When A Race Car Becomes a Work of Art

Salvatore Scarpitta’s automative wonder goes on view at the Hirshhorn

Born in New York City to a Sicilian father and a Polish mother, he grows up in Hollywood, flees to Europe and makes his reputation in Italy. Only then does he return. What more could we ask of any modern American traveler?

Salvatore Scarpitta (1919-2007) may be the most underrated great in modern American art. He was a friend of Rauschenberg and de Kooning, Oldenburg and Johns, a giant among giants who shared a studio in Rome with Cy Twombly and bar stools in Greenwich Village with the likes of Lichtenstein and Stella.

Scarpitta first became famous for his wrapped and bandaged “relief” canvases of the 1950s, which turned painting inside out by making the linen sculptural. Woven and torqued and slit and lacquered, torn like battle dressings or wrapped like swaddling clothes, they are as vibrant and essential today as they were revolutionary then. He was subsequently claimed by every school of aesthetics from the Readymades to Arte Povera to Movimento d’Arte Concreta, but he refused to be limited by language or style or politics or category. He was his own man (as the Hirshhorn’s “Salvatore Scarpitta: Traveler,” opening July 17, attests). The sleds are proof.

The sleds began in the 1970s, made of whatever he gathered from the New York sidewalks. Odds and ends bound tight with gut and rawhide, they were wrapped like mummies. As primitive as they are bleak, the sleds are about what we all carry, what we all drag through life. Each as hopeless as a lost expedition. But Scarpitta may be most famous—and least understood—for his cars.

For critics and curators, “race car” is a grade-school palindrome. To a driver, a mechanic, a fan, an artist, a race car is a set of passions and appetites and sculptural specifications.

Auto racing began the day they built the second car, and more than a century later the rules and proportions of function and form are as fixed in the eye as anything dug from Athens or Carthage. That shape. Sal Scarpitta was obsessed with an aesthetic so well suited to its purpose.

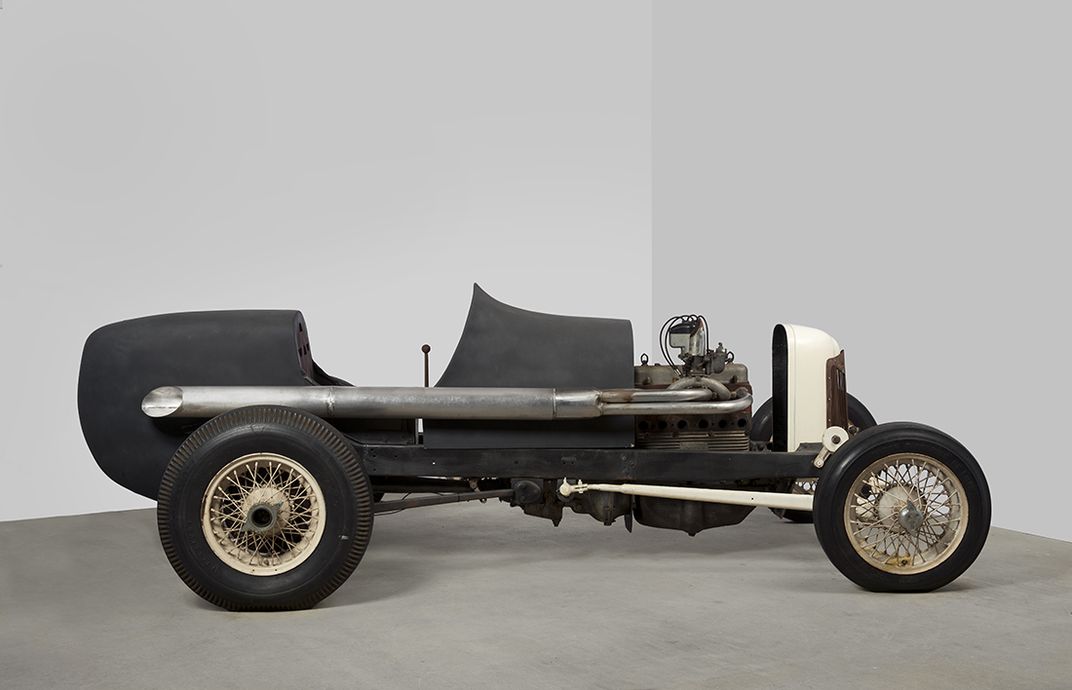

He built his first art car, the Rajo Jack, in the early 1960s. Inspired by the racers he’d seen as a child in California, it felt like an elegy: unfinished but already wrung out. Like his Sal Cragar (1969)—unpainted, pitted with rust, motionless—it is almost funereal. The two cars express as much about entropy and longing and the end of history as they do about velocity.

But the heart of racing is dynamism. Life. Death. Motion. Tension. Sensation. Scarpitta was so drawn to it all that he started his own race team in 1985. Where the lithe popgun racers of postwar Europe were underpowered and nimble, dirt-track sprint cars like his Trevis Car (Sal Gambler Special, 1985) are perfectly American, blunt instruments of horsepower and recklessness turning circles in places like Mechanicsburg and Terre Haute and Merced.

There’s something primordial about running a sprint car on a dirt track, something elemental. Geologic. Mud flying everywhere, and that tectonic rumble like the earth coming apart. The crowd roaring behind the fence, covered in dust. Every lap sideways, right foot to the floor, a hundred miles an hour. Engine noise like a horn on the morning of the Last Day. Easy to spin, easier to flip, as unstable as a 600-horsepower grocery cart. A Friday-night scandal of risk and spectacle, of departure and return.

Where others see chaos, racers and artists see the possibility of order. Go back to the chariot—then all the way back to the wheel and fire—to understand the desire to be cut loose at last from our physical limits.

The absolute beauty of an American racer is readymade in its lines, its power and its noise. In its uselessness. It carries nothing but ambition. Like all art it produces only metaphor and sensation. Contradiction. It sets out as fast as it can, all sound and fury, racing away from wherever it started—even as it turns inexorably, helplessly again for home.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)