Using Art to Talk About the Holocaust in ‘The Evidence Room’

Museum staff discuss the reception of a difficult work that showed the vivid and painful documentation of a Nazi death camp

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/c1/b4c1f909-45f1-4e6a-be4d-f87864649bd2/104a0389_1.jpg)

In 1996 David Irving, a British writer known in certain circles for his expertise on Nazi Germany, sued Deborah Lipstadt, a historian and professor at Emory University, for libel because she called him “one of the most dangerous spokespersons for Holocaust denial.” Irving—who has asserted unequivocally and wrongly that ''there were never any gas chambers at Auschwitz”—strategically filed the lawsuit in the U.K. By law, the burden of proof for libel cases in that country lies with the defendant, meaning he knew that Lipstadt would have to prove he had knowingly promoted a conspiracy theory.

Lipstadt didn’t back down. A lengthy court battle ensued, and four years later, the British High Court of Justice ruled in her favor.

What the trial (later dramatized in the film Denial starring Rachel Weisz) ultimately came down to was a trove of irrefutable documentary evidence, including letters, orders, blueprints and building contractor documents that proved without a doubt the methodological planning, building and operating of the death camp at Auschwitz.

This past summer, The Evidence Room, an installation of 65 plaster casts that manifests a physical, sculptural representation of that trial, came to the United States for the first time, and went on view in the nation’s capital. Those familiar with Washington, D.C., might assume the exhibition was installed at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Instead, it went on view just a short walk down the street at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, where crowds jostled to see it on its short June to September showing.

“It really opens it up in a whole different way,” says Betsy Johnson, an assistant curator at the Hirshhorn. “You had people coming to see it here in the context of an art museum, who are very different than your populations at a history museum, or at a Holocaust museum.”

The Evidence Room was originally created as a piece of forensic architecture for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. Working through 1,000 pages of testimony, Robert Jan van Pelt, an architectural historian and the main expert witness for Lipstadt’s case, and a team from the University of Waterloo School of Architecture led by Donald McKay and Anne Bordeleau with architecture and design curator Sascha Hastings teased out the concept of The Evidence Room from the pieces of court evidence themselves.

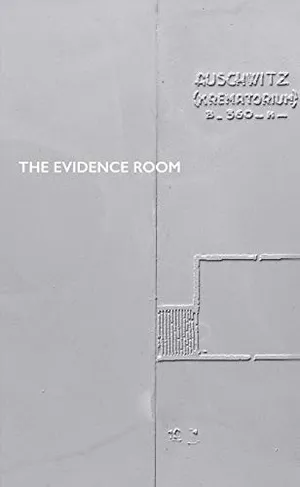

Everything in the work is unrelentingly white. Three life-size “monuments” are featured. They include a gas chamber door showing that its hinges had been moved because it was determined that if the door opened outward, more bodies could be put in the room. (The door was originally designed to swung inward, but it couldn’t open if too many of the dead were pressed against it.) There’s an early model gas hatch, which is how the SS guards introduced the cyanide-based Zyklon-B poison into the gas chamber. A gas column, which made the killings as efficient as possible, is also depicted. Plaster casts of archival drawings, photographs, blueprints and documents on Nazi letterheads populate the room as well. They are given a three-dimensional aspect thanks to a laser engraving technique and testify to how workers during World War II—carpenters, cement manufacturers, electricians, architects and the like—assisted in creating the most efficient Nazi killing machine possible.

Strong reception to The Evidence Room helped the architects to raise funds to return the work to Waterloo. From there, it was shown at Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, which is where Johnson first experienced it when she was sent there about a year ago by the Hirshhorn’s director and chief curator.

“I went there, and realized almost immediately that even though it hadn't been displayed in an art context before” says Johnson, “that it had potential for fitting into an art context.” Johnson recognized in the work connections with the direction that contemporary art has gone in the past four or five decades, a trend that places more importance on the idea behind the art object itself. "Really when it came down to it, even though it’s not a traditional art project, it fits so well within the trends that have been happening in the realm of contemporary art from the 1960s on,” she says.

But bringing it to the Hirshhorn meant considering the piece differently than how it had been framed before. “We realized fairly early on that there were certain ways that [Royal Ontario Museum] had framed the story that were different than the ways we did,” she says. “Things like the materiality of the work, which while they did discuss this at the Royal Ontario Museum became even more the focus in our museum,” she says. “The plaster was one that was actually quite symbolic for [the creators],” she says. “They were thinking it through on multiple different levels.”

Because this wasn’t a history museum, they also decided to go more minimalist with the text. “We still wanted people to be able to access the information about it,” says Johnson. “But we also wanted them to have this experience of confronting an object that that they don't quite understand at first.”

Asking the audience to do the work to engage with what they were seeing on their own, she felt, was key. “That work is really important work,” Johnson says. “Especially within the space of this exhibition. We felt like there's something kind of sacred about [it]. We didn't want people to be mediating the space through their phones or through a map that they hold in their hand.” Instead, they relied more on the gallery guides like Nancy Hirshbein to supplement the experience.

Hirshbein says the most frequent question from visitors was: “Why is it all white?”

“That was the number one question,” she says. “Visitors would stop. As soon as they walked in, you can tell that they were struck by the space. And I would approach them and ask if they had any questions. And then I would often prompt and say: ‘If you're wondering about anything, if you're wondering about why the room may be all white, please let me know.’”

That opened up the conversation to discuss the materiality of the white plaster, and what it may have meant to the architects who designed the room.

“I would also like to find out from the visitors their interpretation,” says Hirshbein. “We sometimes did some free association, about how it felt to them to be in this very minimal white space.”

By design, the all-white nature of the panels made them difficult to read. So, visitors often needed to spend time squinting or navigating their own body in order to better read the text or see the image. “Sometimes,” says Hirshbein, “visitors intuited that. They would say things like: ‘Oh, this is difficult to read,’ and then look at me and go: ‘Oh, because it's difficult material.’”

That’s just one thing that could be pulled from that. “We're also looking through a backward lens of history,” as Hirshbein says, “and the further we get away from these things, the more difficult they are to see. That's the nature of history.”

Alan Ginsberg, who serves as the director of the Evidence Room Foundation, the custodian of the work, mentions during our conversation that for him, he notices in different light, coming from different angles, that the shadows the plaster casts stand out. “It allows history to be recovered,” he says. “It allows memory to be recovered.” What you're left to do, as the viewer then, “is to understand and try to grapple with what is absent from there.”

The Evidence Room

Internationally renowned and award-winning historian Dr. Robert Jan van Pelt's The Evidence Room is a chilling exploration of the role architecture played in constructing Auschwitz—arguably the Nazis' most horrifying facility. The Evidence Room is both a companion piece to, and an elaboration of, an exhibit at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, based on van Pelt's authoritative testimony against Holocaust denial in a 2000 libel suit argued before the Royal Courts of Justice in London.

Ginsberg says the Evidence Room Foundation, which partnered with the Hirshhorn on the exhibition, was fully on board with how the Hirshhorn framed the work. “The Hirshhorn was the obvious and perfect and premier place for this debut not only in the United States, but in the world of art,” he says. Like many people, he sees the room embodying many identities, including being a work of contemporary art.

Holocaust art has always been a controversial topic, something that Ginsberg is very aware of when he talks about the room as art. “Can you represent the Holocaust through art without being obscene?” he asks. “This is a question that has been debated endlessly. And I think the answer clearly comes down to—it depends on the specific work. There are works of art that are understood to be commemorative, or educational, or evocative, in a way that is respectful. And that's what The Evidence Room is.”

Still, he says, there's something in the work and the way it’s crafted that does give him pause. “Is it wrong to have something that refers back to atrocities and yet the representation has a certain eerie beauty to it? These are good questions to ask,” he says. “And they're not meant to be resolved. Ultimately, they're meant to create that artistic tension that provokes conversation and awareness.”

The Evidence Room Foundation, which only launched just this year, is looking to use the work as a teaching tool and a conversation starter. Currently, Ginsberg says, they’re speaking with art museums, history museums, university campuses and other kinds of institutions, and fielding inquiries and requests about where to exhibit The Evidence Room in the future. For now, he’ll only say, “Our hope is that we will get a new venue announced and put in place before the year ends.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.