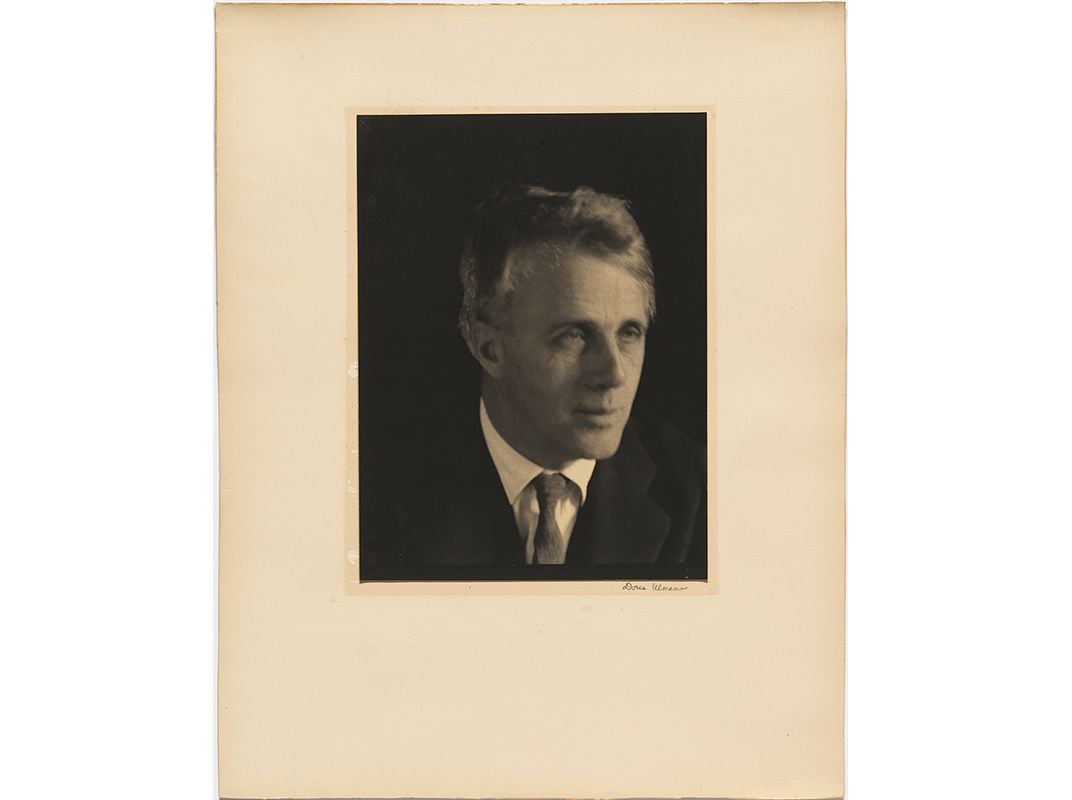

What Gives Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” Its Power?

A Smithsonian poet examines its message and how it encapsulates what its author was all about

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/67/9067f9b3-6091-45f2-b2bc-bdf5112386d4/rf_clara-sipprell-web-resize.jpg)

It’s a small irony in the career of Robert Frost that this most New England of poets published his first two books of poetry during the short period when he was living in Old England. Frost was very careful about how he managed the start of his career, wanting to make the strongest debut possible, and he diligently assembled the strongest lineup of poems possible for his books A Boy’s Will and North of Boston. Frost had gone to England to add further polish to his writing skills and to make valuable contacts with the leading figures in Anglo-American literature, especially English writer Edward Thomas and expatriate American Ezra Pound; Pound would be a crucial early supporter of Frost.

While reviews of the first book, A Boy’s Will, were generally favorable, but mixed, when it was published in 1913, North of Boston was immediately recognized as the work of a major poet. Frost’s career was as well-launched as he could have hoped, and when he returned to the United States in early 1915, he had an American publisher and a dawning fame as his work appeared before the general public in journals like The New Republic and The Atlantic Monthly.

The years in England were crucial to Frost, but they have also caused confusion in straightening out his publishing history – the books appeared in reverse order in America and the poems that appeared in the magazines had in fact already appeared in print, albeit in England. What mattered to Frost was that his English trip had worked. 1915 became the year in which he became recognized as America’s quintessential poet; in August, the Atlantic Monthly published what is perhaps Frost’s most well-known work, “The Road Not Taken.”

In North of Boston, Frost establishes himself as a close and careful observer of man in the natural world. The wonderful title evokes the rural hinterland of New England, away from the Boston society and economy. It is a region of isolated farms and lonely roads, and it is in writing about that landscape that Frost merges the traditional with the modern to become a writer who is simultaneously terrifying and comfortable. Frost’s technique is to take a familiar, even homey scene – describing a wall, birch trees, two roads – and then undermine or fracture the sense of comfort that those scenes evoke by exposing the capriciousness of modern life. Frost always draws you in, and then reveals that where you are isn’t at all what you expected.

“The Road Not Taken”, which was collected in Mountain Interval (1916), seems to be a fairly simple homily about making choices:

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler ...”

The roads divide, but the self cannot be divided so the poet has to choose. Working through the problem of choice, by the end of the poem he makes his choice in a famous statement of flinty individualism, the very characteristics said to define the New Englander and Frost himself:

“I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

The decision again plays off against the title North of Boston as an apparent declaration of independence against cosmopolitanism, society and the opinion of others. Since everyone wants to consider themselves self-reliant and unique – we don’t follow fashion or the crowd, no sir – the conclusion of the poem taps into and appeals to our self-regard.

Yet when you read through the description of the roads after Frost has set out the problem in the opening stanza about having to make a choice, one realizes that neither road is “less travelled by.” The poet/traveler looks at one “as far as I could/To where it bent in the undergrowth;” and doesn’t go that way but instead:

"Then took the other, as just as fair

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black."

Again there is confusion about the condition of the roads. The traveler/poet avoids the one that disappears in the (slightly ominous) underbrush, but then describes the one that he does take as “just as fair” as the one he rejects. And then it becomes clear the neither road has been travelled much at all. In fact, do the roads even exist at all? It appears they don’t.

Frost’s gently presented point is not just that we are self-reliant or independent, but truly alone in the world. No one has cut a path through the woods. We are following no one. We have to choose, and most terrifyingly, the choice may not actually matter. One way is as good as the other and while we can console ourselves with wishful thinking – “I kept the first for another day!” – the poet knows that there’s no turning back to start over: “Yet knowing how way leads on to way/I doubted if I should ever come back.”

The conditional tense doesn’t really apply here although Frost uses it to maintain the tone of regretfulness and nostalgia. Frost knows, as the reader gradually intuits, that you won’t go back because you can’t. The determinism of a choice, way leading on to way, in a string of events that becomes a life is unescapable. Frost’s popular appeal is all here in the layers of the poem, from the deceptively simple (yet masterfully rhyming) iambic lines to the evocation of mild regret of having made a seemingly innocuous choice. And then, the existential rug is pulled out from under your comfortably situated feet with the revelation that you have to make your own road – and it may not be of your choosing.

It’s the last stanza, though, that makes Frost into a genius, both poetically but also in his insight into human character, story telling and literature. The stanza is retrospective as the traveler/poet looks back on his decision – “ages and ages hence” – and comments how we create a life through the poetic fictions that we create about it to give it, and ourselves, meaning. The story that the poet will tell is that:

"Two roads diverged in a wood, and I

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference."

Notice the stuttering, repetitive “I” that Frost uses both to maintain the rhyme scheme (“I/by”) but also to suggest the traveler/poet’s uncertainty about who made the choice. The narrative drive is reestablished with the penultimate line “I took the one less traveled by,” to conclude with a satisfying resolution that ties everything in a neat biographical lesson “And that has made all the difference.” But it has made no difference at all. The difference, the life, is created in the telling, something that Frost does, of course, masterfully.

It is hard not to see the poem’s conclusion as Frost’s early commentary on his own career. The carefully crafted personae of the New England farmer, a seemingly artless concern for the doldrums of rural life, and an adherence to the traditional forms of poetry, even as those forms were breaking down under 20th-century Modernism. Frost was always rueful that he didn’t win the Nobel Prize for literature, an honor denied to him possibly because the prize committee saw him as too popular, but also too provincial and maybe even reactionary. Frost perhaps succeeded too well in his pose of the apparently artless rube sitting on that wall. But where he succeeded was in being a truly great poet who also had widely popular appeal. Frost’s poetry always engages us on several levels, from its sound to the seeming simplicity of its subject matter and to the depths that are revealed when his poems are given the close attention they deserve.

Related Reads

The Poetry of Robert Frost

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)