When Was the First Inaugural Ball?

Nothing says there’s a new president in town more than the dance party they throw

Ever since George Washington took the oath of office as the nation’s first president, fellow countrymen have turned out on the dance floor to celebrate. But the inaugural ball wasn’t always a thing. The first one was held in 1809, for James Madison, but the balls have come and gone, depending on the times and the incoming president. One thing has held true: in general, the ball, or balls, have been vehicles for well-heeled and ardent supporters to express their joy for the new office-holder.

The ball—an old-fashioned word that conjures up images of 19th-century cotillions—persists because of “our illusions and our fantasy,” says Carl Sferrazza Anthony, a historian with the Canton, Ohio-based National First Ladies Library. It’s a democratic version of a christening, he says. The ball is the “jewel in the crown of these series of events” that makes up the inauguration of a president, says Anthony. “It’s like premiere night for a new era in America.”

Elizabeth Goldsmith, professor emerita at Florida State University, says it helps bring closure to the whole celebratory day. “What better way than to dance?” says Goldsmith, an expert on inaugural festivities. The ball also is a long-practiced tradition, and tradition is something that dies hard in inaugural history, says Goldsmith. The organizers and presidents “hold on to these traditions long past when the general public does,” she says, noting that John F. Kennedy wore a top hat to his inaugural (despite apocryphal stories saying otherwise)—many years after it had ceased being a fashionable style.

The ball is just one more disconnect between modern times and America’s love for tradition, says Goldsmith.

There are “official” and “unofficial” balls. Official ones are sponsored by the Presidential Inaugural Committee, and guarantee ticketholders that the president and his wife will show up. The bill for these balls is covered by the committee, which raises money from supporters—taxpayers do not pay a cent for the celebrations. Historically—whether for a Republican or a Democrat—the supporters have been friends of the president—often big donors—and corporations looking to curry favor.

Donald Trump’s Presidential Inaugural Committee has raised a reported $90 to $100 million to fund its multiday celebration—a record-breaking figure that far exceeds the $53 million spent by Barack Obama’s committee on his first inaugural in 2009. But, in a surprise, Trump—who’s not known for eschewing the lavish and bold—is holding only three official balls. “That’s a radical reduction in the number of balls,” at least in the modern era, says Anthony.

Obama had ten official balls in 2009, including one where he danced with wife Michelle as Beyonce crooned the Etta James mainstay “At Last.” By his second in 2013, there were only two official balls, but the performers were top-drawer, including Broadway star Jennifer Hudson, and Alicia Keys, Brad Paisley, John Legend, Katy Perry, Marc Anthony, Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder.

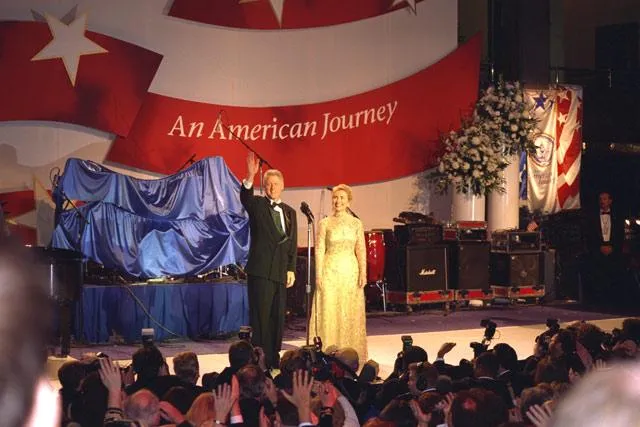

George W. Bush had eight official balls for his first inaugural, and nine for the second. Bill Clinton may have held the record number of official balls: 14 for his 1997 inaugural.

The first President George—Washington, that is—didn’t get an official ball. Instead, supporters invited him to stop by a regularly held dance in New York—where he and his wife were living at the time, said Anthony. George and Martha danced a minuet, captured in a drawing displayed on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar.

No real celebration was held in honor of an incoming president again until 1809, when a group of James Madison’s friends quickly threw together a party, which is now considered the first inaugural ball, according to Anthony. Most of the 400 people who paid $4 apiece to attend were members of the Washington, D.C. elite—those who had the money or the connections to get a ticket to the event, held at Long’s Hotel.

The Madison ball helped to establish public expectations for a certain kind of celebration, says Anthony. It also may have been in the first of a long line of overhyped parties for a new president. John Quincy Adams remarked in his diary that “the crowd was excessive, the heat oppressive, and the entertainment bad.”

Attendees at inaugural balls are expected to be in the most elegant of formal wear. Crowds run from the hundreds to the thousands at a single event. Ballgoers are likely to encounter a cash bar, long lines for that bar and for checking or retrieving a coat, and paltry food offerings. The ballgoer—who may have paid $50 (the price of a Trump ball ticket) to several hundred dollars—will likely only get a quick glimpse of the new Commander-in-Chief. In 2001, George and Laura Bush danced an estimated 29 to 56 seconds at each of the balls they attended.

Many balls have gone wrong. In 1829, Andrew Jackson’s more ardent supporters—fueled by whiskey-laced punch and dressed in hickory nut necklaces and carrying hickory sticks to honor their man, who was known as Old Hickory—ran amok at an inauguration day open house at the White House, breaking up furniture and shocking denizens of Washington society. The party has been cited as the reason why balls were henceforward held in other venues, says Anthony.

But that was nothing compared to what was visited upon the guests at another war hero’s inaugural ball. It was a brutally cold day in March 1873 when Ulysses S. Grant was sworn in. His ball was held in a temporary wooden building that wasn’t designed to withstand the below-zero wind chills that day. As ballgoers—swaddled in their overcoats—attempted to dance, dead canaries rained down. The birds had been hung in cages from the rafters as joyful decorations.

A bird of another feather interrupted Richard Nixon’s second inaugural, held in 1973 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History). A live chicken escaped from the “American Farm” exhibit, taking refuge in a $1,000 guest box. Fittingly, Smithsonian’s Secretary at the time, S. Dillon Ripley, captured the poor creature and the party went on.

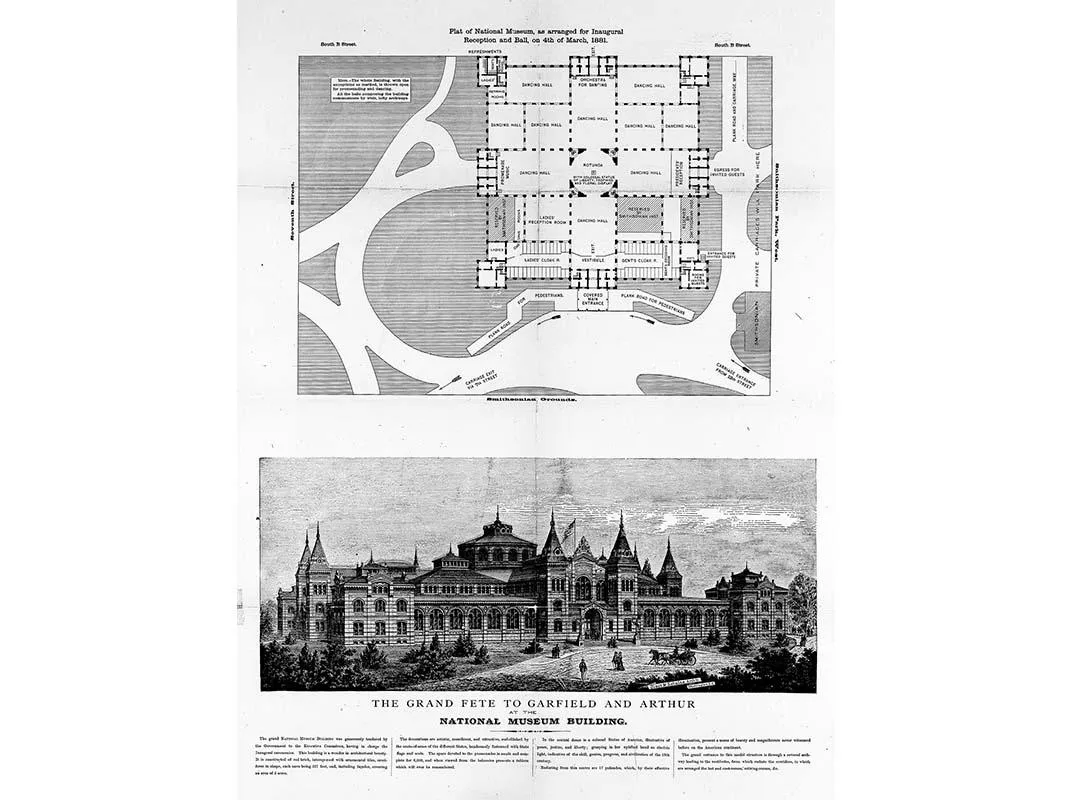

The Smithsonian’s museums have frequently hosted inaugural balls, starting with the first party that set the template for the inaugural ball as we’ve come to know it—James Garfield’s, in 1881, held at the newly completed Arts and Industries building, says Anthony. Some 7,000 people danced and ate in the elaborately decorated hall.

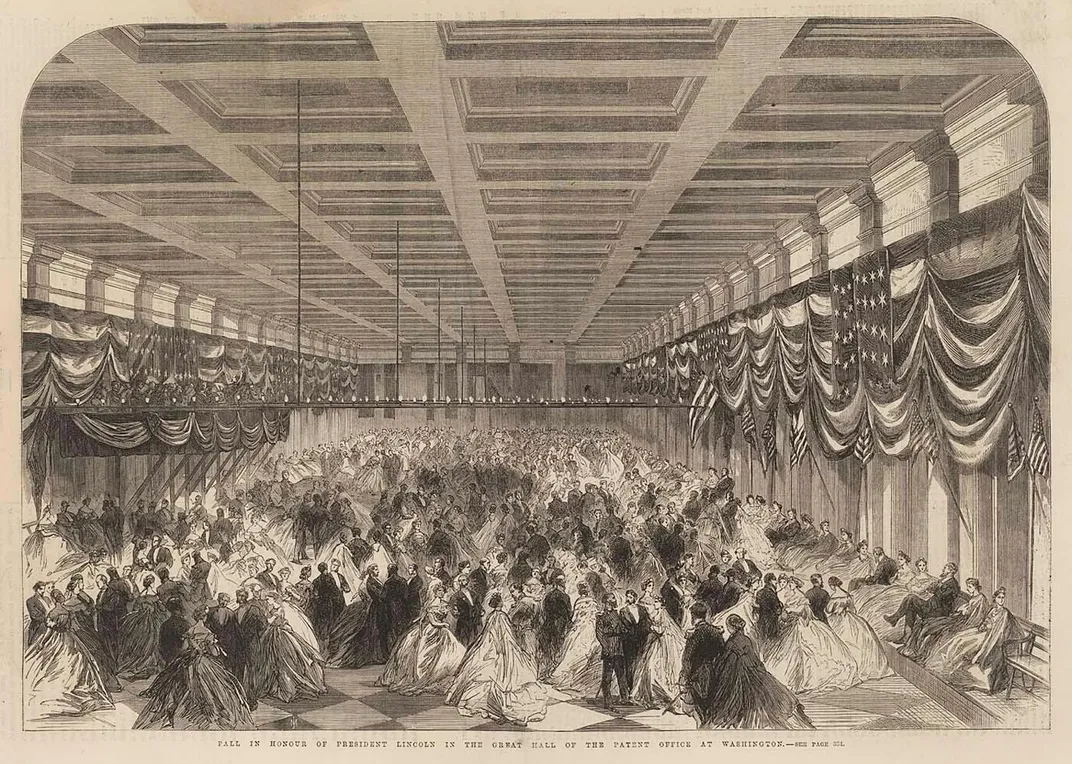

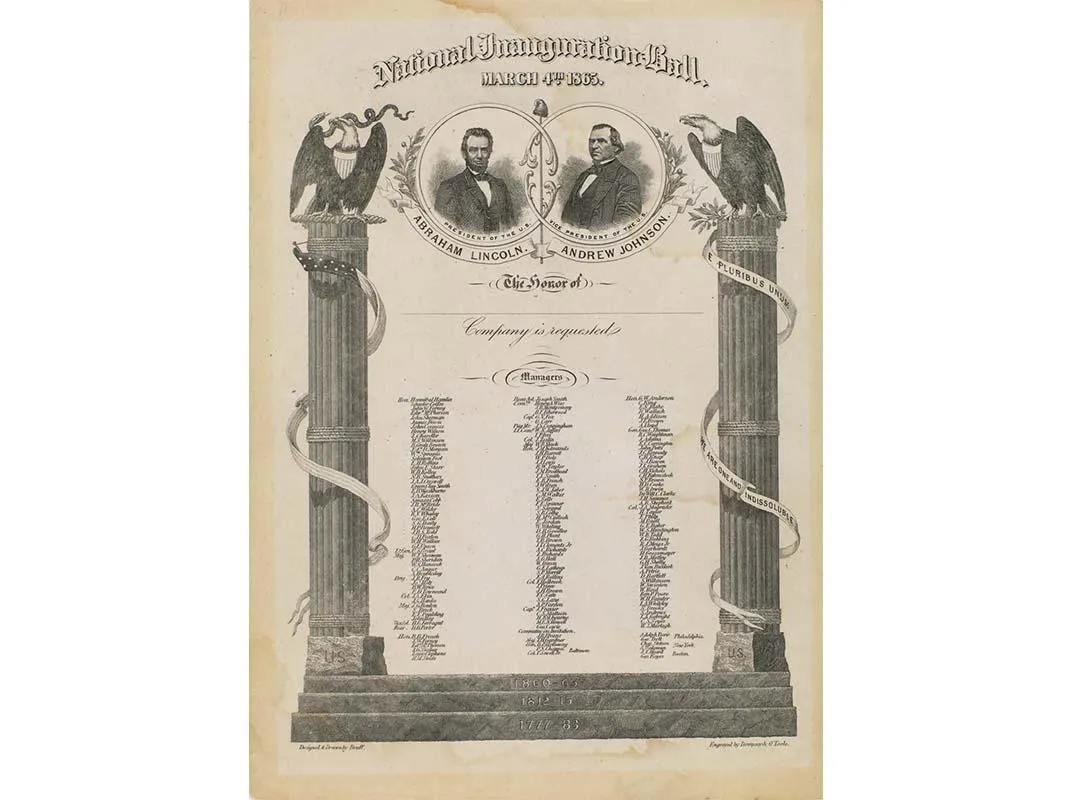

Other Smithsonian locations have been the site of inaugural balls including the National Air and Space Museum (Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, twice) and the U.S. Patent Office building, now home of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, which was the site of Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural in March 1865.

The inauguration of McKinley was probably the apex of 19th century artifice, he says. It (and many subsequent balls) was held at Washington, D.C.’s vast Pension Building (now the National Building Museum). The president, his family and friends sat in a box in a mezzanine above the 116- by 316-foot Great Hall’s colossal Corinthian columns. They looked down on the crowds, lending the ball an almost monarchical sensibility, says Anthony.

That tradition—of the elegant, almost royal ball—continued until Woodrow Wilson came into office in 1913. A devout Presbyterian, Wilson did not approve of dancing, and specifically looked askance at the dances of the times, including the Turkey Trot, the Grizzly Bear and the Hunny Bug. He cancelled all the inaugural festivities, including the ball.

Times were so bad in 1921 that Warren Harding’s supporters urged him not to have a celebration. But his friends—which included the society maven Evalyn Walsh McLean, owner of the Hope Diamond—wanted a big party. In the end, McClean and her husband paid for the ball, says Anthony. That ushered in an era of charity balls, which lasted through the Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt administrations.

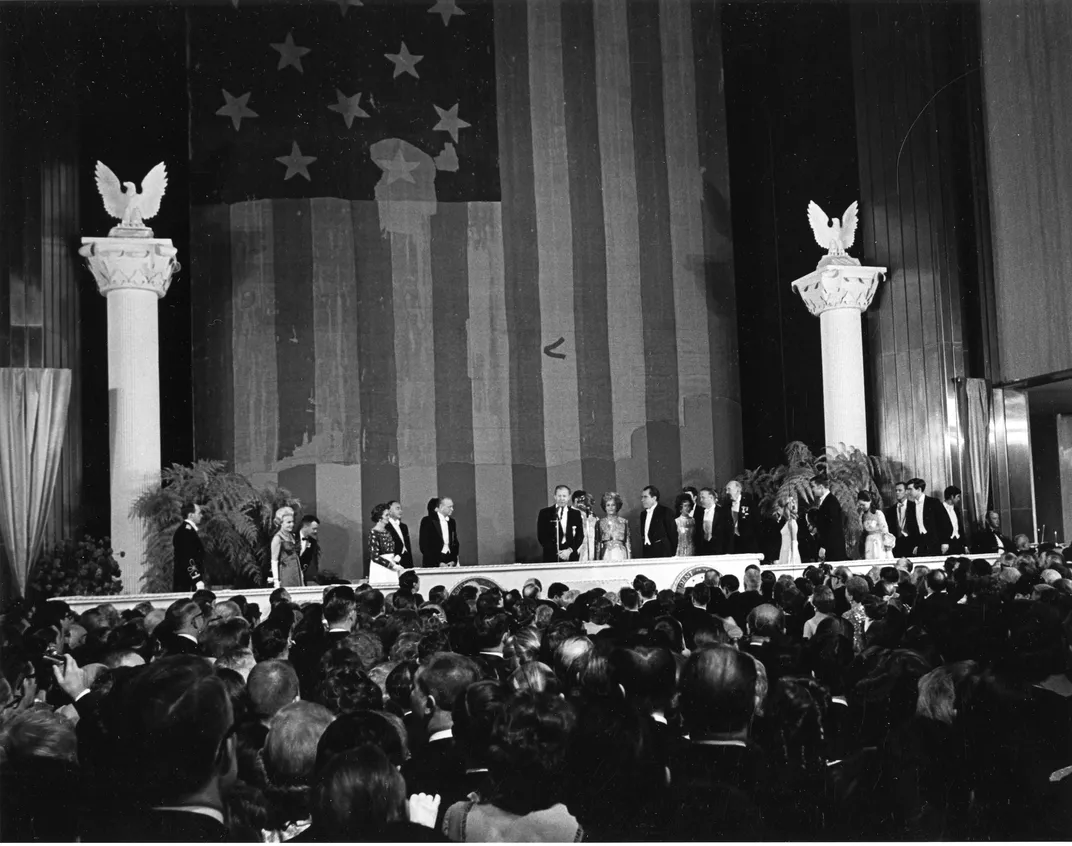

Harry Truman raised the bar with his second inaugural ball in 1949, says Anthony. The inauguration itself was the most expensive and elaborate in history at that time, with congressional Republicans having previously allocated a record budget of $80,000 in anticipation of a victory by their candidate, Thomas Dewey, according to the Harry S. Truman Library. Some $29,000 of that went to the ball, held at the National Armory in Washington.

The Reagans—who were practically Hollywood royalty—were roundly criticized for the expense and lavishness of their inaugural in 1981. Eight of the 9 official balls were only open to those who were invited, and they were held at elegant locations like the Kennedy Center and the Pension building, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. The Reagans were accustomed to glitz and wanted to provide a counterpoint to Jimmy Carter, who, instead of having inaugural balls, held concerts at seven Smithsonian museums. Despite the dismay about the Reagans, their parties were not any more over-the-top than the Truman celebration, says Anthony.

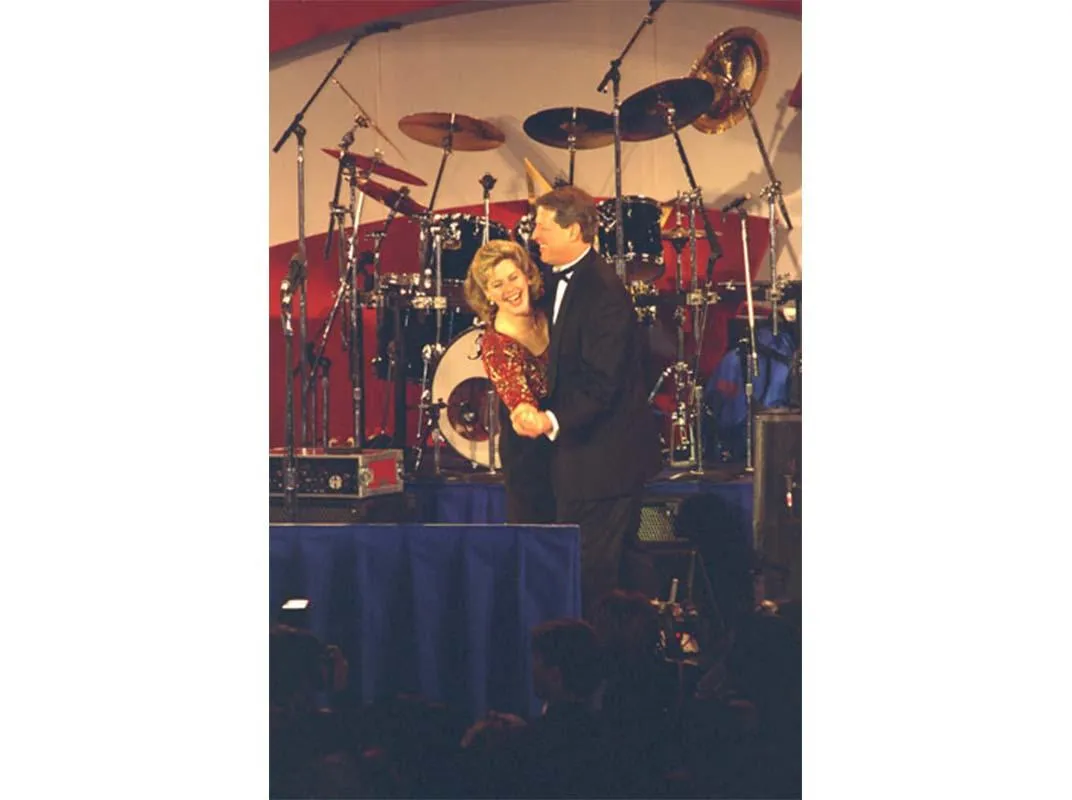

Nixon began the practice that’s now customary—making an appearance on a ball stage with the First Lady and the Vice President and his spouse, perhaps saying some words of thanks, and dancing for a bit, while also posing for photographs. “It gave the public the next morning the visual that they were expecting,” Anthony says.

The American public may not be sure what kind of visual to expect from the Trump festivities. Some things will be quite traditional—he plans to attend the three balls with his wife, Melania. And she will donate her gown to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, as has become the custom. It will be added to the First Ladies Collection, which has featured dozens of inaugural gowns in exhibitions over the last 100 years.

When asked to venture a guess as to how the Trump balls might be different, Anthony demurred, noting that the incoming president has been full of surprises. “I just don’t know,” he says.

It's your turn to Ask Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/cc/09cc4c92-5b6a-4bdf-855e-d8d96bdef34d/sia-sia2009-0247-000001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)