Muslim fashion is big business. Statistics from a 2016-2017 report by Thomson Reuters and DinarStandard, a global strategy firm that focuses on the Muslim market reports that Muslim women spent $44 billion on fashion that year, which represented 18 percent of the total estimated $243 billion spent by all Muslims on all clothing. By 2024, DinarStandard estimates, Muslim consumers will spend $402 billion.

Before it closes on July 11, try to catch “Contemporary Muslim Fashions,” an exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. Not only are there dozens of gorgeous shimmery brocade, silk and satin gowns from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Middle East and Europe, but also hip hop-inspired contemporary sportswear, videos of interviews with young women Muslim designers (half under the age of 40) and fashion videos. There are examples of haute couture that Westerners like Karl Lagerfeld, Valentino and Oscar de la Renta adapted for their Middle Eastern clients, and affordable dresses sold at Macy’s and Uniqlo. The show is the last stop on a tour that began in San Francisco and then moved to Frankfurt. And sadly, though the museum just reopened June 10, the show is only on view for just a month at its final New York City stop.

Contemporary Muslim Fashions

This dazzling exploration of contemporary Muslim modest dress, from historic styles to present-day examples, accompanies a major exhibition and reveals the enormous range of self-expression through fashion achieved by Muslim men and women.

It is an important show. “Contemporary Muslim Fashions” is the first major museum exhibition to focus on contemporary Muslim dress around the world—and it’s long overdue.

The origin of the show was kismet.

“It was one of the things I had in mind before coming to San Francisco in 2016,” says Max Hollein, the Austrian curator who became director of the de Young/Legion of Honor Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco that year, where the show originated. (Hollein is now director of the Met.) “It was the first time I was at an institution with a textiles collection, and because I had gone to Tehran a lot as director of the Sta[umlaut]del Museum in Frankfurt and spent considerable time in Istanbul and seen very fashionable women there, I got interested in Muslim dress codes.” (His wife, the Austrian architect Nina Hollein, is a fashion designer who founded her own label, NinaHollein, in 2009.)

The de Young didn’t have any Muslim curators, but at Hollein’s very first meeting with Jill D’Alessandro, the museum’s curator of costume and textile arts, he discussed the disconnect between the Western perception of Middle Eastern fashion and reality.

“There are those who believe there is no fashion among Muslim women, but the opposite is true, with modern, vibrant and extraordinary modest fashion scenes established around the globe, particularly in many Muslim-majority countries,” he writes in the show catalog.

D’Alessandro, realizing that nearly 250,000 Muslims live in the six counties surrounding San Francisco, embraced the idea. She formed a team with Laura L. Camerlengo, associate curator of costume and textile arts at the de Young, and Reina Lewis, a professor of cultural studies at the London College of Fashion and the University of the Arts London, who is considered a top scholar on Muslim fashion.

“We put feelers out, and I followed the news cycle very closely,” D’Alessandro says. “We studied Vogue Arabia and Harper’s Bazaar Arabia. We followed word of mouth, fashion bloggers, Instagram. We lived it 24/ 7.” She investigated the history of Modest Fashion Week, days of Muslim-oriented fashion shows that follow the regular shows in Dubai, Istanbul, Jakarta and, in 2017, New York. She surveyed the many e-commerce sites like The Modist, which launched in 2017 with 75 Muslim designers (it closed during the pandemic).

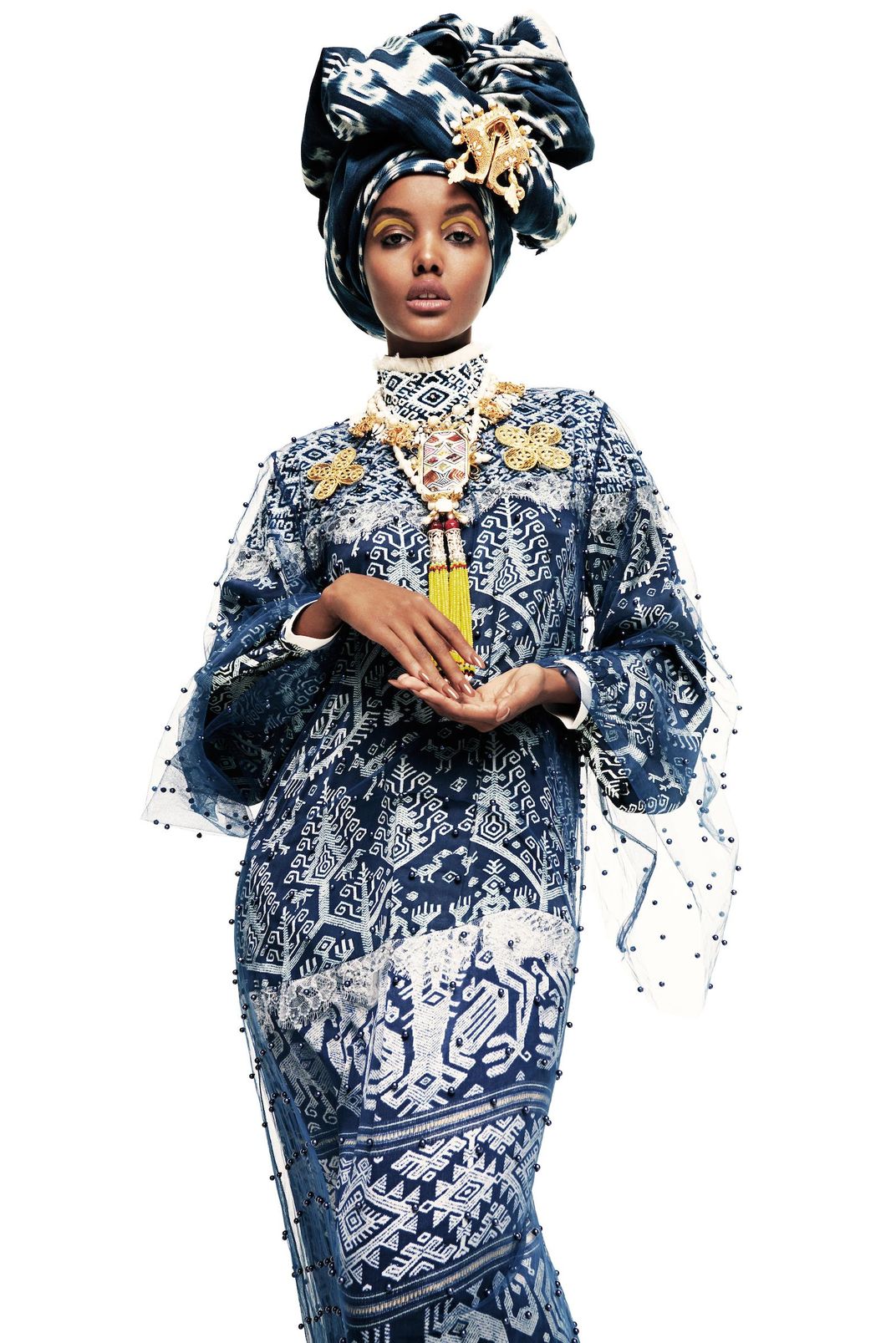

“We decided to spotlight the regions that have captured the moment,” D’Alessandro says. “We wanted to show enough diversity to show that this is a global phenomenon.” The exhibition is organized geographically, with sections on Indonesia (which has the largest Muslim population in the world, about 207 million), Malaysia (with 61 percent of its 32 million population Muslim), the Middle East, Europe and America.

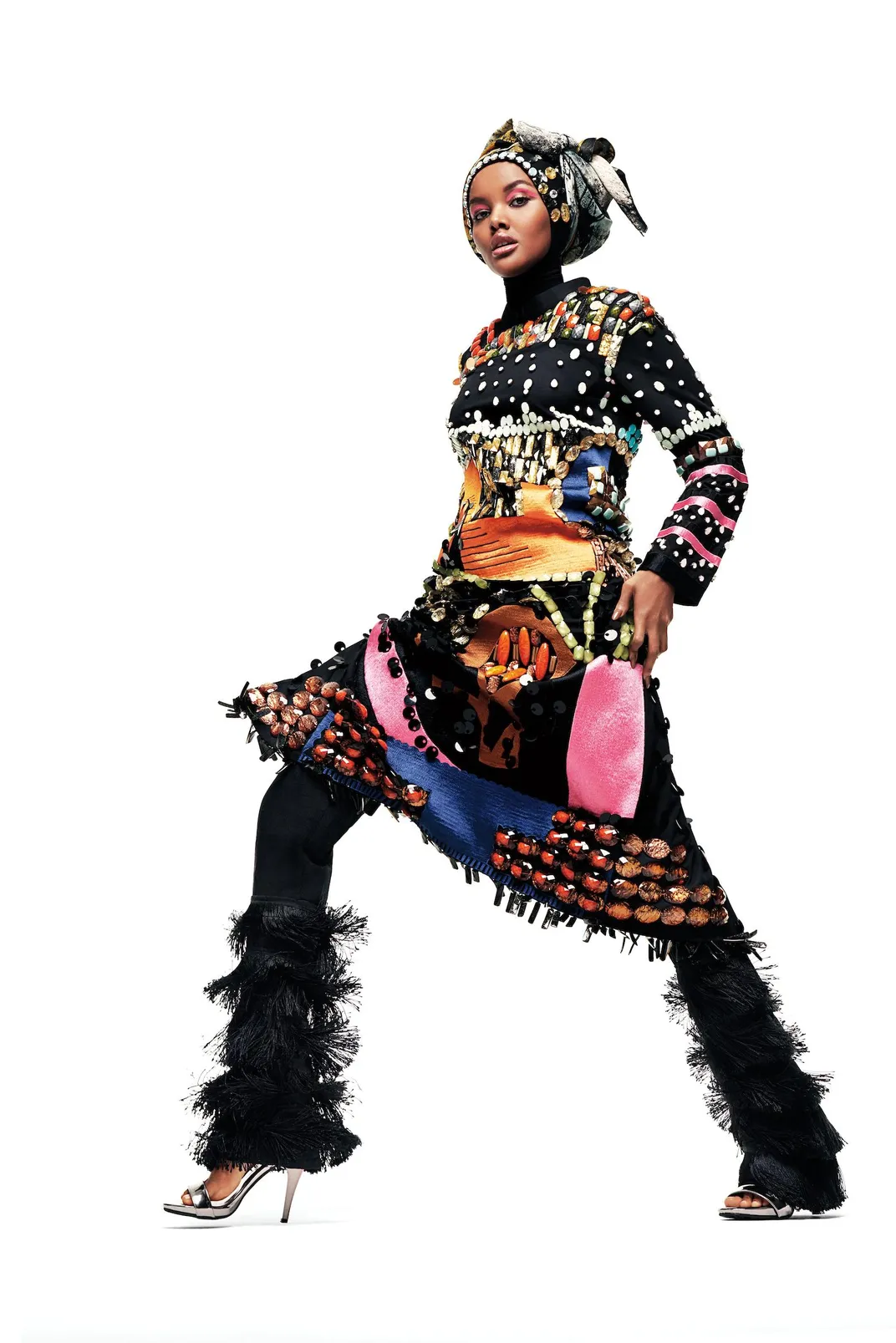

It is all about so-called Modest Fashion, that is, outfits designed to cover the body in keeping with Islamic principles. (Of course, Modest Fashion appeals to women of all faiths and cultural backgrounds.) Many mannequins wear updated versions of the abaya, a traditional cloak that covers the body to below the ankles, with sleeves extending to the wrists. Half of them wear the hijab, the religious veil worn by Muslim women that covers the hair, head and chest (but not the face) when they go out in public.

The hijab can mean different things. Many women wear it to demonstrate their submission to God and their modesty. Others wear it to signal they are proud to show off their faith and ethnic identity.

“There is a high degree of diversity concerning head coverings among regions and generations,” explains Susan Brown, the Cooper Hewitt curator involved with the show.

It even includes Modest sportswear.

“In 2017 Nike became the first global sports brand to enter into the Modest sportswear market with the release of the Pro Hijab,” Brown continues, pointing to a wall-size photo of the Olympic medalist fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad in hers (the Nike Pro Hijab is a Smithsonian-owned item in the show, which is comprised of loans from designers and private lenders).

Demand for modest but stylish clothing turns out to be huge, especially on the internet.

One major online retailer represented is Modanisa.com, which collaborates with Rabia Zargarpur, a Washington, D.C.-based designer originally from Dubai who founded Rabia Z in 2002, one of the older ready-to-wear companies selling modest fashion. She is particularly famous for her licensed hijab line, which she claims is the best-selling hijab in the world. She founded the Modest Fashion Academy to mentor the next generation of designers. “We need modest ready-to-wear,” she says. “Our clothes are about comfort, timelessness, sisterhood and sustainability. We invented an organic cotton jersey hijab because the old hijabs didn’t breathe. Now we are selling to 72 countries.”

YouTube and Instagram play a huge role in Muslim fashion, for designers, bloggers and influencers. (The Indonesian designer Dian Pelangi, who participated in New York Fashion Week in 2017 and is featured in the show, has nearly five million followers, for example.)

There are 1.8 billion practitioners of Islam worldwide, comprising 24 percent of the global population. As this show proves, Muslim women will not be ignored on the fashion front.

“Contemporary Muslim Fashions” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City through July 11, 2021. Free tickets must be reserved in advance.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/bb/f8bb733a-10fc-45fb-8dc4-034a15fb98e7/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/d0/90d0256c-00da-436b-9ff3-95f85eeda9d7/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)