Kids Send Thousands of Letters to Santa Each Year. Here’s What Really Happens to Them

The United States Postal Service and volunteers have responded to North Pole holiday correspondence over the past century

:focal(1856x1484:1857x1485)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/14/0d/140dbb2b-c588-455f-941e-1d3a1a9cba4f/gettyimages-1291318744.jpg)

American life is on display in letters that begin with “Dear Santa.”

Yes, many of these letters feature kids endearingly asking for toys: Ayden from Tennessee says, “I’m 11 years old and I think I’ve been really good this year. My favorite things are dinosaurs and space.” Included in Ayden’s wish list for Santa is a “velociraptor plushie,” of course.

But keep reading and deeper messages emerge as well: Tenisha from Georgia, a mother of two, tells Santa, “My wish is to bring a smile to my children’s faces this year. The past few years have been really challenging for us, financially. If there is any way for you to bless me with a gift card at a grocery store … to buy groceries to make them a memorable holiday dinner, I would appreciate it.”

And 14-year-old Maddison from Maryland says, “Please if I can ask you to help me and my mom for the Christmas holiday. … Mom pays the bills, she’s a great mom.” Maddison kindly started this letter to Santa with “Hello, how are you?” It’s rare but sweet to see a letter writer ask Santa how he’s doing before making any wants known.

All these letters, from Ayden, Tenisha, Maddison and many, many more, are available to read online under the United States Postal Service’s Operation Santa program, which allows people to adopt and answer the letters.

Writing a letter to Santa Claus has been a deep-rooted tradition in the U.S. So, where do letters to Santa go? Prior to the establishment of the Postal Service in 1775, American children would burn their missives to Santa, believing that the ashes would rise up and reach him, Nancy Pope, longtime curator of postal history at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C., told Smithsonian magazine in 2017. (Pope, founding historian at the museum, died in 2019 at age 62.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/6d/286d40e4-8f7f-4404-b64c-c40df06cd524/remote-car-parents-cant-afford-680x999.jpg)

Today, despite the advent of more modern communications like email and texting, hundreds of thousands of children, from all over the globe, continue to send their Christmas wish lists to Santa using old-fashioned snail mail. And incredibly, many of those letters are actually answered.

To deal with the annual deluge, the Postal Service—Santa’s primary ghostwriter (aside from parents)—created Operation Santa in the early 20th century. In 2017, the service made it possible for kids to write to Santa online, at least in New York City. And now, everyone can.

Operation Santa was in full swing around 1912, and in 1914, the postmaster in Santa Claus, Indiana, also began answering letters from children, Emily Thompson, who served until 2018 as executive director of the town’s nonprofit Santa Claus Museum & Village, told Smithsonian in 2017. The museum answers letters sent to the town, as well as those from the area that are addressed to Santa or the North Pole.

The digital age has not put a damper on first-class mail received by the museum. “Our letter volume has increased over the years,” said Thompson.

In 1871, Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast created an image depicting Santa Claus at his desk piled high with letters from the parents of naughty and nice children. Writer Alex Palmer noted that Nast also popularized the notion that Santa Claus lived in the North Pole. In 1879, Nast drew an illustration of a child posting a letter to Santa.

The Nast cartoons fueled the nation’s imagination, and the Postal Service soon became the vehicle for children’s most fervent Christmas wishes. But the Postal Service wasn’t exactly equipped for the job, Pope said. At first, letters addressed to “Santa” or “The North Pole” would mostly go to the Dead Letter Office (DLO), as “they were written to someone who, spoiler alert, does not exist,” Pope said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/16/df16c06f-88ba-4f2c-be6e-bcb6b26814fb/f4m587.jpg)

The concept of a DLO—to deal with letters and packages with illegible or nonexistent addresses, no return addresses or improper postage—has existed at least since the first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin, Pope said. A handful of such offices were established in the 19th century and early 20th century, with the main DLO being in Washington, D.C. A few clerks, many of whom were women in the late 19th century, would sort through the dead letters and burn the ones that could not be returned.

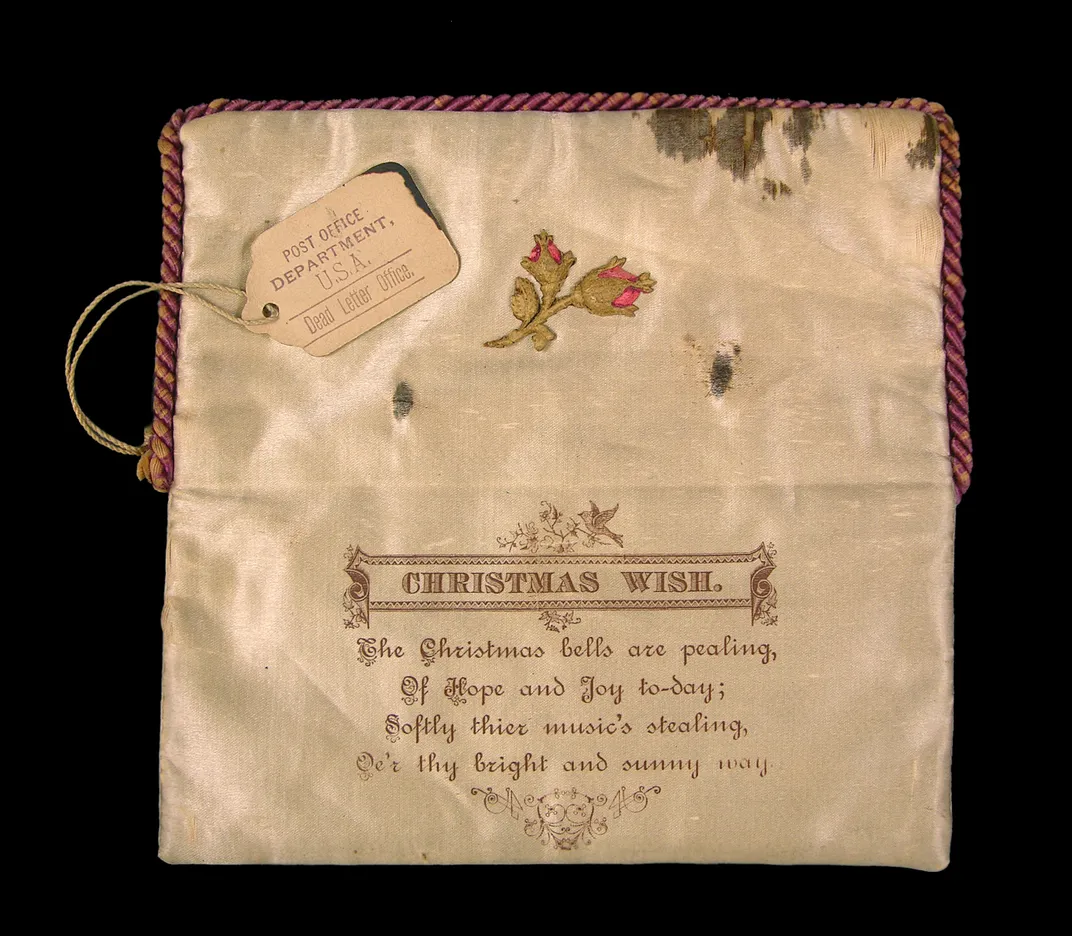

It was harder to burn packages, especially as they were often filled with interesting items, such as skulls, reptiles and even a big box of brass knuckles, said Pope. Washington’s DLO took to displaying the oddities in glass cases. Eventually the Postal Service transferred those curiosities to the Smithsonian Institution, which added them to its collections. Among those, and now in the collection of the National Postal Museum, was a soft silk pouch outlined with brocade and emblazoned with “A Christmas Greeting” in the address portion. When flipped open, the pouch revealed a similarly printed “Christmas Wish.”

“We have no clue who sent it, when, how, why, to whom—all we know is it didn’t make it,” because it was at the DLO, said Pope.

Meanwhile, the pileup of Santa letters at the DLO each year—and subsequent burning— became a source of angst. They couldn’t be delivered because they were addressed to the North Pole or to some other non-existent address. In some towns, postmasters answered the letters, which they had intercepted locally. “It was illegal for them to open the letters, but nobody was prosecuted that I know of for this,” said Pope.

In 1907, Theodore Roosevelt’s postmaster general George Von L. Meyer gave the nation’s postmasters the option to release the letters to individuals or charitable institutions to answer. But, by 1908, the Postal Service was hit by accusations that letter writers weren’t being properly vetted, leading to some perhaps ill-gotten gains. The policy was reversed, and Santa letters were again sent off to the DLO. In 1911, a new postmaster general granted unofficial permission for local post offices to again try their hand at answering Santa letters.

By 1912, Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock made it official: If the postage had been paid, individuals and charitable groups could answer letters to Santa. The program gave rise to the Santa Claus Association in New York. That group found volunteers to answer letters and deliver gifts to children. The program was a huge success, but by 1928, the founder of the association, John Gluck, was found to have scammed hundreds of thousands of dollars from its coffers, wrote Palmer, Gluck’s great-grandnephew.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/10/061072f4-21fe-4e86-80a5-9deea2d48731/18007v.jpg)

Over the decades, the Postal Service has taken steps to ensure that both letter writers and the volunteers who purchase gifts for children are not engaged in criminal or other nefarious activity. Children can now reach out to Santa in multiple ways. Parents can take their kids’ letters and mail them to an address in Anchorage—which houses a gargantuan postal processing facility designed to deal with Santa mail. That guarantees a postmark on the return letter from the North Pole.

Letters with postage and an address of the North Pole or Santa Claus are usually routed to one of the numerous regional post offices that participate in Operation Santa. Volunteers who live in the vicinity of those locations pick out a letter to answer (all personal identifying information is removed) and buy a gift for the child, which they bring to the post office. It is then delivered by the Postal Service. Thousands of other post offices participate, but postal employees only respond to letters—they don’t send gifts, said Darleen Reid-DeMeo, a Postal Service spokesperson, in 2017.

“We try our very best to get all the letters answered,” she said. “Unfortunately, because we receive so many, it’s just not possible.”

Volunteer “elves” help the Santa Claus Museum & Village in Indiana respond to thousands of letters each year, some of them mailed and some of them written onsite at the nonprofit museum. Parents or other adults can also print out templates of letters from Santa at home.

Thompson said that even though the mail volume had increased over the previous few years, the letter-writing tradition may be on its way out. In 2016, in a sign of the times, the museum began instructing volunteers to only use block letters when writing, as many children haven’t learned to read cursive, she said.

Letters allow an opportunity to tell a story, she said, noting that many children take the time to write about their days or their siblings or parents. Handwritten responses are valued by those children, too, she added, noting that today’s kids don’t receive a ton of mail.

Some commercial websites promise emails from the North Pole or video calls with Santa, perhaps hastening the demise of the old-fashioned paper response. Handwritten letters from Santa or anyone else “may become an increasingly important and rare thing,” said Thompson.

Pope agreed, noting that letter writing declined in the 1970s and 1980s, and then postcards went out of vogue: “Now we have a generation that finds email bulky,” she said. But the art has not lost its appeal for everyone. Pope noted that there’s interest among millennial women in a “rebirth of letter writing.”

Still, one thing has been constant through this evolution in correspondence: The letters to Santa keep coming.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)