Viewing Iran and Its Complexities Through the Eyes of Visual Artists

Compelling works from six female photographers tell stories of revolution, displacement and longing for home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/83/0283e28a-9de2-4005-9a31-6758ccbde24f/hengameh_s201519crop.jpg)

The snowflakes, the ones unimpeded by the decorative umbrellas, fall on the women’s heads, sticking to their knit beanies and scarves and catching on their uncovered hair. The women’s mouths are open, as they raise their voices against Ayatollah Khomeini’s new decree. It is the last day they will be able to walk the streets of Tehran without a hijab—and they, along with 100,000 others who joined the protest, are there to be heard.

Hengemeh Golestan captured these women on film 40 years ago as a 27-year-old photographer. She and her husband Kaveh documented the women’s rights demonstrations in early March 1979. This photograph, one of several in her Witness 1979 series, encapsulates the excitement at the start of the Iranian Revolution and the optimism the women felt as they gathered to demand freedom—although their hope would later turn to disappointment. Today, Golestan says, “I still can feel the emotions and power of that time as if it were the present day. When I look at those images I can still feel the sheer power and strength of the women protesters and I believe that people can still feel the power of those women through the photos.”

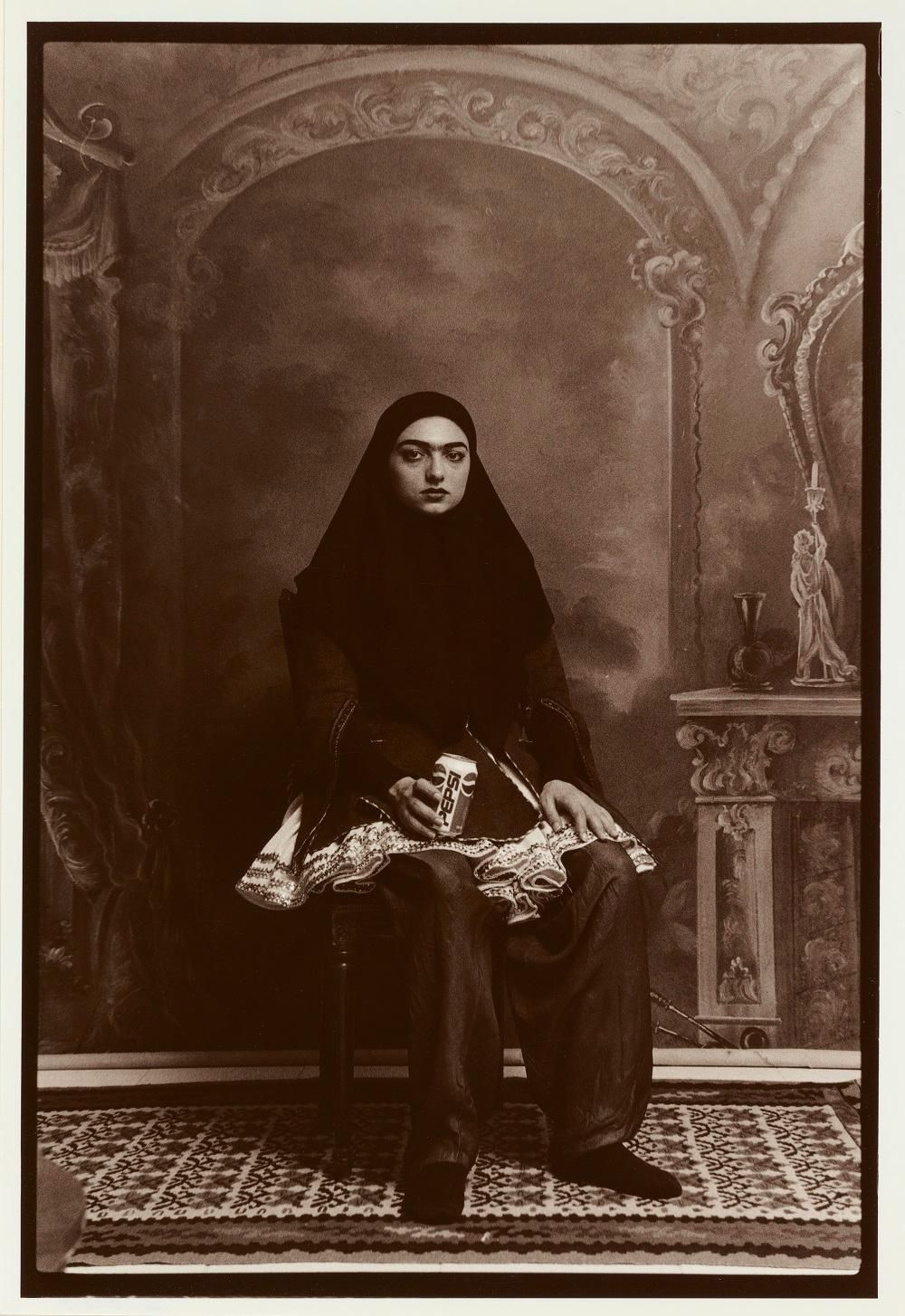

Her photographs are part of the Sackler Gallery exhibition, “My Iran: Six Women Photographers,” on view through February 9, 2020. The show, which draws almost exclusively from the museum’s growing contemporary photography collection, brings Golestan together with artists Mitra Tabrizian, Newsha Tavakolian, Shadi Ghadirian, Malekeh Nayiny and Gohar Dashti to explore, as Massumeh Farhad, one of the show’s curators, says, “how these women have responded to the idea of Iran as a home, whether conceptual or physical.”

Golestan’s documentary photographs provide a stark contrast to the current way Iranian women are seen by American audiences in newspapers and on television, if they’re seen at all. There’s a tendency, Farhad points out, to think of Iranian women as voiceless and distant. But the photographs in the exhibition, she says, show the “powerful ways that women are actually addressing the world about who they are, what some of their challenges are, what their aspirations are.”

Newsha Tavakolian, born in 1981 and based in Tehran, is one photographer whose art gives voice to those in her generation. She writes, “I strive to take the invisible in Iran and make them visible to the outside world.” To create her Blank Pages of an Iranian Photo Album, she followed nine of her contemporaries and collaborated with each of them on a photo album, combining portraits and images that symbolize aspects of their lives. “My Iran” features two of these albums, including one about a woman named Somayeh, raised in a conservative town who has spent seven years pursuing a divorce from her husband and who now teaches in Tehran. Amelia Meyer, another of the show’s curators, says Somayeh’s album documents her experience “forging her own path and breaking out on her own.”

The idea of photo albums similarly fascinated the Paris-based artist Malekeh Nayiny. One of the show’s three photographers living outside of Iran, Nayiny was in the U.S. when the Revolution began and her parents insisted she stay abroad. She only returned to her home country in the 1990s after her mother passed away. As she went through old family photos, some of which included relatives she had never met or knew little about, she was inspired to update these photos to, she says, “connect to the past in a more imaginative way…[and] to have something in hand after this loss.”

Digitally manipulating them, she placed colorful backgrounds, objects and patterns around and on the images from the early 20th century of her stoic-looking grandfather and uncles. By doing this, “she is literally imprinting her own self and her own memories onto these pictures of her family,” explains Meyer. Nayiny’s other works in the show—one gallery is devoted entirely to her art—also interrogate ideas of memory, the passage of time and the loss of friends, family and home.

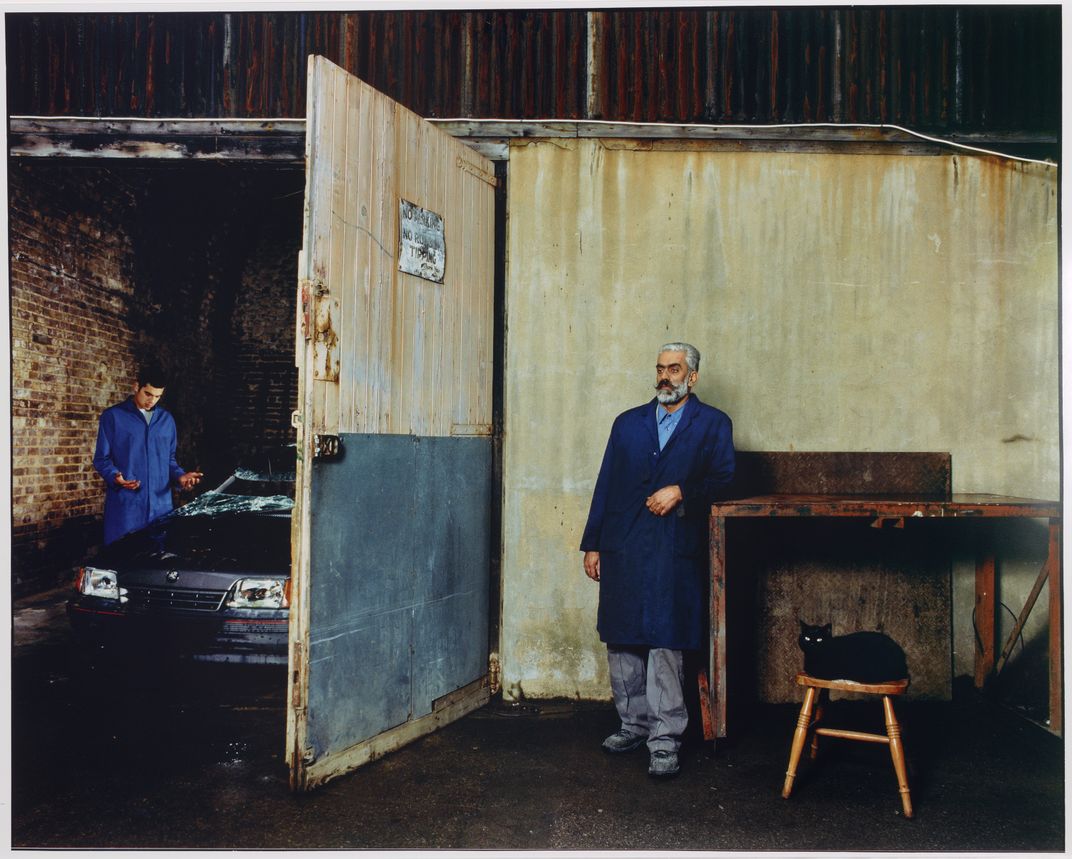

Mitra Tabrizian, who has lived in London since the mid-1980s, explores the feeling of displacement that comes from being away from one’s home country in her Border series. She works with her subjects to create cinematic stills based on their lives.

In A Long Wait, an elderly woman dressed in all black is seated on a chair next to a closed door. She stares at the camera, with a small suitcase by her side. Tabrizian keeps the location of her work ambiguous to highlight the experience of a migrant’s in-betweenness. Her works explore the feelings associated with waiting, she says, both the “futility of waiting (things may never change, certainly not in [the] near future) and a more esoteric reading of not having any ‘home’ to return to, even if things will eventually change; i.e the fantasy of ‘home’ is always very different from the reality of what you may encounter when you get there.”

Besides documentarian Golestan, the artists are working primarily with staged photography and using symbols and metaphors to convey their vision. And even Golestan’s historic stills take on a new depth when viewed in the aftermath of the Revolution and the context of 2019.

The “idea of metaphor and layers of meaning has always been an integral part of Persian art,” says Farhad. Whether it’s poetry, paintings or photographs, the artwork “doesn’t reveal itself right away,” she says. The layers and the details give “these images their power.” The photographs in the show command attention: They encourage viewers to keep coming back, pondering the subjects, the composition and the context.

Spending time with the photographs in the show, looking at the faces American audiences don’t often see, thinking of the voices often not heard offers a chance to learn about a different side of Iran, to offer a different view of a country that continues to dominate U.S. news cycles. Tabrizian says, “I hope the work creates enough curiosity and is open to interpretation for the audience to make up their own reading—and hopefully [to want] to know more about Iranian culture.”

“My Iran: Six Women Photographers” is on view through February 9, 2020 in the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C.