Editor’s Note, August 27, 2019: In the latest Sidedoor podcast, host Lizzie Peabody visits with the New York-based artist David Levinthal in his studio and toured his exhibition, which remains on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through October 14.

At first glance, David Levinthal’s Iwo Jima appears to be a colorized version of the famed image that earned photographer Joe Rosenthal a Pulitzer Prize. But take a closer look, and a number of inconsistencies emerge. Not only is the orientation of Levinthal’s wartime scene reversed, but it also features an unfurled, bullet-riddled American flag and, most importantly, the six Marines raising the flag in the original image are represented by a group of toy soldiers.

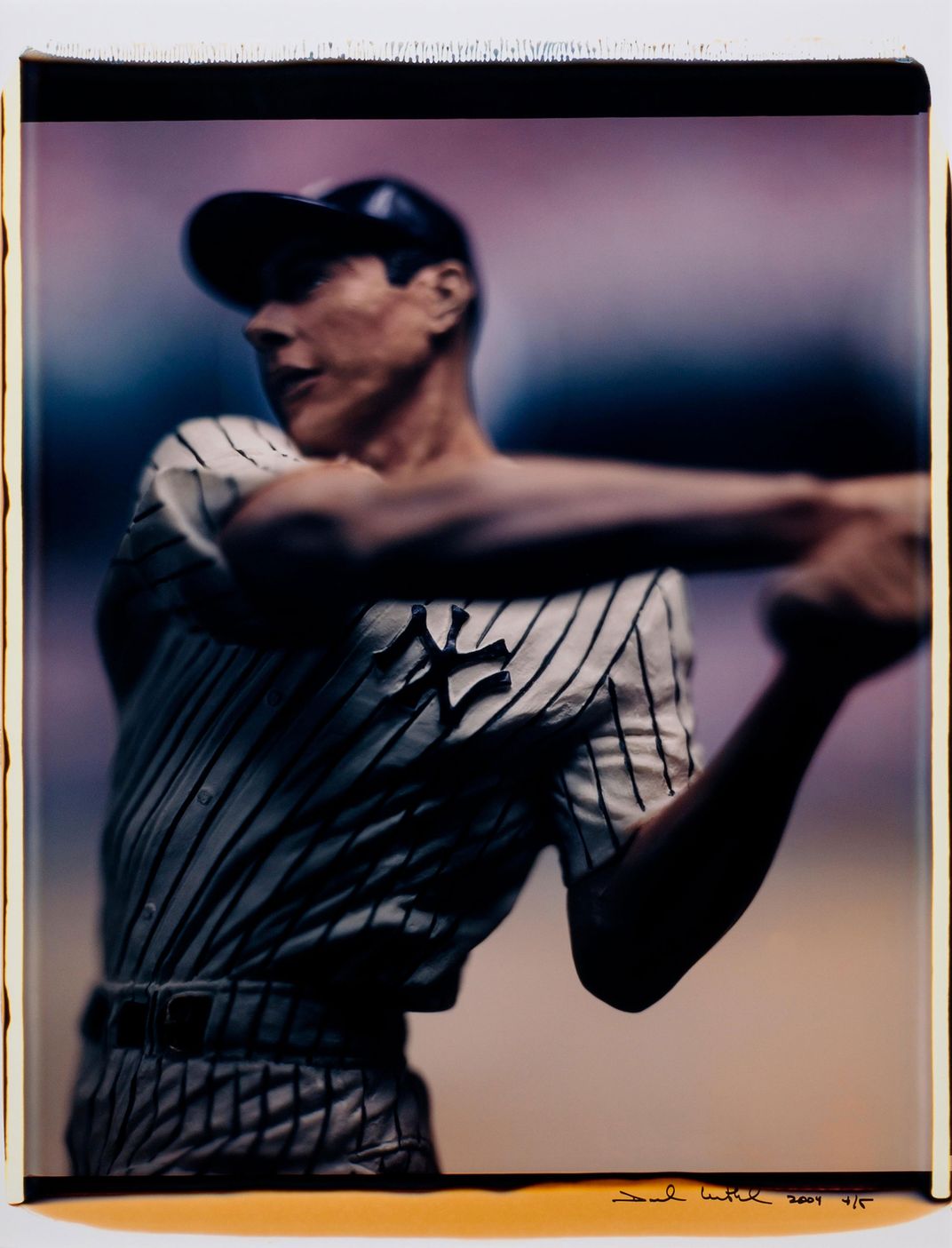

This sense of familiarity, followed by the immediately unsettling realization that nothing is actually as it seems, pervades Levinthal’s oeuvre. As alluded to by the title of a new exhibition, “American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs,” now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the artist’s work relies on an unexpected vehicle—toys, including plastic cowboys, athletes, Barbies and pin-up models—to reveal the constructed nature of some of the foundational aspects of national identity.

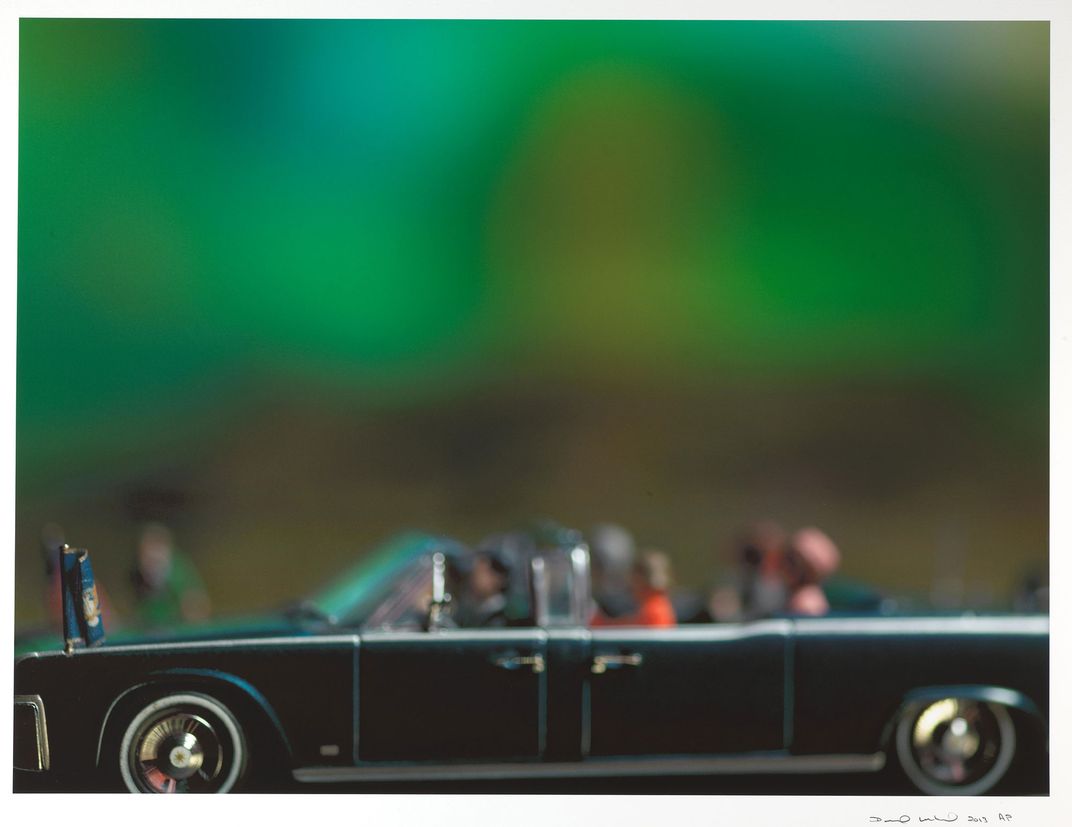

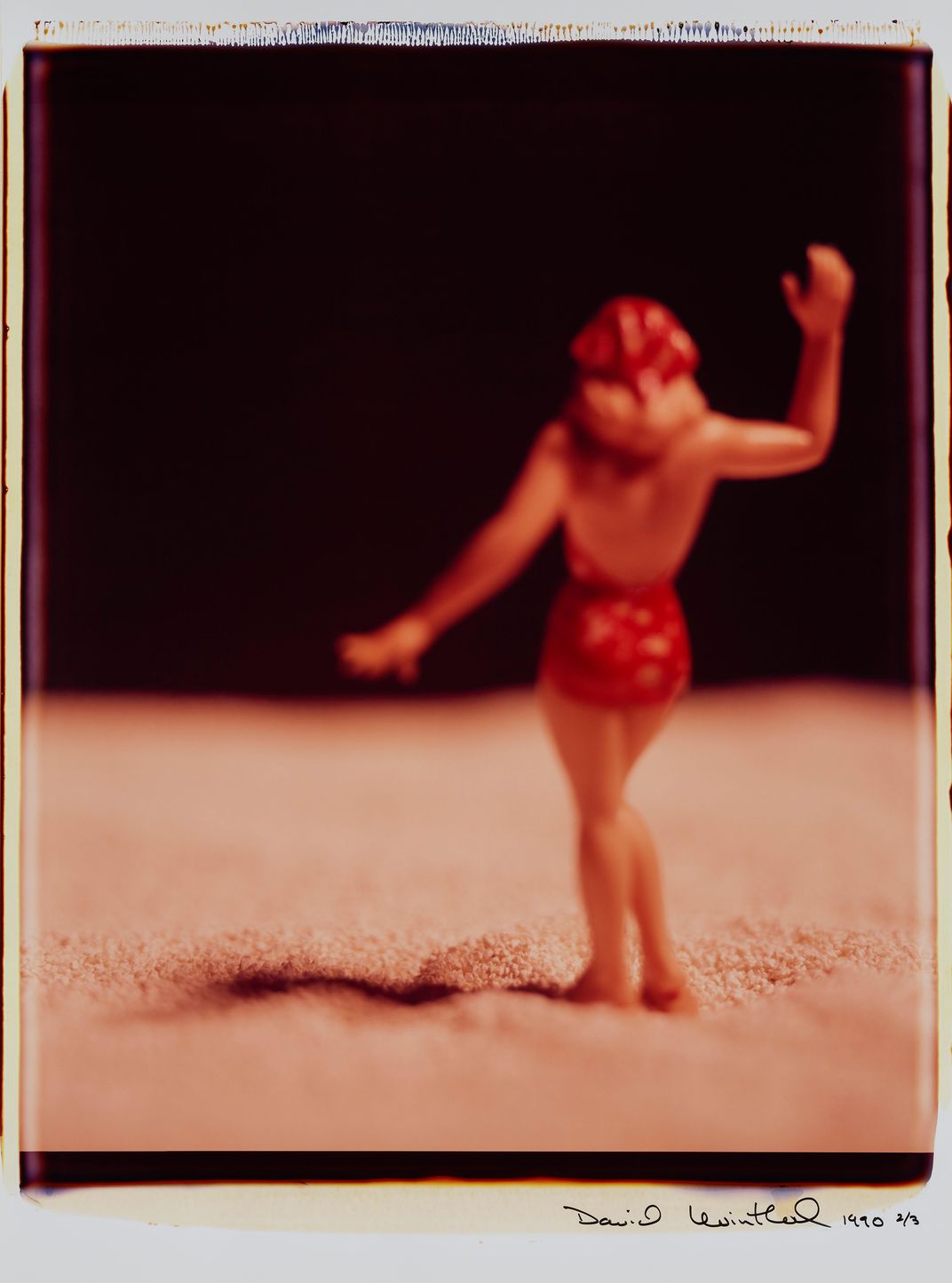

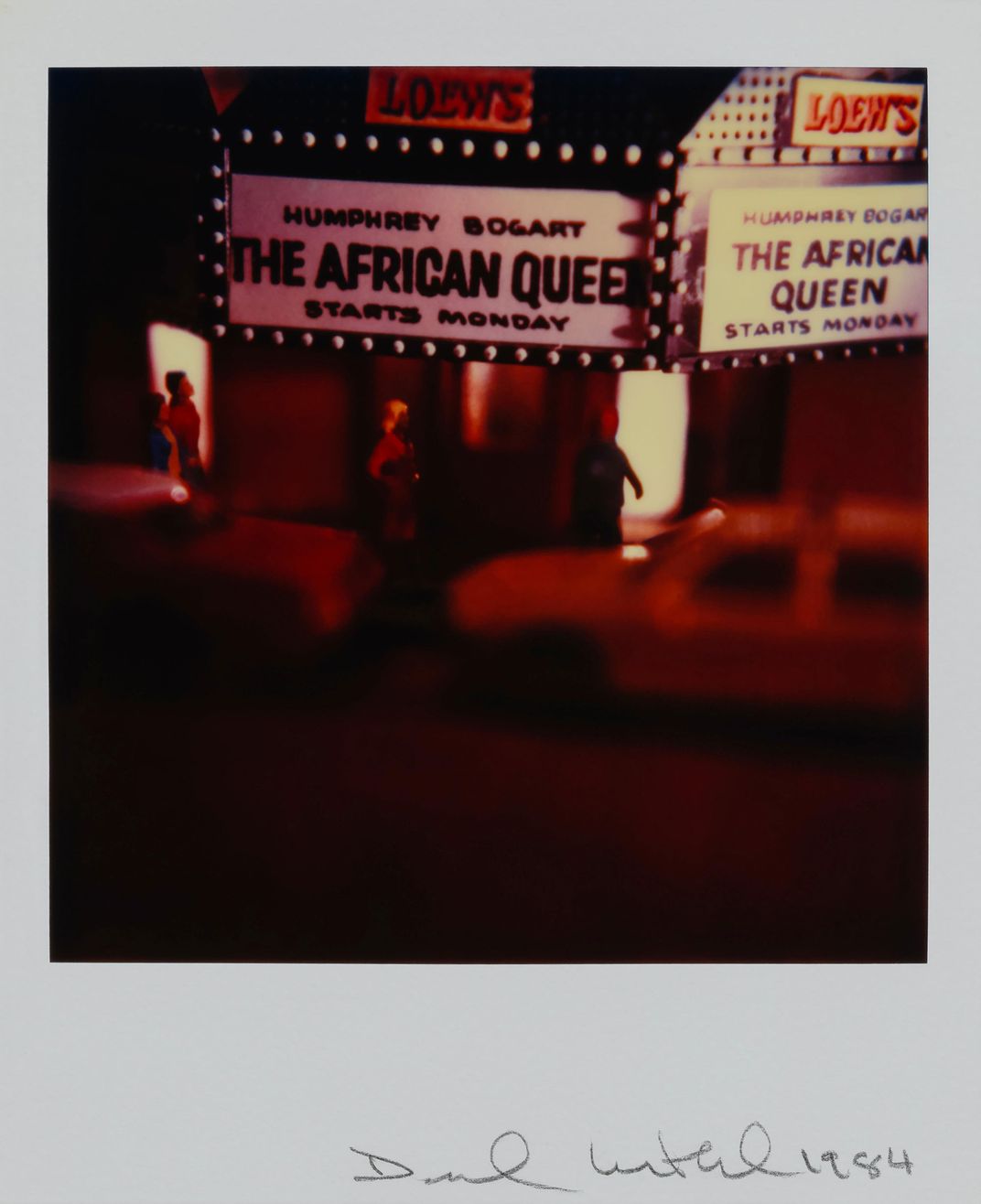

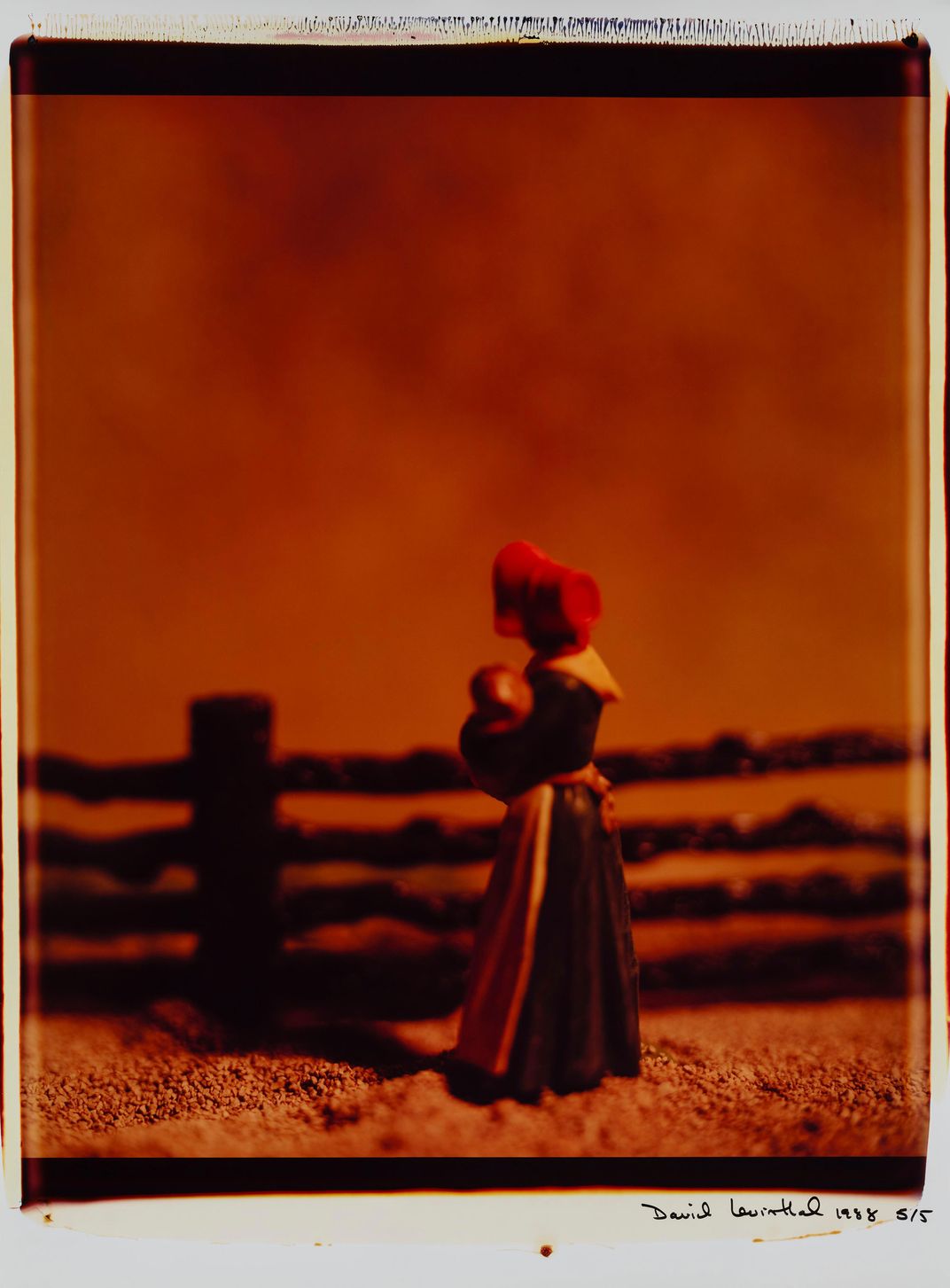

The show unites 74 color photographs taken by Levinthal between 1984 and 2018. Some belong to his “History” series, which restages such well-known events as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and George A. Custer’s last stand at the Battle of Little Bighorn, while others are extracted from the series “Modern Romance,” “American Beauties,” “Barbie,” “Wild West” and “Baseball.” All center on toys, precisely posed to serve as society's stand-ins.

By drawing on “universally recognizable” events, objects and figures, says exhibition curator Joanna Marsh, Levinthal invites viewers to bring their “own associations and memories” to photographed subjects, whether they are soldiers crossing “No Man’s Land” on World War I’s Western Front, a pioneer woman cradling her child, or a baseball player sliding into home base.

Moments in every culture become “mythologized over time. . . through the collective remembrance of an event and the retelling of that event by a community or a larger society,” says Marsh, who serves as the museum’s deputy education chair, head of interpretation and audience research.

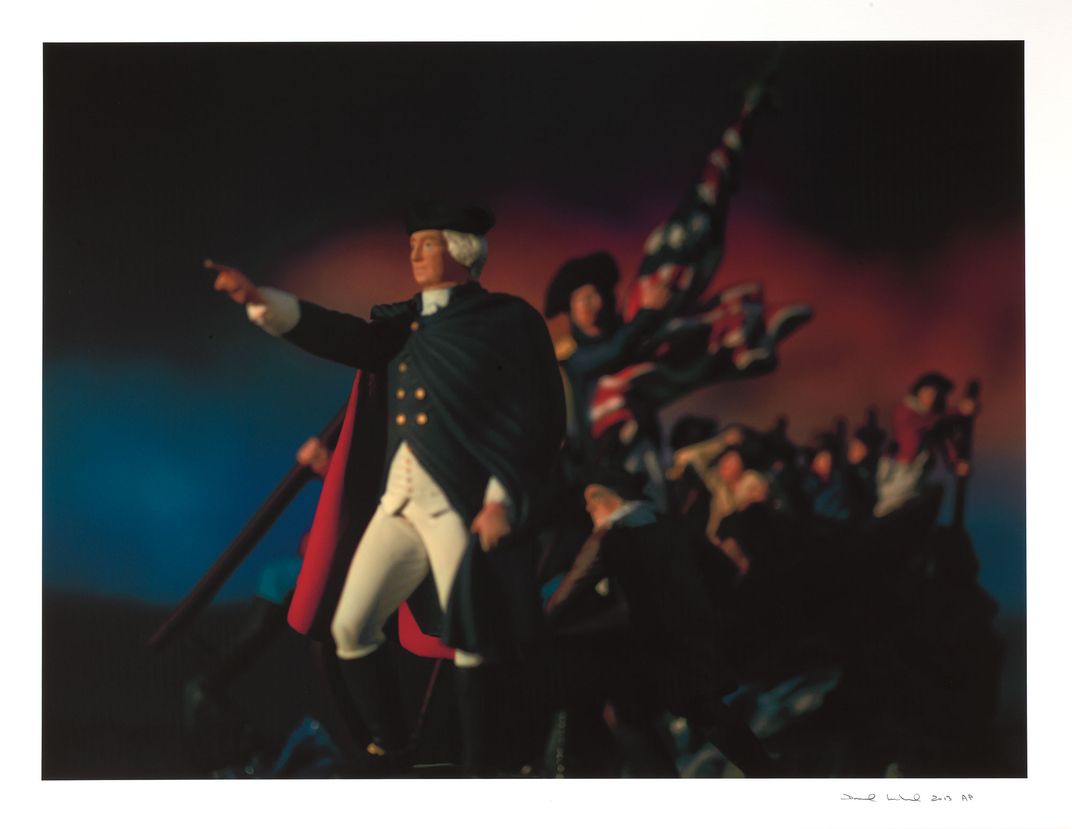

In many instances, perceptions of events are shaped by photographs, paintings or images otherwise circulated for mass consumption. George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware, for example, is cemented in popular imagination by Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 oil painting, a heroic and largely romanticized depiction of the 1776 event that was painted decades after the fact.

Levinthal’s version is similarly idealistic, portraying Washington’s progress as unimpeded by the ice and wind that actually affected the crossing. As the artist explains, this representation is “embodied in the painting, so that’s how we view it” to this day. The work’s exhibition wall text further states: “The artificiality of the figure is immediately apparent, underscoring the fiction that lies at the heart of how Americans visualize this historic event.”

Photography, meanwhile, is often viewed as a more reliable record of reality, purportedly displaying what Levinthal calls “the truth of the moment.” But just as paintings are shaped by their artist’s point-of-view, photographs are susceptible to manipulation—a fact accentuated by Levinthal’s scenarios, which are constructed wholly for the camera.

The artist’s first monograph, co-authored by Garry Trudeau of “Doonesbury” fame, exemplifies this tension between fantasy and fidelity. Titled Hitler Moves East: A Graphic Chronicle, 1941-43, the 1977 book takes a journalistic approach to the Nazis’ eastward advance, placing plastic toy soldiers in sepia-toned, manufactured yet eerily realistic war zones. The artistic nature of this early series is so subtle, in fact, that a woman came up to Levinthal shortly after the work’s publication and commented, “You look awfully young to have taken these pictures during World War II.”

Around the same time as this encounter, Levinthal stopped by a bookstore and found Hitler Moves East in the history rather than art section.

“It never crossed their mind that it was an art book, which it’s now considered to be,” he says.

As Marsh observes, many of the photographs included in “American Myth & Memory” are surprisingly sparse. Dallas 1963, for instance, focuses on an innocuous black car; in conjunction with the work’s title, however, the pink-suited figure in the backseat of the vehicle readily identifies the image’s subjects as Jackie and John F. Kennedy.

“When we look at that photograph, which is quite spare in its detail and very blurred,” Marsh says, “we see far more than what's actually in the photograph because we're bringing all those visual cues and associations that we have stored in our own memory.”

Some of Levinthal’s snapshots feature little beyond loose toys, a sandy landscape and a dark or spray-painted background. Others zoom in on aspects of complex dioramas—including one commissioned for the artist’s “Wagon Train” series and now installed in the exhibition. Visitors standing at one end of the migratory scene can peek through the glass case and simultaneously spot both a miniature mounted cowboy and, on the wall behind the diorama, a photograph of that same figure and his trusted steed.

For the majority of his more than 40-year career, Levinthal relied on Polaroid technology to bring his constructed scenes to life. Then, in 2008, Polaroid stopped producing the film used in its 20x24 camera, forcing the artist to make his first foray into the world of digital photography.

“I.E.D.,” a 2008 series on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, was the first of Levinthal’s work to receive the digital treatment. As Marsh notes, the timing was apt: Unlike Hitler Moves East, the conflict in question was ongoing and being relayed to the public via social media, 24-hour news coverage and other instantaneous sources of information. Digital technology, therefore, not only afforded Levinthal what he describes as “total freedom of scale” and a “beautiful” working system, but also provided a medium that Marsh says “felt more appropriate to the moment.”

Mass media and the influence of memory on myth-making are central concerns throughout Levinthal’s work. As the artist once explained, his “Wild West” series represents “a West that never was, but always will be,” reflecting romanticized conceptions of cowboy culture created by television and radio shows rather than the harsh reality evident in historical accounts.

Levinthal, born in San Francisco in 1949, grew up watching Westerns. While conducting research for the “Wild West” series, however, he realized the gunslinging cowboys of his imagination “bore absolutely no relationship” to the actual westward expansion of the late 19th century. Instead of offering accurate historical perspectives, Levinthal says, depictions of the period often strive to “embellish and expand” on the legend of the Wild West.

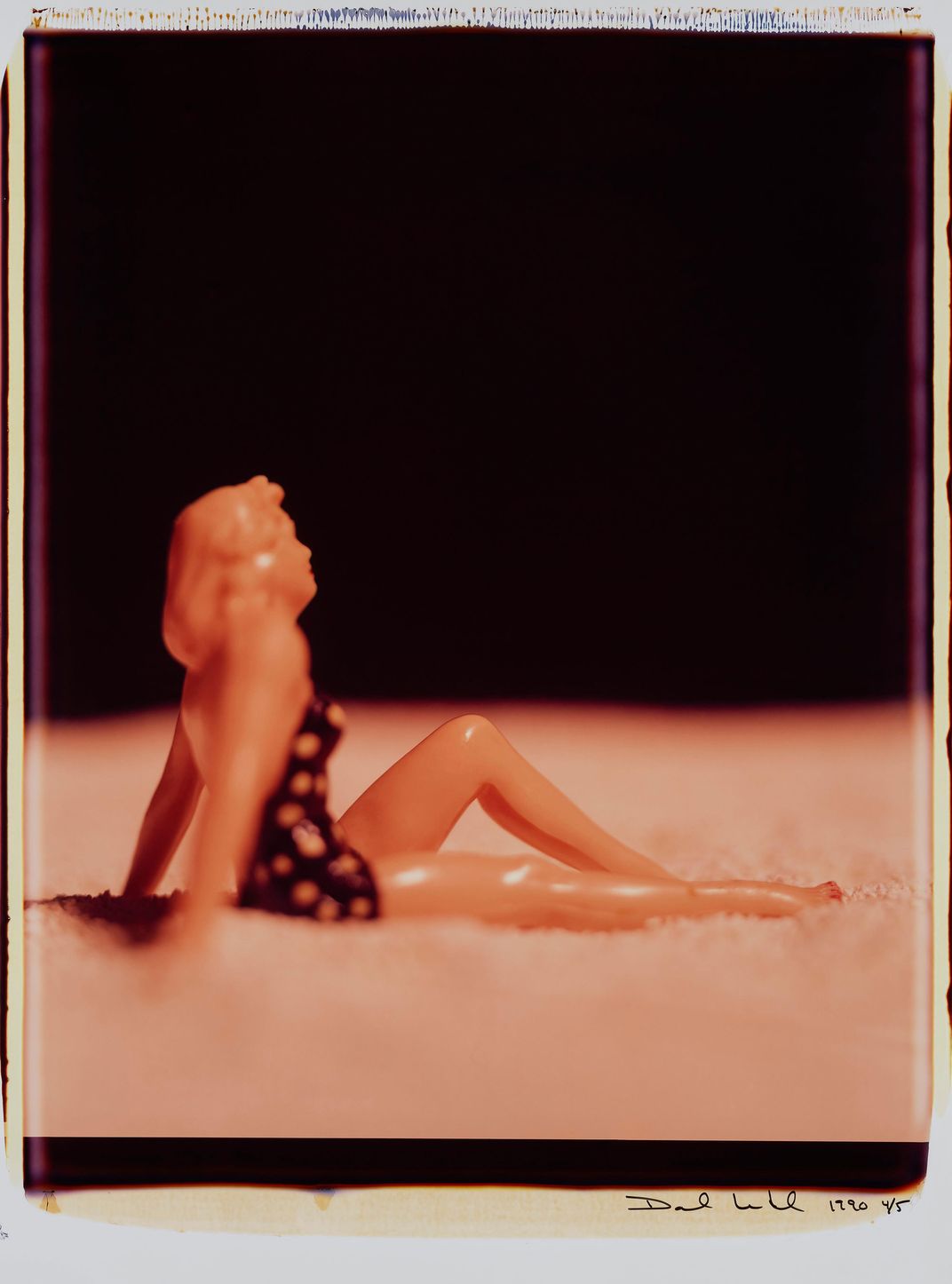

This emphasis on perpetuating fictions rather than replicating reality is also at the heart of the artist’s “American Beauties” and “Barbie” series. Both bodies of work center on idealized versions of women who alternately evince wholesome, barely concealed sensuality and fashionable domestic refinement. “The doll becomes sort of the perfection of our visual fantasy,” Levinthal says. “The doll is seemingly without flaws.”

Marsh argues that the series’ portrayal of idealized women underscores the role of toys, and particularly dolls, in teaching societal norms, values and assumptions from a very young age.

“They aren't just playthings,” the curator says. “They have a much weightier significance within popular culture.”

Ultimately, Levinthal’s work thrives on the tension between a number of seemingly discordant ideas: the innocence of toys versus the brutality of war, the veracity of photography versus the manipulation apparent in constructed scenes, and the memories of events versus nostalgic, mythologized narratives. As the exhibition wall text points out, the artist’s images hide “the toy-ness of his subjects,” blurring figures until they appear almost human, but the “illusion is never quite complete.”

To look at a Levinthal photograph is to acknowledge its artificiality and—in doing so—gain a deeper understanding of the flawed, often fictitious forces that continue to shape modern American identity.

“American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs” remains on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through October 14, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/06/b3067640-8eb9-43ff-a748-c00505861acc/iwo_jima_from_the_series_history.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)