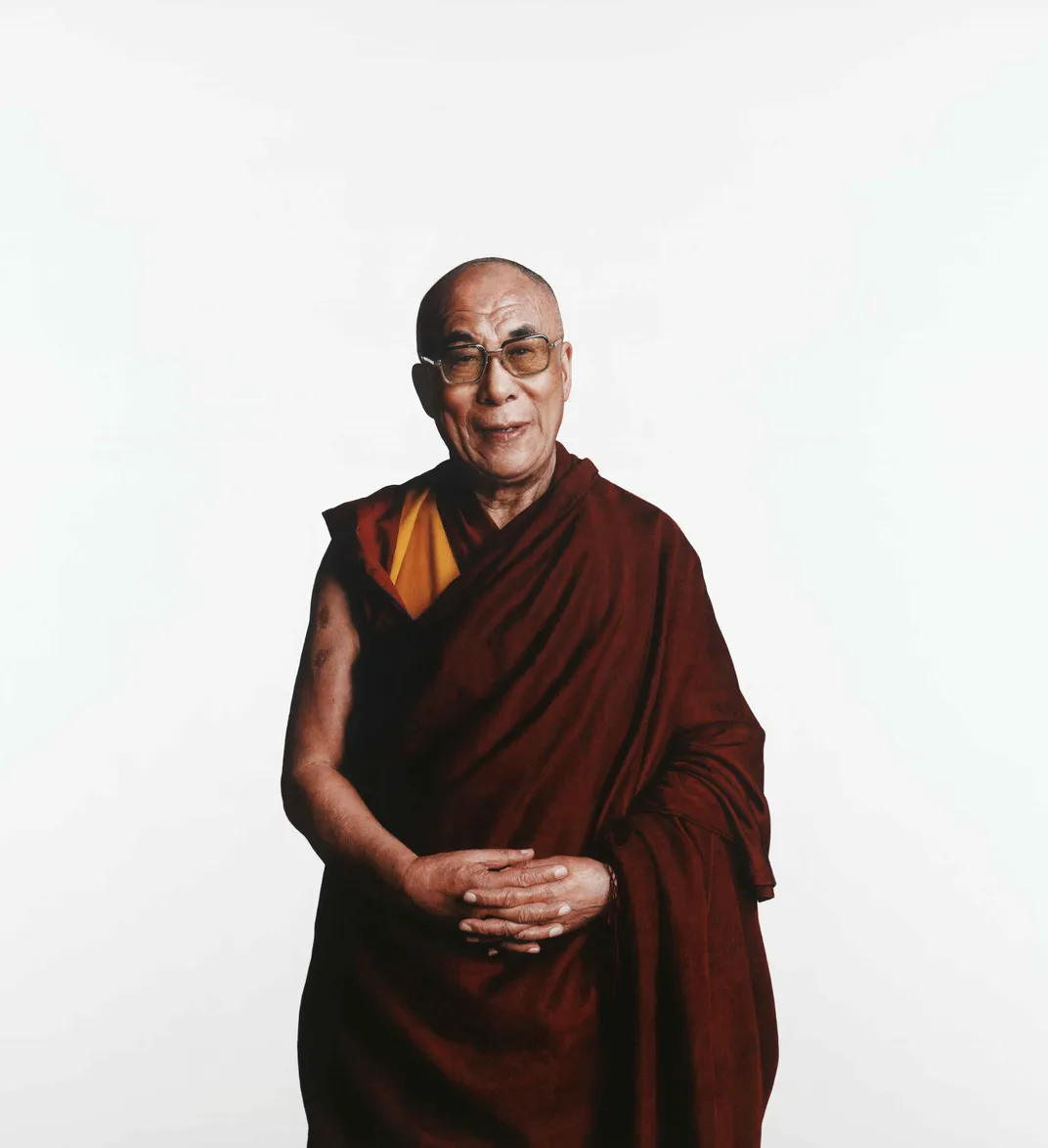

More than ten years ago, photographer and photorealist painter Robert McCurdy visited the 14th Dalai Lama—Tibet’s former spiritual and political leader—in the Chicago home of Thomas and Margot Pritzker, two of the world’s preeminent collectors of Himalayan art. McCurdy was there to take the spiritual leader’s picture, which would later be transformed into a stunning portrait. But before McCurdy could apply a single brushstroke to his canvas, he needed to get the Dalai Lama’s attention.

“I was told that if the Dalai Lama wasn’t engaged, he would just wander off,” recalls McCurdy.

Luckily, the Tibetan leader didn’t amble away. McCurdy ultimately managed to snap more than 100 pictures of the monk by the end of their session. After the artist shot every piece of film—all the color, black and white and miscellaneous rolls—the Dalai Lama wanted to take one more picture with the photographer himself.

Listen to the Portraits Podcast episode "Getting Real with Robert McCurdy"

“He wanted to do a photograph together, and I said, ‘I’ve got no more film,” says McCurdy. “He got his assistants to pull apart the house and find a camera, and they found an instamatic, so we took a picture together.”

In 2008, McCurdy finished his captivating depiction of the religious leader. In the final portrait, the Dalai Lama dons glasses and long, burgundy robes; cocks his head to one side; and folds his arms in front of his torso. His playful personality comes across in the painting. He smiles slightly at the viewer, and the warmth of his grin touches the apples of his cheeks.

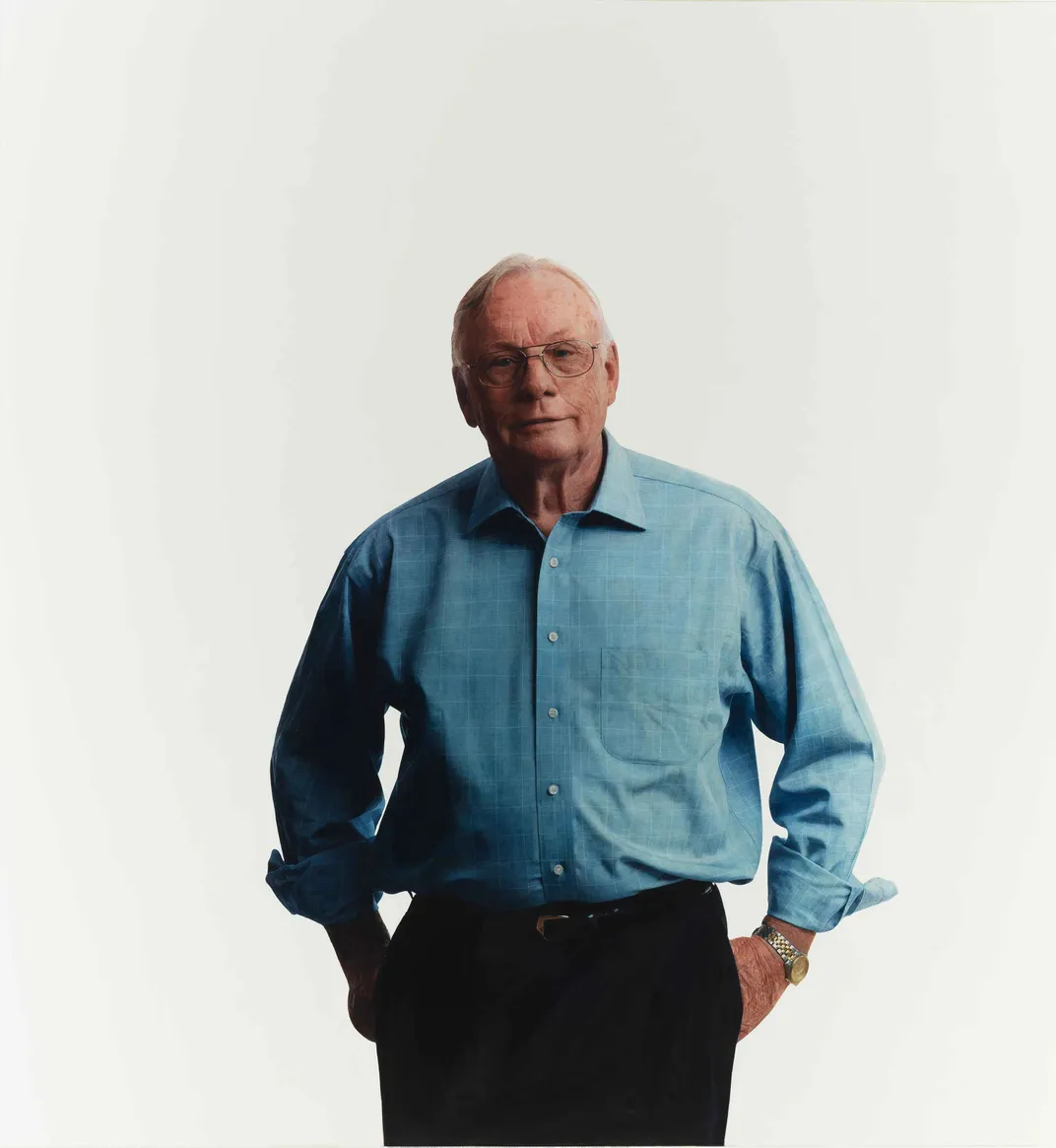

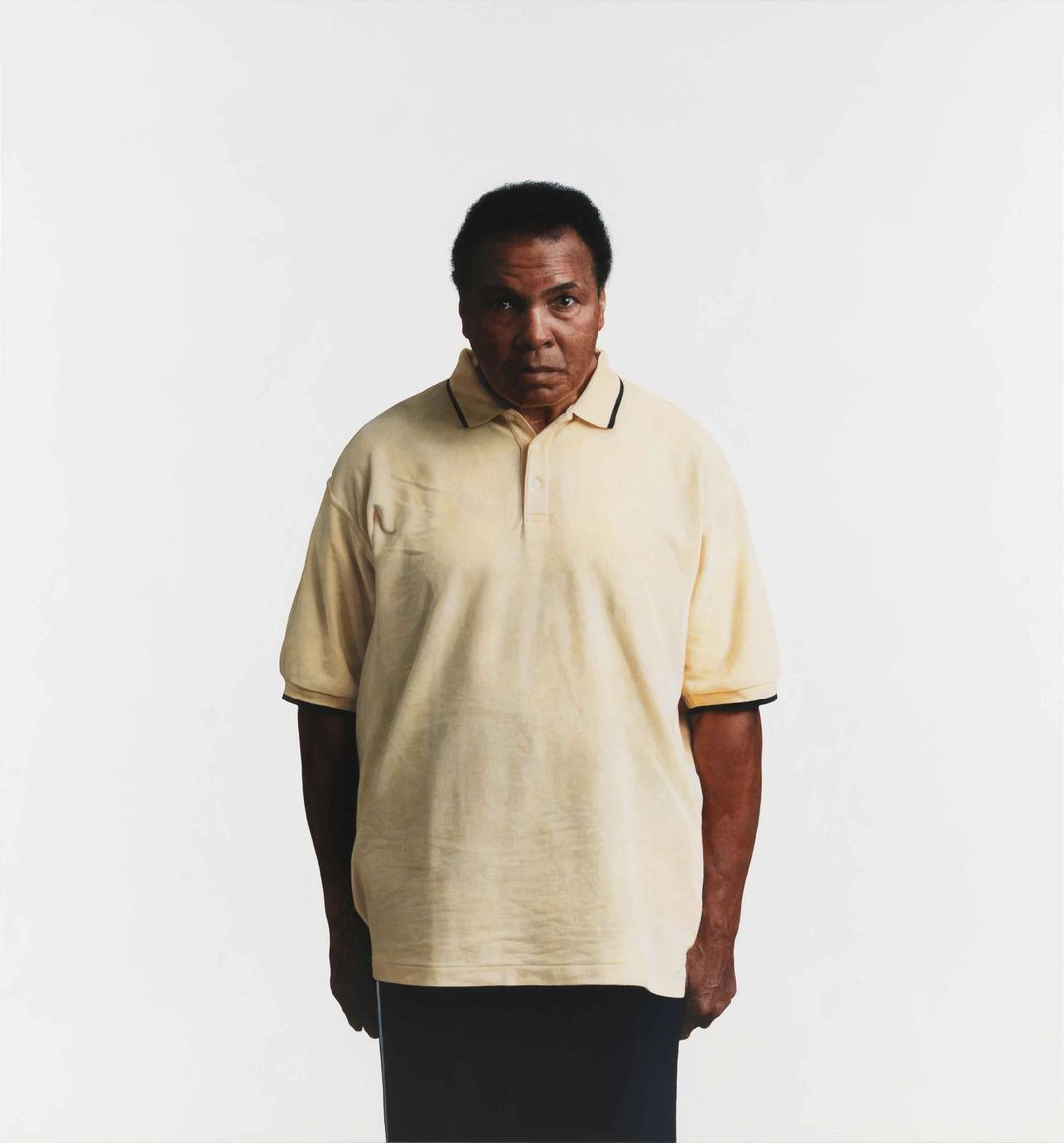

This portrait is one of many featured in an exhibition that opened last fall at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. (The museum is now closed due to Covid-19 restrictions.) Now available online, “Visionary: The Cumming Family Collection,” includes portrayals of Muhammad Ali, Neil Armstrong, Warren Buffett, Toni Morrison, Jane Goodall and others. Part two of the online exhibition debuted December 4 and includes portraits by American artists Jack Beal, Chuck Close and Nelson Shanks.

Ian McNeil Cumming (1940–2018), a noted businessman and philanthropist, and his wife, Annette Poulson Cumming, began to amass their portrait collection in 1995 and continued to build it for more than 25 years. Their friend D. Dodge Thompson—who is the chief of exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art—helped the Cummings to commission and acquire more than 24 portraits of global leaders in various disciplines, including politics, writing and business.

In his essay “Portraits of the Good and the Great: The Ian and Annette Cumming Family Collection,” published in the exhibition's catalogue, Thompson explains that McCurdy was invited to work with the Cummings in 2005 and has, “consistently and exclusively worked with them, producing on average one portrait each year.”

“[The portraits] are kind of hard to put together. [I spend] a year to a year and a half on each project,” McCurdy says, explaining why his process is so exhaustive. “So, its six or seven days a week, nine hours a day, every day. I’ve recently started taking Sundays off, which has turned out to be a good thing, but for 20 years it has been seven days a week.”

McCurdy’s portraits are so labor intensive because they are meticulously rendered. Every mark is intentional, from the baby hairs that frame his subjects’ temples to the crow’s feet that border their eyes to the scraggly hangnails that dangle from their nailbeds. The large scale of the paintings—which are about as wide as the length of McCurdy’s arms—allows viewers to see these minutiae in full effect.

“What strikes me about Robert McCurdy’s work and the photorealist aspect is the attention to detail. Even the fibers on the subject’s clothing, every line and wrinkle,” says Dorothy Moss, the museum's acting director of curatorial affairs.

However, not everyone wants to see themselves in high definition, and the prospect of looking at such precise portrayals requires trust between the painter and the painted. “When anyone sits for a portrait there’s a great deal of vulnerability involved, and there has to be a real connection between an artist and a subject that brings about a powerful portrait,” says Moss.

For the Cummings, McCurdy began with the writer Toni Morrison (1931–2019), who was the first American author to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature since John Steinbeck in 1962. Morrison was selected because the couple “admired the power of her voice and the aching rawness of her unforgettable narratives,” according to Thompson’s essay. Her oeuvre includes her 1970 debut novel, The Bluest Eye—a chronicle of the life of a young black girl desperately craving azure blue eyes—and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved from 1987—a gripping account of an escaped slave who kills her child to save her from slavery.

In a 1998 “60 Minutes” interview with Ed Bradley, Morrison explained why narratives about blackness were so central to her work: “The truth I happen to be most interested in has to do with the nature of oppression and how people survive it or don’t. It’s amazing to me, just particularly for African Americans, that we’re not all dead.”

Morrison’s portrait is monochrome. Her salt and pepper hair sits atop an ash-gray cardigan, which is only fastened by its topmost black button, and she wears a charcoal shirt beneath her sweater. Deep folds run from her nostrils to the corners of her lips, which are pursed in an even line. Her face is as blank as the white wall behind her.

“She’s got an absolutely no-nonsense kind of expression,” McCurdy tells curator Kim Sajet in the museum’s Portraits podcast “Getting Real with Robert McCurdy.”

Though McCurdy has painted a number of distinguished individuals, his portraits all have one thing in common. Each of his pieces focus on the gaze—an active relationship between the object and the viewer. This is reflected in many of McCurdy’s stylistic choices. His subjects are all placed against a stark, bleached background, and most of their faces are devoid of expression.

“So, once it was established this was what we were going for […] anything that didn’t achieve those ends had to go,” says McCurdy. “Backgrounds were out. Time’s out. Story’s out. Everything’s out except for this moment because everything else just distracts from the idea of letting the viewer establish meaning.”

While this lack of context might make some artworks appear stoic—unfinished, even—McCurdy’s subjects manage to draw the viewer into an unspoken conversation between themselves and the painting.

“There’s nothing cold about his work. Even though they are set in these kinds of empty spaces, when you are able to come up close in person and look. It’s astonishing,” says Moss. “To me, that separates it from a photograph because you don’t necessarily see that much detail in a photograph all at once. And we do have people come in who think that they’re looking at a photograph, and then they get kind of confused. His work stops people in their tracks.”

McCurdy achieves this effect by taking pictures of his subjects prior to painting them, which gives him the ability to paint hyper-specific features with startling accuracy. He initially shot his subjects with a Sinar P2 large-format view camera, sometimes using more than 100 sheets of film in a single setting. Now, he shoots reference photos with a “ridiculously gargantuan digital camera.”

“Photography very beautifully slices time. We’re trying to extend it,” says McCurdy.

Much like Morrison, Nelson Mandela sought to speak to the realities of marginalized people. In 1944, Mandela joined the African National Congress (ANC), a black liberation movement, and engaged in activism against apartheid, the country’s state-sanctioned racial segregation policy. He continued to fight for racial equality, even leaving South Africa illegally to encourage others to join the liberation movement. However, Mandela’s good deeds came at a price. On June 11, 1964, he was sentenced to life in prison and incarcerated for 27 years.

“I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities,” Mandela said during his trial. “It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

After his release from prison in 1990, the black nationalist worked with the former South African president F.W. de Klerk to end the country’s apartheid system and replace it with a more democratic, inclusive government.

“The struggle against racial oppression is worldwide. It’s not only confined to South Africa,” Mandela said in a 1990 PBS interview with Robert MacNeil. “The significant political developments that have taken place today are the result of cumulative factors of internal, mass struggle and international pressure.”

Mandela’s accomplishments did not go overlooked—in 1993, he won the Nobel Peace Prize and from 1994 to 1999 he served as the first black president of South Africa. While in office, Mandela spearheaded a transition to a peaceful, nonracial democracy; established Truth and Reconciliation Commissions that investigated apartheid-related atrocities; and sought to improve the quality of life of the country’s black residents. For these reasons, the Cummings sought to capture Mandela’s likeness in a portrait. In March of 2007, McCurdy traveled to the Nelson Mandela Foundation in the Houghton Estate, a suburb northeast of Johannesburg, to take his picture, according to Thompson’s essay.

This resulted in a striking portrait. Mandela looks straight ahead at the viewer, his lips slightly downturned. His gray shirt seems to vibrate with intense energy, amplified by a blue and red pattern of leaf-like forms.

“The Mandela portrait took nearly 18 months [to complete] because of his patterned shirt, all the light and shadow that he had to capture. These are not rushed portraits,” says Moss. “Sometimes the clothing is what causes the longer completion times, but he’s willing to embrace whatever it is that they have worn to their sittings.”

Another portrait that took time was one of the esteemed primatologist, Jane Goodall. Like many others featured in the Cumming Family Collection, Goodall is a global leader in science. In the 1960s, Goodall began a long-term research project on chimpanzees in Tanzania, where she became the first person to discover that chimps can make tools and perform complex social behaviors.

“Chimps can do all sorts of things we thought that only we could do—like tool-making and abstraction and generalization. They can learn a language—sign language and they can use the signs,” said Goodall in a 2010 interview with the Observer. “But when you think of our intellects, even the brightest chimp looks like a very small child.”

McCurdy’s portrait of Goodall depicts the scientist with impeccable posture. She is standing up so straight that it seems like an invisible string is pulling her upwards. Goodall’s rheumy eyes meet us with an unflinching gaze, empty of any discernable emotion. And when our eyes travel down the painting—away from that piercing stare—we see her clothes. The beloved primatologist wears a fuzzy, bubblegum-pink turtleneck; black bottoms; and an elaborate sweater adorned with tiny circles, delicate flowers, and long, red stripes that run down the length of the sweater’s opening.

McCurdy recalls rendering the intricate sweater, “There are marks on there that are so tiny. It took so long to get that thing to be what it was.”

The exhibition’s “Part Two” shows a number of distinguished portraits by artists Nelson Shanks, Chuck Close and Jack Beal. One is a double portrait of President Barack Obama by Close, who took photographs of the former president with a large-format Polaroid camera and used them to create two tapestries. In one his face is serious, in the other, Obama beams at the viewer, and the warmth of his smile touches his eyes.

From the great novelist Gabriel García Márquez to the maverick financier Warren Buffett to the Apollo astronaut Neil Armstrong, those depicted in the Cumming Family Collection, “are [of] people who have made important contributions to American life, history and culture,” says Moss.

The exhibitions “Visionary: The Cumming Family Collection Parts 1 and 2” can be viewed online. The National Portrait Gallery remains closed due to Covid restrictions.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/b9/cbb9c050-bd1e-4dff-a166-c02bcffb7d39/dalai_lama_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/e6/8ee6c8ec-beb9-4069-b7df-06127c09366c/dalai_lama_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)