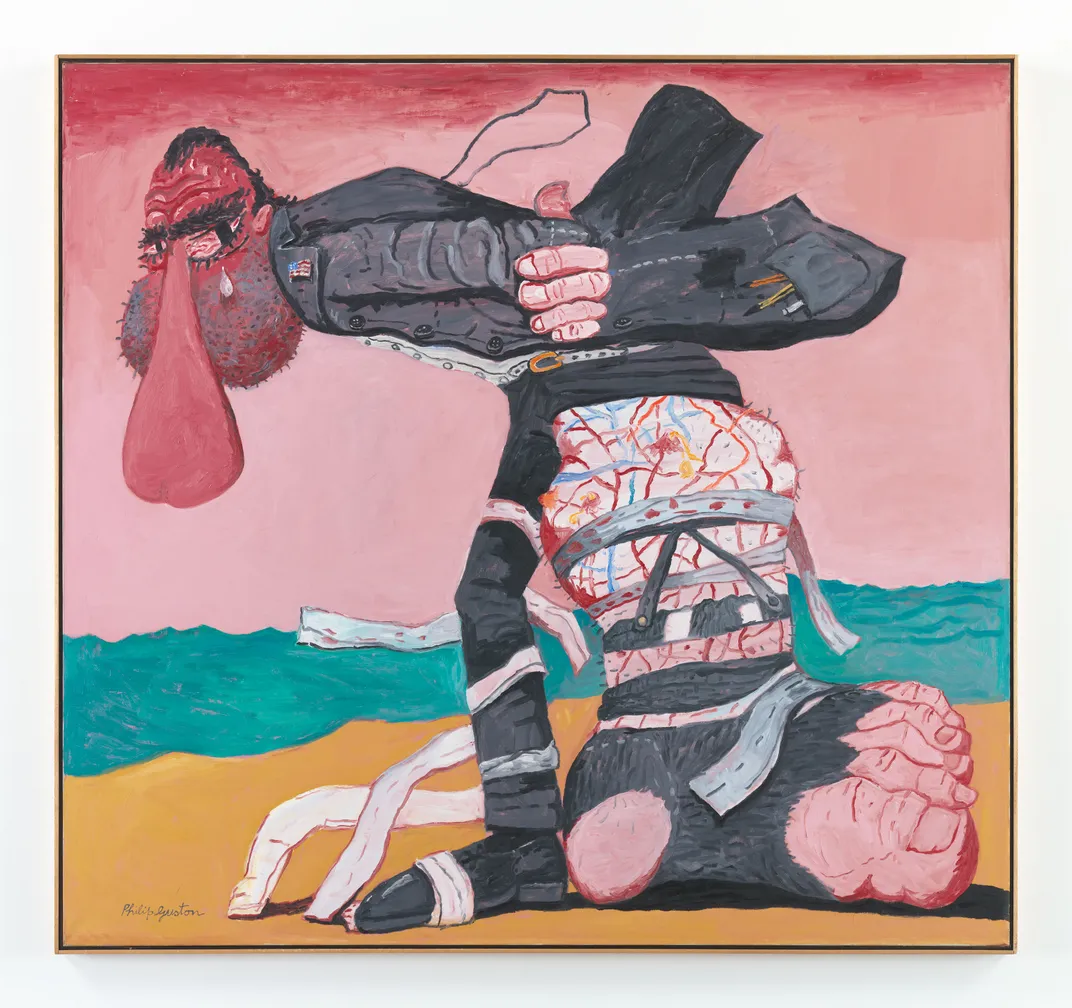

In 1965, as the Vietnam War escalated overseas amid civil unrest at home, abstract artists as accomplished as Philip Guston wondered whether they were doing the right thing. “What kind of man am I,” he wondered, “sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

Vietnam pushed him into a more direct commentary on the world—and a sudden shift toward representational, though often cartoonish, satirical attacks on hate groups and elected officials.

One of them, San Clemente, a vivid painting targeting Richard Nixon in 1975, is part of a major survey titled “Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-1975” and now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The show brings together 115 objects by 58 artists working in the decade between Lyndon Johnson’s decision to deploy U.S. ground troops to South Vietnam in 1965 and the fall of Saigon ten years later.

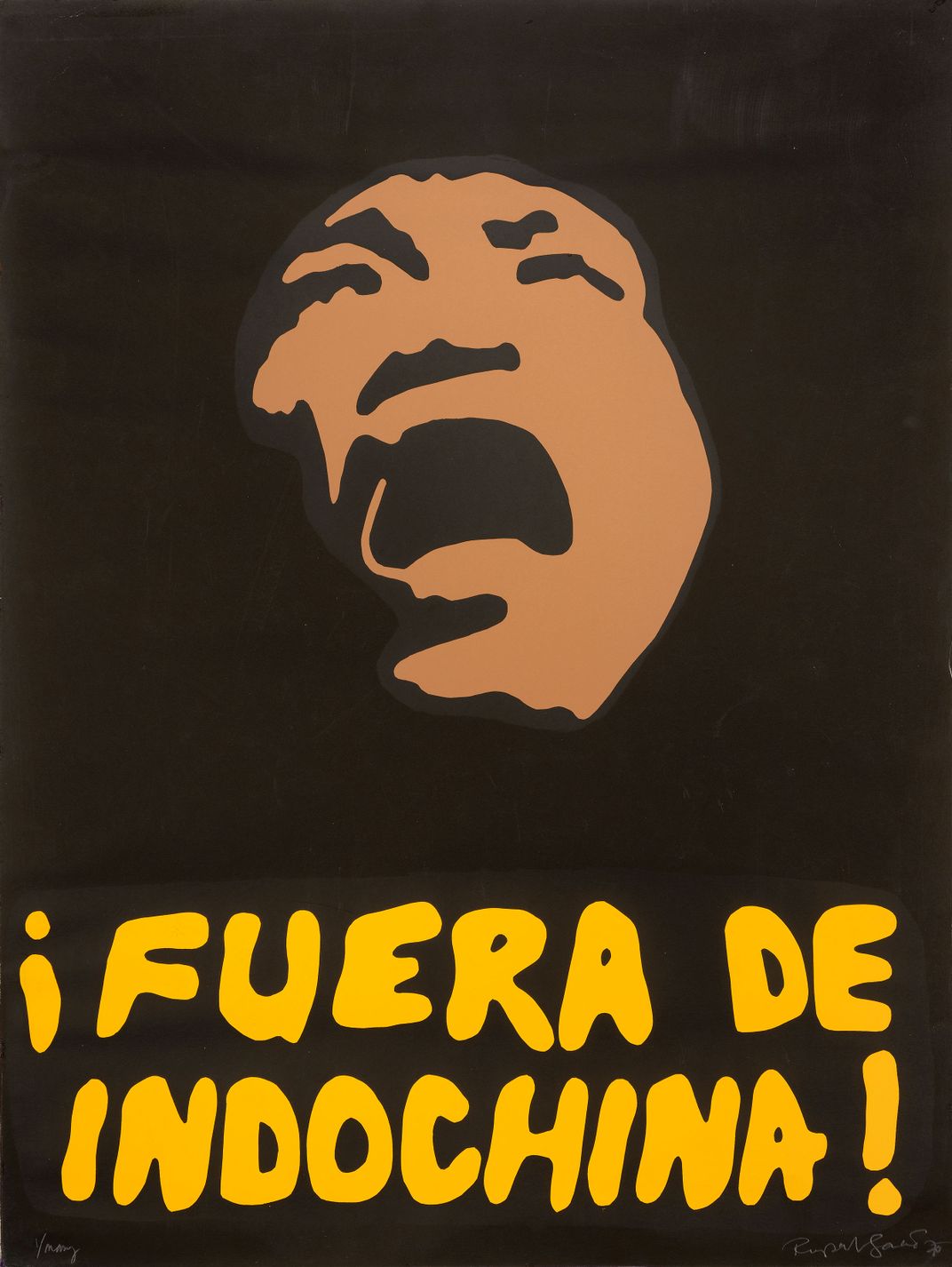

With devastating loss of life—nearly 60,000 U.S. casualties and an estimated three million soldier and civilian losses in Vietnam—the war produced some of the most significant ruptures in social and political life across the country and stoked a divisiveness that is still being felt today. Just as it changed America, the war changed art itself, shaking artists into activism and often into creating works quite different from any they had done before. The exhibition, organized by Melissa Ho, the museum’s curator of 20th-century art, is chock full of such examples.

Ad Reinhardt took a break from pure abstraction to create a screenprint of an airmail postcard addressed to the “War Chief, Washington, D.C. USA” demanding “No War, No Imperialism, No Murder, No Bombing, No Escalation…” and so forth, as part of the portfolio Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam.

Barnett Newman stepped away from his own abstract paintings to create the stark barbed-wire sculpture Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley following the bloody 1968 Chicago riots there during the Democratic National Convention, spurred in part by the war in Vietnam.

Claes Oldenburg’s own post-Chicago response was a pair of fireplugs he suggested people throw through windows (the pop artist is also represented in the show by documentation of a military-like lipstick commissioned by students at Yale).

Donald Judd turned away from his metal boxes to create a broadside with typewritten quotes about war from Jefferson and De Tocqueville to Frederick Douglass, Emerson, Thoreau to Dean Rusk and Robert LaFollette.

Yayoi Kusama may be celebrated these days for dots, pumpkins and mirrored infinity rooms, but in 1968, she was taking her own stance against the war in performance pieces involving naked people cavorting at power centers, captured in photographs documenting her Anatomic Explosion on Wall Street.

There is a box to walk into (with timed entrances) in the Artists Respond exhibit, but it is Wally Hedrick’s War Room, in which the darkness of the era is literally enveloping.

Some artists addressed the war in their established medium. Earthwork artist Robert Smithson poured dirt on a structure until it could take no more to get his point across in Partially Buried Woodshed, Kent State, an action captured in a 1970 photograph.

Dan Flavin continued to work in his fluorescent tubes to create his war statement, the red-tinged monument 4 those who have been killed in ambush (to P.K. who reminded me about death), while Bruce Nauman’s 1970 neon Raw War spelled out the conflict, front and back.

Artists who fought in Vietnam also changed their approach forever, perhaps none more than Jesse Treviño, a Mexican-born Texan and Art Students League scholarship winner, who went to Vietnam when drafted in 1967 and suffered a severe injury while on patrol in his first months that caused his right hand—his painting hand—to be amputated.

Upon his discharge, he had to learn his craft with his left hand, in the darkness of his bedroom where he painted the monumental Mi Vida on the wall, depicting the swirling elements of his life, from his prosthetic arm, to his Purple Heart medal, the Mustang he bought with his compensation, and the things that helped get him through, from coffee and cigarettes to Budweiser and pills.

“Being wounded in Vietnam was the most horrific thing that could happen to me because my painting hand was my right hand,” says Treviño, who at 72 attended the opening events. “When I came back from Vietnam I didn’t know what I was going to do.” He managed to change the hand he used in painting and his approach, as he’s become a renown muralist of Chicano life in San Antonio. Mi Vida was his first attempt with the new approach. “The painting you see was done on a Sheetrock,” he says. “I never imagined that it could even be extracted from the house.”

Treviño wasn’t the only artist on hand to share art from half a century ago. Also present was Peter Saul, whose kaleidoscopic scenes in cartoonish swirls and day-glo colors, depicted war horrors, such as those suggested in the words “White Boys Torturing and Raping the People of Saigon - High Class Version” displayed at the bottom corner on his 1967 Saigon. The mayhem continues in his 1968 Target Practice. “I tried to go too far whenever I could,” says Saul, 84. “Because I realized that the idea of modern art is: If you don’t go too far, you haven’t gone far enough.”

It also suits the subject matter, says Judith Bernstein, whose 1967 A Soldier’s Christmas was even more in-your-face with twinkly lights, Brillo pads, a woman spreading her legs and the kind of antiwar slogan that might be found on the walls of a bathroom stall. “The aesthetic is very crude,” says Bernstein, 76. “But I’ll tell you something, you can’t be as crude as the killing and the maiming and all the things that happened in destroying the country that we did in Vietnam. I felt that whatever you do, it can’t be as horrible as the war itself.”

It’s all about “artists on the home front, responding to events as they are still open ended and unresolved,” says the curator Melissa Ho. It was a time of both “unparalleled media coverage” and with a wide variety of artistic approaches flourishing.

“At the time,” she adds, “in the early 60s, socially engaged art had fallen out of fashion among modern artists in this country.” But the upheavals in the country, led by debate on the war, “demanded new thinking about what form art could take, what aims art should have and it prompted a new flourishing of artistic expression.”

Ho quotes the artist Leon Golub, whose Vietnam II, at more than 9-feet tall and nearly 38-feet long is the largest work in the show, as saying, “Paintings don’t change wars, they show feelings about wars.”

“More than anything else,” Ho says, “this exhibition shows us some of what the country was feeling about the war.” It makes for a monumental show that is paired with a contemporary artist’s own exploration into her personal history and the lives of Vietnamese-Americans since the war, Tiffany Chung: Vietnam, Past is Prologue.

“We are really inserting a chapter in American art history,” says the museum’s director Stephanie Stebich, who says “Artists Respond” is “for the first time grappling with how the Vietnam War forever changed American art.”

For Treviño, the wounded war veteran whose Mi Vida gets prized placement at the end of the show, “I never realized this particular painting was going to be part of a very important exhibit,” he says. “My dream was one day to be in the Smithsonian.”

“Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1865-1975,” curated by Melissa Ho, continues through August 18, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. It will be exhibited at the Minneapolis Institute of Art September 28, 2019 to January 5, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/82/00826afb-ff12-4748-9c91-f9d0aaabf706/trevino_mi-vida.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)