Walker Evans Wrote the Story of America With His Camera

One of the greatest historians of 20th-century America was a man who used his camera to stare, pry, listen, and eavesdrop

Since before Thucydides until today, those who bring the past into the present generally do so with the written word. But one of the greatest historians of life in 20th-century America was Walker Evans, a man with a camera and an insatiably curious eye.

Evans, who was born in 1903 in St. Louis and died 72 years later, is the subject of a long-overdue traveling exhibition of 120 pictures—a relatively small sample of his remarkable life’s work—organized by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (a Smithsonian Affiliate), the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat in Bottrop, Germany, and the Vancouver Art Galley. The show will be in Atlanta from June 11 until September 11.

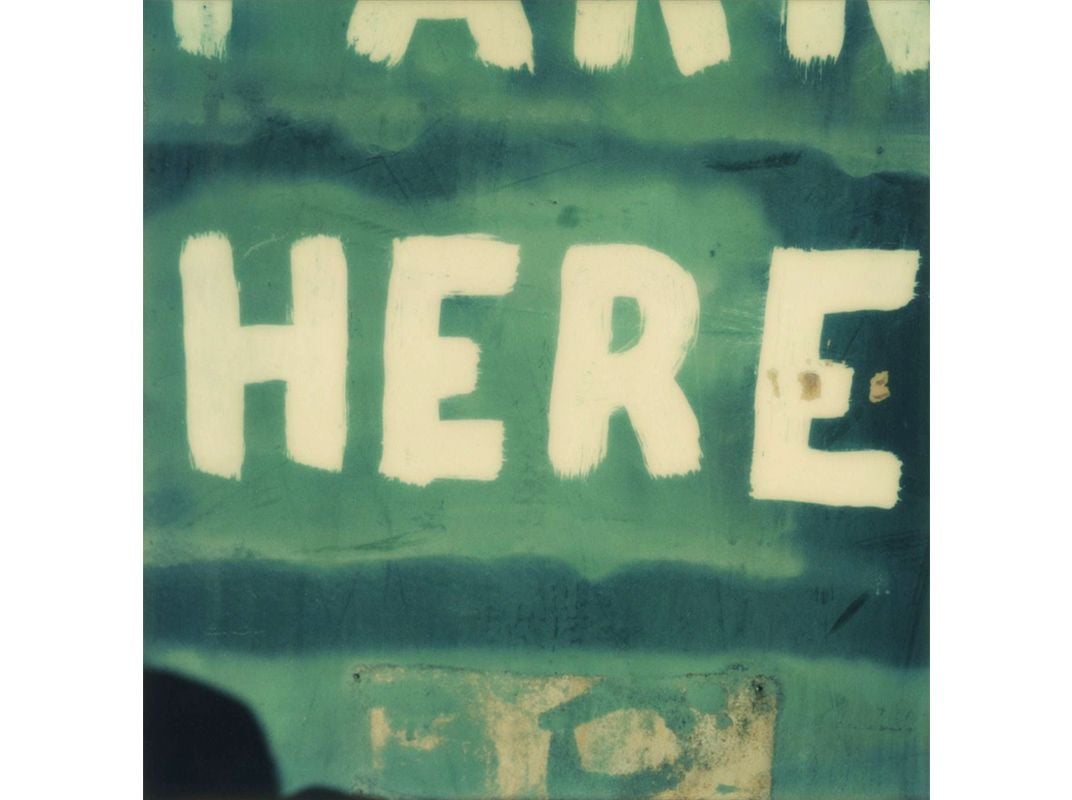

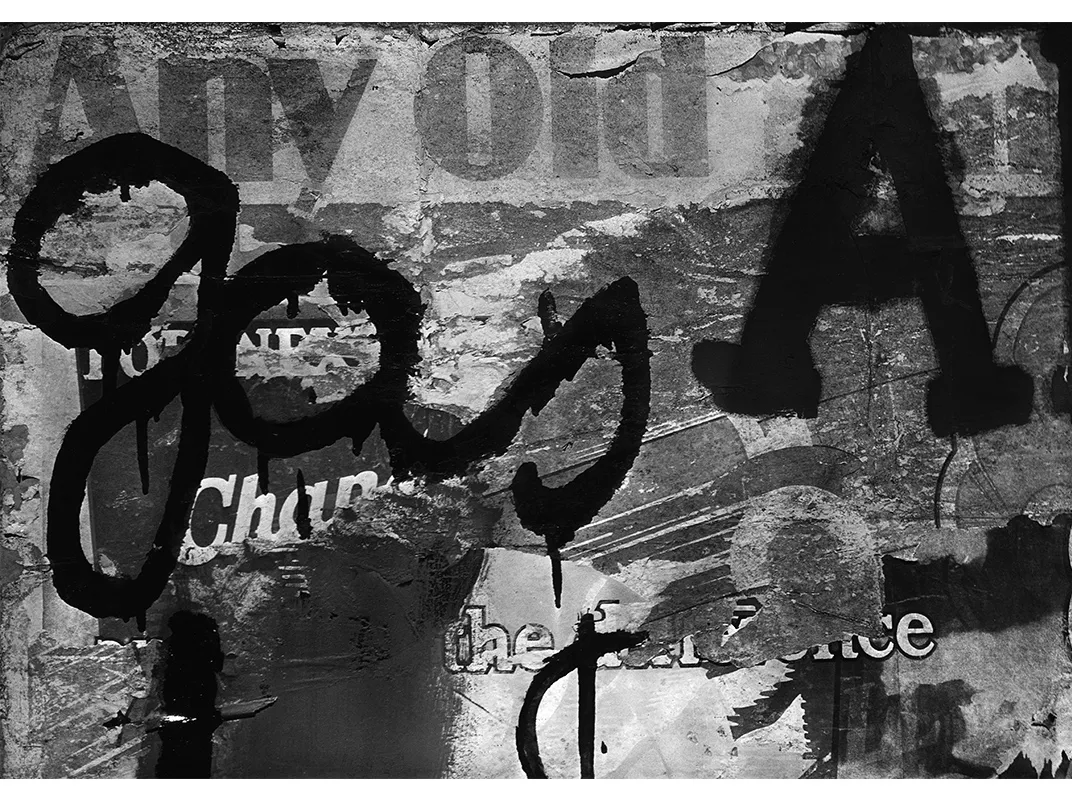

Evans’s credo was as clear and unblinking as his work: “Stare. It is a way to educate your eye, and more. Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop. Die knowing something. You are not here long.”

From early in his career, his eye was educated, but he never stopped learning. Though he did not call himself an artist, as many market-conscious photographers do today (when Evans started taking pictures in the late 1920s, photography was rarely considered an art at all), he produced images as compelling as those of Goya and Hopper.

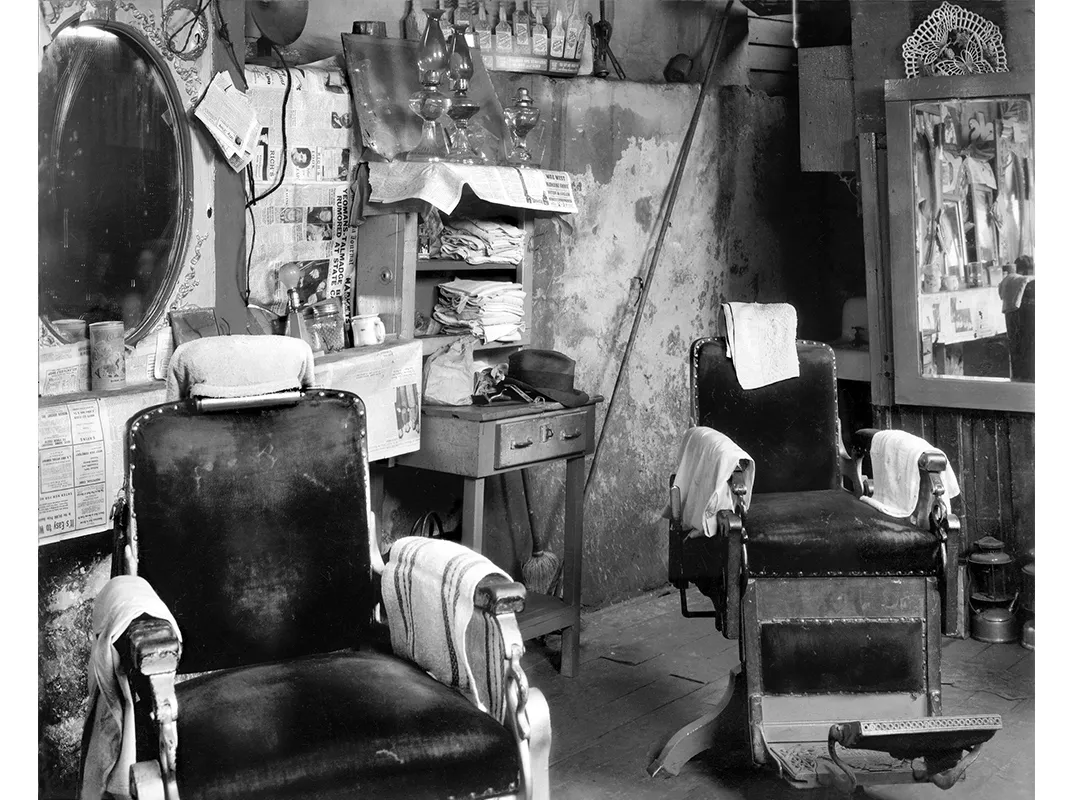

To view the photographs in this compelling exhibition, or in the accompanying book, Walker Evans: Depth of Field by John T. Hill and Heinz Liesbrock, is to look through the eyes and lens of someone who seemed to find everything worth seeing, and no subject, animate or otherwise, unworthy of respect.

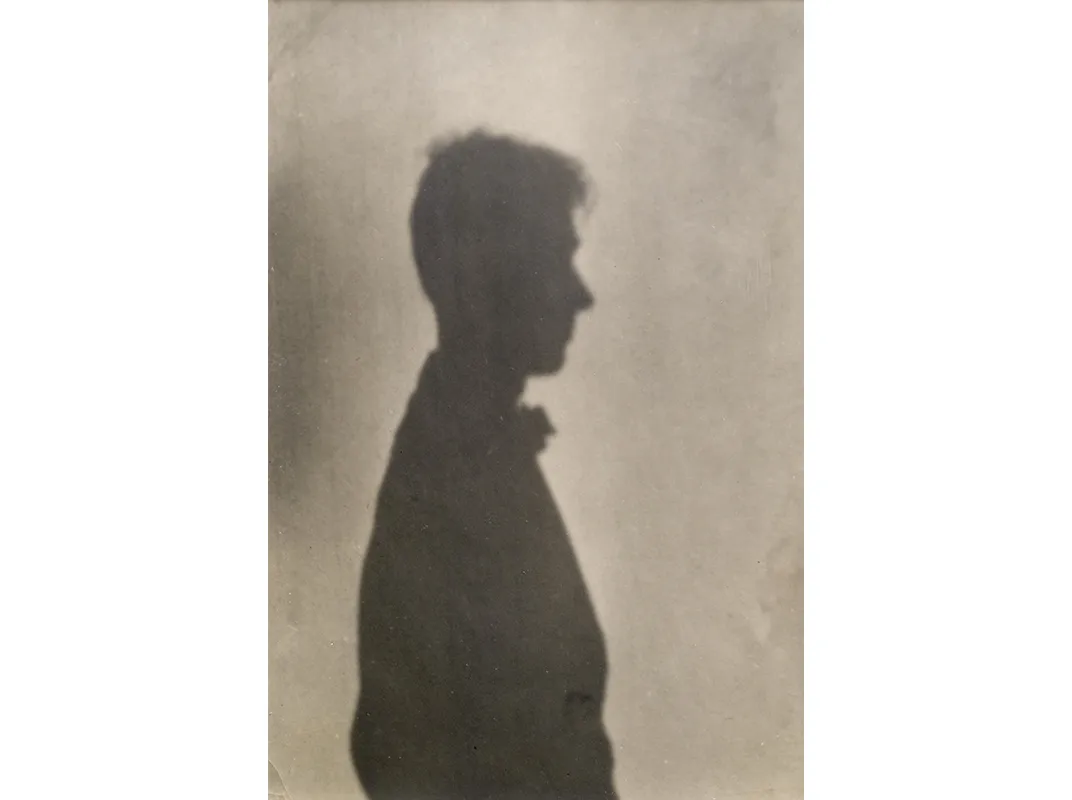

Though Evans is indisputably one of this country’s great photographers, he originally saw his future as a writer. Born into an affluent middle-western family and educated at expensive private schools, he dropped out of Williams College after a year. Naturally, he did what literary hopefuls often did in the Jazz Age; he headed off to Paris.

His revelations in France were as much visual as literary, as it turned out; he encountered the photography of the Frenchman Eugene Atget and the German August Sander, the former known for meticulously documenting the street scenes of old Paris before it was transformed by broad boulevards, the latter for his straightforward portraits of hundreds of his fellow countrymen.

When Evans returned to the States after a year, the lens had replaced the pen in his ambitions, though the writer remained within; he would later call photography the “most literary of the graphic arts.” In his case, it could be described in reverse, as the most graphic of the literary arts.

The great Russian writer Isaac Babel recalled his mother saying to him, “You must know everything.” (In part, this may be because young Isaac was physically small and Jewish in a world filled with Cossacks.) Looking at the breadth of Evans’s vision—at all the things animate and inanimate he stared at and caught on film—it’s not hard to imagine that at some point he said to himself, “You must see everything.”

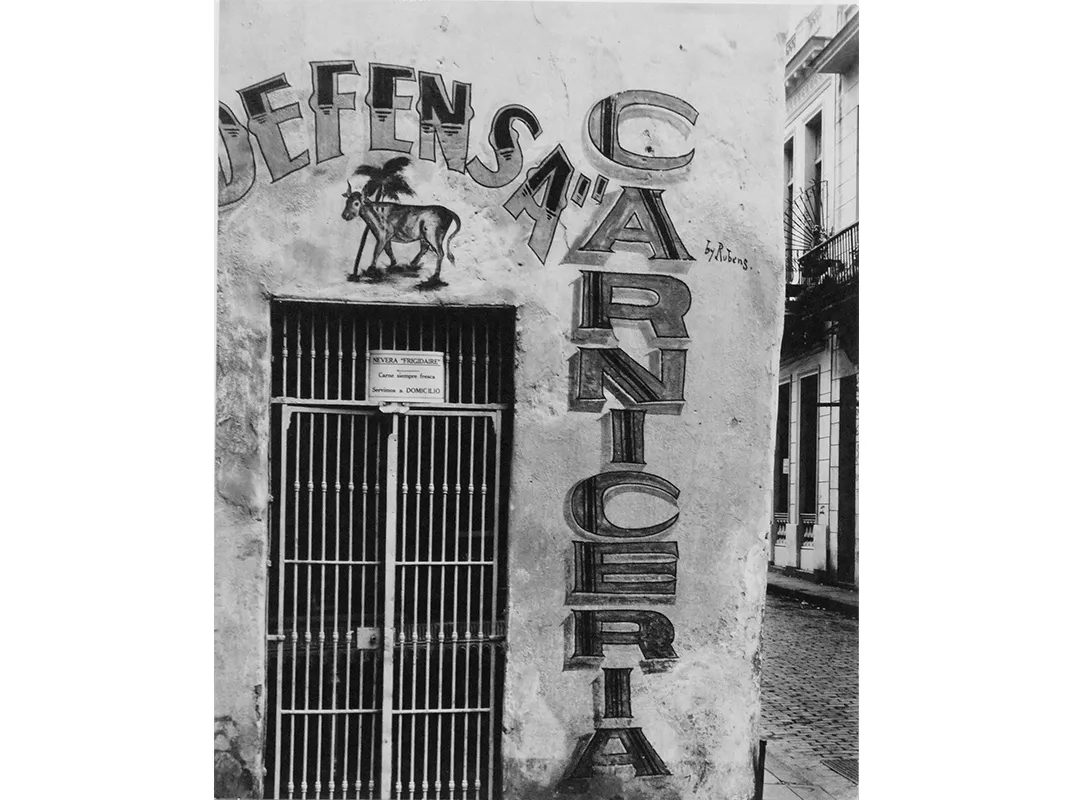

In the course of his career Evans created an intricate tapestry of American life—its architecture, people, commerce, objects and especially its rigors and hardships. Though thought of today primarily as a photographer of people, his first published pictures in 1930 were of architecture, particularly in a book called The Bridge, a long poem by Hart Crane published by Black Sun Press based in Paris.

Evans remained interested in architecture, and the look of cities and towns. The influence of Atget is clear. In what is one of his most evocative pictures, a 1931 view of the main street of Saratoga Springs, New York, on a wet winter day, the line of parked, near-identical black cars, the rain slicked streets, and the graceful arcing of the leafless elm trees, form what is as memorable a description of the pre-war northeastern U.S. as any writer ever accomplished.

While working in the South, he was drawn both to grand and neglected antebellum plantation homes that looked lifted directly from Palladio’s Italy, and to sharecroppers’ shacks, their interiors of raw wood decorated with a kind of hopeful desperation by ads torn out of magazines.

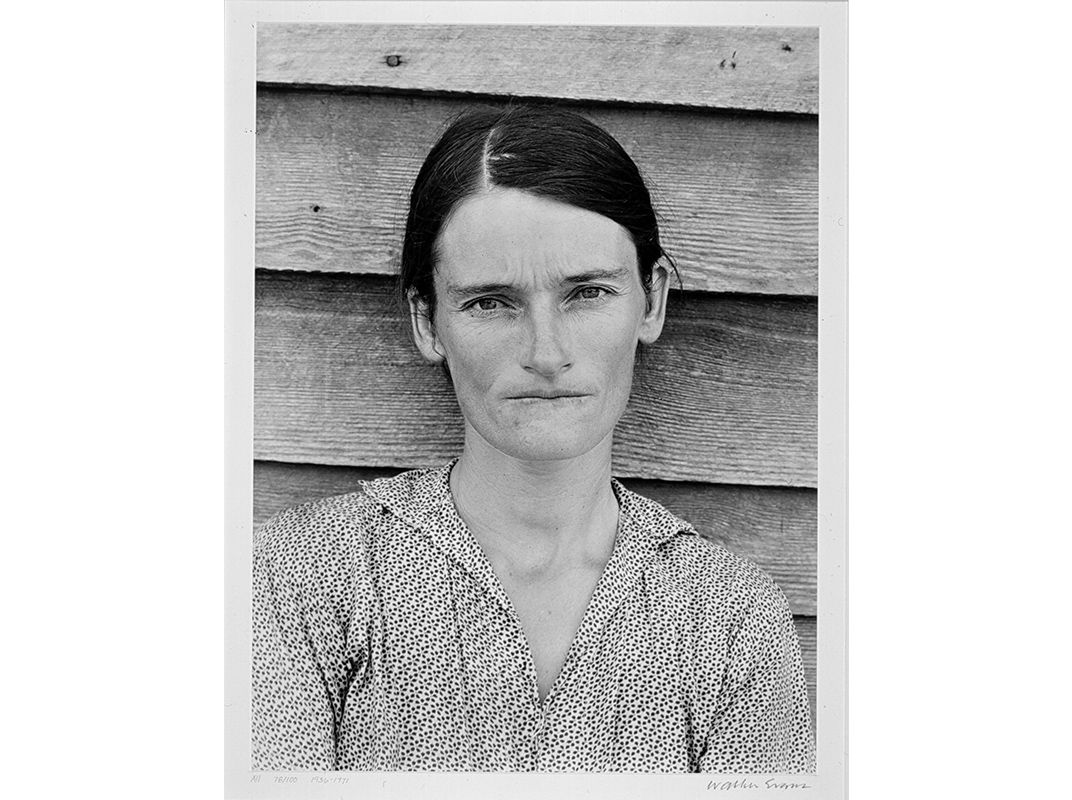

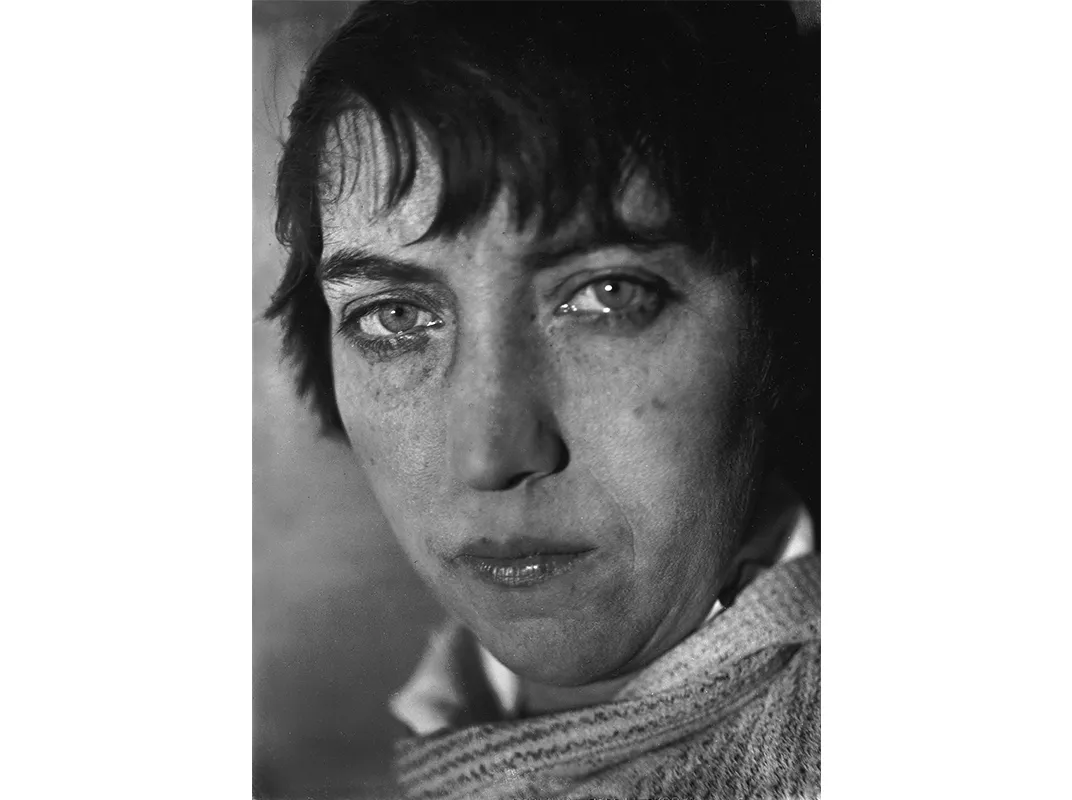

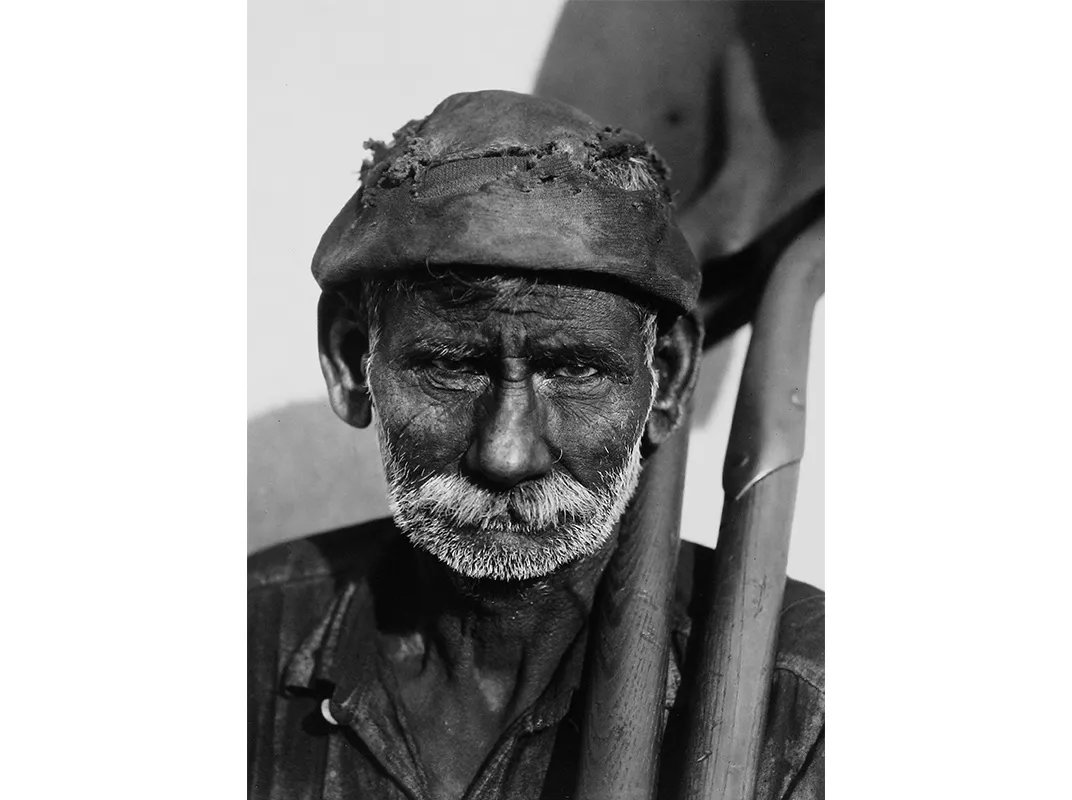

Some of Evans’s best-known and most resonant images are those he made of people down on their luck (but not defeated), using an 8- by 10-inch view camera, while working for the government’s Farm Security Administration from 1935 to 1938.

When he went to work for the FSA, in economically disastrous and politically charged times, he declared that his work would reflect “no politics whatever.” But even if his portraits of sharecroppers and stressed families were less purposefully poignant than those of such colleagues as Ben Shahn and Dorothea Lange, they reported on the plight of ordinary Americans in a way that is powerfully empathetic.

Brett Abbott, curator of the exhibition at the High Museum, told me that Evans’s “approach to portraiture was quiet and direct, endowing his subjects with dignity and grace.”

Perhaps his most famous picture from this period was of a tenant farmer’s wife in Alabama, a subtly touching portrait that came to be regarded as the Appalachian Madonna, and rather than a vision of anguish, the woman seems instead to be mildly amused to be in front of the camera of this inquisitive Yankee (hence the tentative Gioconda smile). But the unstinting stare of his camera, however objective he meant it to be, portrays with obvious feeling the plight of the economically dispossessed.

The weathered, careworn faces of hardscrabble farmers, etched by relentless uncertainty, are an eloquent history of sun-bleached dark days. Some of the most affecting scenes in Arthur Penn’s 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde echo the mood of these photographs, and were perhaps influenced by them. Even when he looked away from faces and families, Evans was able to express the ebb tide of the times. A pair of worn working boots standing unused on the unforgiving soil of Hale County, Alabama, mutely reveals the state of life in that place at that time (1936). And a photograph of a small child’s grave dug into the rock hard earth and topped by a small plate, perhaps for donations, is as heartfelt as any photograph in the show and book.

Evans’s FSA work may have the most emotional gravity in the exhibition, but the breadth of his work is what most impresses. As Brett Abbott says, “the FSA work is important in the Atlanta show, especially because it was done in the South. But the show’s larger aim is to place that iconic imagery within the context of Evans’s work as a whole, including early work on the streets of New York and later work in which he plumbed the creative possibilities of candid capture portraiture.” Some of this later work, done surreptitiously on New York subways, has an effect no less haunting than the pictures in the Depression-era south.

Evans also worked for Fortune magazine. For one assignment, the magazine paired him with the writer Thomas Agee, and out of their collaboration came a body of work and a book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. This title, taken from Ecclesiastes, was richly ironic, given that the pictures show men and women who were far from famous. However, the attention paid to these otherwise forgotten Americans by Evans and Agee was in itself an enduring form of praise.

Perhaps the purest manifestation of Evans’s stare is the still life “portraits” of simple tools he made for Fortune in 1955. These pictures of wrenches, pliers and other standard elements in countless toolboxes, placed against a pale gray background, seem completely free of any artistic manipulation; Evans honors the pure utility of these tools, and the pictures by extension honor work, the design ethic, and the manufacture of unglamorous but needed things. The wise fox told Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince that “the essential is invisible to the eyes.” But here Evans truly makes the essential quietly evident.

In a sense, all photography bends toward being history, whether it depicts a Civil War battleground or simply what we looked like as three-year-olds. But Evans was always keenly aware that the split seconds his camera was capturing would tell their stories to future Americans. As Brett Abbott says, “his pioneering ‘lyric’ style was elegant, subtle and direct, fusing a powerful personal perspective with an objective record of time and place.”

What more can we ask of an historian? In the "Divine Comedy," Beatrice says to Dante: “beatitude itself is based on the act of seeing.” After dwelling on these transcendent photographs, I’m inclined to think that sainthood may be in order for the man who made them.

“Walker Evans: Depth of Field” is on view June 11-September 11, 2016, at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)