for unique collecting avenues to pursue, the sports history division achieved a Paralympic high point in 2013 with the donation of a championship jacket and a scrapbook containing personal items from a soldier-athlete’s service during World War II, including a transformative letter home.

The official Marine Corps letter was dated September 14, 1943 and read:

“My dear Mrs. Warner: …your son, Private First Class William R. Werner, Jr. U.S. Marine Corp Reserve, sustained a fracture of the third lumbar vertebrae on 20 July 1943 and was transferred to a hospital on 7 August 1943 for further medical treatment.”

Werner had been shot in the back by a Japanese sniper in the battle of New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. Paralyzed from the waist down, Werner’s journey told a story of determination and a strong desire to live his life without limits.

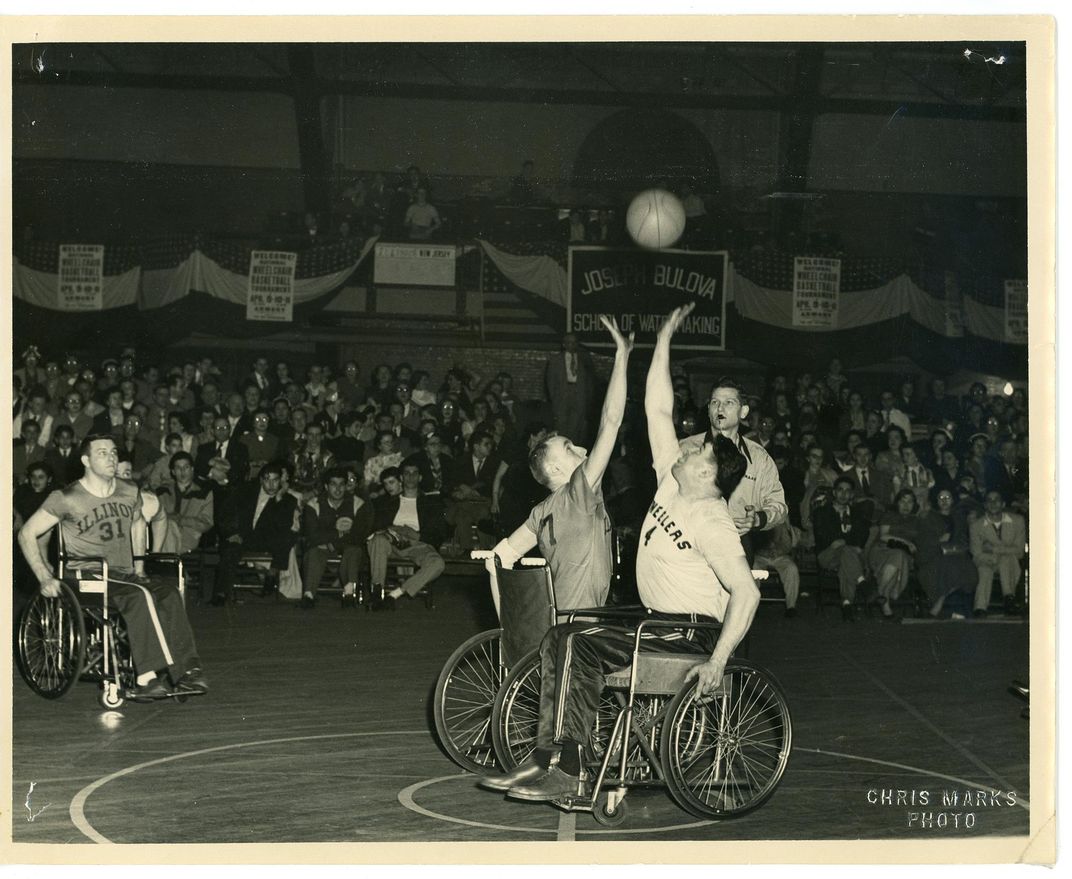

The scrapbook’s letters and photographs reveal that after his injury, Werner was sent to a rehabilitation hospital in California where sports participation was used early on in his treatment. A gifted athlete in high school, Werner’s athleticism made him the perfect candidate for a new series of rehabilitation programs initiated by the federal government. Wheelchair basketball seemed to be the sport of choice among many of the veterans because it was closely patterned after the game that they had played before their injuries.

News clippings and photographs reveal that Werner joined the New Jersey Wheelers, one of the first organized wheelchair basketball teams on the East Coast. Under Werner’s leadership, the Wheelers won the 6th Annual National Wheelchair Basketball Tournament in 1954. The slogan for the tournament was “Ability Not Disability Counts!” and included the organization’s purpose: “to foster and promote wheelchair basketball as an aid to the physical and social readjustment of the handicapped.” This revolutionary idea was taking hold across America, and eventually led Werner Ray to compete in the first Paralympic Games in 1960.

The Paralympics are a direct descendant of the Stoke Mandeville Games for the Paralyzed founded in 1948 by Sir Ludwig Guttman, a neurologist working with paralyzed veterans in England. These Olympic-style events coincided with the opening of the 1948 Summer Olympic Games in London, and gave athletes with spinal cord injuries the chance to compete. The first games involved an archery contest between 16 athletes. With the success of these first games, Guttman decided to make this a regular event—the idea for the Paralympic movement was born.

The first Paralympic Games, held in 1960 after the Rome Summer Olympic Games, featured 400 athletes from 23 countries participating in 57 events in eight sports, and included only athletes with spinal cord injuries. Ray Werner competed in wheelchair basketball at these Games. At the 2018 Paralympics there were 80 medal events, and there are now ten different impairment types that athletes may have to be eligible to compete.

Werner’s championship basketball jacket, the number he put on the back of his wheelchair and the scrapbook containing that memorable letter are now part of the permanent sports collections at the American History Museum, where they represent the will of disabled athletes to carve out a place for themselves in the world of organized sports. Early on, Paralympic sports used traditional equipment and rules, allowing athletes to participate with little more than their wheelchair. As more programs and assistance for the disabled appeared, sports with more advanced ‘adaptive’ equipment began to emerge.

Another veteran who helped propel this new adaptive sports movement is Jim Martinson, a Vietnam soldier who lost both of his legs in a land mine explosion. An avid athlete before his injuries, Martinson began competing in wheelchair sports shortly after recovering—but it was his struggle on the ski slopes that turned him into an adaptive sports innovator. Mono skis were the only equipment available to disabled skiers at the time, but Martinson’s paralysis made it difficult to use a mono ski without help from others. Determined to ski on his own terms, he developed the ‘sit ski’ for greater independence.

This innovative piece of ski equipment allows the user to ride the chairlift without assistance, making the disabled skier more autonomous. Martinson went on to win a gold medal at the 1992 Winter Paralympics in Albertville, France, and in 2009, at 63, he became the oldest athlete to compete in the Mono Ski Cross at the Winter X Games. Unfortunately, Martinson didn’t save his early sit ski prototypes, but the American History Museum acquired a photograph of him in his sit ski invention for the collections. We’re now looking to acquire an actual sit ski sometime in the near future.

Chris Douglas, a Team USA Hockey member who won the gold medal at the 2015 IPC Sled Hockey World Championship, recently donated the hockey sled and sticks he used to earn his spot on that team. Born with spina bifida, a birth defect that left his spine underdeveloped, Douglas led a relatively active childhood until a corrective spinal cord surgery in March of 2001 left him paralyzed. As a result, his involvement with adaptive sports didn’t begin until 2011 at age 19. Adaptive athletes often become unexpected innovators and advocates for technological advancements. Douglas carved out a sled to fit his body, adjusting the frame and sticks to conform to his needs.

At 19, Amy Purdy suffered septic shock as a result of meningococcal meningitis. Due to loss of circulation, she had to have both legs amputated below the knee. Just two years later, Purdy competed in the United States of America Snowboard Association’s National Snowboarding Championship and medaled in three events. Her perseverance continued, and in 2005 she co-founded Adaptive Action Sports, a nonprofit organization which helps disabled athletes become involved in action sports. Purdy was the only double amputee to compete in the 2014 Paralympics Games in Sochi, where she won a bronze medal in snowboarding.

The sports history collections also now include the prosthetic sockets and feet used by Amy Purdy during her bronze medal run in Snowboard Cross, along with a Team USA uniform and a few awards she won along the way. Her prosthetics demonstrate the huge advancements made in recent years allowing athletes to perform specialized tasks with enhanced agility. New manufacturing techniques and computer imaging allow for better-fitted custom prostheses, which the athlete often helps design.

Mike Schultz is a perfect example of an athlete turned innovator and inventor. An extreme sports athlete and a 2018 member of Team USA, Mike was involved in a 2008 snowmobiling accident that fractured his knee and ultimately led to the amputation of his lower left leg, including his knee. Struggling to find his balance during races with his new prosthetic, Schultz realized he would have to develop his own prosthetic if he wanted to stay competitive in the extreme sports world.

The ‘Moto Knee’, serial number 002, was one of the first built by Mike Schultz’s company, BioDapt, Inc. in 2011. It uses an adjustable 250 psi mountain bike shock absorber to control the joint's stiffness with compressed air. From personal experience, Schultz knew that extreme sports athletes also required toe pressure and ankle tension. He went on to create the ‘Versa Foot’, in 2012, a foot-ankle combination that also uses a pneumatic shock absorber to mimic joint resistance. Versa Foot won the Popular Science Invention Award of 2013.

Schultz donated each of these innovative prosthetics to the collections, where they help tell his story of athlete turned inventor. His company produces prostheses for other adaptive athletes as well as wounded warriors. Schultz continues to compete as a three-sport X Games athlete, and currently holds the most adaptive gold medals in X Games history. Schultz won the gold in Snowboard Cross at the 2017 U.S. Paralympics National Snowboarding Championships. At the 2018 Paralympics in Pyeongchang, Schultz earned a gold medal in Snowboard Cross and a silver medal in Banked Slalom.

The American History Museum’s adaptive sport and Paralympic collections are steadily growing, and include equipment and prosthetics from many different sports, from athletes of many different abilities. As you watch the Olympics and Paralympics this year, keep an eye out for athletes who make a difference both on and off the field of play. Sports History staff are eager to collect more objects tied to Paralympians and their achievements, and bring these athletes’ stories to a national audience in hopes that scholars, researchers, athletes and fans alike will come to appreciate the histories of these exceptional champions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jane_Rogers.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jane_Rogers.jpg)