When It Comes To the Baby Boomers, It Is Still All About “Me”

Millennials have got nothing over the Me Generation, says cultural historian Amy Henderson after touring two new shows on Boomers and the ‘60s

Before there were “selfies,” there was Me.

Although selfies flood the current visual landscape, this social media phenomenon did not invent obsession with the self. In fact, a spotlight on the personality of the self is a defining element of American culture. Every generation is guilty of putting the “Me” in its ME-dia, and with each generation of media technology, the “Me” gets bigger.

In the late 19th century, advertisers discovered that placing images of well-known personalities on products boosted sales; magazines flew off newsstands when popular Broadway stars peered from their covers. Personality quickly became the focal point of America’s rising consumer culture. In the 1930s and '40s, Hollywood’s studio system became a landmark in the glorification of “Me.”

In neighborhood movie theaters across the nation, silver screens projected celluloid icons that were larger-than-life. The glamour studio, MGM, proclaimed its acting stable included “more stars than there are in the heavens.” Ego was essential to the star personality, and the studios went to extraordinary lengths to nurture a grand scale of star narcissism. Between 1989 and 1994, I conducted a number of interviews with one of the biggest stars of that era, Katharine Hepburn. I remember how she wagged her finger at me and said: “I was a movie star from my first days in Hollywood!” She called her 1991 memoir Me.

With the break-up of the studio system after World War II, the “self” had to find a new starship. The population explosion that began in 1946 and, according to the United States Census, extended until 1964, produced a generation of “Baby Boomers” who merrily embraced their selfhood. Hollywood cinema had helped to shape the idea of “Me,” for adolescents of the great depression, who would grow up to became World War II’s “Greatest Generation.” But it was television that branded the coming-of-age for the Boomers. TV was an immediate communicator, broadcasting events instantly to living rooms across the nation. Boomers learned the transformative power of change from their sofas, and the immediacy of television instilled a lasting sense of personal connection to the techtonic cultural changes that were “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Writing in 1976, journalist Tom Wolfe described Boomers as creating a “Me Generation” that was rooted in postwar prosperity. Good times created “the luxury of the self,” and Boomers happily involved themselves with “remaking, remodeling, elevating, and polishing one’s very self … and observing, studying, and doting on it (Me!)” Their mantra was, “Let’s talk about Me!”

TIME Magazine has chronicled the attention-adoring Boomer Generation from the start, beginning with a February 1948 article that described the postwar population burst as a “Baby Boom.” Twenty years after the boom began, TIME’s “Man of the Year” featured the generation “25 and Under.” When the Boomers hit 40, TIME wrote about “Growing Pains at 40.”

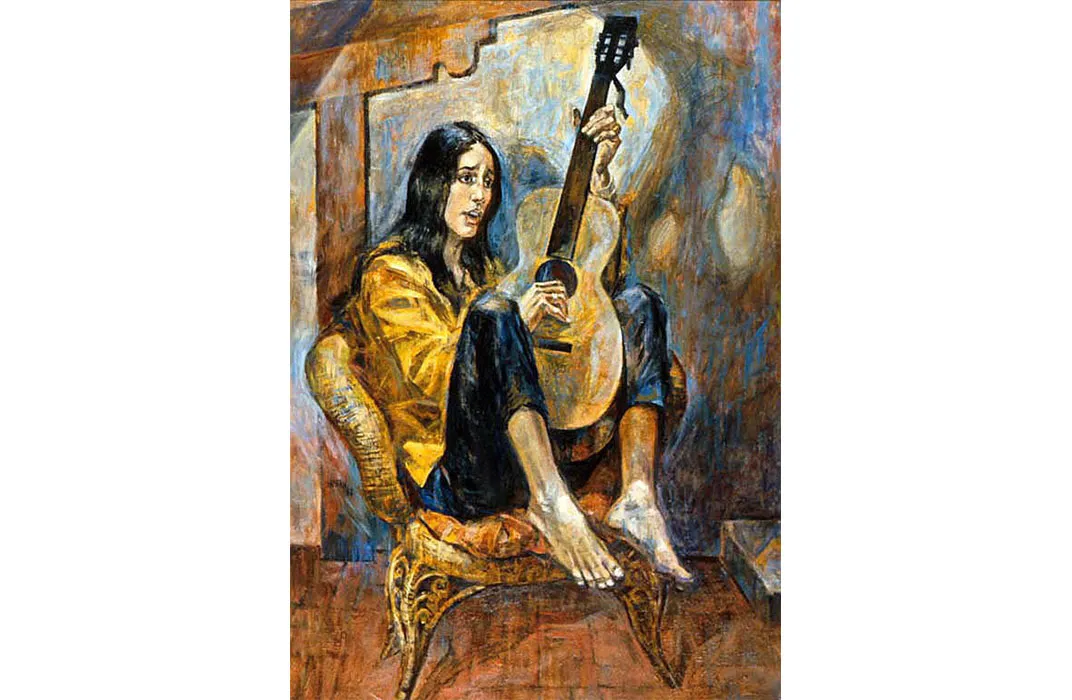

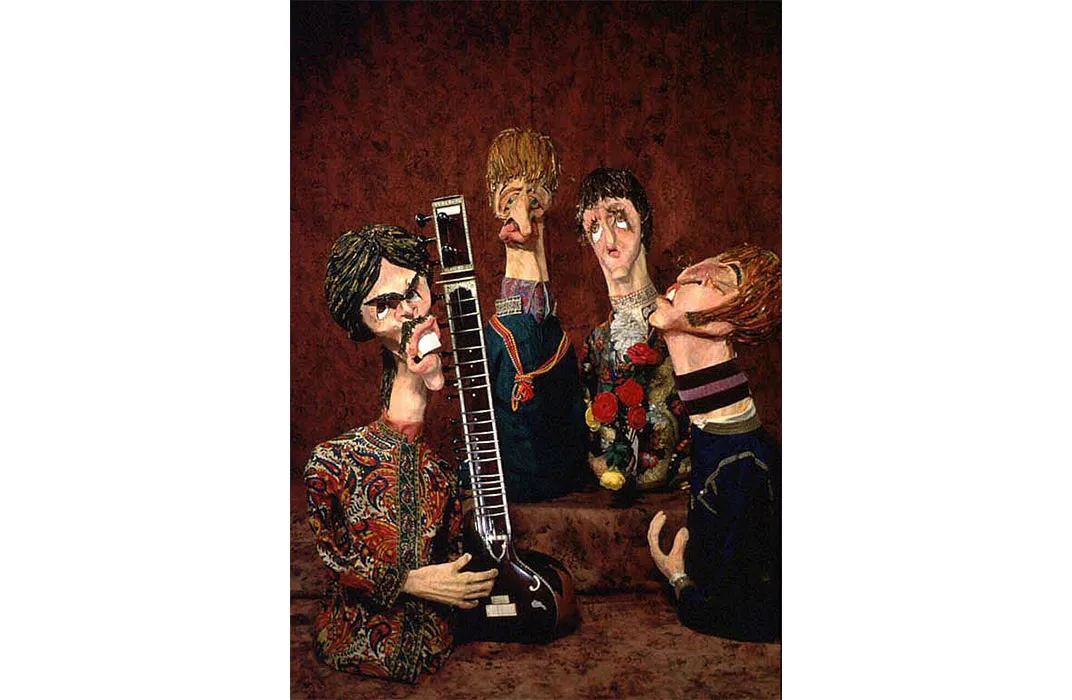

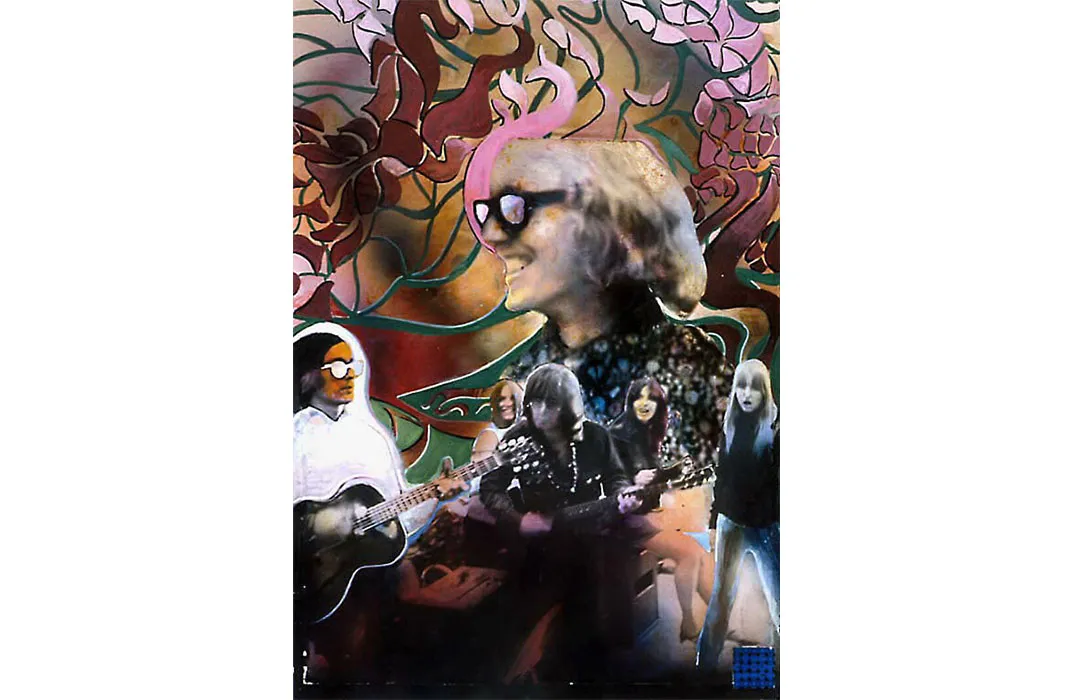

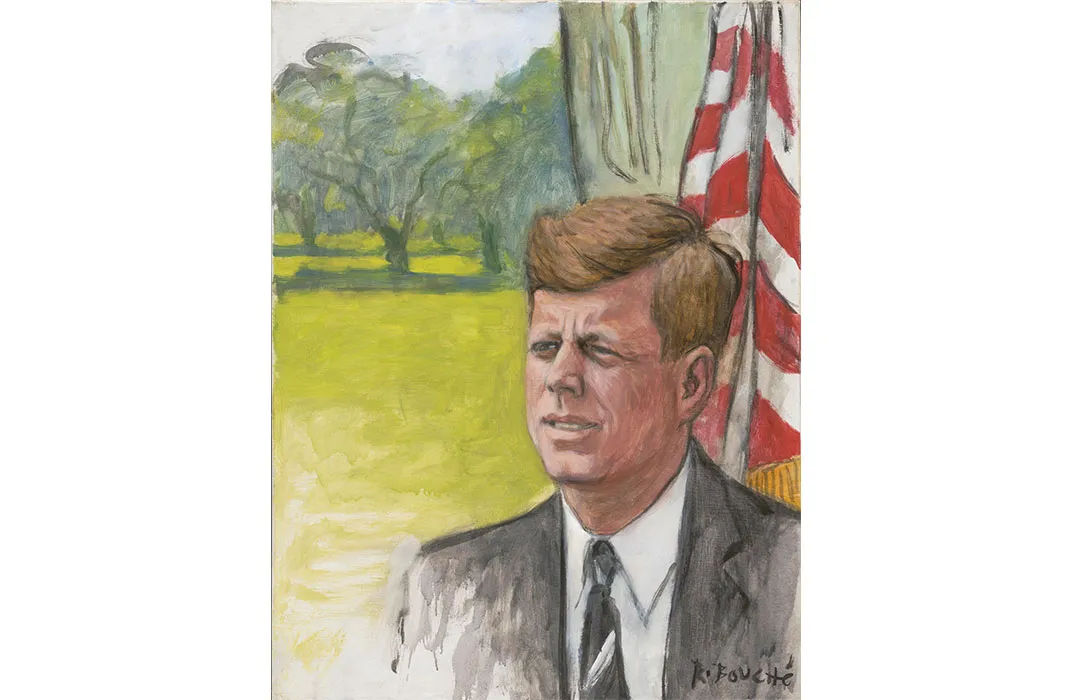

Recently, the National Portrait Gallery opened an exhibition entitled “TIME Covers the Sixties,” showcasing how the publication spotlighted the Boomers in their defining decade. The issues that defined the Boomers gaze out from such TIME covers as the escalation of the war in Vietnam; Gerald Scarfe’s evocative sculpture of the Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper heyday; Bonnie and Clyde representing “The New Cinema;" Roy Lichtenstein’s deadly-aimed-depiction of “The Gun in America;" and finally, Neil Armstrong standing on the moon.

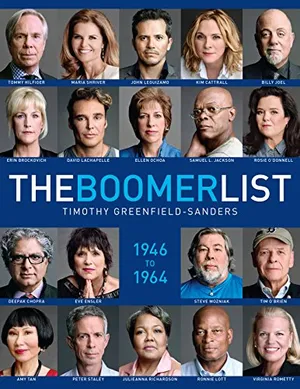

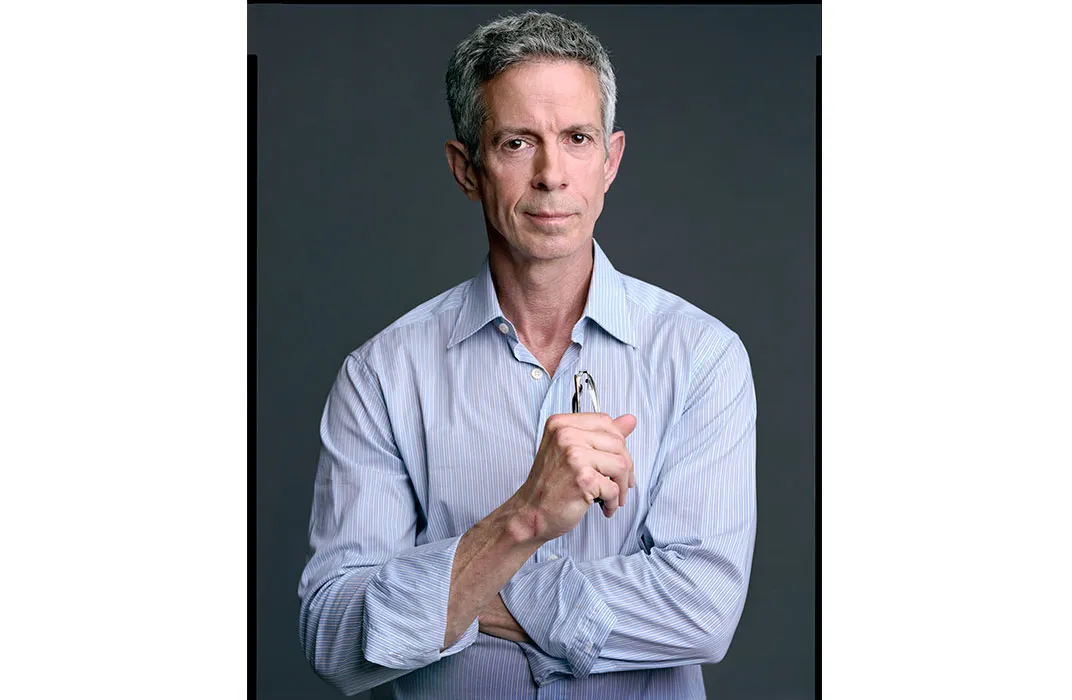

A broader generational swath is celebrated in Timothy Greenfield-Sanders' new exhibition, “The Boomer List,” now on view at the Newseum. The exhibition was organized when the American Association of Retired Persons, AARP, commissioned Greenfield-Sanders to document the Baby Boomers, the youngest of whom are turning 50 in 2014. Greenfield-Sanders has curated such well-received exhibitions as the 2012 show, “The Black List” at the Portrait Gallery, and he agreed that it would be fascinating to focus on the Boomer “legacy.”

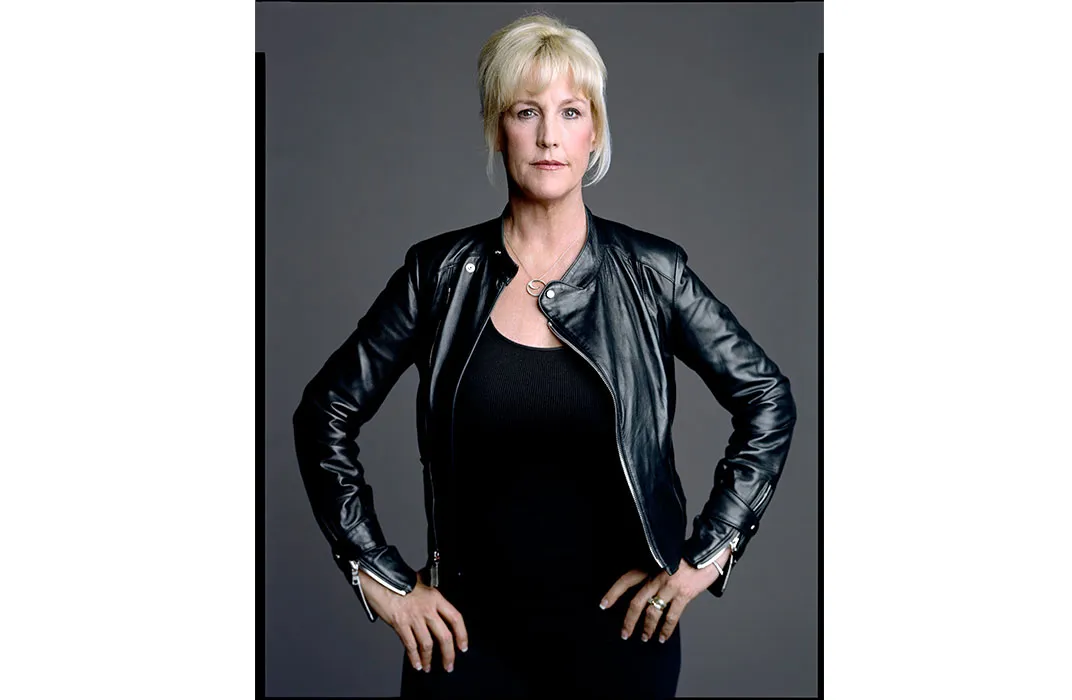

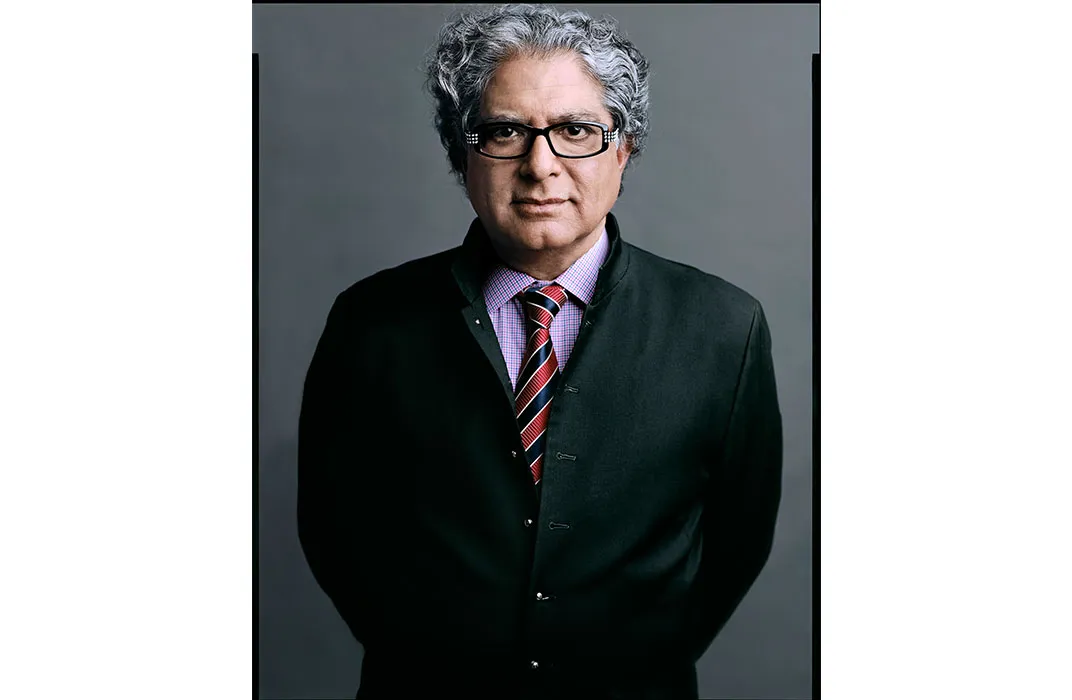

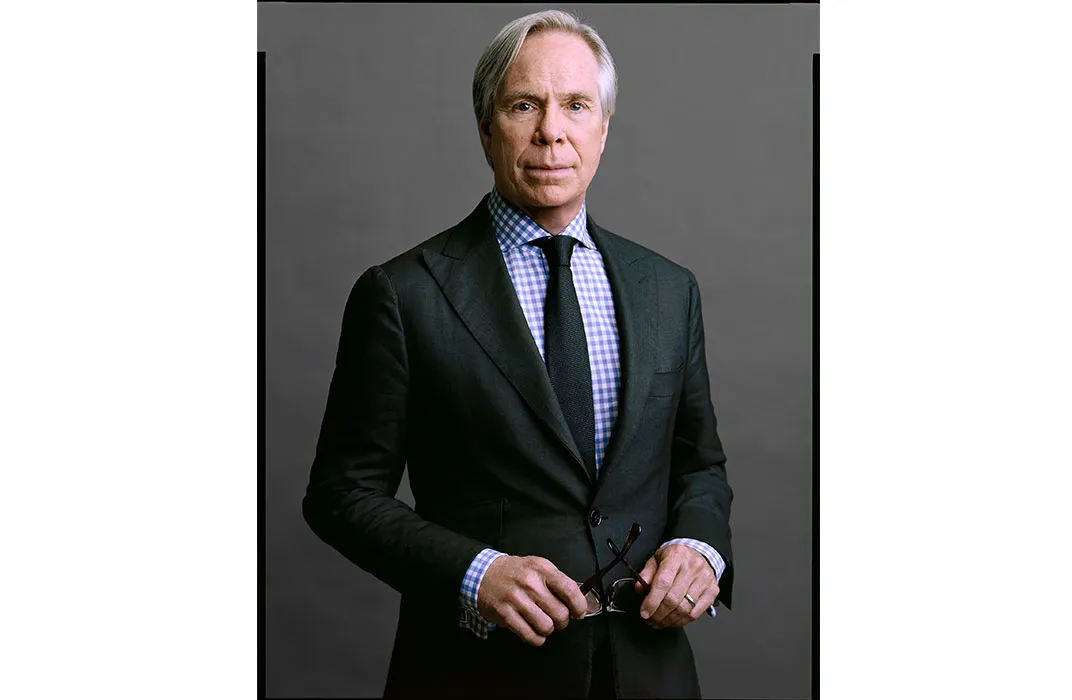

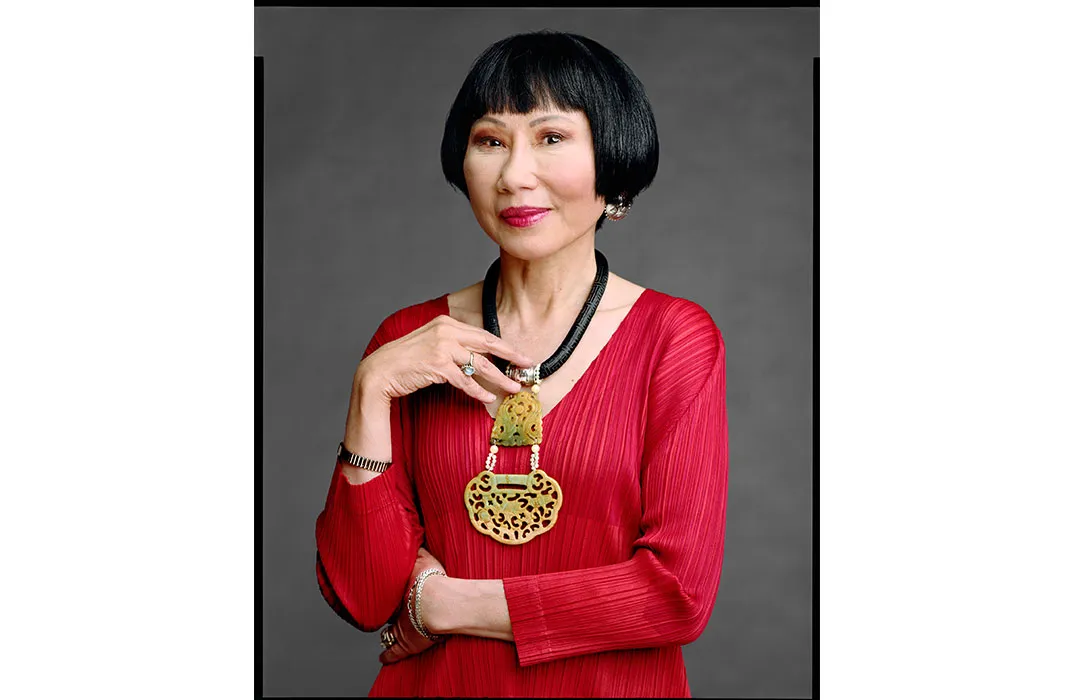

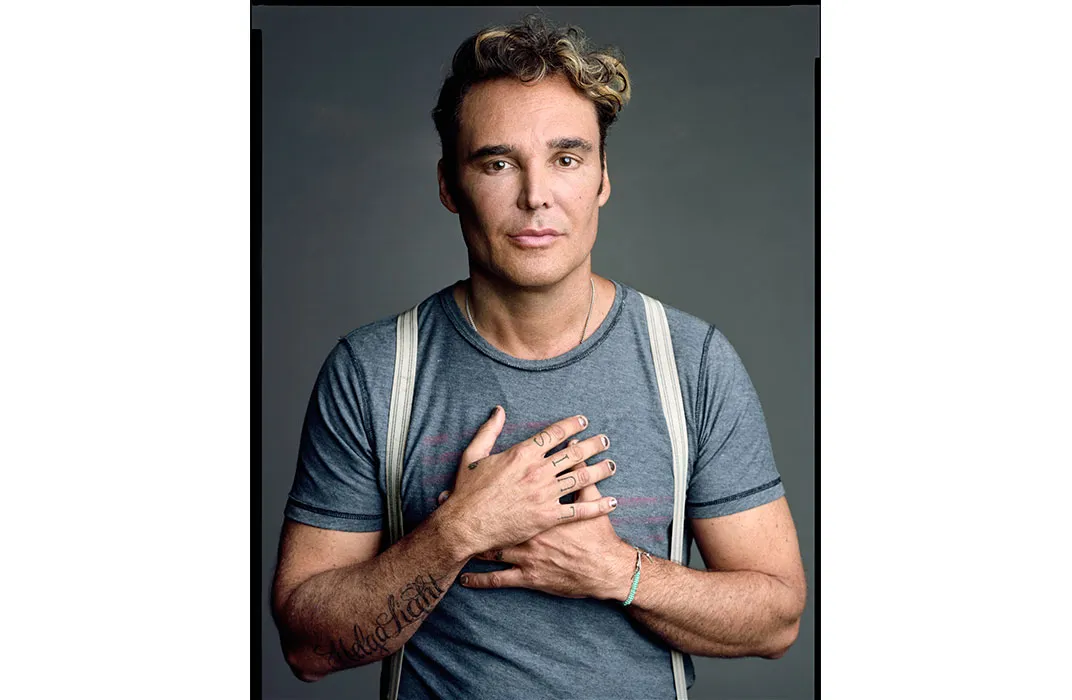

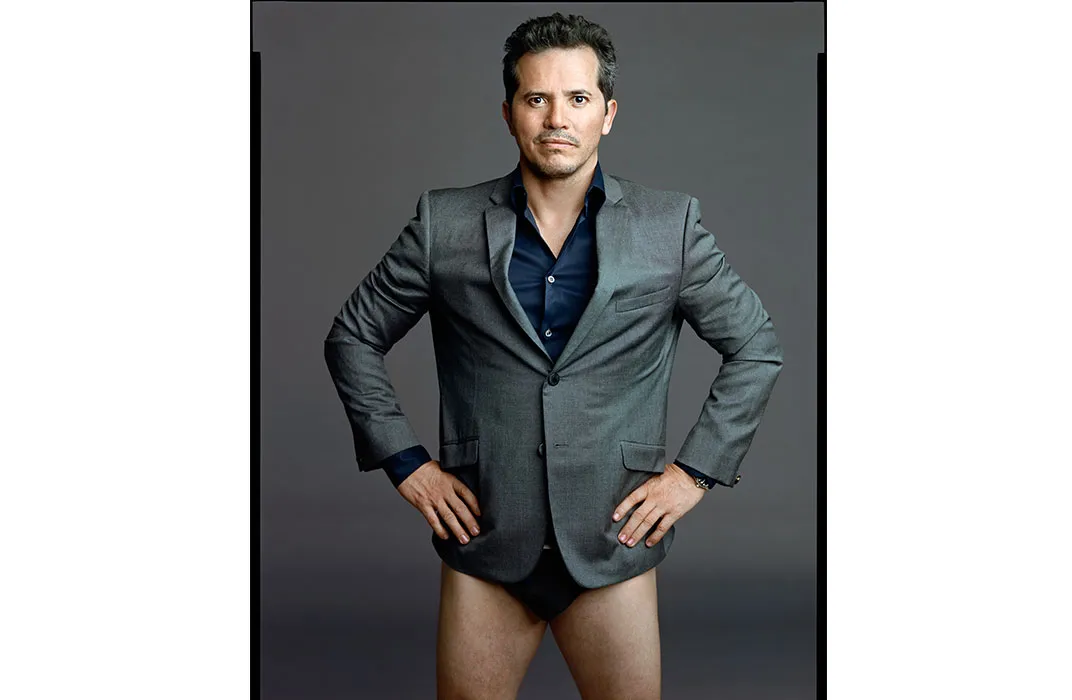

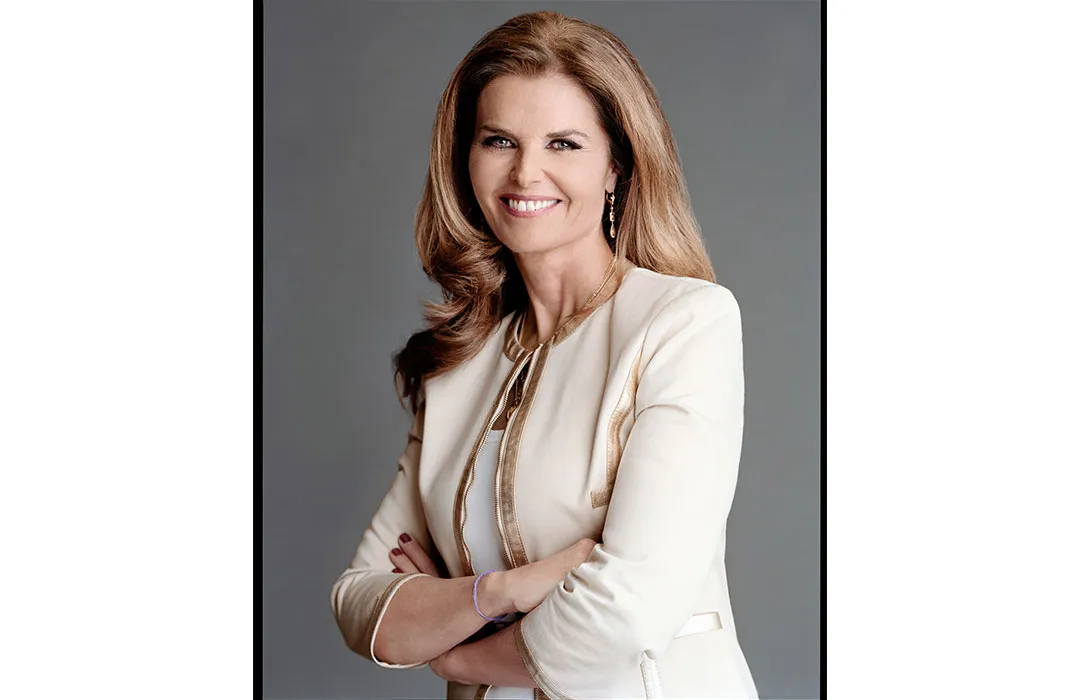

Subsequently, he selected 19 American figures (one born each year of the baby boom) to represent the issues that shaped that legacy, including environmental activist Erin Brokovitch, author Amy Tan, Vietnam Veteran Tim O’Brien, athlete Ronnie Lott, AIDS activist Peter Staley, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and IBM's CEO Virginia Rometty. Greenfield-Sanders told me in a phone interview that his Boomer selections were not always the most obvious characters, but that he “wanted to balance fame with sophistication” and to represent a wide range of diversity. Neither the exhibition of large format pigment prints, nor the accompanying PBS American Masters documentary “The Boomer List” follows a strict chronology from 1946 to 1964. Rather, the vast subject is organized by focusing on individual Boomers who tell stories embracing their entire generation.

In a panel discussion at the Newseum moderated by PBS Newshour journalist Jeffrey Brown, Greenfield-Sanders said it had been “a nightmare” to select his 19 Boomers. And yes, it is a lot to ask such a few to represent so many: there is Billy Joel, for example, but where is Bruce Springsteen? Baryshnikov? Bill Murray? Arianna Huffington? Tina Brown? The Boomers’ social subset is so vast that a list of one-Boomer-per-year seemed preferable to organizational chaos.

The 90-minute American Masters documentary on the Boomers featured interviews with each of the chosen. All have been activists in their various fields, and all have had an impact. Some were surprised to consider their “legacy,” as if that were some far-off notion. This is a generation, after all, that thinks of itself as “forever young,” even as some near 70. Most of all, what came across onscreen as well as in Greenfield-Sanders’ portraits was an unapologetic affirmation of the essential Boomer mantra—yes, it is still all about ME.

According to the U.S. Census, the Boomer generation numbers 76.4 million people or 29 percent of the U.S. population. It is still the vast majority of the work force and, as Millennials are discovering, not in a rush to gallop off into the sunset.

"TIME Covers the Sixties" will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery through August 9, 2015. “The Boomer List” will be at the Newseum through July 5, 2015.

The Boomer List

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/ca/3aca8203-edd6-4e50-b478-d5b65efb4a98/lott-finalforweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/79/62798774-90e6-48e9-94ad-12c1ea230875/ochoa_finalforweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/63/4063729b-03d0-40ee-ae55-464f662a790c/rometty_finalforweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)