Until Now, There Was No Play Button for the Recordings Bell and Edison Made in their Lab

An exhibition on sound kicks off the American History Museum’s Year of Innovation, enabling visitors to hear some of the earliest recordings

It’s fitting that the National Museum of American History kicks off its "Year of Innovation" with an exhibition dedicated to one of the fiercest invention battles of the 19th century.

It was 1880; four years after Alexander Graham Bell had—to much fanfare—developed and launched the telephone. Since its release, the inventor had to respond to more than 600 patent challenges. So Bell would become extremely secretive, carefully protecting the information surrounding any potential new projects. His work now turned to not only the transmission of sound, but also significantly, to recording it.

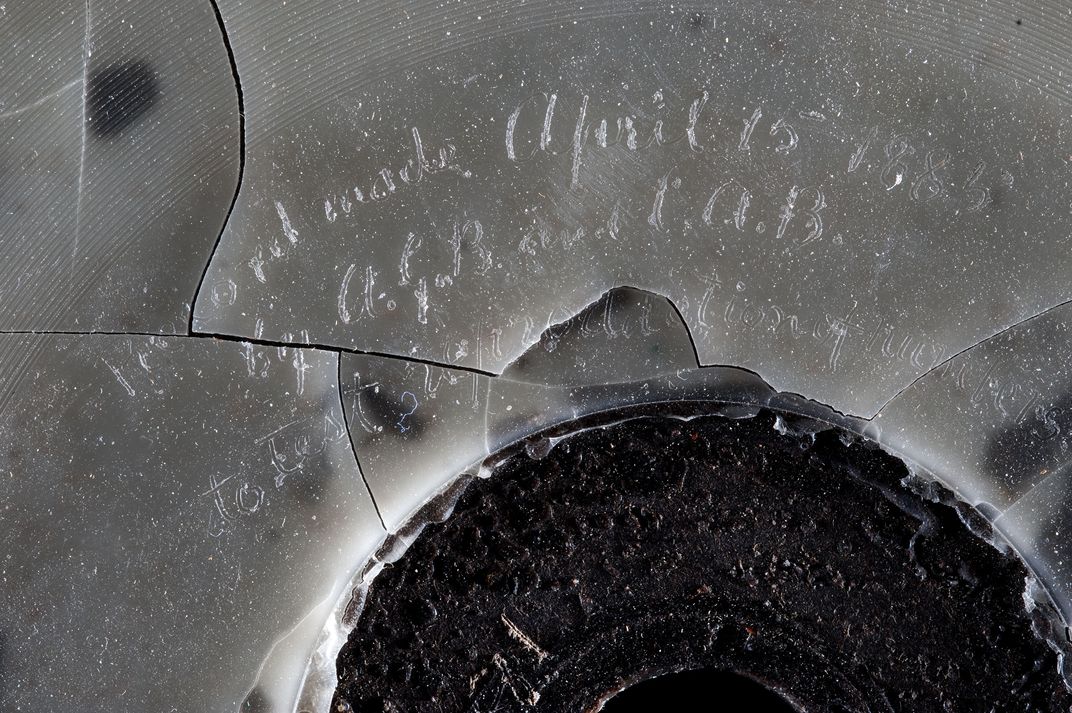

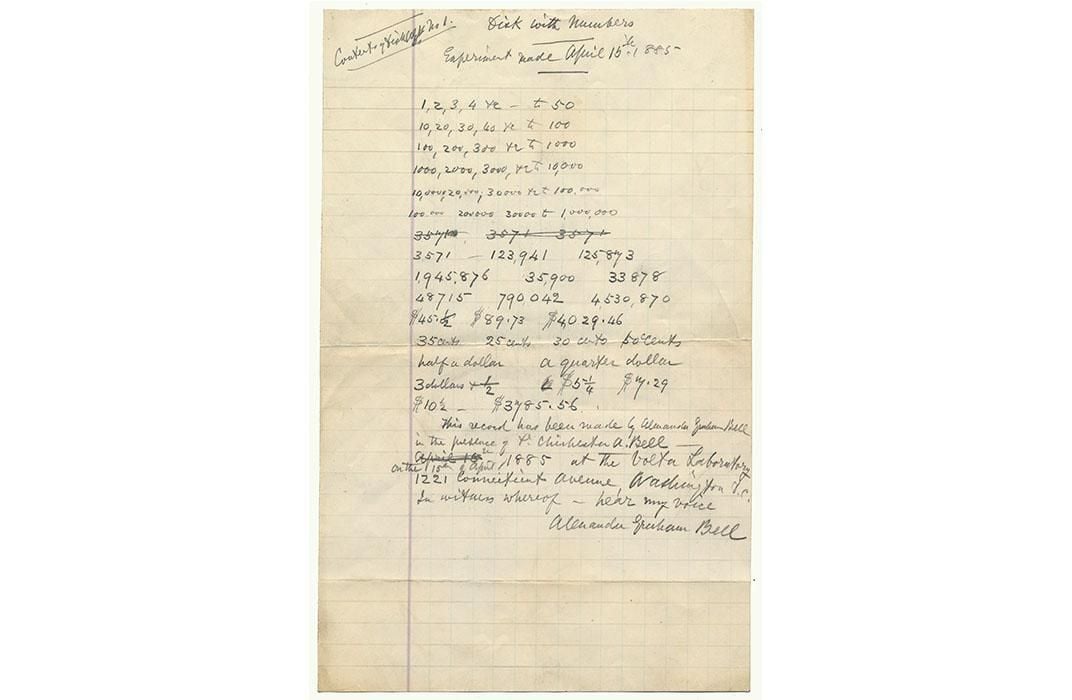

That year and the next, the cautious inventor deposited three sealed aluminum boxes into a safe that was located outside the Secretary’s office at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He said it was for safekeeping, but he also wanted to prepare a careful record in case he needed to show evidence that this was his work, so nothing could be called into question.

His concern was not unwarranted. His rival Thomas Edison was competing neck-in-neck. In 1878, Edison had demonstrated the phonograph at the Smithsonian, showing that his new device could record spoken voices on tinfoil-covered cylinders.

Bell’s boxes were never retrieved or opened until 1937. In addition to these boxes, which contained early prototypes of sound-capturing machines, he also donated hundreds of records and documents to the Institution. In 2012, one such record was ultimately played using breakthrough digital technology, revealing a sound recording that Alexander Graham Bell had successfully made of his own voice in 1885. Museum specialists and scientists later captured another 1881 recording of his father making the silly statement: “I am a graphophone and my mother was a phonograph.”

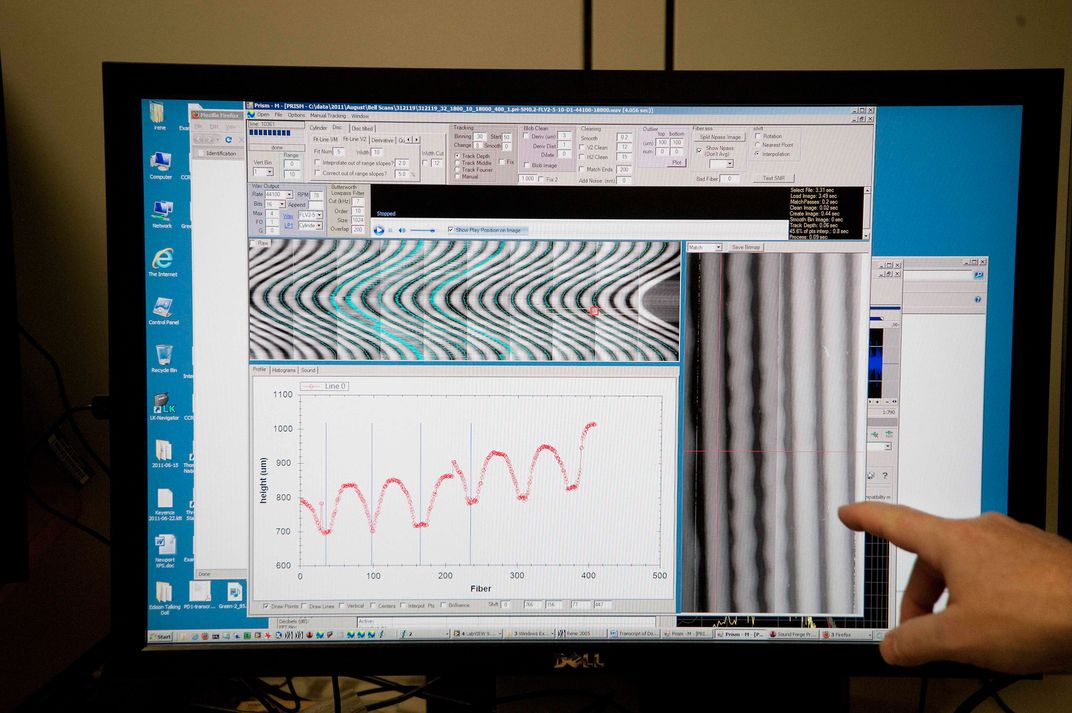

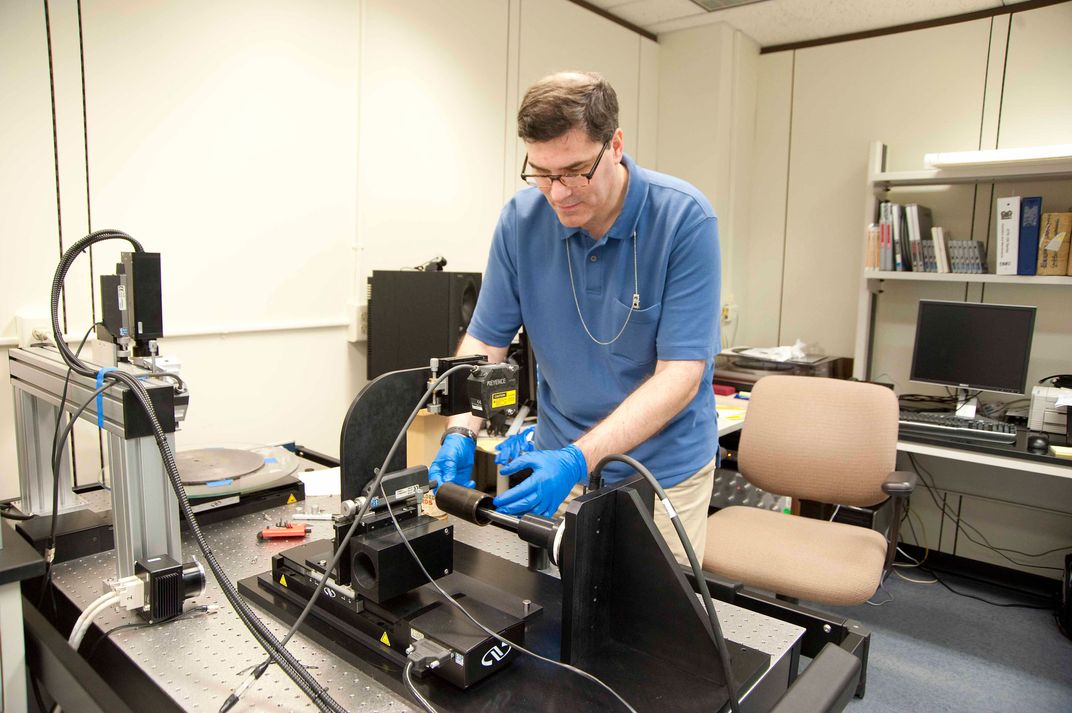

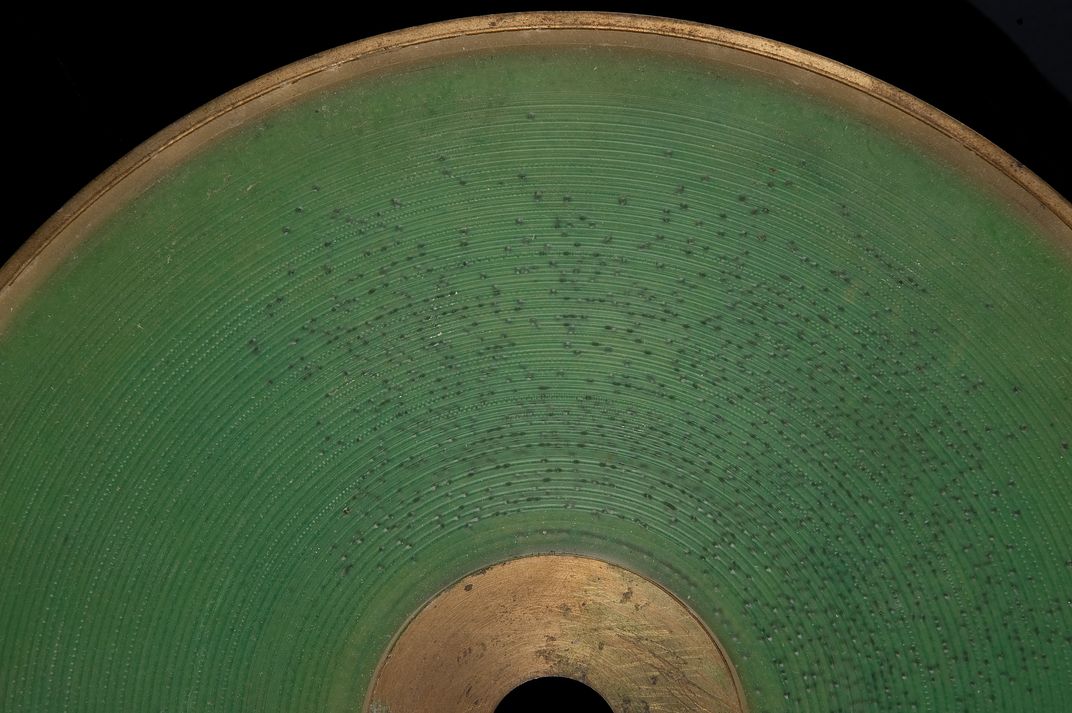

“This is like Apple vs. Microsoft and the battle of formats,” says Carlene Stephens, curator of the exhibition, “this was the leading edge technology of the 1880s.” The Smithsonian, in partnership with Carl Haber and Earl Cornell, scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, have managed to decode the sound from eight different records of that time, comprised of varying mediums including glass, green wax and aluminum foil.

In the new exhibit, “'Hear My Voice:’ Alexander Graham Bell and the Origins of Recorded Sound,” visitors will be able to listen to each of these recordings, which include everything from a man saying simply “barometer,” to instrumentals of the popular tunes of the day “Killarney,” and “Hot-Shot March.” They can also explore historical devices used to create these records, as well as touch 3D printed models of the actual grooves that the sound waves made on each material look and feel like.

“Every time they use the instrument on an old record, it’s an experiment,” says Stephens, “There is no typical way of doing it.” She emphasizes the importance of these discoveries in creating the earliest “museum of voices” and providing a new way of documenting history.

As Bell says in one of his featured sound clips, “This record was made.”

"'Hear My Voice:'" Alexander Graham Bell and the Origins of Recorded Sound" is on view at the National Museum of American History through October 25, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)