The Visionary John Wesley Powell Had a Plan for Developing the West, But Nobody Listened

Powell’s foresight might have prevented the 1930s dust bowl and perhaps, today’s water scarcities

:focal(1971x1090:1972x1091)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/8d/ed8d42e5-ef92-44f6-a023-ef79c16d055a/npg_70_21-powell-r.jpg)

On January 17, 1890, John Wesley Powell strode into a Senate committee room in Washington, D.C., to testify. He was hard to miss, one contemporary comparing him to a sturdy oak, gnarled and seamed from the blasts of many winters.

Clear gray eyes stared out from a deeply lined face, mostly covered by a shaggy bird’s nest of gray beard, flecked with cigar ash. No one would call the 56-year-old veteran and explorer handsome, but one knew immediately when he entered a room. Only five feet, six inches tall, he spoke rather slowly, but forcefully, with a fearless independence of mind.

When he expressed himself emphatically, the stump of his right arm would bob and weave as if boxing with the ghosts of the war that had maimed him; every once in a while, Powell would reach around his back with his left hand and forcibly subdue it—a movement that invariably silenced a room. It was not often comfortable to watch him, but most always mesmerizing. The authority he radiated even in a room crowded with titanic personalities was palpable.

Only a few years after losing his forearm to a minié ball at the battle of Shiloh, he had organized the most daring exploration in American history. Ten men had climbed aboard puny wooden rowboats and pulled out into the Southwest’s Green and Colorado rivers, then spent three months flying, crashing and bounding through the terrible unknown cataracts of the canyonlands, and, finally, through the Grand Canyon itself, not knowing whether a falls or killing rapid lay around the next bend.

The Promise of the Grand Canyon: John Wesley Powell's Perilous Journey and His Vision for the American West

The son of an abolitionist preacher, a Civil War hero (who lost an arm at Shiloh), and a passionate naturalist and geologist, in 1869 John Wesley Powell tackled the vast and dangerous gorge carved by the Colorado River and known today (thanks to Powell) as the Grand Canyon.

Six men came out at the other end, barely alive, half naked, with only a few pounds of moldy flour between them. The experience had changed Powell—and he had become a great American hero.

Now, two decades later, Powell had come to testify not as a hero or explorer, but as one of America’s foremost scientists, the head of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and an architect of federal science. He had something deeply important to communicate about America’s future.

The Senate Select Committee on Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands was the gatekeeper of an issue pivotal to the development of the nation—through them the federal government could bring water to the western deserts and thus open great new lands to new generations of pioneers.

The committee was composed mostly of senators from western states devoted to fulfilling their constituents’ dreams of a home and ever-increasing affluence. They wanted to hear from Powell—arguably the most comprehensively knowledgeable person about those still-little-understood western lands. They craved to hear that irrigation works would bring an Eden to the West, vouchsafing the vision of Manifest Destiny—to push across the continent with wealth and industry bringing to blossom whatever they touched.

But Powell would not tell them what they wanted to hear.

He told them all too rightly that the West offered not enough water to reclaim by irrigation more than a tiny fraction of its land. Their dreams of a verdant West needed to be tempered and shaped to reality. Powell might as well have told them the Earth was flat. The senators were outraged.

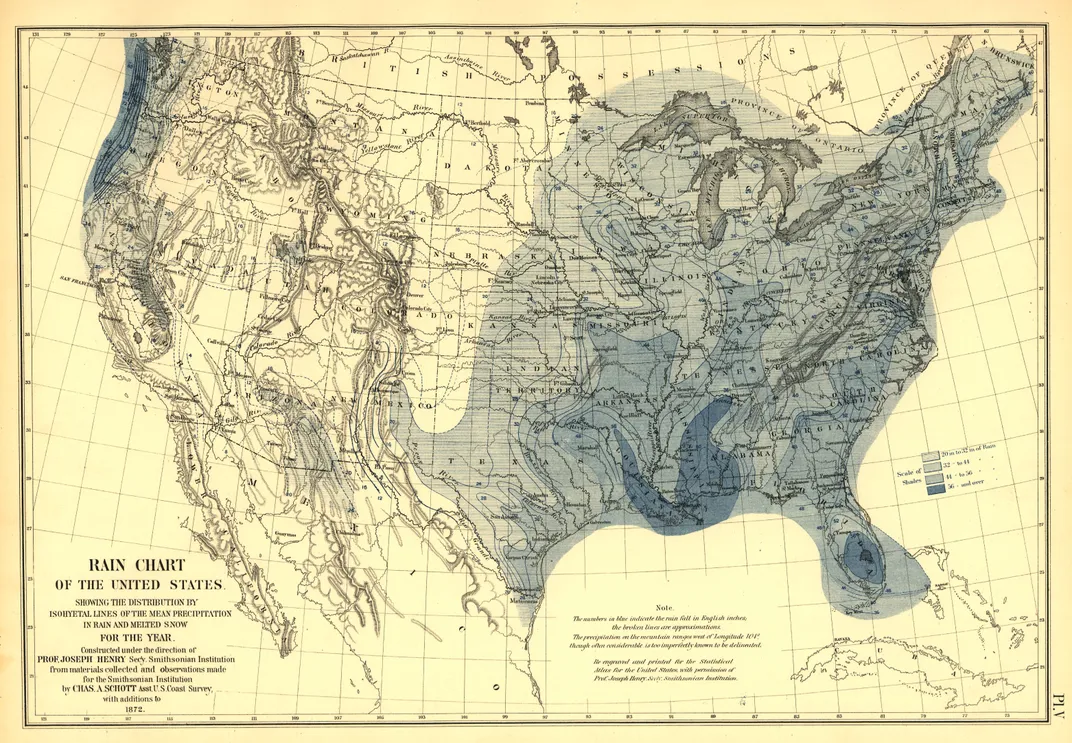

He had brought a map to explain—one of the profoundest such documents ever created in American history. The “Arid Region of the United States” features the western half of the United States, the territory carved up in a jigsaw-puzzle riot of color. Shapes of various sizes, some half the size of states, are colored in oranges, greens, blues, reds, yellows and pinks. It’s a visually stunning.

At first glance, one is captivated purely by its aesthetic. But the significance of a well-designed map—as this one certainly is—comes from the powerful perspective it imparts. Contained within such maps lie reams of fact, conclusions and assumptions, which can often persuade its viewers to confront new, sometimes revolutionary, ways of taking in the world.

Powell’s map, assembled under his direction by USGS cartographers, reveals the western half of America separated into watersheds, the natural land basins through which water flows. Each patch represents a watershed—a hydrographic basin—where all rainfall drains into a common outlet.

Powell understood that a mountain ridgeline determined the flow of water into larger rivers and finally into the sea. Two drops of rain hitting the ground only inches apart along the Continental Divide, which runs along the crest of the Rockies, could travel far different directions. One raindrop might eventually reach the Pacific, while the other could flow into the Atlantic or Arctic oceans.

This marked the first time that a map had been used to visualize a complex intersection of geographical factors—integrating water and land into a nuanced understanding of the Earth’s surface. It was the country’s first ecological map, building on, but pushing far beyond, earlier efforts that century.

Previous maps had mostly defined the nation by political boundaries or topographic features. Powell’s map forced the viewer to imagine the West as defined by water and its natural movement. For its time, Powell’s map was as stunning as NASA’s photographs of Earth from space in the 1960s. The orderly drawing of Jeffersonian grids and political lines—Powell implicitly argued through this map—did not apply in the West; other, more complicated, natural phenomena were at play and must be taken very seriously.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/45/2e45b4e4-27fc-4648-b994-e8a9e3f7d22f/30_stewartportrait.jpg)

Powell would use this map to unfold an argument that America should move cautiously as it plumbed its natural resources and developed the land—and to introduce the idea of sustainability and stewardship of the Earth. In that Senate room, the immensely powerful William Stewart from Nevada listened to Powell, and the more he heard, the more it grated against everything he stood for.

In that gilded age, Manifest Destiny meant riches were there for the taking, enshrined as a divine promise to America. Powell would proffer a wholly new outlook by claiming that Americans needed to listen not only to their hearts, pocketbooks and deep aspirations, but to what the land itself and the climate would tell them. Stewart and Powell would lock into a titanic struggle over the very soul of America—the future of the American West and the shape of the nation’s democracy.

America’s story had always closely aligned with that of Exodus—the tale of a people who left behind an oppressive Old World to enter a wilderness and ultimately build a divinely inspired, promised land. How would that promise look? Powell singlehandedly tried to change the American narrative.

This one-armed scientist-explorer threw down a gauntlet that remains essential and important for the time we live in. Not only for the drought and water shortage now afflicting the West, but for the larger world of climate change. While cautionary, it also offers a clear way forward.

From THE PROMISE OF THE GRAND CANYON by John F. Ross, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by John F. Ross.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.