The View From the Big Top

Aerialist and this year’s Folklife Festival performer Dolly Jacobs didn’t have to run away to join the circus; she lived it

:focal(565x234:566x235)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/c3/7cc3710e-337e-4582-8085-52b20132b6c6/dolly-jacobs-1.jpg)

According to aerialist Dolly Jacobs, creating a circus act is “like making a cake.” A single performance’s many ingredients—the acrobatics skills, the entrance, the costume, the music, the drama—all contribute to the spectacle. Jacobs knows this firsthand. The finale of her Roman rings act, her signature “flyaway somersault” from the rings toward a distant suspended rope, is nothing less than spectacular.

The act is expertly crafted to take spectators on a rollercoaster ride of fear and awe. Jacobs moves slowly with fluidity, concealing the magnitude of difficulty while simultaneously emphasizing its danger. Jacobs’ only sense of security comes from her setter, the person controlling her rope from the ground, who she trusts to deploy the rope just as she needs to catch it. The resulting act impresses circus novices and seasoned professionals alike, a masterpiece of circus craft steeped in techniques that have wowed audiences for decades.

Jacobs grew up in Sarasota, Florida, dubbed the “circus capital of the world” where in 1927 the Ringling Bros. established their winter quarters. She has spent her life surrounded by circus, including four years with Sailor Circus, a youth program she now runs with her husband and fellow aerialist Pedro Reis. Just like any other kid at the circus, she was enthralled, a little afraid, and very much in awe of the performers she idolized. She still treasures an autograph book she began compiling as a child, which is filled with the signatures of these now-immortalized performers.

One of her earliest inspirations was Dora “Rogana” Foster, a sword balancer. As part of her act, Foster balanced a tray of filled drinking glasses on the hilt of a sword, which was itself balanced on the point of a dagger that she held in her mouth. Foster maintained all of this while climbing up and down a swaying 40-foot ladder. Jacobs remembers being captivated by Foster's beauty, poise and elaborate costumes.

“I knew, in my heart of hearts, that I was going to be in the ring, and be as great as that woman,” she recalls.

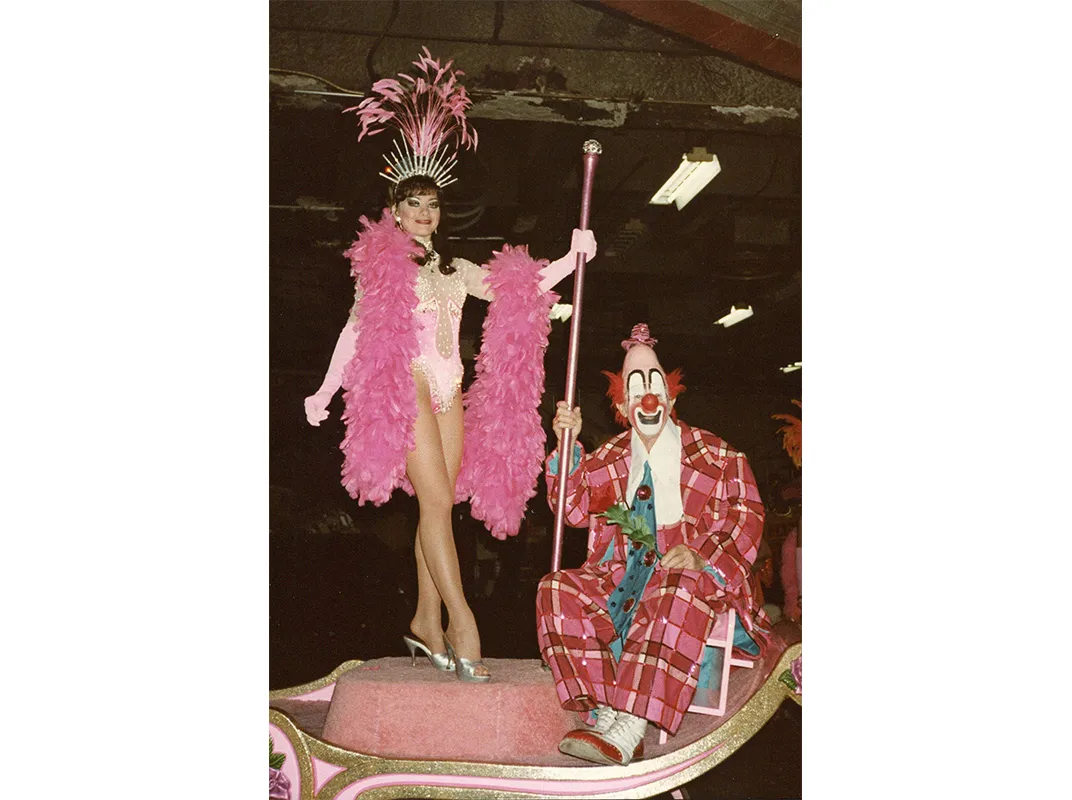

Though impressive performers abounded in Sarasota, Jacobs had no shortage of role models in her own family. Her father, Lou Jacobs, was a world renowned clown who performed with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus for more than 60 years. He is best remembered for his tiny clown car, into which he comically folded his tall stature. And for decades his iconic red-nose image represented Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey.

Her father was a great inspiration to her, and they enjoyed a very close relationship. When Lou Jacobs stepped into the tent to perform, she remembers that “he owned the ring.” They delighted in watching each other’s acts, beaming with pride from the sidelines.

Her mother, Jean Rockwell, was one of the top ten Conover models in New York before joining Ringling Bros. as a showgirl and dancer. Her godmother, Margie Geiger, was a ballet dancer from New York before joining the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus and married a member of the legendary Flying Wallendas. Geiger introduced Jacobs to the Roman rings apparatus and helped her develop her first solo act.

Regardless of her family’s history, she insists, “Nothing was given to me except inspiration, coaching and a wonderful upbringing.” The circus rewards hard work, she adamantly asserts.

At age 14, Jacobs joined the circus as a showgirl. She, her parents, and the other performers lived on a train, a long-standing Ringling tradition. She was homeschooled for four to five hours a day, all the while being exposed to countless American cities, towns and cultural landmarks that most children only read about. She had always been very shy, she remembers, but the circus encouraged her to interact with people from all over the world and eventually, she come out of her shell.

She and the other showgirls rode horses and elephants, danced, and performed aerial acts in groups. In their dressing rooms, her fellow performers taught her how to sew, knit, cook and mend costumes—skills they brought from their diverse backgrounds. Jacobs is fluent in Bulgarian and Spanish and speaks some Polish and German.

Bolstered by her experiences, she says she is instilled with an unwavering sense of self-confidence, which she works hard to help her students find today. “You can’t teach self-pride,” she says. “That’s something you have to earn.” And there’s no better place to earn it than the circus.

Jacobs emphasizes, above all else, immense gratitude for the performers who have come before her. The circus arts, like any form of folk art, are sets of skills passed down through generations. She acknowledges that her predecessors opened the gateway to a multitude of circus and performance knowledge, passing on techniques they were taught by the previous generation.

In September 2015, when she accepted the NEA National Heritage Fellowship—the first circus artist to do so—she insisted, “This is not for me. It’s for them.” Without a doubt, when Jacobs’s students achieve incredible feats in their own careers, they will acknowledge her with the same reverence.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/d6/2ad6b1eb-72ae-4c76-b4a0-de19e426e209/dolly-jacobs-sailor-circus-wr.jpg)