Walter “Fritz” Mondale served as vice president during one of the bumpiest presidencies in the last half of the 20th century, and four years later, he suffered one of the greatest losses in a presidential election. Nevertheless, when he died Monday at 93, he left behind a solid legacy of promoting liberal causes, reshaping the vice presidency, and creating a role for women in presidential politics.

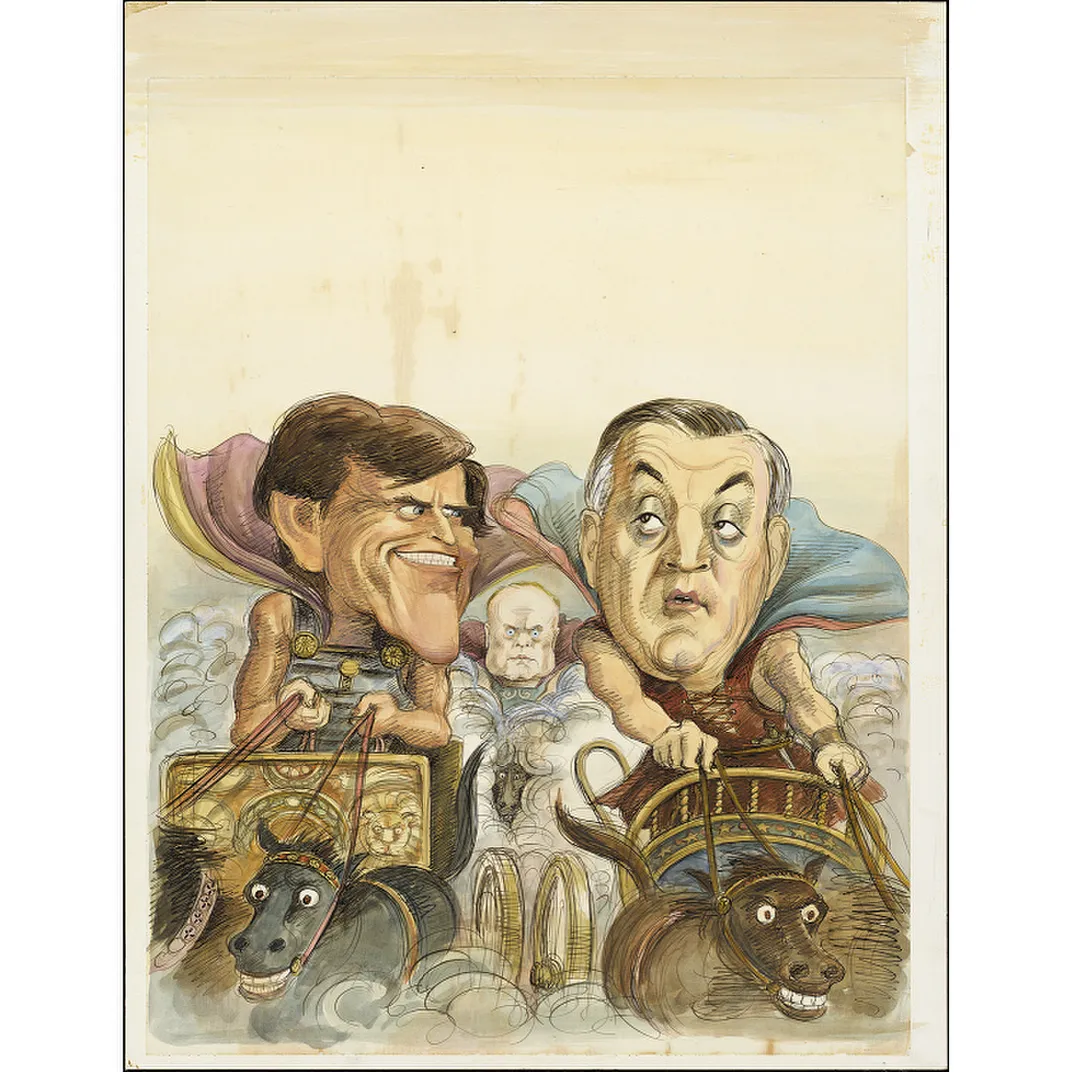

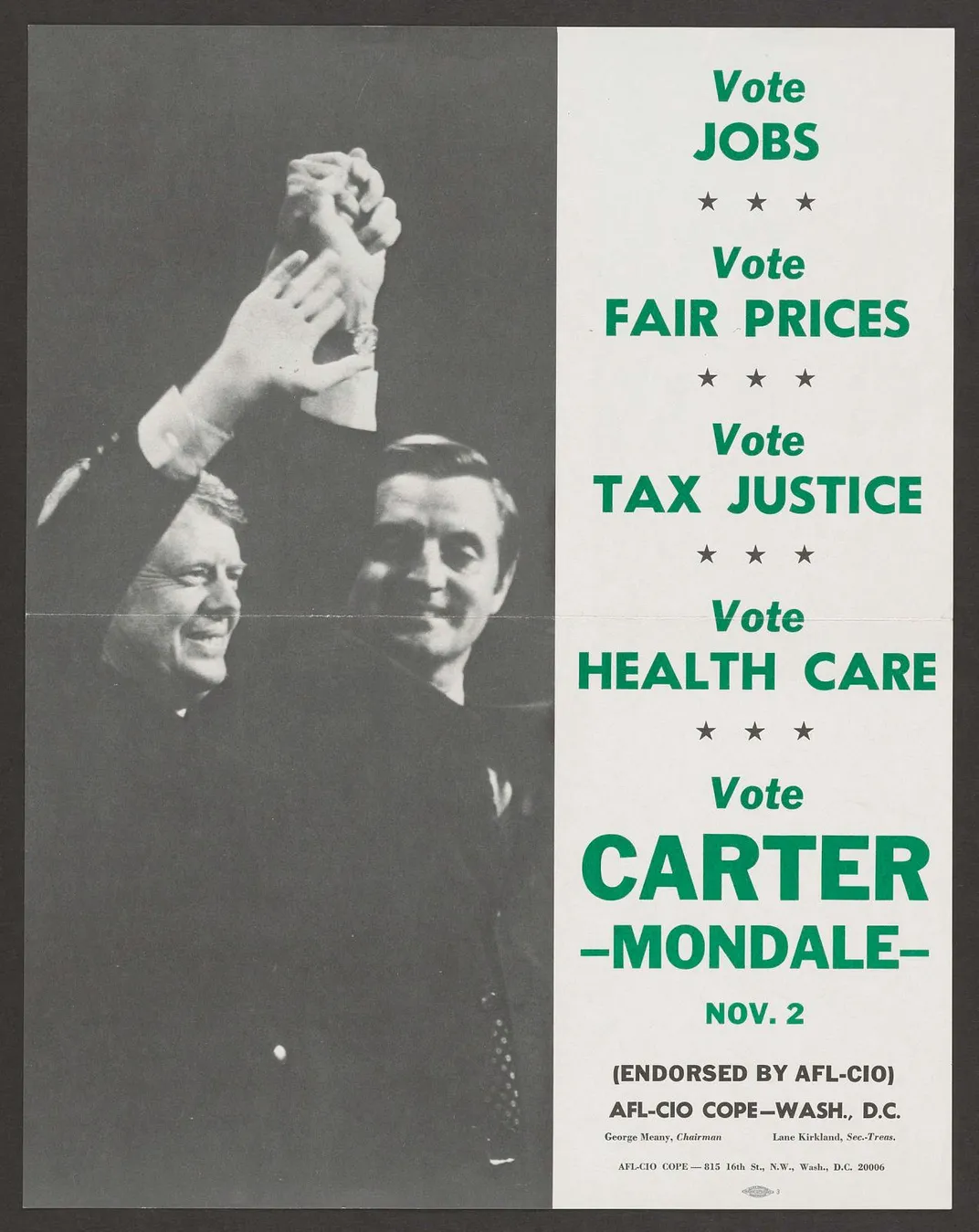

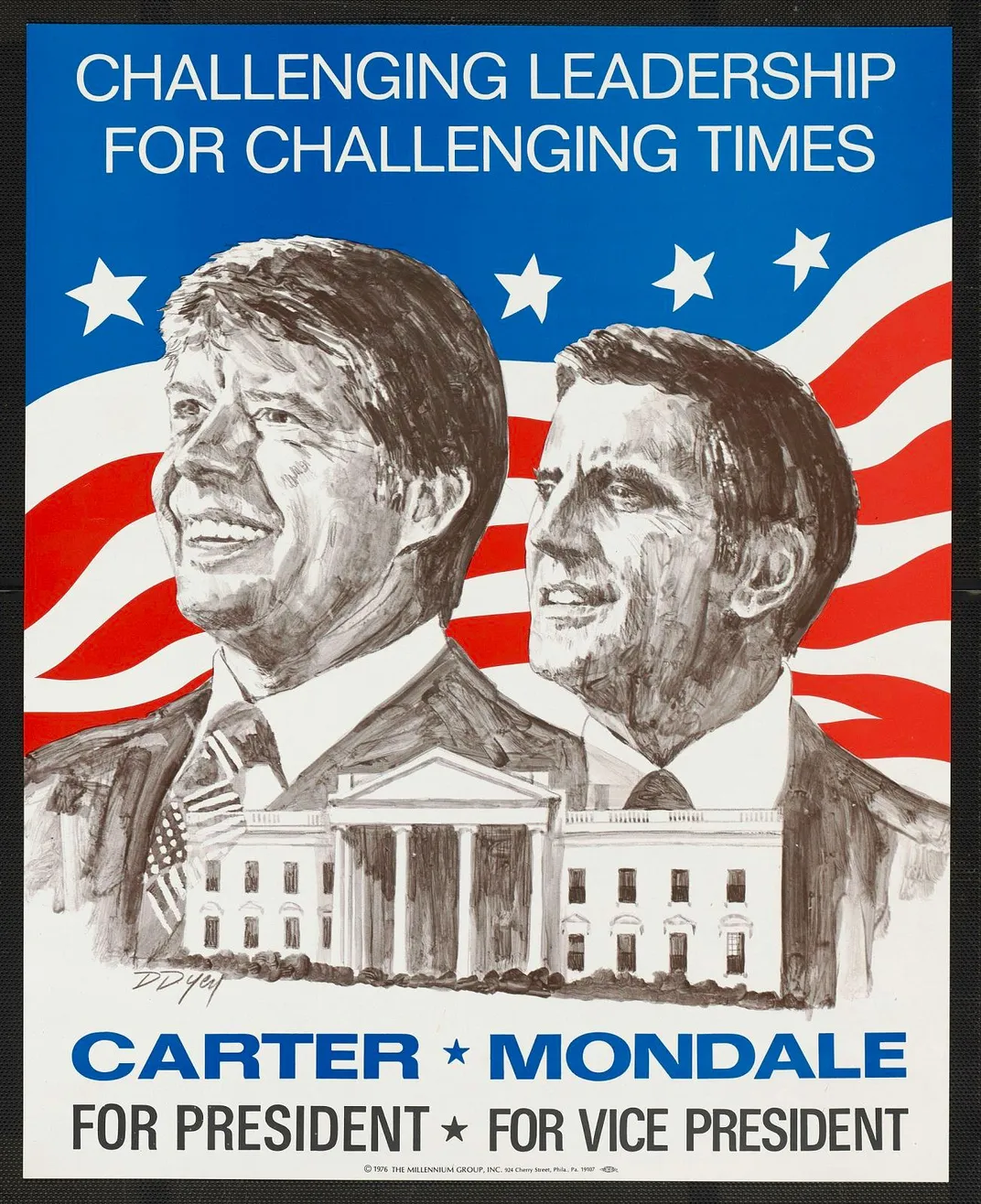

At the Smithsonian, this upbeat politician’s long career is well-represented in the holdings of the National Museum of American History and the National Portrait Gallery. Artifacts include campaign buttons and signs, editorial cartoons, photographs, portraits and correspondence. A 1984 photograph now resides on the Portrait Gallery’s “In Memoriam” page depicting Mondale alongside his running mate Geraldine Ferraro during their 1984 presidential campaign. The apparently relaxed pair look happy as they take shelter beneath an umbrella. Diana Walker is the photographer who produced the image and donated it to the museum.

Mondale first came to Washington as a U.S. senator in 1964, replacing his mentor Hubert H. Humphrey at the time Humphrey moved into the vice presidency. As a lawmaker, Mondale made his mark by being a strong supporter of civil rights on a range of issues from school integration to fair housing. He also endorsed government assistance on consumer protection, health care and childcare. Mondale served 12 years in the Senate before becoming Jimmy Carter’s vice president in 1977.

Carter had defeated President Gerald Ford in the wake of the Watergate scandal that brought down Richard Nixon and aroused dismay over Ford’s controversial decision to issue a blanket pardon for Nixon. Carter won the Democratic nomination surprisingly easily, but given his lack of Washington experience, he knew that he needed a Washington insider by his side—and Mondale fit well into that role.

The Carter years were cursed by an energy crisis, double-digit inflation and a tug of war with Iran over Americans taken hostage there. Despite these problems, which eventually led to Carter’s defeat in his 1980 re-election campaign, “the Carter-Mondale administration is marked by many historians as one which truly elevated the vice president to a meaningful partner, setting a standard that subsequent administrations had to take seriously even if they did not follow the model closely,” says Claire Jerry, a curator at the National Museum of American History.

Mondale had an office in the White House’s West Wing close to the Oval Office, and during his vice presidency, he helped to bring about the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. He also played a key role in approval of the Panama Canal Treaty, which relinquished U.S. control of the canal on December 31, 1999, and in nuclear arms negotiations with the Soviet Union.

Plagued by a myriad of problems in 1979, Carter decided to make an address to the nation about declining national morale and a growing lack of confidence in his administration—what became known as the “malaise speech.” Mondale strongly opposed this speech, which had been inspired by political consultant Patrick Caddell. After Mondale read the Caddell memo that prompted the planned speech, “Gone were the serene, understated Norwegian demeanor and the joy in politics that he usually exuded,” wrote Stuart Eizenstat, Carter’s chief domestic policy adviser, in his memoir of the Carter years. “He was enraged and even vituperative that a 29-year-old wonder kid was peddling what he considered pop-culture Kool-Aid to the president and first lady based on pseudopsychology.” When Carter followed the speech by ousting several Cabinet members, Mondale was even more dismayed. Nevertheless, when Senator Edward Kennedy launched an effort to wrest the Democratic nomination from Carter, Mondale stood by his president. Carter retained the nomination but lost the election by a landslide to the Republican former California Governor Ronald Reagan, who carried all but six states and the District of Columbia. Third-party candidate John Anderson drained away seven percent of the vote.

Almost as soon as those votes were counted, Mondale began his effort to win the Democratic president nomination in 1984. Though Mondale’s fund-raising efforts overwhelmed his opponents, he still found himself with a serious opponent in Senator Gary Hart of Colorado before gaining the nomination.

“In 1984, Mondale was on the giving and the receiving end of two of the most memorable moments in campaign debate history,” says Jerry. “In a primary debate between five contenders for the Democratic nomination, Mondale got a laugh when he said to Gary Hart: 'When I hear your new ideas, I’m reminded of that ad: Where’s the beef?' a reference to a well-known fast-food ad of the day. The tables turned in the second presidential debate between Mondale and Ronald Reagan. At the age of 73, Reagan was being challenged for being too old to be president. Reagan silenced the critics with 'I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience.' Even Mondale, 17 years younger than his opponent, laughed!”

Though Reagan was a tough and still-popular opponent, Mondale made the biggest news within the campaign season when he chose a woman, former New York Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate. At that convention, she had already broken one barrier: She was the first woman chair of the platform-writing committee. When she appeared before the convention as the vice-presidential nominee, she declared, “If we can do this, we can do anything.” It would be 24 years later before Republican John McCain chose Sarah Palin as his running mate and 12 years after that when Joe Biden chose Kamala Harris, now the first woman vice president. Despite Ferraro’s optimism, Reagan defeated Mondale even more handily than when he beat Carter. Mondale carried only his home state of Minnesota and the District of Columbia.

After defeat, Mondale returned to work as a lawyer until 1993, when he was tapped to serve as U.S. ambassador to Japan during Bill Clinton’s first term as president, and in that role, he helped to work out a deal that would reduce and relocate U.S. military bases in Okinawa after three servicemen pleaded guilty to raping a 12-year-old girl in 1995. In 1998, Clinton again turned to Mondale for assistance, asking him to serve as a special envoy to Indonesia, which was then riven by economic woes.

Mondale served as a regent of the Smithsonian Institution during his vice presidency, and his late wife, Joan, was a strong supporter of the plan to acquire the National Museum of African Art, then existing in a series of Washington rowhouses. When legislation was initiated to make this move, she appeared at the news conference, and a photo shows her playing African drums. The legislation won approval and took effect in 1979. The museum opened in a new location on the National Mall in 1987.

At a time when Ronald Reagan was using charm and humor to turn "liberal" into a dirty word, Walter Mondale never hid the fact that he cared deeply about minority rights, the size of working-class paychecks and the importance of an activist government. However, he did hide at least one thing from the American public: When there were no cameras in sight, he loved to smoke a good cigar.

:focal(260x122:261x123)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/14/5b14e6d3-da0c-434e-aa8b-f6fac744afca/mobile_mondale.png)

:focal(582x251:583x252)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/83/cf8328b2-bcaa-434b-bea1-3a0b76d04ace/mondale_soical.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)