When the Painting Is Also Poetry

A sublime new show honors the Chinese tradition of the ‘Three Perfections’—poetry, painting and calligraphy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/68/ee687824-9528-4057-9b5c-6f6b668e7793/painting-with-words-2314001web.jpg)

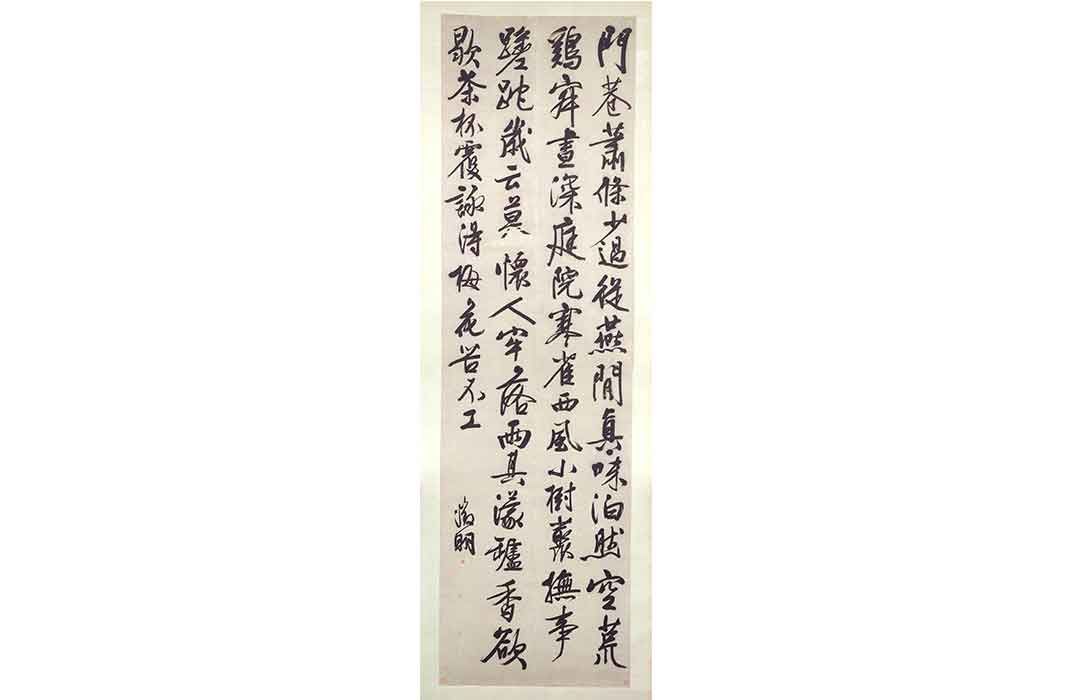

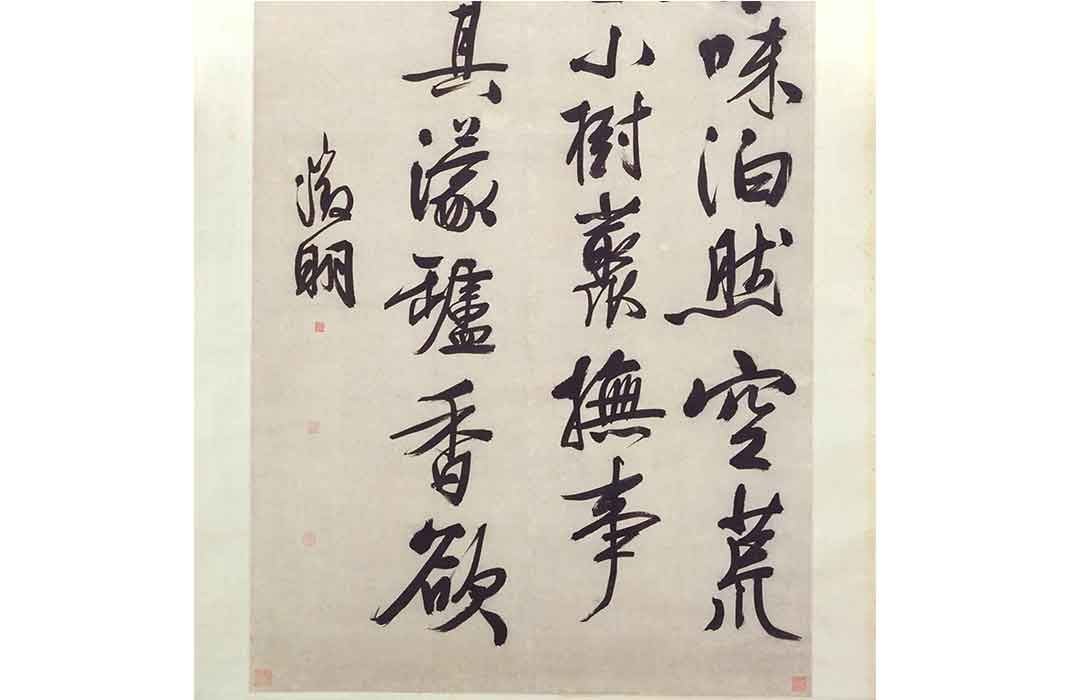

Two enormous hanging scrolls of Chinese calligraphy are unrolled dramatically at the entrance of the new exhibition “Painting with Words: Gentleman Artists of the Ming Dynasty,” on view at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. In the gallery next door is a third one.

These three floor-to-ceiling showstoppers are as striking and contemporary looking as a grease crayon work by Richard Serra. But they are poems.

One, in agitated brushstrokes, is a melancholic reflection, At Leisure in My Studio at Year’s End, from ca. 1540. More than 10 feet high and nearly 5 feet wide, it reads (in partial translation):

“The lane at my gate is desolate and drear, few are those who come to call. . . . My friends are scattered few and far apart and the rain just drizzles on.”

Stephen D. Allee, the museum’s associate curator for Chinese painting and calligraphy, who organized the show, notes: “We know of only five scrolls of this heroic size by the artist Wen Zhengming [1470-1559] and this is the only known example with a personal poem.”

Wen left a prestigious job in the Ming Imperial Court after only eight years because he was unhappy with the ruthless politics of the day. For the next 32 years, he lived the life of a gentleman scholar in retirement—reading, painting and composing poetry. Wen composed the poem “At Leisure” when he was 30, in 1500, but the artwork on imposing view was created when he was 70. By then he was a famous calligrapher, presumably commissioned by a private client to make a copy of his poem (he probably needed the money, Allee says).

The artwork At Leisure is among 45 scrolls and album leaves in the show that were created between 1464 and 1622 by Wu School artists based in the canal-studded city of Suzhou (still called “the Venice of the East”).

The Wu School takes its name from the thriving kingdom that once ruled the region. Wu School artists excelled at music and drama but were particularly admired for their mastery of poetry, painting and calligraphy.

“These complementary art forms, known collectively in China as the ‘Three Perfections,’ were considered the ultimate modes of literati expression,” explains Allee.

The Three Perfections come together in each landscape.

“The paintings all have inscribed poems on them,” Allee says. “The inscription is fundamental to understanding what the work of art is about.”

If, for example, four artists went on a trip together, one might paint a landscape and the others respond to it with poems. “There is an interrelationship between the image and the poem,” Allee says. “The inscription tells you the history of the trip.”

He continues: “Poetry was the primary vehicle of polite social exchange then. The poems inspire, accompany and respond to the paintings and calligraphy.”

Many of the Wu School painters and calligraphers knew one another. One, the painter, poet and calligrapher Shen Zhou, for example, was a close friend of another painter, Liu Jue, who married Shen’s older sister. The two artists went on sightseeing trips together.

“The more you understand the personal, professional and stylistic relationships among these artists, the more you understand the individual pieces,” Allee says. “Most of these paintings were done by friends for friends (or family members), so the responses are quite personal.”

The poems would make the landscapes come alive, at least to any Chinese viewer.

“Poetry is a much better vehicle for the expression of emotion than painting or calligraphy, both of which draw on ideas,” Allee says.

Sometimes, poems were added much, much later by outsiders.

One landscape by Shen Zhou, Expecting Visitors, depicts a robed gentleman standing in the doorway of a modest lakeside studio, his servant by his side holding a scroll, waiting to greet guests. One visitor has just moored his boat and is walking across a footbridge. Another is arriving by boat, carrying a box of food. The peach trees are in bloom, to signify spring. They are set to spend a nice afternoon together admiring the scroll.

Shen Zhou dedicated the painting to Hua Fang (1407 -1477), a contemporary from a prominent, wealthy clan who rescued some land north of Suzhou after a devastating flood and eased the tax burden on the local population. The man in the studio probably represents Hua as a scholar gentleman, awaiting friends in his secluded garden, which refers to his refined taste and noble character.

The inscriptions were added by no less a personage than the emperor—300 years later. Allee tells us the Qianlong emperor (1735-1796) so admired this landscape that he added a calligraphic frontispiece and four poetic inscriptions. Presumably the emperor identified with the philanthropist.

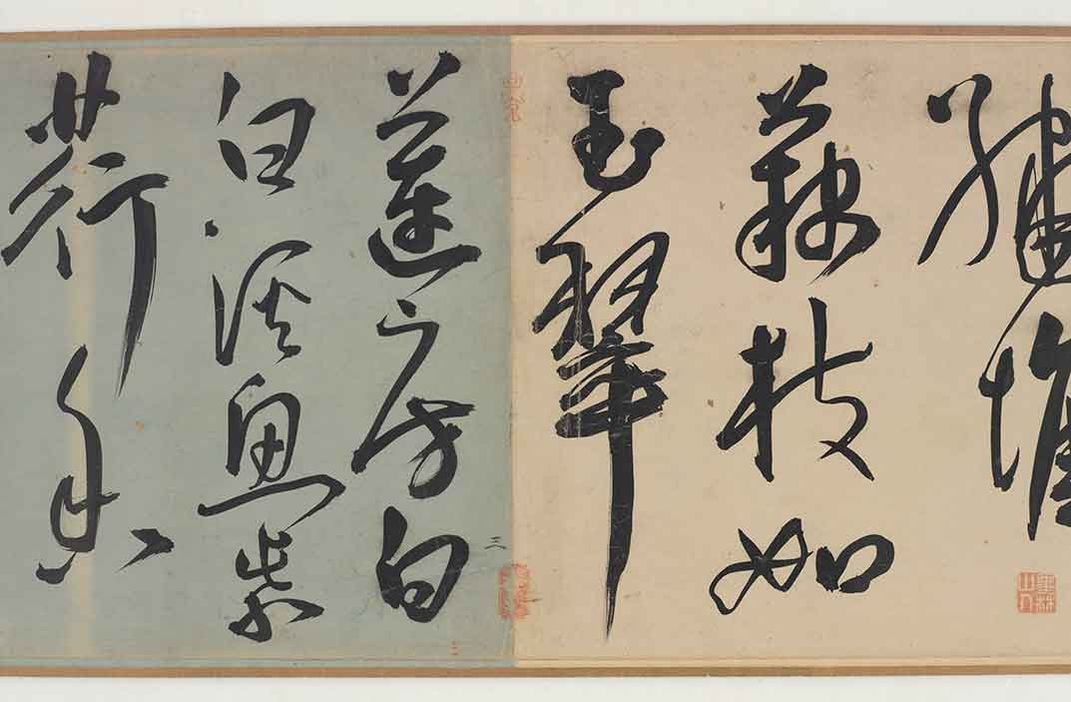

Calligraphy scrolls were often created at social gatherings. Allee points to a long hand scroll in a horizontal case. The calligraphy gets looser as you read it from right to left (this is how the Chinese write). He says friends would get together for long evenings of art—and drinking. Inevitably, the calligraphy loosens up as the night wears on.

Allee explains how calligraphers worked: A servant or “writing boy” would stand at one end of a long table, a second at the other end. As the calligrapher worked, one servant would roll up the calligraphy-covered paper as the other, on the far end, unrolled the blank paper. The calligrapher never had to move.

“The timing was very important between the master and his helpers,” Allee says. “The calligrapher is focusing on the ink and brushes. His motions come from the elbow and shoulder, not the wrist. There is a kind of physical dimension to it, so he would not lose the fluidity. The writing boys watched the master, so when he leaned over to reload the brush, they could scroll the paper.”

In the exhibition, 30 landscapes artists are represented. Allee displays the works in a digestible way, by artist, recipient and the occasion for making the work of art. The poems are translated above in red lettering. The wall labels describe what is happening in the scene, its symbolism and the specific art techniques and styles employed (many of them conscious references to masters of the earlier Tang and Song dynasties).

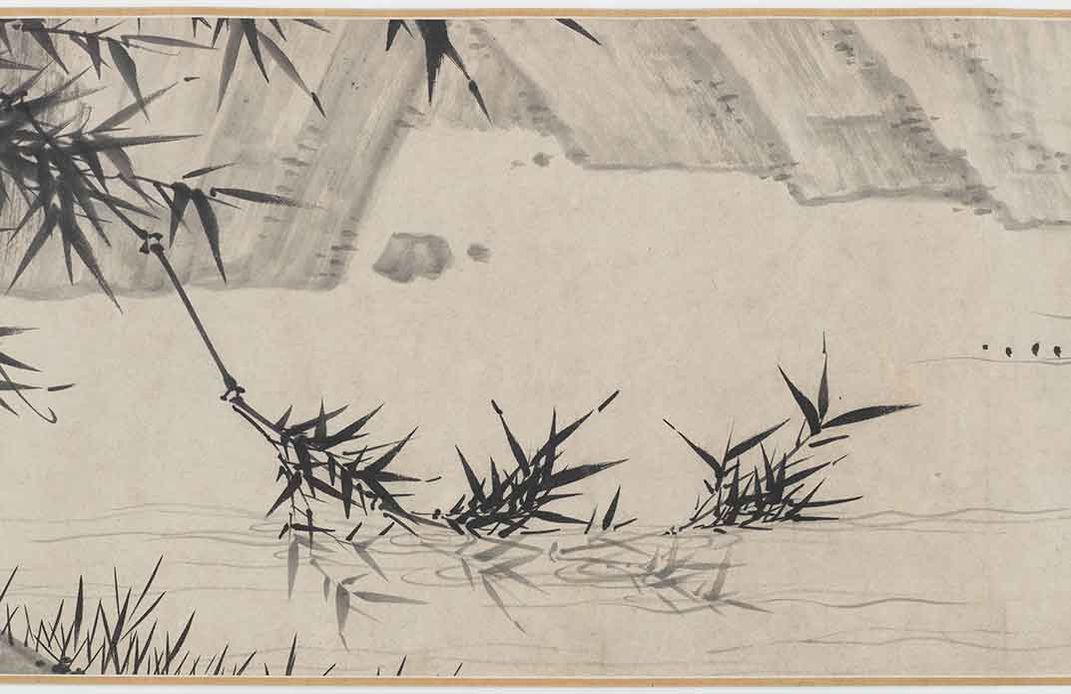

One vignette of “Xiao-Xiang River After Rain” by Xia Chang (1388-1470) particularly stands out: A low-lying branch of bamboo on a riverbank dips into the water, but only for a few inches, before it re-emerges on the surface. Submerged leaves are pale gray; the others coal black.

Not only is it brilliantly painted but it is also true to life. I saw the same thing last week while hiking in the valley of Bryce Canyon in Utah.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/wendy_new-1.jpeg)