Was the 1968 TV Show ‘Julia’ a Milestone or a Millstone for Diversity?

Diahann Carroll’s award-winning series was a hit, but it delivered a sanitized view of African-American life

:focal(361x310:362x311)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/53/d6533650-575a-4d25-81ef-895fe363994d/diahann_carroll_julia_1969.jpg)

Editor’s Note, October 4, 2019: The Tony Award-winning actress Diahann Carroll has died. Her daughter Susan Kay announced that the much-loved actress died today in Los Angeles of cancer. She won an Academy Award nomination for best actress for her role as Claudine Price in the 1974 film Claudine, but she is best known for her role as Julia Baker in the television series “Julia,” which ran from 1968 to 1971.

The storyline sounds innocuous. A young, well-dressed widow is raising an adorable 5-year-old son in a nice apartment while working as a nurse. However, using that middle-class premise for the first comedy to showcase a black family in 1968 turned "Julia" into a battlefield in the still-ongoing war about how African-Americans are represented on TV today. Squarely situated at an intersection between popular culture and racial politics, "Julia" became a beachhead for critics who insisted that television should not sacrifice African-American authenticity to win viewers.

Battered by criticism about the show’s opulent feel and faced with the daunting task of representing her entire race, the show’s star, Diahann Carroll, struggled for greater realism. “For a hundred years we have been prevented from seeing accurate images of ourselves and we’re all overconcerned and overreacting,” she told TV Guide in December of 1968. “The needs of the white writer go to the superhuman being. At the moment, we are presenting the white Negro. And he has very little Negro-ness.”

When "Julia" premiered on September 17, 1968, millions of Americans welcomed her small family into their living rooms. The show was an instant hit and won Carroll the Golden Globe Award for best actress in a comedy in its first season. A milestone in the history of television, it was the first series with an African-American lead character since the stereotyped "Beulah" and "Amos and Andy" from the early 1950s. But the show “was a sanitized view of African-American life . . . and didn’t really put a clear lens on what integration really meant, or what the African-American experience truly was,” says Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music and performing arts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

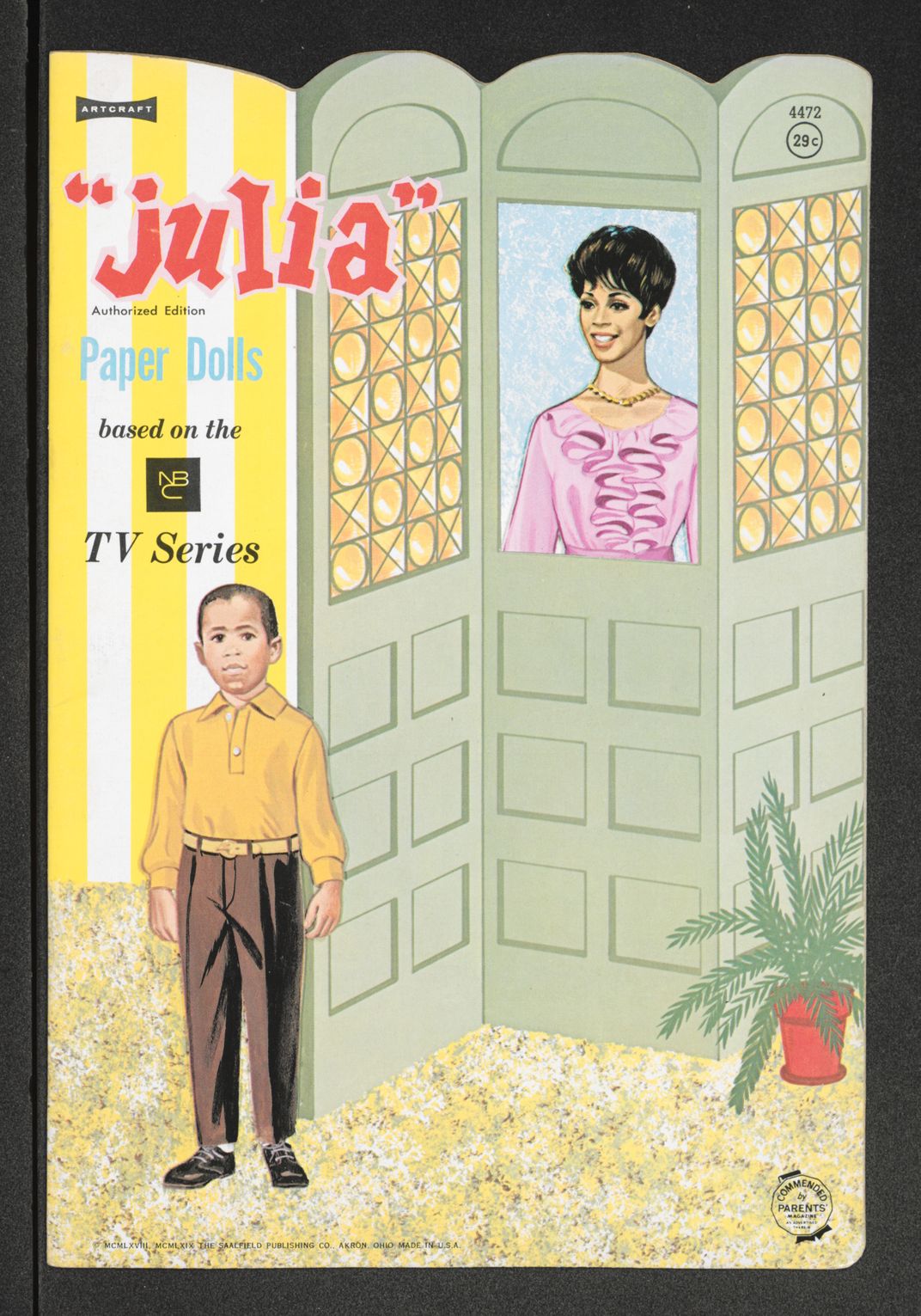

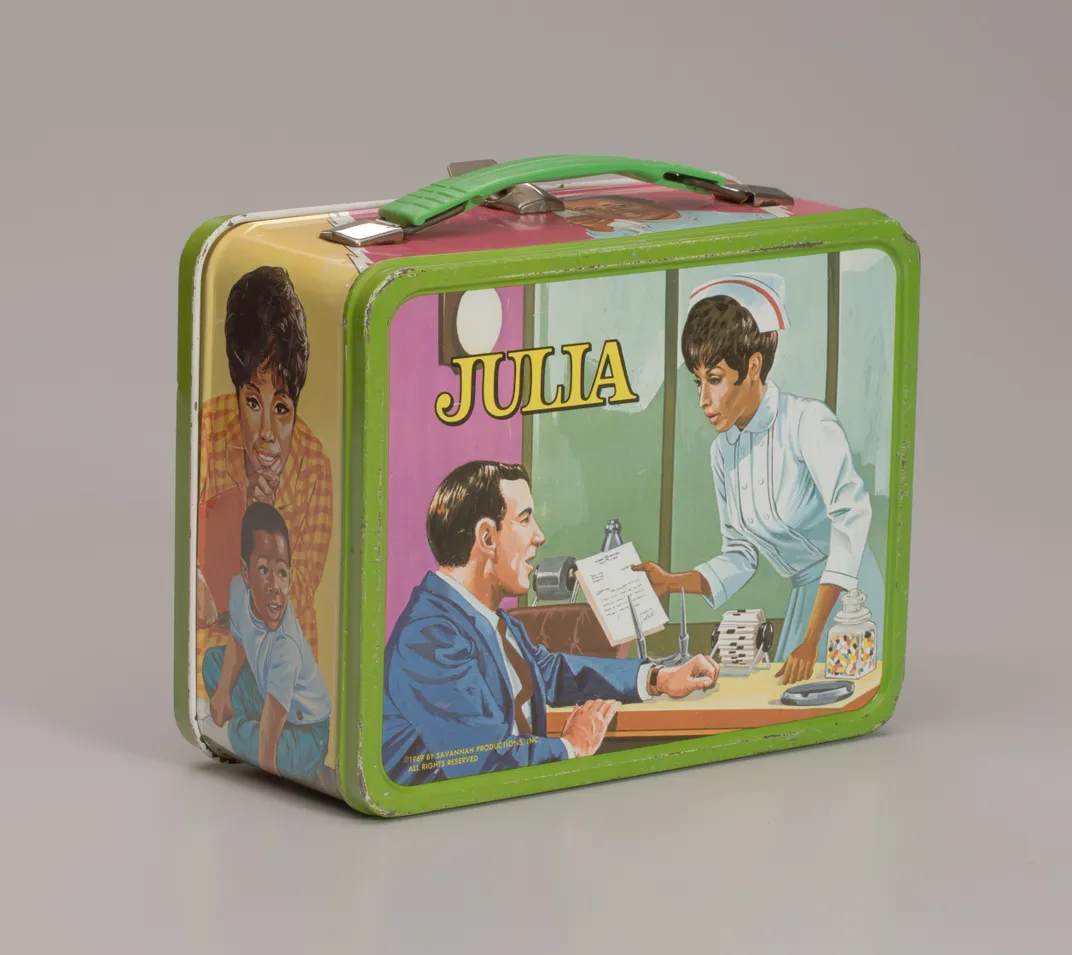

The show's writers did not ignore the reality of prejudice and sometimes portrayed the personal effects of racism, but its plot-lines revolved around middle-class family life—not the plight of African-Americans. "Julia," says Reece, who remembers owning a Julia-themed lunchbox herself as a child, pictured “integration as an easy transition” and provided a false narrative that suggested African-Americans aspiring to the middle class just needed to work hard and find opportunities. This approach ignored “the contextual information that really defines what integration means, and how difficult it is to break through systemic racist policies and practices.”

Some viewers and critics held Carroll responsible for her character’s atypical affluence at a time when one-third of black families lived in poverty. The criticism stung and sent Carroll to the hospital twice with stress-related symptoms. “The racial involvement was very minuscule on all television shows,” Carroll later told PBS, and yet, she felt pressure to justify the dialog, the characters and even the costumes.

Carroll’s African-American predecessors on TV in the mid-1960s were Bill Cosby on "I Spy," beginning in 1965, and a year later, Greg Morris In "Mission: Impossible" and Nichelle Nichols on the original "Star Trek." In all three shows the African-American characters filled fantasy roles—two spies and a space traveler—no more real than the transporters that delivered Capt. Kirk’s crew from the Enterprise to alien planets.

But "Julia" was different. Months before its debut, the show had become a magnet for criticism. In April 1968, Robert Lewis Shayon of Saturday Review called it “a far, far cry from the bitter realities of Negro life in the urban ghetto,” and he continued attacking the show. The naysayers felt that “the suffering was too acute for us to be so trivial . . . as to present a middle-class woman who is dealing with the business of being a nurse,” Carroll recalled in a 2011 Archive of American Television interview. The absence of a father was “a very loud criticism.” This was particularly true among black viewers, one of whom wrote: “I don’t think any more of you for excluding the black man from this series than I think of the ‘original’ slave owners who first broke up the black family! You white men have never given the black man anything but a hard time.”

Carroll had mixed feelings about "Julia." Born in Harlem, she knew the effects of racism firsthand. Her successful career as a singer and an actress provided no shield. On the 1962 Broadway opening night of No Strings in which she starred, she was not invited to the cast party. Even at the height of her career, she watched cabbies pull away when they realized she was not white.

In her new TV role, she saw that “everyone and everything in the script were warm and genteel and ‘nice’—even the racial jokes.” When the show ranked No. 1 in its first week and remained highly rated, “it was such a wonderful feeling to know that I was being accepted into millions of homes every Tuesday night,” she wrote in her autobiography, Diahann! In interviews, she sometimes defended the show, saying that the black middle class was real. She also told Time that “Julia is a comedy, a half-hour sitcom, and there isn’t a half-hour sitcom on television that gives us any real information about anything or anyone!”

On the set and elsewhere, Carroll fought for change. The show’s premise forced her to attempt “to dismantle the limitations of being this character in a public forum, whether through magazine interviews, or media interviews, or the like, really speaking to her own sense of racial consciousness and her own activities, and her awareness of what the limitations of that portrayal really mean to the public’s imagination,” Reece says.

Carroll opposed a scene in which Julia reported that her first experience of racism was as late as her high school prom, and to show how strongly she felt, the actress left the TV lot on the day of the taping. However, with a white male power structure above her, she won mostly small victories. She wanted Julia to wear an Afro, and even that plea was rejected. Between scenes, she met in her dressing room with journalists, psychologists and leaders of organizations who were concerned about the show’s impact. The pressure took a toll. “I cannot spend every weekend studying each word, writing an analysis of everything I think may possibly be insulting, then presenting it to you in the hope that we might come to an understanding,” she told the show’s creator, Hal Kanter. “You can see it—I’m falling apart.” In 1970, she asked to be released from her contract at the end of the series’ third season.

Within a few years, the networks began showing working class African-Americans in comedies like "Good Times" and "Sanford and Son." These views of black life also drew criticism, but from a different perspective: They were accused of failing to investigate the human cost of poverty and perpetuating stereotypes with happy, zany characters. By the mid-1980s, NBC’s top show for six consecutive seasons, "The Cosby Show," depicted the lives of a wealthy African-American family living in circumstances that were far from the norm—another hot topic.

Over the years, the behind-the-scenes power in television has shifted somewhat, providing opportunities for African-American actors to work for black producers, such as Shonda Rhimes and Oprah Winfrey. There are a significant number of African-Americans playing leading roles and among series casts. In 2016, when no actors, producers or screenwriters of color received Academy Award nominations, USA Today found that more than one-third of actors in major-network TV series represented racial or ethnic minorities. In 2017, a GLAAD survey counted characters seen or expected to be portrayed between June 2017 and May 2018, and the LGBTQ advocacy group showed a 4 percent increase in the number of persons of color in character roles, despite a 2 percent decline in blacks featured as regulars in a series.

Today, questions about characterizations of African-Americans on television remain a hot issue. In the 2017-18 TV season, an episode of ABC’s Black•ish was not aired because executives of its production company disapproved. While the exact nature of the controversial content remains unclear, the episode featured comments about black athletes choosing to kneel during the National Anthem at football games as well as unspecified comments on political issues.

As the battle continues, Americans tend to give "Julia" more credit than it received in 1968. Carroll has been recognized during Black History Month, and PBS celebrated her breakthrough in Pioneers of Television. "Julia" touched some lives in a positive way. Debra Barksdale, a sharecropper’s daughter now serving as associate dean of academic affairs at Virginian Commonwealth University School of Nursing, credits the series with inspiring her work. In her office sits Mattel’s Julia doll.

“For the most part, looking back, realizing what we were trying to do at that time, what we were given, the parameters, I feel proud of it,” Carroll said in her National Leadership Project oral history interview. “It made a difference. It was the beginning of a new kind of approach.” Still viewed as a big step in broadcast history, "Julia" is featured in an exhibition at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which displays a jumpsuit costume worn by Carroll. The Smithsonian also holds one of Julia’s dresses, plus "Julia" lunch boxes, a thermos, and paper dolls based on the character.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)