Vietnam War Vets Reconnect With Their 1960s Pen Pals For a Museum Donation

Decades after they sat in Mrs. Davis’ fourth grade class, former students donated Vietnam War materials to the American History Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/29/7c29659f-9b9e-4073-9171-43f638595843/letters.jpg)

Like many school groups last Friday, Mrs. Jerry Davis’ fourth graders marched through the halls of the National Museum of American History. The group was from Camden, New Jersey, but their journey was more than just a school bus ride; Davis’ students are now in their late 50s and recently reconnected over items they had saved from a pen pal program that began during the Vietnam War. The teacher and former students donated the items to the Smithsonian on Friday, November 14.

It was 1967 when Davis told her 25 or so fourth graders at Yorkship Family School that for homework they would write to American soldiers in Vietnam. The project began with letters to someone Davis knew. “We had a friend whose son was homesick, so I had the kids write to him,” Davis said at the museum on Friday. “Then we got anybody that we knew or found out that was over there, we decided to write to them all.”

Not all parents were in favor of the project at first, but Davis convinced them of its importance. “They’d come in and talk to me about it. And I’d have to tell them, ‘This is not about the war that’s unpopular, this is about men that are over there, and they didn’t send themselves,’” she said.

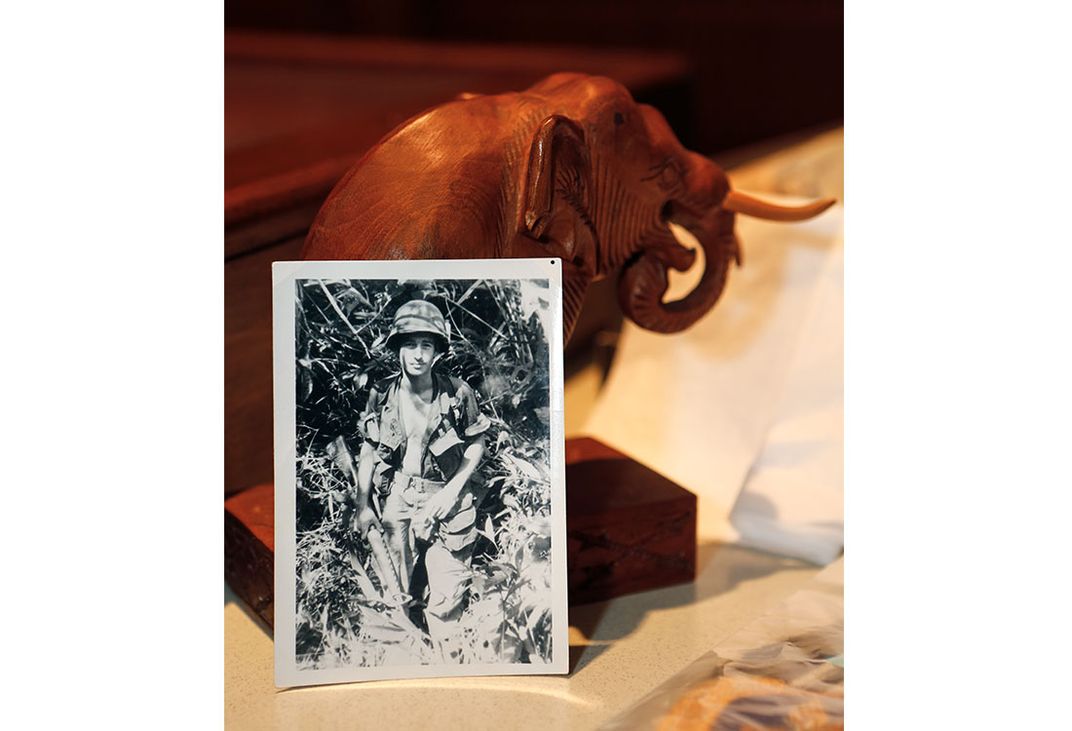

One of the soldiers who received letters was Joe Meskaitis, whom the kids called “Mosquito.” Meskaitis and two of his former student pen pals, Bill Harrison and Bruce Nelson, reunited at the museum last week. Meskaitis brought with him his two granddaughters, one of whom is the same age the students were when they wrote to him.

“He would tell you about the weather, he would tell us about what part of Vietnam he’s in. A lot of times he would say, ‘I’m writing this letter in the moonlight on the beach,’” Harrison said about Meskaitis. Harrison recalled writing about roller-skating and his love of the Jackson 5.

The correspondence went beyond letters. Kids sent their Halloween candy and Harrison had his grandmother bake chocolate chip cookies, which he described as getting “airdropped into the battle field.” Soldiers mailed back small figures, such as a wooden elephant and a bronze frog.

“We were just kind of careful what we wrote to make sure it was fourth grade level,” Meskaitis said. “We just left the horror stuff back there.”

As the letter writing continued, however, Davis found it impossible to keep the reality of war from her students. When one of the pen pals, Army Lt. Eugene Moppert, was killed in action, Davis decided to tell the class. “There was silence in the room and then some of the girls started to cry,” Harrison recalled. “She tried to explain the best she could what that meant and how he died over there.”

Recognizing the relationship between the fourth graders and Moppert, the lieutenant’s widow visited the school and donated the flag that had draped her husband’s coffin. For nearly half a century, the flag rested in a wood and glass case attached to a brick wall near the school’s auditorium. It had gone untouched, even as the walls around it got repainted. This past September, Davis and her former students asked the school if they could have the flag for a donation, and school officials said yes.

The pen pal project, which Davis assigned to classes over the course of four years, resonated with the students. One girl, Denise Knettle-Moloy, had a brother and brother-in-law serving in Vietnam at the time. “After writing and going to school and her talking about it, it was like a whole total different experience,” Knettle-Moloy said about her former teacher.

Kathie Gabriel, one of the eight former students at the museum last week, said she has stayed in touch with her pen pal, though now they correspond by Facebook message rather than handwritten letter. Another former student, Wendy Strang Rooney, said Davis inspired her not only to become a teacher, but also to have her own students write letters to troops.

Harrison is the one who contacted the American History Museum and coordinated the donation that includes letters, battalion pins, photographs and Moppert’s flag. Those artifacts will join the museum’s collection of Vietnam War materials, some of which are on display in The Price of Freedom, an ongoing exhibition. “It’s about the American public’s relationship with soldiers,” said curator Kathleen Golden about the donation. “When you come by something like this, it’s great.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)