When the Yankees Got the Larger-Than-Life Babe Ruth

It was a fateful December a century ago, when the Red Sox-Yankees trade launched a dynasty; a Smithsonian curator reflects on the legendary home-run hitter

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/b9/20b9f9f9-acf9-4497-a404-8a44b2bbb715/gettyimages-80902348.jpg)

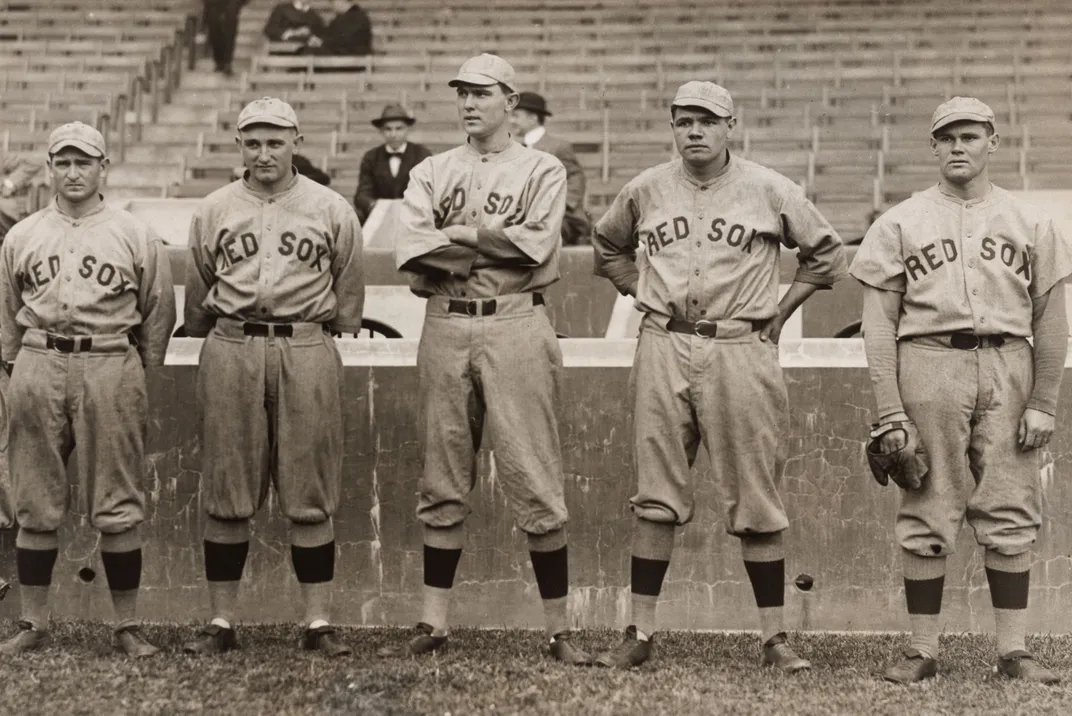

Once, while pursuing a pop-up foul ball, the great baseball legend Babe Ruth ran into a cement wall, knocking himself out cold. Five minutes later, when he awoke after being splashed with a bucket of ice water, he didn’t leave the field to recover from the sidelines; instead, he finished the game, going 3 for 3. And then, incredibly, he played the second game of the double-header. Ruth disliked bowing to unexpected events, but that was his fate when he was traded a century ago, by the Boston Red Sox on December 26, 1919, despite setting a major league home run record that season.

For anyone who has lost a job and felt a loss of control, there is some consolation in knowing that even the indomitable Babe Ruth was traded away after helping the Red Sox win three World Series. He donned the uniform of the then-struggling New York Yankees and changed baseball history by helping to create a wildly successful Yankee dynasty that has since captured 27 World Series championships over the past century.

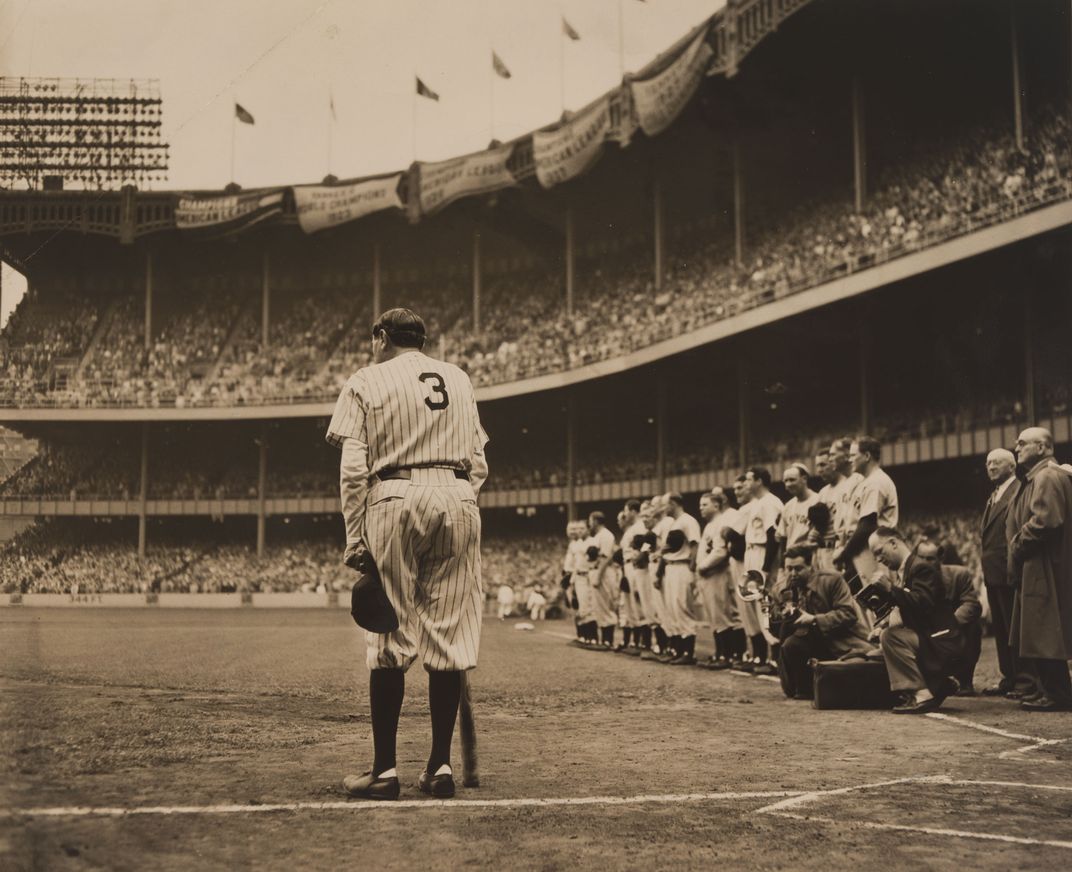

For that reason, the first Yankee stadium, which opened in 1923, became known as “The House that Ruth Built.” And for years, the “Curse of the Bambino” cast a dark shadow over the Boston Red Sox, who with Ruth’s help won World Series victories in 1915, 1916 and 1918, but battled for more than 80 years before finally claiming triumph in 2004. The trade also set off a lasting rivalry between the Yankees and the Red Sox.

Here’s how it all went down. In 1919, the owner of the Red Sox, Harry Frazee, was in debt. He needed cash for his other ventures, namely his Broadway shows, such as his short-lived play, My Lady Friends, which lasted just 214 performances in 1919 and 1920. He traded Ruth for $25,000 in cash and three $25,000 promissory notes. Thus, the man who was arguably the best player in baseball was exiled for a promise of $100,000, or about $1.5 million in today’s dollars. In addition, Frazee received a $300,000 loan. But money wasn’t Frazee’s sole motive for the trade: Ruth was strong-willed, hard to manage, and dissatisfied with his salary of $10,000 per season.

Baseball insiders would come to know the heat of his volcanic temper and watch his astonishing appetites for food, drink, women and brawling. He was a “glutton, drunkard, hell-raiser, but beloved by all,” wrote biographer Robert W. Creamer. Often, when Ruth was not expected to bat during the next inning, he walked out of the ballpark and downed a beer and a hotdog. Drawn in by his star power, many women flocked toward the homely and married slugger. Other team members joked about sharing a room with Ruth’s suitcase while he spent the evening with women.

While the trade “wasn’t the best thing” for the Red Sox and caused anguish among the team’s supporters, says curator Eric Jentsch at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History: “Fans need to understand that owning a sports team is also a business and that these people have various interests outside the running of the team.”

To Frazee, Jentsch says, the trade made sense.

While playing for the Red Sox, Ruth was an impressive pitcher. During much of the 1918 season, he took the mound every fourth game, but then played in the outfield on the other days. As one of the American League’s best left-handed pitchers, he finished 13 scoreless innings in the 1916 World Series—a record that still stands.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/a3/55a3e550-40a1-4595-a437-9c316decb8a9/npg_93_80-ruth_gehrig-r.jpg)

Of course, Ruth was a powerful hitter. In his last season with the Red Sox, he smashed 29 home runs, setting a major league record for the season. A year later, the new Yankee, after a slow first month with no homers, quickly began slugging away. He beat his own high watermark, blasting 54 home runs in 1920, averaging .376 and claiming 137 RBIs. The following year, he broke his home-run record again, reaching 59. He led the Yankees to capture seven American League pennants in his first 13 seasons. For that same period, the Red Sox won none. Ruth played a key role in Yankee World Series triumphs in 1923, 1927, 1928 and 1932. Surprisingly fast for a man who weighed 215 pounds, he tripled 136 times and ten times during his career, he stole home. Primarily, Ruth played as a Yankee outfielder and pitched occasionally.

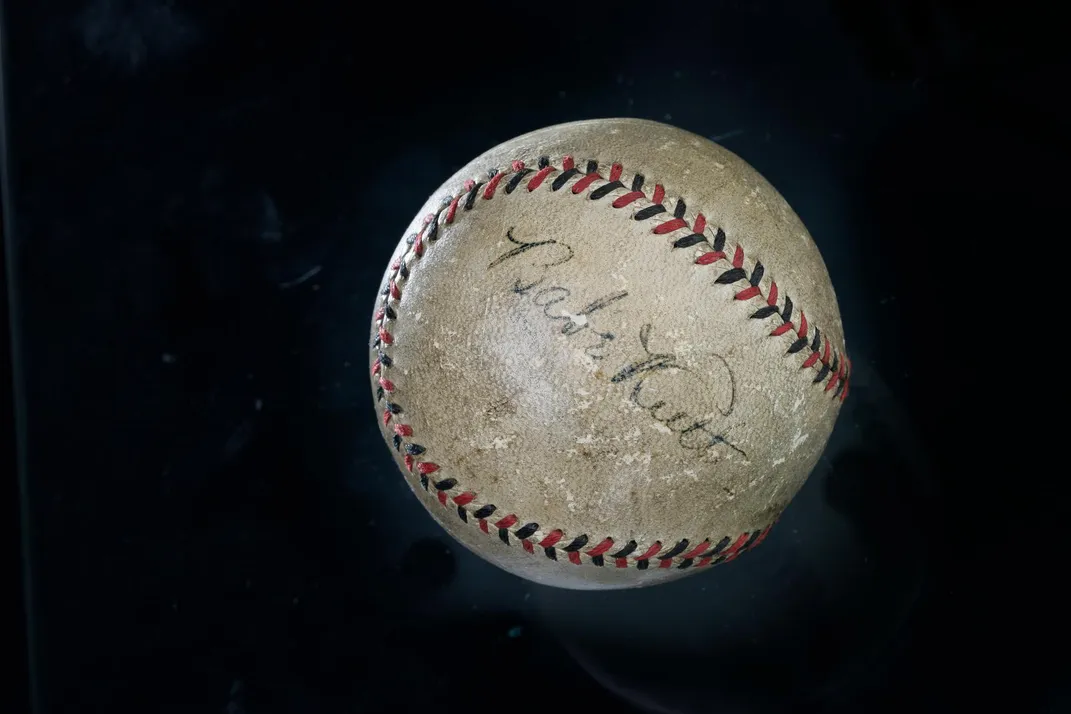

During the 12 seasons between 1920 and 1931, he topped the American League in slugging 11 times; home runs, ten times; walks, nine times; on-base percentage, eight times; and runs scored, seven times. His batting average exceeded .350 in eight seasons and reached .370 in six. The National Museum of American History holds a baseball autographed by Ruth, which was featured in the book The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects. The ball was donated by a man whose father asked Ruth to autograph it for him during a Ruth visit to Scranton, Pennsylvania, in the 1920s. The Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery has an extensive collection of the slugger's images (including several in this article) and exhibited many of them in 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/a7/4da7303b-5fd6-4bee-b1be-747ba7453afa/npg_89_99-ruth-r.jpg)

Ruth’s best-remembered home run came in the 1932 World Series against the Chicago Cubs. In a game played at Wrigley Field, the score was tied 4-4, with the Yankees leading the series with three wins. Ruth came to bat in the fifth inning. He was greeted by a chorus of boos from Cubs fans and players. He watched two called strikes go by. And then he pointed. Some thought he was scolding the Cubs’ bench or threatening to knock down the Cubs pitcher, but afterward, many more believed he was pointing toward centerfield, where he hit a soaring home run.

A film discovered in 1992 does seem to indicate that he pointed to centerfield, but the veracity of the “called shot” legend remains subject to controversy.

“Whether he called it or not is not really the point,” says Jentsch. “The point is we still talk about it as if it happened. . . . If something like that was to have happened, it would have to be Babe Ruth, right?” It became part of American mythology.

“He has become more than a man,” adds Jentsch. The story itself and its longevity show “how we can use entertainment to create these special moments of hoping and giving. It shows a connection between fans and the players that may or may not even exist.” Jentsch compares the “called shot” to the often-told tale about George Washington and the cherry tree: Children hear the story and learn at the same time that it is not true, but the myth still survives as part of American culture.

At his salary peak, Ruth earned $70,000 as a player in 1927, when he set a season’s home run record of 60 that would stand for 34 years. On top of his salary, he earned $20,000 from product endorsements. That gave him a total income of what would roughly amount to $1.3 million in 2019 dollars. (The highest paid athlete in the world today is Lionel Messi of the Futbol Club Barcelona, who cleared $127 million in 2019. His salary constituted $92 million of that income.)

George Herman Ruth Jr, who picked up his “Babe” nickname in the Baltimore Orioles minor league system, was more than a baseball player: He was a cultural phenomenon. At the time of his stardom, New York City had more than 15 English-language newspapers, and newsstand articles about Ruth were hot commodities. In the same period, fans in the stadium began to change. The introduction of Sunday games invited women and children to partake in America’s favorite pastime. Neighboring Italian communities gave Ruth the nickname “Bambino” to go along with the “Sultan of Swat.”

Outside the ballpark, Ruth also made news. After being jettisoned by his parents who declared that he was “incorrigible” at the age of 7, he grew up in an orphanage, and later he showed a special empathy for children. He seldom bothered to learn the names of his teammates, calling everyone “kid,” but he would tirelessly autograph baseballs for youngsters eager to meet a legend. During his Red Sox years, he often hosted day-long picnics and ballgames for busloads of orphans at his Sudbury farm, winning admiration—despite all his other hijinks—as a fun-loving philanthropist.

“If Babe Ruth had not existed, it would have been impossible to invent him,” one observer told HBO for a 1998 documentary. “He was the Fourth of July and a brass band and New Year’s Eve all rolled into one.” In at least one heat wave, he slipped a cabbage leaf under his cap to avoid broiling in the outfield, and when he was out on the town, he wore mink coats. “Babe Ruth is not just a legend now, he was a legend in his own time,” baseball Hall of Fame curator Tom Schieber says. One of his Yankee jerseys sold for $5.64 million in 2019, setting a record for the sale of any piece of sports memorabilia.

Eventually, Ruth’s athletic talents faded, and he left baseball in 1935 with a career record of 714 home runs, which would remain unbroken until Hank Aaron slammed his 715th as a player for the Atlanta Braves in 1974. (Barry Bonds subsequently surpassed Aaron’s mark.) Ruth had hoped to become a manager, but his volatility made that impossible. “How can he manage other men when he can’t even manage himself?” said Yankees General Manager Ed Barrow.

Ruth died in 1948 of cancer; he was only 53 years old, but his legend stands a century later. Because of his unique personality and his athletic achievements, Jentsch believes, he “was adopted as part of the new media landscape, becoming a towering figure.” His place in the Jazz Age elevated him and made him someone we still discuss today, he says, while many of Ruth’s contemporaries are forgotten.

A small piece of the House that Ruth Built is currently on display at the American History Museum. It is a ticket booth from the original Yankee Stadium. For years, the Yankees shared the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants. After Ruth’s first season, when the Yankees drew 350,000 more fans than the Giants, the Yankees were asked to leave.

On opening day at the new Yankee Stadium, Ruth hit the ballpark’s first home run. They were playing the Red Sox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)