Why the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Makes for a Complicated History

Charged with manslaughter, the owners were acquitted in December 1911. A Smithsonian curator reexamines the labor and business practices of the era

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/f9/7bf99450-7bc1-4a25-a5df-04c228641e47/hpfb29.jpg)

Editor's Note, December 21, 2018: After receiving much critical feedback on this story, we've asked the writer to expand on his thinking and to provide the fuller picture of the legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. The text below has been updated in multiple places and the headline has been updated as well.

One of the most horrific tragedies in American manufacturing history occurred in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911 when a ferocious fire spread with lightning speed through a New York City garment shop, resulting in the deaths of 146 people and injuring many more. Workers—mostly immigrant women in their teens and 20s, attempting to flee—found jammed narrow staircases, locked exit doors, a fire escape that collapsed and utter confusion.

Unable to flee, some workers jumped from the ten-story building to a gruesome death. The tragedy has been recounted in numerous sources, including journalist David von Drehle’s Triangle: The Fire that Changed America, Leo Stein’s classic The Triangle Fire, as well as detailed court transcripts. Readers will be well-served in seeking out these excellent accounts and learning more.

As a curator of industrial history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, I focus on the story of working people. Events like the Triangle fire drive me to keep this important history before the public. The story of workers and the changing social contract between management and labor is an underlying theme of the Smithsonian exhibitions that I have curated.

History is complicated, murky and filled with paradox. Rarely does it rely on simple stories of good and evil or heroes and villains. As scholars uncover the past, bringing depth to historical figures, they also present before readers uncomfortable and difficult questions. What were the tradeoffs that industry, labor and consumers made at the time to accommodate their priorities, as they saw them? Today, as debates continue over government regulation, immigration, and corporate responsibility, what important insights can we glean from the past to inform our choices for the future?

On December 4, 1911, the Triangle Waist Company owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, faced first- and second-degree manslaughter charges after months of extensive coverage in the press. Joseph Pulitzer's World newspaper, known for its sensational approach to journalism, delivered vivid reports of women hurling themselves from the building to certain death; the public was rightfully outraged.

The trial was high drama with counsel for the defense Max Steuer discrediting Kate Alterman, a key witness and survivor of the fire, by convincing the jury that she had been coached and memorized her tale. After three weeks of trial with more than 100 witness testimonies the two men ultimately beat the rap on a technicality—that they did not know a second exit door on the ninth floor was locked—and were acquitted by a jury of their peers. Although the justice system let the families of the workers down, widespread moral outrage increased demands for government regulation.

A similar fire six months earlier at the Wolf Muslin Undergarment Company in nearby Newark, New Jersey, with trapped workers leaping to their death failed to generate similar coverage or calls for changes in workplace safety. Reaction to the Triangle fire was different. More than an industrial disaster story, the narrative of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire has become a touchstone, and often a critique, of capitalism in the United States.

Labor leader Rose Schneiderman moved the public across class lines with a dramatic speech following the fire. She pointed out that the tragedy was not new or isolated. “This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.”

Triangle, unlike other disasters, became a rallying cry for political change. "The tragedy still dwells in the collective memory of the nation and of the international labor movement,” reads the text of an online exhibition from Cornell University's Kheel Center. “The victims of the tragedy are still celebrated as martyrs at the hands of industrial greed."

Yet despite the power of the tragic fire story and dramatic trial, the resulting changes were only first steps in bringing about some needed protection, the underlying American belief in capitalism, including the powerful appeal of the “rags-to-riches” narrative, remained intact. Unlike many other industrial countries, socialism never gained a dominant hold in the United States, and the struggle between labor and management continues apace. As the historian Jim Cullen has pointed out, the working-class belief in the American dream is “… an opiate that lulls people into ignoring the structural barriers that prevent collective and personal advancement.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/12/99126097-0654-4c90-a9d5-103bddc5482b/shirtwaist.jpg)

What is a sweatshop and what was the Triangle Shirtwaist factory like?

Sweatshops were common in the early New York garment industry. An 1895 definition described a sweatshop operator as an “employer who underpays and overworks his employees, especially a contractor for piecework in the tailoring trade.” This work often took place in small, dank tenement apartments. Sweatshops were (and continue to be) a huge problem in the hypercompetitive garment industry.

The Triangle Waist Company was not, however, a sweatshop by the standards of 1911. What is rarely told (and makes the story far worse) is Triangle was considered a modern factory for its time. It was a leader in the industry, not a rogue operation. It occupied about 27,000 square feet on three floors in a brightly lit, ten-year-old building, and employed about 500 workers. Triangle had modern, well-maintained equipment, including hundreds of belt-driven sewing machines mounted on long tables that ran from floor-mounted shafts.

What the Triangle loft spaces lacked, however, was a fire-protection sprinkler system. Without laws requiring their existence, few owners put them into their factories. Three weeks prior to the disaster, an industry group had objected to regulations requiring sprinklers, calling them “cumbersome and costly.” In a note to the Herald newspaper, the group wrote that requiring sprinklers amounted to “confiscation of property and that it operates in the interest of a small coterie of automatic sprinkler manufactures to the exclusion of all others.” Perhaps of even greater importance, the manager of the Triangle factory never held a fire drill or instructed workers on what they should do during an emergency. Fire drills, common today, were rarely practiced in 1911.

Were women organizing at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory?

Even in a legitimate factory, work was often monotonous, grueling, dangerous and poorly paid. Most of the workers killed in the fire were women in their late teens or early 20s. The youngest were two 14-year-old girls. It was not unusual in 1911 for girls that young to work, and even today, 14-year-olds and even preteens can legally perform paid manual labor in the United States under certain conditions. The United States tolerates child labor to a greater extent than many other countries.

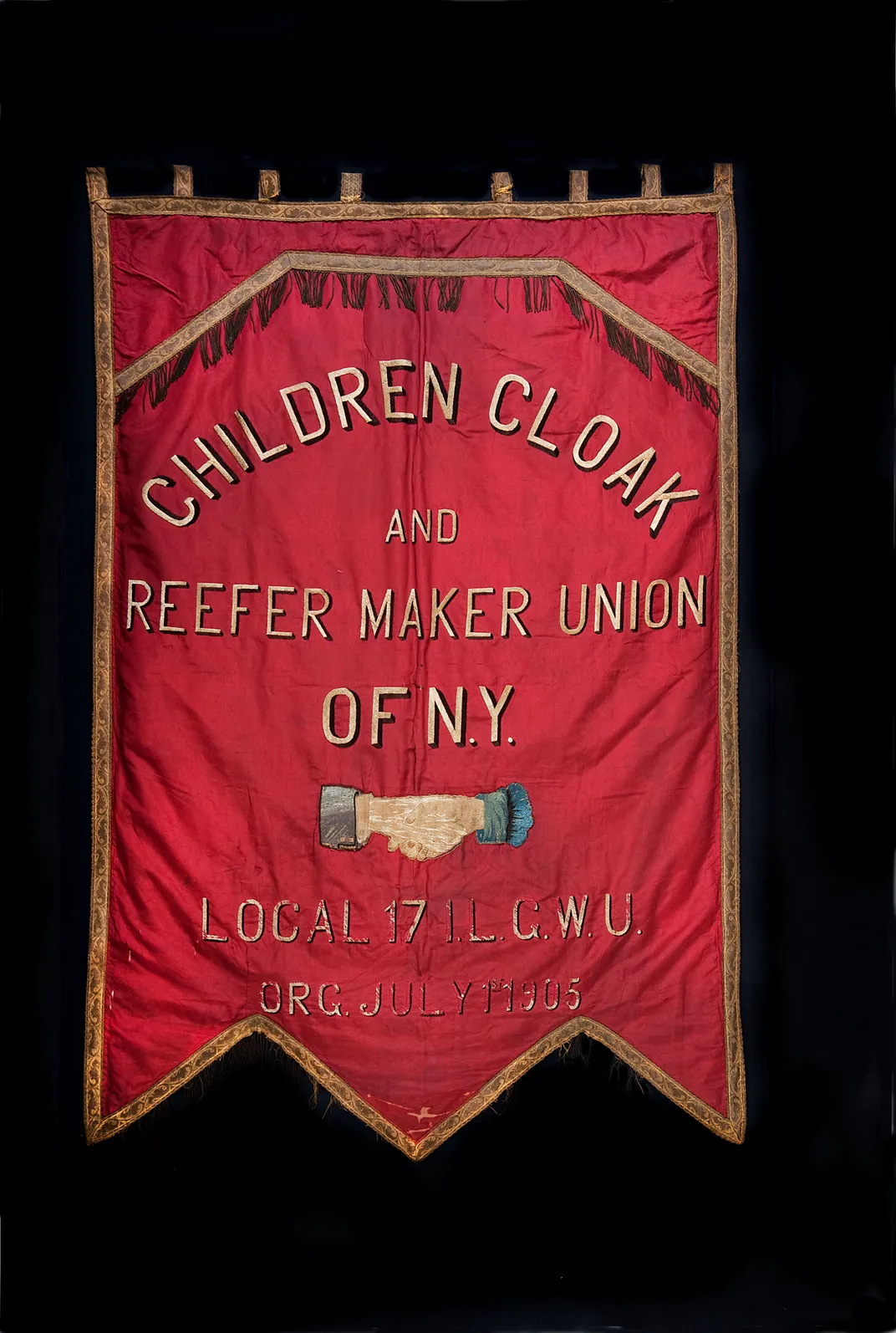

Around 1910, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL) gained traction in their effort to organize women and girls. Labor leaders like Clara Lemlich displaced many of the conservative male unionists and pushed for socialist policies, including a more equitable division of profits. They were up against owners like the Triangle Waist’s Blanck and Harris—hard-driving entrepreneurs who, like many other business owners, cut corners as they relentlessly pushed to grow their enterprise.

What caused the fire?

The media at the time attributed the cause of the fire to the owners’ negligence and indifference because it fit the crowd-pleasing narrative of good and evil, plus a straight-forward telling of the source of the fire worked better than a parsing of the many different bad choices happening in concert. Newspapers mostly focused on the factory’s flaws, including poorly maintained equipment. Court testimony attributed the source of the blaze to a fabric scrap bin, which led to a fire that spread explosively—fed by all the lightweight cotton fabric (and material dust) in the factory.

Like many other garment shops, Triangle had experienced fires previously that were quickly extinguished with water from pre-filled buckets that hung on the walls. Blanck and Harris dealt with fire hazards to their equipment and inventory by buying insurance, and the building itself was considered fireproof (and survived the fire without structural damage). Workplace safety, however, was not a priority for the owners. Workman’s compensation was non-existent at the time. Ironically the nascent workmen’s compensation law passed in 1909 was declared unconstitutional on March 24, 1911—the day before the Triangle fire.

Sadly, the fire was probably ignited by a discarded cigarette or cigar. Despite rules forbidding employees from smoking, the practice was fairly common for men. Few women smoked in 1911, so the culprit was likely one of the cutters (a strictly male job).

The Triangle factory fire gave rise to progressive reformers call for greater regulation and helped change attitudes of New York's Democratic political machine, Tammany Hall. The politicians woke up to the needs, and increasing power, of Jewish and Italian working-class immigrants. Affluent reformers such as Frances Perkins, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Anne Morgan also pushed for change. While politicians still looked out for the interests of the moneyed elite, the stage was being set for the rise of labor unions and the coming of the New Deal. The outrage of Triangle fueled a widespread movement.

What were workers asking for at the time?

In the early 1900s, workers, banding together in unions to gain bargaining power with the owners, struggled to create lasting organizations. Most of the garment workers were impoverished immigrants barely scraping by. Putting food on the table and sending money to families in their home countries took precedence over paying union dues. Harder yet, the police and politicians sided with owners and were more likely to jail strikers than help them.

Despite the odds, Triangle workers went on strike in late 1909. The walkout expanded, becoming the Uprising of 20,000—a citywide strike of predominantly women shirtwaist workers. The workers pressed for immediate needs—more money, a 52-hour work week, and a better way for dealing with the unemployment that came with seasonal apparel change—over more long-term goals like workplace safety.

Blanck and Harris, for their part, were extremely anti-union, using violence and intimidation to quash workers’ activities. They eventually gave in to pay raises, but would not make their factory a "closed shop" that would employ only union members.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/34/62346f95-4765-4482-8762-dd73158b4186/jn2014-3613.jpg)

What laws were in place to prevent tragedies like the Triangle Fire?

The Triangle factory fire was truly horrific, but few laws and regulations were actually broken. Blanck and Harris were accused of locking the secondary exits (in order to stop employee theft), and were tried for manslaughter. Outdated building codes in New York City and minimal inspections allowed business owners to use high-rise buildings in new and sometimes unsafe ways.

In the past, tall buildings warehoused dry goods with just a few clerks working inside. Now, these buildings were housing factories with hundreds of workers. What few building codes existed were woefully inadequate and under-enforced.

After the fire, politicians in New York and around the country passed new laws better regulating and safeguarding human life in the workplace. In New York, the Factory Investigating Commission was created on June 30, 1911. Thorough and effective, the commission had proposed, by the end of 1911, 15 new laws for fire safety, factory inspection, employment and sanitation. Eight were enacted.

What is the most significant lesson of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire?

Better and increased regulation was an important result of the Triangle fire, but laws are not always enough. Today, few realize the role that American consumerism played in the tragedy. At the turn of the century, a shopping revolution swept the nation as consumers flocked to downtown palace department stores, attracted by a wide selection of goods sold at inexpensive prices in luxurious environments. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory workers made ready-to-wear clothing, the shirtwaists that young women in offices and factories wanted to wear. Their labor, and low wages, made fashionable clothing affordable. The uncomfortable truth is consumer demand for cheap goods had pushed retailers to squeeze manufacturers, who in turn squeezed workers.

Seeking efficiency, manufacturers applied mass production techniques in increasingly large garment shops. Industry titans prospered, and even working-class people could afford to buy stylish clothing. When tragedy struck (as happens today), some blamed manufacturers, some pointed to workers and others criticized government. If blame for the horrific events is to be assigned, it must encompass a wider perspective, beyond the faults of two bad businessmen. A broader cancer challenged, and still challenges the industry—the demand for low-cost goods— often imperils the most vulnerable workers.

Deadly workplace tragedies like Triangle still happen today, including the Imperial Food Co. fire of 1991 in North Carolina and the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster of 2010 in West Virginia. While the Triangle fire spurred a progressive movement that enacted many much-needed reforms, the desire today for regulation and enforcement has abated while the pressure for low prices remains intense.

What became of the owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck?

The garment industry, with its low economic bar to entry, attracted many immigrant entrepreneurs. Competition was, and continues to be, intense. Blanck and Harris were both recent immigrants arriving in the United States around 1890, who established small shops and clawed their way to the top to be recognized as industry leaders by 1911. What set them apart from their exploited employees lays bare the grander questions of American capitalism.

Before the deadly fire, Blanck and Harris were lauded by their peers as well as those in the garment industry as the “shirtwaist kings.” In 1911, they lived in luxurious houses and like other affluent people of their time had numerous servants, made philanthropic donations, and were pillars of their community. While Blanck and Harris successfully escaped conviction in the Triangle manslaughter trial, their apparel kingdom crumbled. These men were rightly vilified and hounded out of business. But the system of production largely stayed the same. While the fire did prompt a few new laws, the limited enforcement brought about only a slightly better workplace.

Blanck and Harris tried to pick up after the fire. They opened a new factory but their business was not as successful. In 1913, Blanck was arrested for locking a door during working hours in the new factory. He was convicted and fined $20. In 1914, Blanck and Harris were caught sewing counterfeit National Consumer League anti-sweatshop labels into their shirtwaists. Around 1919 the business disbanded. Harris ran his own small shop until 1925 and Blanck set up a variety of new ventures with Normandie Waist the most successful.

Not surprisingly, the Blanck and Harris families worked at forgetting their day of infamy. Stories were not told and the descendants often did not know the deeds of their ancestors. California artist Susan Harris was surprised, at age 15, to discover her own notoriety—as the granddaughter of an owner of the Triangle Waist Company.

A version of this article was originally published on the "Oh Say Can Your See" blog of the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Peter_Liebhold.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Peter_Liebhold.jpg)