Delivering the Mail Was Once One of the Riskiest Jobs in America

A new exhibition at the National Postal Museum honors the nation’s first airmail pilots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/51/4951c879-e0fa-4f73-96ad-659852bcc3a2/2c2_1_1918takeoff-02.jpg)

On May 15, 1918, as hundreds of thousands of American troops fought from the trenches of Western Europe, a small number of U.S. Army pilots took on a domestic mission. Though they worked in the skies above East Coast cities, far from the carnage of World War I, their task was life-threatening, and it was as crucial to the nation’s psyche as any conflict fought on foreign soil. While their peers carried bombs across the Atlantic, these men carried the mail.

On a gloomy Wednesday morning, thousands of spectators gathered in Washington, D.C., to witness what would be the world’s first regularly scheduled airmail service. As the crowd in Potomac Park buzzed with excitement, President Woodrow Wilson stood with the pilot, Second Lieutenant George Leroy Boyle. The two men chatted for a few minutes, Wilson in a three-piece suit and bowler hat, Boyle in his leather flying cap, a cigarette in his mouth. The president dropped a letter in Boyle’s sack, and the pilot took off for his journey from Washington to New York, with plans to stop in Philadelphia for delivery and refueling. The flight, however, never made it to the City of Brotherly Love.

With only a map laid across his lap to guide him on his northbound journey, Boyle turned southeast shortly after takeoff. Realizing his mistake, he landed in a soft field in Waldorf, Maryland, damaging his propeller. Officials from the United States Post Office Department, the predecessor to the United States Postal Service, drove the load of mail back to D.C., and unceremoniously put it on a train to New York. Two days later, after blowing a second chance to fly the mail north and making an emergency landing in Cape Charles, Virginia, Boyle’s time with the Post Office came to an inglorious end.

Boyle may not have been the Army’s best pilot, but his misadventures highlight just how bold of a decision it was to begin airmail service at a time when flight was still in its infancy. “There was a rather general feeling that aviation was not yet sufficiently advanced to maintain mail schedules by airplanes,” said Otto Praeger, the Second Assistant Postmaster General, in a 1938 interview. “Strangely enough, some well known aircraft manufacturers themselves doubted the advisability of embarking upon a regular airmail service, and a number of them came to Washington to urge me not to undertake the project.” But Praeger stayed the course, determined to make airmail “like the steamship and the railroad, a permanent transportation feature of the postal service.”

Unfortunately, indelibly changing the nature of mail delivery came with serious risk for the pilots involved. Of the roughly 230 men who flew mail for the Post Office Department between 1918 and 1927, 32 lost their lives in plane crashes. Six died during the first week of operation alone.

“They all understood the bargain they had made: risking their lives to get the mail where it needed to go,” says Nancy Pope, curator of the National Postal Museum’s new “Postmen of the Skies” exhibition, a commemoration of U.S. Air Mail’s 100th anniversary. “Businesses, government, banks, people—mail was how communication happened in America. This was not a universe where you’re sending a postcard to your grandma because she doesn’t like to text.”

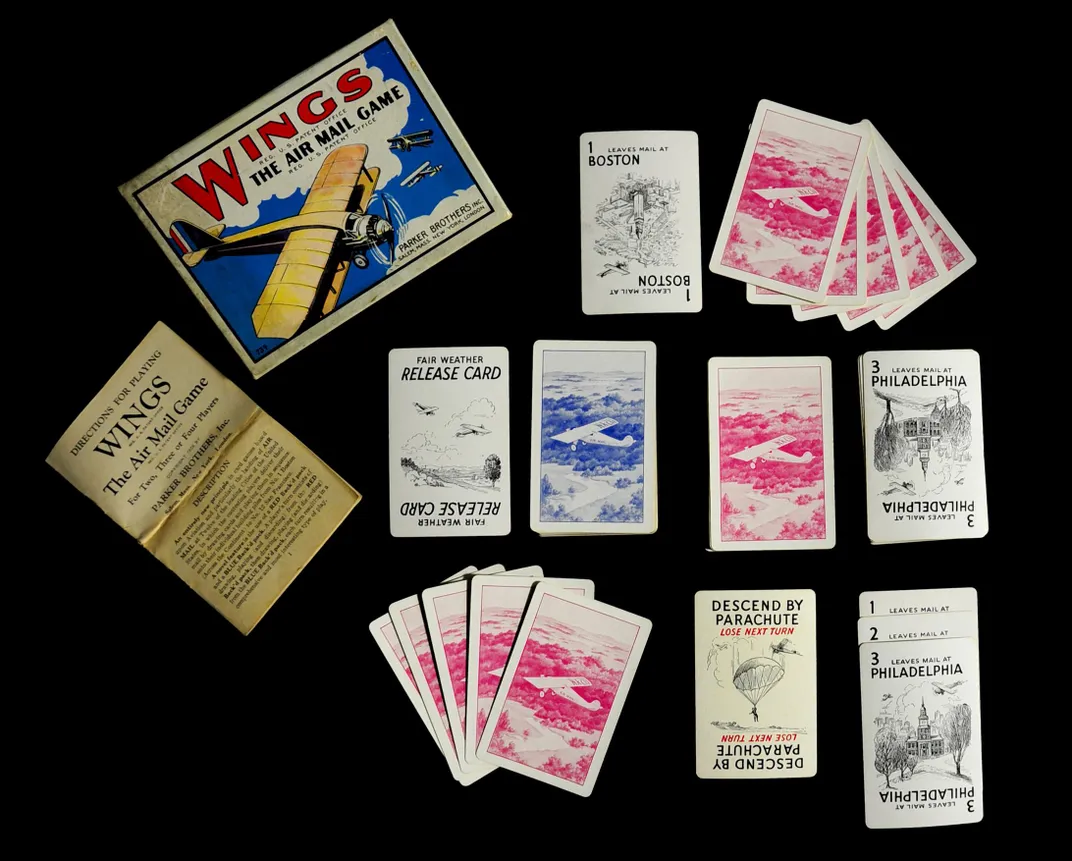

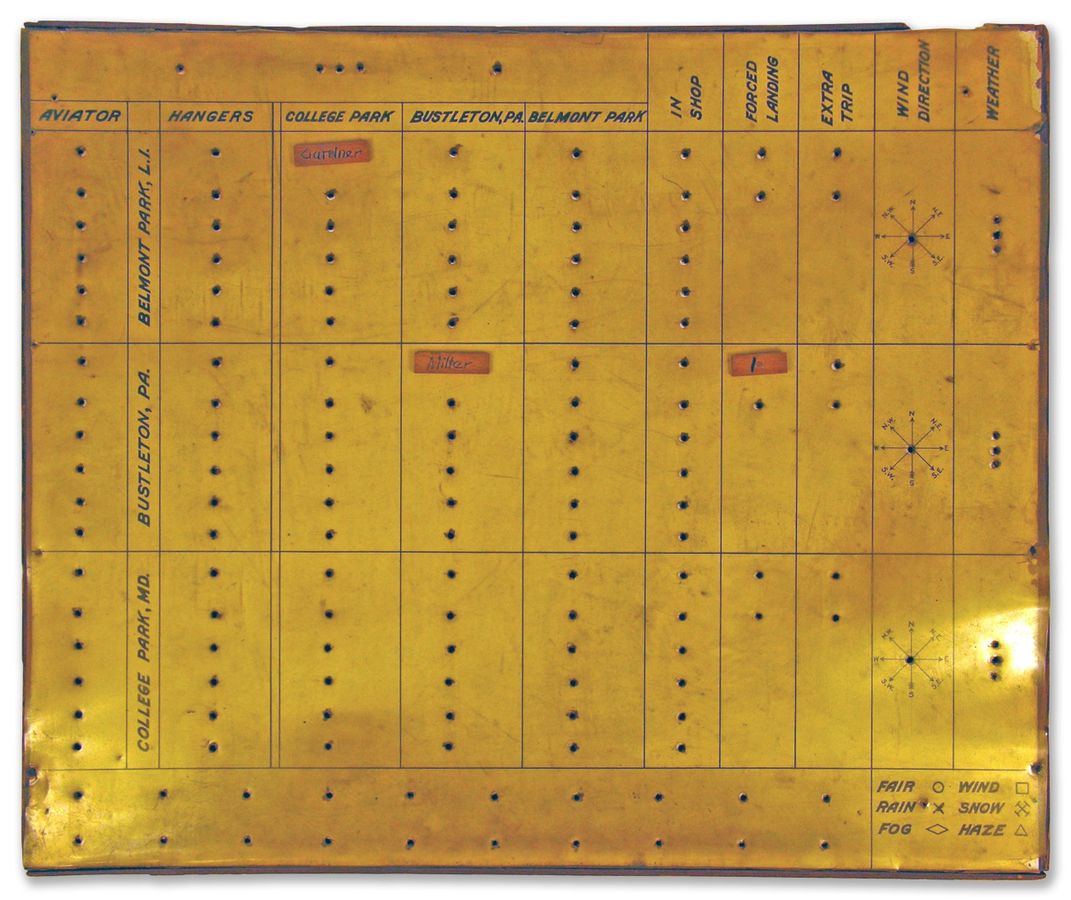

From cover stories in the Saturday Evening Post to Mickey Mouse cartoons and board games, the new airmail service captured the imagination of the American public. Recognizing this widespread enthusiasm, the Post Office Department released a special delivery stamp featuring a blue Curtiss JN-4 (Jenny) biplane inside a red frame. When 100 were accidentally printed upside down, the “Inverted Jenny” quickly became one of the most sought-after collector’s items in history. Today, a single Jenny can bring in more than $500,000. At the May 1 opening of “Postmen of the Skies,” authors Kellen Diamanti and Deborah Fisher released a book on the history of the Inverted Jenny, entitled Stamp of the Century, and the U.S. Postal Service unveiled a commemorative Forever Stamp featuring a similar blue-and-red aviation scene.

Everyone was talking about airmail, and it was the pilots who were the superstars of this early 20th-century cultural phenomenon. “These guys were the astronauts of their age,” says Pope. The Post Office received hundreds of applications, many from men who had no flying experience but were “eager to learn.”

They all wanted to become household names, following in the footsteps of the famous Jack Knight, the man who saved airmail.

Knight’s story began in the late winter of 1921. By then, the Post Office Department’s airplanes were going coast to coast, but with neither illuminated landing fields nor lights on the aircraft, the flights could only deliver mail during the day. Without advanced navigation systems, pilots had to rely on terrestrial features—mountains, rivers, and railroads—to guide their way. One would fly from Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, to Cleveland, for example, land, and put the mail on an overnight train to Chicago. The next day, another pilot would fly the mail to Iowa City or Des Moines, put it on another train, and so on, until it reached San Francisco. Congress was not impressed by the complicated relay, seeing the whole process as inefficient, and it threated to defund the service.

Knowing his cherished airmail may be in its final hour, Otto Praeger organized a well publicized demonstration in which teams would fly day and night to transport their precious cargo. On February 22, 1921, George Washington’s birthday, two planes left New York heading west, and two left San Francisco heading east. The westward-bound flights were grounded by heavy snow in Cleveland and Chicago. One of the eastward-bound pilots crashed and died taking off from Elko, Nevada. That left only Jack Knight, hobbled by a broken nose, bruises and the effects of a concussion he had sustained when his mail plane crashed into a snow-covered peak in Wyoming's Laramie Mountains a few days earlier.

Knight was supposed to fly only from North Platte, Nebraska, to Omaha, but when he arrived, a snowstorm was descending upon the Midwest and his relief pilot was nowhere to be found. He was left with a choice: give up, and accept Air Mail’s demise, or fly at night, in blizzard conditions, over territory that he had never even traveled during the day. Knight chose hazard—and glory—eventually touching down in Iowa City, where workers had lit barrels of gasoline to outline the landing field. By the time he refueled and was ready to continue east, it was dawn. He landed in Chicago to a barrage of reporters, and Congress soon voted to continue funding Air Mail.

Knight went on to have a decades-long career with United Airlines. America’s commercial aviation industry, in fact, owes its existence to airmail. In 1925, Congress authorized the Post Office Department to contract out its service flights to burgeoning passenger airlines, and by the end of 1927, all airmail was carried under contract. It wasn’t until the mid-1930s, though, that private airlines—TWA, Pan Am, Delta, Varney (which became United), and others—could attract enough passengers to offset the cost of operating. These companies made it through their first decade thanks to airmail revenue and the former Post Office pilots that they employed.

The Post Office also offered to provide the commercial airlines with the cold-weather gear that their pilots had worn in flight. When one pilot, Eddie Allen, heard about this, he wrote a letter to his old boss asking for his equipment: “I would very much like to have these things which I used in carrying the mail over the Rockies for the Air Mail Service, as a personal memento,—an expression of appreciation of unusual services, for I gave the very best I had in me to the Air Mail Service.”

"Postman of the Skies: Celebrating 100 Years of Airmail Service" is on view through May 27, 2019, at the Smithsonian's National Postal Museum, located at 2 Massachusetts Avenue N.E. in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AdamGreenScreenSq.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AdamGreenScreenSq.jpg)