For two years now, as the country has experienced Covid-19, tensions have flared alongside protests against lockdowns, masks and vaccine mandates.

The diligent strove to find a new normal in the ongoing negotiation with public health protocols to curtail infection rates. They took up social distancing and forged a greater reliance on technology to bridge the gaps between themselves and others. Others turned public discourse into a shouting match. Fueling these tensions is the sorrow that all share over the loss of nearly a million lives in the United States alone.

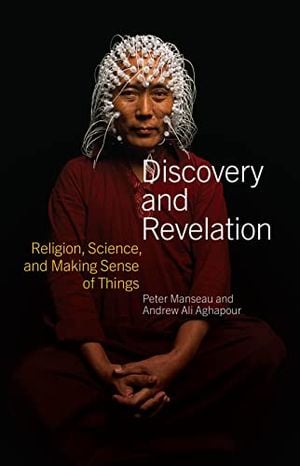

Public historians always hope their research will be seen as relevant, but we are not always prepared for the events that will make it so. I am the curator of religion at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, which is launching a new exhibition along with a book, coauthored by myself and scholar Andrew Ali Aghapour, exploring intersections of religion, science and technology—both are entitled Discovery and Revelation: Religion, Science and Making Sense of Things.

The show has been in development since 2017, but the pandemic has given some of the exhibition’s themes an unwished-for timeliness. Many of our conflicts and debates in these trying times are critically linked to the overlap of religious and scientific understandings of the world. The need to understand the history of religion in America, and how it has never been limited to what happens in homes and houses of worship, has never been more apparent.

Discovery and Revelation: Religion, Science, and Making Sense of Things

Explore the evolving relationship between religion, science, and technology in America through the centuries as humans strive to understand the world and their place in it. With at least 40 significant and rarely seen artifacts from the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, the book highlights the way religious and scientific ideas have influenced each other and informed cultural change.

This can be seen in the earliest American story explored in both the exhibition and the book. Almost exactly 300 years ago, a controversy over religion and public health ripped through Boston.

The Massachusetts minister Cotton Mather, best known for his writings on demonic possession that helped set the stage for the Salem Witch Trials in 1692, is also an important figure in the American history of science and medicine. Mather’s longing to be not just a man of God but what would now be called a man of science put him in an interesting position when a smallpox epidemic devastated New England in 1721.

To a Puritan like Mather, the cause of any catastrophe was usually clear enough. Years before, when he heard of an earthquake that destroyed the city of Port Royal in Jamaica, he believed the ground had shaken because the people of that colony had fallen into the “heathen” excitement of visiting fortune tellers. Mather likewise saw a connection between the number of miscarriages in Boston and the “great and visible decay of piety” in the city. Such hardships could be understood as the result of the wrath of God, he then believed, and so the best recourse Christians had was to atone for their sins.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/f0/2df0a719-4171-4750-b3fa-daeb18811aba/cotton-mather.jpg)

Yet when sickness hit close to home, Mather began to rethink this position. With his children suddenly showing symptoms he had seen when visiting the dying in “venomous, contagious, loathsome Chambers,” as he called the houses of the afflicted, he began to question his convictions. If God had given humans the gift of intellect, and it was possible to counteract illness through the study of these contagions, would it be wrong to fail to do so?

Eager to prove his learning equal to that of any of his peers back in England, Mather read as many European medical texts as he could lay his hands on. Emboldened by these interests, Mather proposed a radical new treatment be used to fight smallpox: inoculation. But doing so meant breaking ranks with both the Puritan elite and what then passed for common sense. The dominant religious reasoning of the time argued that if plagues were sent by God, then to work against them was blasphemy.

The controversy that followed was simultaneously the first conflict between science and religion in America and the first media-addled public health disaster.

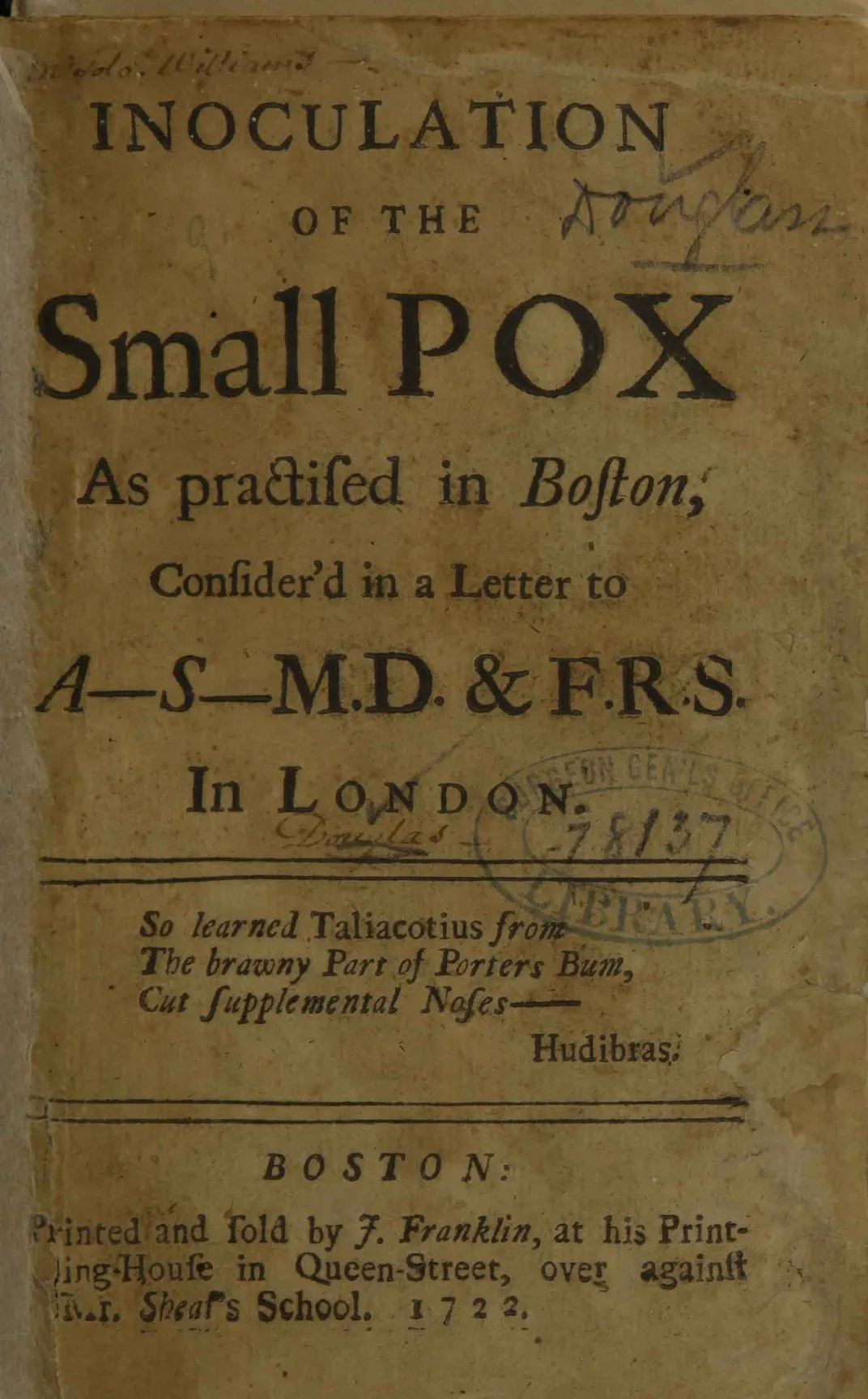

Printer James Franklin (Benjamin’s brother) fanned the flames of public sentiment by publishing screeds against inoculation generally, and Mather personally. The pamphlet war between these two factions—for inoculation and against it—played out for months.

Many of the attacks on Mather and his pro-inoculation views focused on the source of his information. For an infamous witch hunter, he was surprisingly broadminded about where he looked for new ideas. Mather had first learned of inoculation’s efficacy from Boston’s enslaved population. Many individuals had received the treatment before being kidnapped, sold and brought to America. Mather learned of inoculation from a man named Onesimus, who was enslaved by Mather himself.

In a 1716 letter to the Royal Society of London, Mather recounted that Onesimus displayed a scar on his arm and explained that he had “undergone an Operation, which had given him something of ye Small-Pox, and would forever preserve him from it.”

Mather investigated other Africans living in Boston and found that inoculation was a widespread practice. Armed with this knowledge, he began promoting inoculation as the best protection against the virus and urged Boston’s doctors to adopt the practice.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b7/8d/b78d3da2-f8c3-4c23-945a-1f9d5b759b48/untitled-1.jpg)

Skeptical Bostonians cast suspicion on Mather’s inoculation crusade, accusing him of practicing African medicine. Others raised theological objections. Rev. John Williams quoted the Bible as evidence that inoculation violated natural law: “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick,” according to Matthew 9:12.

Williams further argued that because inoculation could not be found in the Bible, it must not be the will of God.

As Mather’s opinions became known, anger at the practice became more fervent than ever. “Is it not taking God’s work out of his hands?” asked a 1721 anti-inoculation pamphlet. “Is it any better than dictating what measure of his judgement we intend to have?” demanded inoculation opponents. In other words, if inoculation worked, then God was not in control, and if God was not in control, many feared they would not have their greatest source of solace just when they needed it most.

After the effectiveness of the new practice was demonstrated through a drop in smallpox mortality following inoculation, faith in the procedure grew. Soon it became common practice to take one’s children to an inoculation hospital between smallpox outbreaks. Over the course of the 18th century, inoculation transformed in the public imagination from a potential abomination to a gift from God that humans could use to save themselves.

Fortunately, in both the 18th century and the 21st, more level heads have largely prevailed—but not before it was shown that science and religion in American life remain entwined in ways that impact us all.

Much as Mather sought to reconcile traditional religious views concerning sickness, healing and repentance with the medical advancement that came to be known as inoculation, responses to Covid-19 have included efforts to overcome religious resistance to the development of a vaccination program that promised to save countless lives.

Faith, many behind the so-called anti-vax movement allege, is the ultimate protection. One viral photograph taken at an anti-shutdown rally in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, captured this confusion of public health and personal devotion succinctly: A protester had painted the hood of his truck with the motto “Jesus is my vaccine.”

Fortunately, in both the 18th century and the 21st, more level heads have largely prevailed—but not before it was shown that science and religion in American life remain entwined in ways that impact us all.

This also has been a moment in which scientific opinion has proved divisive for some religious communities.

“Listen to the scientists” became a mantra for those who wanted to limit in-person meetings to combat infection, while “church is essential” served as a rebuttal for those who insisted the freedom of religion ought to offer exemptions to houses of worship hoping to gather their flocks.

Through it all, a variety of technologies transformed the terms of engagement between religion and science. Worship services moved online for millions. “Zoom church” became a phenomenon in its own right, with rabbis self-broadcasting sermons, Zen teachers leading remote meditation, and Gospel choirs joining each other to share hymns from the sanctuaries of their own homes.

Just as radio and television did for earlier generations of religious Americans, technology altered the terms of what it meant to come together, perhaps in ways that will continue until the pandemic becomes a distant memory.

When we try to understand why Americans, then and now, have been so quick to disagree over religion and science, we highlight what is at stake in these disagreements. Far from abstract or theoretical, the questions raised are ultimately matters of what it means to be human, what we believe our place in the universe to be, and–perhaps most crucially–what we owe to each other as members of the same vital yet frequently divided society.

One of the greatest insights offered by the study of history is that few circumstances are truly unprecedented, though that word has been used so often to describe the very recent past. When we look across time to consider earlier events that might help us make sense of the challenges we face, it is encouraging to realize how often they have been encountered and overcome.

“Discovery and Revelation: Religion, Science, and Making Sense of Things” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History through March 2023. The companion book by the same title, co-authored by Peter Manseau and Smithsonian scholar Andrew Ali Aghapour, is published by Smithsonian Books.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1500x1000:1501x1001)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/fc/12fcfb1c-5f7d-4912-8dba-17f45aba90b0/gettyimages1211474875.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)