When America Entered the Modern Age

Obsolescence yaps at the heels of every dazzling invention, says curator Amy Henderson as she considers the birth of modernism a century ago

The International Exhibition of Modern Art opened in February 1913 Opening and cars lined up outside the entrance. Image from Wikimedia Commons

Amy Henderson, curator at the National Portrait Gallery, writes about all things pop culture. She last wrote about the sanctity of the summer blockbuster.

The Phillips Collection in Washington has a new exhibition celebrating the centennial of the ground-breaking Armory Show, and a photograph at the beginning of the exhibition caught my eye. The photo is an image of the Armory’s entrance, with a large banner announcing the “International Exhibition of Modern Art.” Cars proudly parked at curbside were quintessential symbols of Modernism in 1913. (Editor’s note: This paragraph originally stated the cars in the photo above were Model T’s. Apologies for the error.) Today, the juxtaposition of these now-antique cars and the banner trumpeting Modern Art is a jarring reminder about how obsolescence yaps at the heels of every dazzling invention.

In 1913, newness propelled America. Speed seemed to define what was new: cars, planes, and subways rushed passengers to destinations; “moving pictures” were the new rage, and Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin Florence Lawrence were inventing the new vogue for “movie stars”; the popular dance team Irene and Vernon Castle sparked a fad for social dancing, and people flocked to dance halls to master the staccato tempos of the fox trot and tango.

Life rattled with the roar of the Machine Age as mass technology hurtled people into the maelstrom of modern times. New York embodied the cult for the new, from its entertainment center along Broadway’s electrified “Great White Way” to the exclamation point proclaimed by the opening of the Woolworth Building—a skyscraper that was then the tallest building in the world. (For further reading on New York City in these years, I recommend William Leach’s Land of Desire (Vintage Books: NY, 1993.)

In the new book 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War, author Charles Emmerson quotes a French visitor’s amazed reaction at the electricity and elevated trains that made the city vibrate and crackle. Times Square was especially stunning: “Everywhere these multi-coloured lights, which sparkle and change. . . .sometimes, on top of an unlit skyscraper, the peak of which is invisible amongst the fog. . .a huge display lights up, as if suspended from the heavens, and hammers a name in electric red letters into your soul, only to dissolve as rapidly as it appeared.”

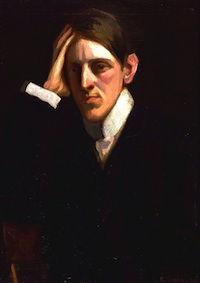

The exhibition contained significant works by such European artists as Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp, with Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase” causing the greatest controversy. Marcel Duchamp (c. 1920) by Joseph Stella. This image and all to follow are courtesy of National Portrait Gallery

Two-thirds of the 1,600 works were by American artists, including Marsden Hartley (1898) by Richard Tweedy.

The emergence of New York City as the capital of Modernism fueled the drive to proclaim America’s arrival as a cultural force as well. Movie stars like Pickford and Chaplin and Broadway composers like Irving Berlin and George M. Cohan were giving American popular culture its first international success, but European artwork was still recognized as the High Culture benchmark.

The International Exhibition of Modern Art that opened in February 1913 at the Armory meant to change all that, focusing not on the staid styles of traditional European art but on a “modern” contemporary approach. The exhibition contained significant works by such European artists as Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp, with Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase” causing the greatest controversy. This Cubist painting may have scandalized some viewers, but it also brilliantly epitomized the spirit of Modernism in its depiction of a body moving much as if it were being unspooled in a silent filmstrip.

Two-thirds of the 1,600 works were by American artists, including John Marin, Marsden Hartley, James McNeill Whistler and Mary Cassatt, and the show did mark a watershed in the recognition of American art. Former President Theodore Roosevelt reviewed the exhibition for Outlook and, while dismayed by the Cubist and Futurist works (“a lunatic fringe”), reported that the American art on view was “of the most interest in this collection.” He particularly relished that “There was not a touch of simpering, self-satisfied conventionality,” and that new directions were not obliged “to measure up or down to stereotyped and fossilized standards.” Overall, he was grateful that the exhibition “contained so much of extraordinary merit.”

To recognize this year’s centennial of the Armory Show, James Panero recently wrote in The New Criterion that the exhibition was “the event that delivered American culture, kicking and screaming, to the world stage.” It became a proclamation of America’s place in modern life, and “its most radical feature was the show itself,” which became a defining moment in the history of American art.

Along with the riot caused by Diaghilev’s dancers and Stravinsky’s music in the 1913 Paris premiere of The Rite of Spring, the Armory Show signaled the start of the 20th century. Even with the chaos of the Great War that followed, the search for the new soldiered on. Our media landscape and aesthetics today—our Facebook blogs, Tweets and Instagrams—are largely products of the Modernist belief that technology improves everyday life by connecting us. It also assumes that a century from now, the iPhone will be as antiquated as the Model T.

In addition to the Phillips Collection’s exhibition “History in the Making: 100 Years After the Armory Show” (August 1, 2013-January 5, 2014), The New-York Historical Society has organized a major exhibition called “The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution” (October 11, 2013-February 23, 2014); and the Portrait Gallery will be showcasing the Armory Show in its Early 20th Century gallery starting August 19th.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)