Nearly three decades have passed since the cultural critic Mark Dery coined the term “Afrofuturism,” asking the question: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?”

To read Dery’s seminal essay “Black to the Future,” featuring conversations with sociologist Tricia Rose, fellow critic Greg Tate and science fiction writer Samuel Delany, is to learn the infrastructure on which hangs the defining characteristics of Afrofuturism that were quickly embraced by Black artists, musicians, authors and scholars.

Now unleashed across the globe, Afrofuturism’s seismic influences can be seen in fashion, music, the visual arts, technology, science fiction and perhaps most recognizably in Ryan Coogler’s 2018 blockbuster Black Panther, starring Chadwick Boseman as T’Challa in the first Marvel film to host a mostly Black cast.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/fc/99fc4df7-3987-4c9c-9d08-b7ed648cab77/ex_af03_20230315_008.jpg)

Boseman’s costume, a 3D-printed ensemble, rendered in flexible materials to artfully appear as the fictional Wakandan element “vibranium,” is now on view in the new 4,000-square-foot exhibition “Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

The show features more than a hundred objects including a wig worn by the Parliament-Funkadelic master musician George Clinton, a typewriter used by the award-winning science fiction writer Octavia Butler and the red Starfleet uniform worn by actress Nichelle Nichols in her role as Lieutenant Nyota Uhura for the Star Trek franchise. The exhibition also seeks to dig deeper into the larger intellectual understanding of Afrofuturism and its long heritage in the Black diaspora. We learn that, as Coogler puts it, Afrofuturism is “a way to bridge the cultural aspects of the ancient African traditions with the potential of the future.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1d/e0/1de0377b-4482-4a40-a95a-a3b22620c3fc/ex_af02_20230316_002.jpg)

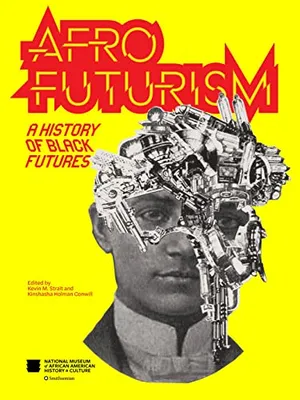

Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures

Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures comes at a time of increasing visibility for the concept, both in scholarship and in pop culture, and is a compelling ode to the revolutionary power of Black imagination.

The show’s gorgeously illustrated catalog from Smithsonian Books, edited by the museum’s curator Kevin M. Strait and deputy director emerita Kinshasha Holman Conwill, features essays from such luminaries as singer and songwriter Nona Hendryx, science fiction author N.K. Jemisin and guitarist Vernon Reid, among others. “We wanted to have a wide array of voices, and we also wanted to display the wide range of thought on the subject,” says Strait.

“I think it’s important to recognize how Afrofuturism really provides pathways for artists and others to express radical sentiment in their art and to speak about the Black experience. And it conceptualizes Black futures without constraint, in a manner that creates a space for Black content,” he adds.

The seeds for the exhibition were planted in 2011 when curatorial staff traveled to the Tallahassee, Florida, home of George Clinton to collect a replica of the iconic Parliament-Funkadelic Mothership that has since become a museum crowd-pleaser, anchoring NMAAHC’s inaugural exhibition “Musical Crossroads.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/61/6a/616a0abf-0dd8-48aa-80bc-b68890c9b358/2011_83_1_1-9_001.jpg)

Performing before screaming crowds in the 1970s, Clinton used the Mothership as a stage prop. Whizzing around the rafters overhead, it landed as part of the band’s musical storytelling, and the Mothership metaphorically and symbolically became a vehicle for the imaginary transport to a Black utopia and as an escape from the daily struggle in the face of injustice.

The exhibition follows a linear progression, finding the emergent roots of Afrofuturism in the cosmological systems of the African peoples, like the Dogon tribe of West Africa, known for their enlightened knowledge of astronomy dating back thousands of years.

“We followed the scholarship,” says Strait. “I wanted the exhibition to provide a linear approach to a very nonlinear subject by historicizing Afrofuturism and exploring its African legacies and colonial roots as we move toward 20th-century literature, music, film and visual culture.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e7/02/e702f793-d870-4d02-a0ed-e7e58e9c295d/af010103_g07221_mamma_haidara_commemorative_library_462.jpg)

The Sankofa figure, for example, a traditional artistic symbol of the Akan people of Ghana, depicting a bird with its neck turned to face backward, refers to proverbs about learning from the past or “looking back to go forward.” The word means to retrieve or to “go back and get” and lends crucial understanding to the ideas behind Afrofuturism. In a sense, Black people, whose past has been deliberately erased, are embracing Afrofuturism as a means to reconceptualize their history and a tool for speculating on a more fruitful future.

Before the term “Afrofuturism” was coined, Black intellectuals were already exploring the idea of escaping the oppressive state of Blackness by looking toward science fiction. Writer and editor W.E.B. DuBois, one of the founders of the NAACP, was an early practitioner. In the 1920s, DuBois published “The Comet,” a post-apocalyptic story about a celestial object that crashes into Earth, leaving a Black man and a white woman the sole survivors in a destroyed New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/86/0386a182-abfd-4474-92b8-23ac5e11b808/clintonwig.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/be/01be0148-4d2c-46c2-adbd-daea47e98224/art_clinton_george01_1.jpg)

Butler began publishing science fiction novels surrounding the Black experience in 1976. She is best known for her 1978 novel Kindred about a Black women who travels from 1976 to discover her enslaved relatives in the antebellum south. Her 1993 novel Parable of the Sower is speculative fiction depicting 2024 as a year plagued with climate change and social inequality. In 2020, Parable of the Sower landed at number 14 on the New York Times bestseller’s list, likely for its prophetic nature during a time when the world was experiencing a global pandemic. Her typewriter is a powerful relic of the author’s prodigious output.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/6a/606aeeb6-0b7f-4a5a-8acc-f35a31c71d6d/af0301ca01_2016_126_006.jpg)

The show’s many arresting artifacts document Afrofuturism’s wide influence across the spectrum of Black life—a flight suit worn by Space Shuttle commander Charles Bolden Jr.; actor André De Shields’ costume from his performance as the Wizard in the 1975 Broadway production of The Wiz; a mirrored casket created in 2014 by a group of artists and used in the Ferguson, Missouri, protests following the 2014 police shooting death of Michael Brown.

On Star Trek in the 1960s, Black people could watch Nichols play the role of the Swahili-speaking Lieutenant Uhura, one of the first Black women actors on primetime television. Though she was frustrated by the racism she faced at the hands of the show’s production company, Desilu, Martin Luther King Jr. encouraged her to continue to play this powerful and impactful role on one of the few shows he allowed his children to watch. The sleek red uniform she wore in the role became her signature look for the show’s three seasons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f9/82/f982918c-c98c-480f-aada-cc1c65fb2e80/2021_32_1_008_2.jpg)

Perhaps most poignant of the exhibition’s artifacts is a flight suit from the science education program Experience Aviation that once belonged to Trayvon Martin, who was fatally shot in 2012 by the vigilante gunman George Zimmerman. Martin, who was just 17 when he died, had dreams of working in aviation. “It was a badge of honor for the students to have the flight suit with the patches on it. … He loved it,” Trayvon’s father recalled.

Strait says that in the contemporary moment “there are organizations being formed around the country … centered on the concepts of Black joy, but also Black pain, dealing with generational trauma. Organizations that are activist in nature, that deal with the movement for Black lives are centered around the concept of Black futures and determining what those futures will be.”

Afrofuturism has become an influential driving force in mainstream culture. From Nichols’ role on Star Trek to the phenomenon that Black Panther has become, Afrofuturism pushes the culture forward with narratives that depict Black people in momentary instances of freedom from contemporary oppressive forces.

The ability to imagine or speculate alternative futures, ones that are drastically different from the present realities, allows Black people room for liberation and the freedom to see life differently. It might also allow people of other races and experiences to consider what life would be like in a utopian Afrofuturist world.

“Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures” is on view at the National Museum of African American History and Culture through March 24, 2024.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1500x1000:1501x1001)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a2/87/a28715d5-c6c3-48b0-abd1-153ff4c18fad/ex_af02_20230315_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/shantay.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/shantay.png)